Amoskeag Manufacturing Company facts for kids

The renovated space of Amoskeag Mills, c. 2006

|

|

| Industry | Textile Rail transport |

|---|---|

| Fate | Declared bankruptcy |

| Predecessor | Amoskeag Cotton & Woolen Manufacturing Company |

| Successor | Amoskeag Company |

| Founded | 1810 |

| Founder | Benjamin Prichard |

| Defunct | 1935 |

| Headquarters | , |

| Products | Denim, locomotives |

|

Number of employees

|

17,000 |

| Divisions | Amoskeag Locomotive Works |

The Amoskeag Manufacturing Company was a huge company that made textiles (like cloth). It started the city of Manchester, New Hampshire, in the United States.

This company began small in a wild area. But during the 1800s, it grew to be the biggest cotton cloth factory in the world!

At its best, Amoskeag had 17,000 workers. It also had about 30 buildings. However, in the early 1900s, the company couldn't keep up with new changes. Many textile factories moved to the Southern U.S. Because of this, Amoskeag went out of business in 1935.

Many years later, the old factory buildings were fixed up. Today, they are used for offices and restaurants. You can also find software companies, college classes, art studios, apartments, and even a museum there.

Contents

History of Amoskeag

How It Started

In May 1807, a man named Samuel Blodgett finished building a canal and lock system. This was next to the Merrimack River in a town called Derryfield. His work helped boats travel between Concord and Nashua. This opened up the area for new businesses. It also connected the region to a trade network leading to Boston.

Blodgett had a big dream. He wanted to create a "Manchester of America." This would be a place powered by water. It would be a textile center, just like Manchester, England. He had visited Manchester, England, which was a leader in the Industrial Revolution. He suggested changing Derryfield's name to Manchester in 1810.

That same year, Benjamin Prichard and others started the Amoskeag Cotton & Woolen Manufacturing Company. A year before, he and three brothers (Ephraim, David, and Robert Stevens) bought land. They also bought rights to use the water power. This was on the west side of the Merrimack River. They built a mill there.

They bought used machines from Samuel Slater to spin cotton. But these machines didn't work well. In 1811, new machines were built. These machines spun cotton into yarn. Factory workers were paid with this yarn. Weaving cloth was done by local women at home. They earned a few cents for each yard they wove. A good weaver could make 10 to 12 yards (about 9 to 11 meters) per day.

But the mill didn't make money. After September 1815, "little or nothing was done." In 1822, Olney Robinson bought the company. He borrowed money and equipment from Samuel Slater. But Robinson was not good at running the business. So, it went to the people he owed money to.

Slater then sold most of the company in 1825. Dr. Oliver Dean and others from Massachusetts bought it. In April 1826, Dr. Dean moved to the area. He watched over the building of the new Bell Mill. It was named for the bell on its roof that called workers. The Island Mill was also built on an island in the Merrimack River.

They also built homes for workers and stores. This created the factory village of Amoskeag. The three mills did very well. They were known for their excellent "sheetings, shirtings and tickings" (types of fabric). Their success attracted more investors. With a lot of money (1 million dollars), the business became the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company on July 1, 1831. Offices were set up in Boston. The main boss usually worked there. A manager in Manchester oversaw the workers and mills.

Building Manchester, New Hampshire

Engineers decided that the east side of the Merrimack River was best. This is where the company planned to build many mills and canals. They also planned a whole mill town. So, in 1835, they bought most of the land on the east side. Eventually, they owned 15,000 acres (about 60 square kilometers) there. They also bought all nearby water rights. This stopped other companies from using the water power.

The company built a foundry and a machine shop. These places made and fixed the mill machines. In 1838, the city of Manchester was planned and started. In 1839, Stark Mill No. 1 was finished. This mill was part of Amoskeag. It had 8,000 spindles (parts of spinning machines). Six blocks of homes for employees were also built.

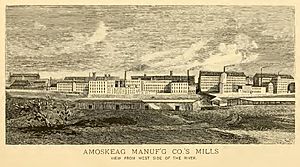

Throughout its history, Amoskeag's engineers designed all the factory buildings. This gave the whole complex a similar look. The buildings were made of warm red brick. This brick came from the company's own brickyard nearby. Towers with bells and stairwells made the factories look nice. Workshops were long and narrow with many windows. This helped them use natural light.

The Concord Railroad (later Boston & Maine Railroad) came to Manchester in 1842. Train cars brought raw materials, like cotton from the southern states. They then carried finished fabrics to markets across the country. One famous customer was Levi Strauss. His riveted blue jeans were made with cloth from the Amoskeag Mills.

Manchester became a city in 1846. It was meant to be a perfect factory city. Lowell, Massachusetts, a city thirty miles downriver, had been a model for this. William Amory, a company leader, and Ezekiel A. Straw, the first Amoskeag manager, helped design Manchester. It had wide streets and squares for public walks. It also had nice schools, churches, hospitals, fire stations, and a library.

Row houses (called corporations) were built. These were rented to workers with families. People sometimes waited years for a spot. Fancy houses were built for the company's top leaders. Parks gave employees fresh air and places to relax. Amoskeag Mills even gave 20 acres to create Valley Cemetery. The city's main street, Elm Street, was on a ridge. It was set back from the noisy mills. T. Jefferson Coolidge managed the money from 1876 to 1898. He made the company very profitable.

The company's leaders watched over almost everything in the company town. This included the workers' habits. Women workers were especially watched at work and at home. This was part of the Lowell System. At first, many workers came from nearby farms. But as more workers were needed, people were encouraged to move from Canada. Many came from Quebec, where farming was difficult. Other workers came from Greece, Germany, Sweden, and Poland. Each group often lived in its own neighborhood.

The company worried about workers forming unions. This was after the 1912 Bread and Roses Strike in Lawrence, Massachusetts. So, Amoskeag tried to stop unions. They promoted "Americanization" of workers. They also built Textile Field (now Gill Stadium) in 1913.

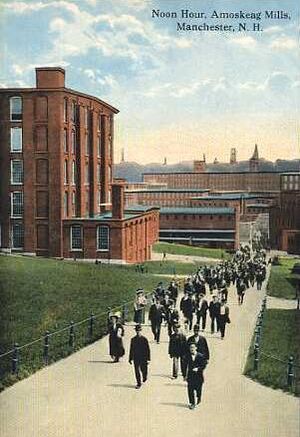

Child labor was common. Lewis Hine took famous photos of child workers at Amoskeag in 1909. Injuries and even deaths were not rare in the mills. When the bells rang at the end of the day, thousands of workers left the factories.

The Amoskeag Locomotive Works built locomotives (train engines) and fire engines. During the Civil War, cotton from the South was hard to get. So, the company's foundry made over 27,000 muskets (guns). It also made 6,892 Lindner carbines (another type of gun). The company also made sewing machines and, of course, textile machines.

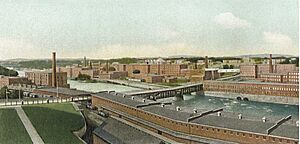

After the war, the country quickly industrialized again. Manchester became an even bigger textile center than its English namesake. Company engineers built more factories. They lined both sides of the Merrimack River. Mill No. 11 was the world's largest cotton mill. It was 900 feet (274 meters) long and 103 feet (31 meters) wide. It had 4,000 looms (weaving machines).

Gingham, flannel, and ticking were special products. But many other cotton and wool fabrics were also made. The noise from thousands of looms was very loud. Workers had to shout or lip-read to talk. Amoskeag was at its peak during World War I. It supplied the government with military goods. It had up to 17,000 workers in 74 textile departments. Its 30 mills wove 50 miles (80 kilometers) of cloth every hour. During the war, workers got more pay. Their work week also became shorter, from 54 to 48 hours.

Amoskeag in 1911

These facts are from a postcard made in 1911.

Facts about the Company:

- Number of looms: 24,200

- Number of spindles: 662,000

- Length of cotton and wool cloth woven each year: 237,000,000 yards (about 216 million meters)

- Number of bags woven each year: 1,500,000

- Number of water wheels (turbines): 30

- Power from water wheels: 16,290 horsepower (12,147 kW)

- Number of boilers (for steam): 185

- Power from boilers: 27,750 horsepower

- Number of steam engines: 12

- Power from steam engines: 15,100 horsepower (11,260 kW)

- Number of steam turbines: 5

- Power from turbines: 26,678 horsepower (19,908 kW)

- Number of electric generators: 14

- Power from generators: 41,175 horsepower (30,704 kW)

- Number of electric motors: 583

- Power of motors: 27,702 horsepower (20,657 kW)

- Oil used each year: 75,000 US gallons (about 283,900 liters)

Size of the Company:

- Total floor space in buildings: 5,844,340 square feet (543,000 square meters)

- Total land area: 137 acres (0.55 square kilometers)

Wages Paid: (Money paid to workers each year at the end of 10-year periods)

- 1831: $36,298

- 1840: $74,239

- 1850: $487,005

- 1860: $633,680

- 1870: $1,107,428

- 1880: $1,604,322

- 1890: $2,435,481

- 1900: $2,772,611

- 1910: $6,176,353

- 1911: $6,370,089

The total money paid in wages from 1831 to 1911 was $114,753,340.

Why the Company Declined

After World War I ended in 1918, the country's economy slowed down. In the early 1920s, fewer people bought Amoskeag products. Some mills stopped working for days, weeks, or even months. Without steady work or pay, workers felt less loyal to their employer. This loyalty had kept Manchester a city without many strikes.

Then, Parker Straw, a company manager, announced a pay cut. Starting February 13, 1922, all workers would get 20% less pay. Their work hours would also increase from 48 to 54 hours per week. The United Textile Workers of America told workers to strike. They did, and the whole city's economy suffered.

Even after Amoskeag brought back the old pay in August, workers kept striking. They wanted to go back to a 48-hour week. They also wanted to make sure strike leaders wouldn't be punished. After nine months, workers had to go back to work. They didn't get all their demands. But they did get a promise that the state government would think about a 48-hour work week law. However, this law was not passed. Amoskeag technically won the strike. But it was a victory that cost them a lot.

The strike made Amoskeag lose workers' loyalty. It also lost customers. This happened when new types of energy like electricity were replacing water power. Cotton could now be processed where it grew. This saved money on shipping to New England. Amoskeag's old machines made it hard to compete. Labor costs were higher in the North than in the South. The South had new factories and machines. New Hampshire also had a tax on supplies like coal and cotton. To try and stay competitive, Amoskeag made a mistake. They added more mills and machines. They hoped this would lower costs. But the textile industry already had too many factories.

A New Company Structure

In 1925, the company's money manager, Frederic C. Dumaine, made a big decision. He decided to split the company into two parts. He took the money Amoskeag Manufacturing Company had saved over the years. He put it into a new company called the Amoskeag Company. This new company was a holding company. This protected money for the owners of the holding company. But it meant the mills didn't get money to update their machines. This made it harder for them to survive tough times.

When the Great Depression started soon after, things got worse. The company tried to increase hours and cut pay again. This especially affected women, who were most of the workers. Violent strikes in 1933 and 1934 happened. The New Hampshire State Militia had to get involved. When the picketing stopped, some angry workers damaged machines and products. The struggling company closed mills one by one. Many employees lost their jobs when there were few other jobs available.

Bankruptcy and Closure

On Christmas Eve in 1935, the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company suddenly closed. It then filed for bankruptcy. A bad flood the next year ended any hope of it starting up again. A judge ordered that the huge factory complex be sold off. By 1937, half the buildings were used by other businesses. These businesses were part of Amoskeag Industries. This new group was started by local business people in 1936.

Lewis Hine Child Labor Photos

These are photos of children working at the Amoskeag Mills. They were taken by Lewis Hine in May 1909.

- Child labor at the Amoskeag Mills (May 1909)

The Mills Today

An inventor named Dean Kamen helped bring the Amoskeag mills back to life. He started buying and fixing up the mill buildings in the 1980s. Now, the old mills have offices, restaurants, and software companies. They also have college branches, art studios, and a museum. The Millyard Museum is located there.

The SEE Science Center has a huge Lego model of the Millyard. It has about 8,000 minifigures and five million bricks! It was built between October 2004 and November 2006. The Manchester Historic Association helped with research. They also gave the center an award for the project in 2006.