Lewis Hine facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Lewis Hine

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Lewis Wickes Hine

September 26, 1874 Oshkosh, Wisconsin, U.S.

|

| Died | November 3, 1940 (aged 66) |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | University of Chicago, Columbia University, New York University |

| Known for | Social reform |

| Movement | Documentary; social realism |

| Patron(s) | Russell Sage Foundation National Child Labor Committee Works Projects Administration |

Lewis Wickes Hine (born September 26, 1874 – died November 3, 1940) was an American photographer. He also studied how people live in groups, which is called sociology. Hine used his camera to help make the world a better place. His powerful photos played a big part in changing laws about child labor in the United States.

Contents

Lewis Hine's Early Life

Lewis Hine was born in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, on September 26, 1874. When he was young, his father died in an accident. Hine then started working to save money for college.

He studied sociology at several universities, including the University of Chicago and New York University. Later, he became a teacher in New York City. At the Ethical Culture School, he taught his students to use photography for learning.

Hine often took his sociology classes to Ellis Island in New York Harbor. There, he photographed the many immigrants who arrived each day. Between 1904 and 1909, Hine took over 200 photos of these new arrivals. He soon realized that photography could be a strong tool for social change.

Using Photography for Change

In 1907, Hine became the official photographer for the Russell Sage Foundation. He took pictures of life in the steel-making areas of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. These photos were part of an important study called The Pittsburgh Survey.

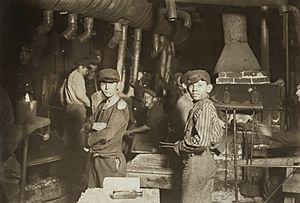

In 1908, Hine left his teaching job to work for the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC). For the next ten years, Hine took photos of children working. He focused on child labor in the Carolina Piedmont region. His photos helped the NCLC convince lawmakers to end child labor.

Hine's work for the NCLC was often risky. Factory police and bosses sometimes threatened him with violence. At that time, many people wanted to hide the unfairness of child labor. Taking photos was often forbidden and seen as a threat to businesses. To get inside mills, mines, and factories, Hine had to pretend to be many different people. Sometimes he was a fire inspector, a postcard seller, or even a bible salesman.

During and after World War I, Hine photographed the American Red Cross helping people in Europe. In the 1920s and early 1930s, Hine created "work portraits." These photos showed the important role people played in modern industries.

In 1930, Hine was asked to photograph the building of the Empire State Building. He took pictures of workers in dangerous spots, high up on the steel frame. He often took the same risks as the workers. To get the best views, Hine was swung out in a special basket, 1,000 feet above Fifth Avenue. He once said he was hanging above the city with "a sheer drop of nearly a quarter-mile" below him.

During the Great Depression, Hine worked for the Red Cross again. He photographed drought relief in the American South. He also worked for the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), documenting life in the mountains of eastern Tennessee. Hine was also the main photographer for the Works Progress Administration's National Research Project. This project studied how changes in industry affected jobs.

Later Life and Legacy

In 1936, Hine was chosen to be the photographer for the National Research Project. However, he did not finish his work there.

In his last years, Hine struggled to find work. He lost support from the government and companies. He wanted to join the Farm Security Administration photography project, but he was always turned down. Few people were interested in his old or new work. Hine lost his home and had to apply for welfare. He passed away on November 3, 1940, at the age of 66.

Hine's photographs were very important in helping the NCLC end child labor. In 1912, the Children's Bureau was created. Finally, the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 helped bring child labor in the U.S. to an end.

After Hine died, his son, Corydon, gave his photos and negatives to the Photo League. Later, the Museum of Modern Art was offered his pictures but did not accept them. However, the George Eastman Museum did.

In 2006, a book for middle schoolers called Counting on Grace was published. It tells the story of a 12-year-old girl named Grace. She meets Hine when he visits a cotton mill in Vermont that uses child laborers. The book's cover shows a famous photo of Addie Card, a real child worker Hine photographed.

In 2016, Time magazine published colorized versions of some of Hine's child labor photos.

Where to See Hine's Work

Hine's photographs are kept in many public collections, including:

- Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL

- Albin O. Kuhn Library & Gallery at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County – almost five thousand NCLC photographs

- George Eastman Museum – nearly ten thousand photographs and negatives

- Library of Congress – over 5,000 photographs, including his child labor, Red Cross, and WPA images.

- New York Public Library, New York

- International Photography Hall of Fame, St.Louis, MO

Famous Photographs by Lewis Hine

- Child Labor: Girls in Factory

- Breaker Boys (1910)

- Young Doffers in the Elk Cotton Mills (1910)

- Steam Fitter (1920)

- Workers, Empire State Building (1931)

Images for kids

-

Baseball team made mostly of child laborers from a glass factory in Indiana (1908)

-

"Addie Card, 12 years. Spinner in North Pormal (i.e., Pownal) Cotton Mill. Vt." (1910)

-

Pennsylvania coal breakers, (Breaker boys) (1912)

-

Empire State Building worker (1931)

-

Raising the Mast, Empire State Building (1932)

See also

In Spanish: Lewis Hine para niños

In Spanish: Lewis Hine para niños

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |