National Child Labor Committee facts for kids

The National Child Labor Committee (NCLC) was an important group in the United States. It worked to stop child labor and make sure children were treated fairly. Its main goal was to protect the rights, health, and education of children and young people when it came to work.

The NCLC was based in Manhattan, New York. It was run by a group of leaders called a board of directors.

Contents

How the NCLC Started

The idea for the National Child Labor Committee came from Edgar Gardner Murphy. He was a church leader and writer from America. He suggested forming the group after a meeting in New York City on April 25, 1904. Many people who cared about working children supported the idea. Felix Adler became the first leader of the NCLC.

The new group quickly got help from famous Americans. By November 1904, just a few months after it started, the NCLC had many important members. These included former president Grover Cleveland, Senator Benjamin Tillman, and Harvard University president Charles W. Eliot.

In 1907, the U.S. government officially recognized the NCLC. Its first leaders included well-known reformers like Jane Addams, Florence Kelley, and Lillian Wald. With these strong leaders, the NCLC quickly gained more support and began to take action.

Showing the Problem of Child Labor

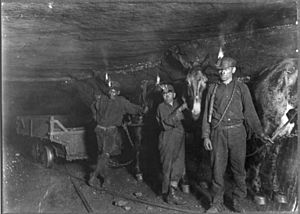

In 1900, about 1.7 million children under 16 had jobs in the United States. This was a big increase from earlier years. Many Americans were worried about this. They thought it was wrong for young people to work long hours for very little money in factories. From 1909 to 1921, the NCLC used this concern to push for changes against child labor.

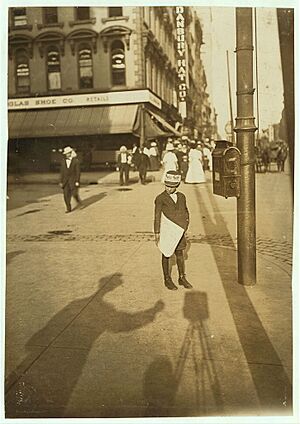

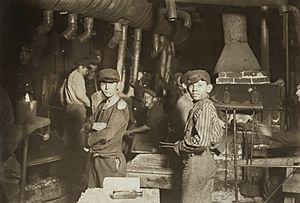

Lewis Hine's Photographs

In 1908, the NCLC hired Lewis Hine. He was a teacher and photographer who studied how people live in society. Hine believed that photos could teach people important things. He took pictures of children working in American industries. For the next ten years, Hine took thousands of photos to show the sad truth of child labor.

Hine photographed boys and girls working in mills, factories, and other jobs across the country. His pictures showed average Americans what life was like for working children. Hine said he "wanted to show things that had to be corrected." His photos helped many people support new laws against child labor. Hine's pictures became the public face of the NCLC. They are also some of the first examples of documentary photography in America.

Lewis Hine was a very important photojournalist before World War I. At that time, the American economy was growing fast. Businesses needed many workers. They looked for cheap labor, including immigrant workers and children. Factory jobs often needed small hands and energy, which children had.

Around the early 1900s, people started to think differently about child labor. Reformers argued that child labor trapped children in a cycle of poverty. They said that long work hours stopped children from getting an education and enjoying their childhood.

Hine often took risks to get his photos. He would sneak into factories where he was not welcome. He took pictures of things that factory managers wanted to hide. Sometimes, he was in danger of being attacked. He risked his life to show the truth about working children. Today, there is a Lewis Hine award that honors people who do great work helping young people.

Fighting Against Child Labor Laws

After it started in 1904, the NCLC began to push for child labor laws in each state. Two NCLC leaders, Owen Reed Lovejoy in the North and Alexander McKelway in the South, led these efforts. They investigated child labor conditions and talked to state lawmakers to pass new rules.

The NCLC had some success in the North. But by 1907, they had not made much progress in the Southern states, especially where there were many mills. So, the NCLC decided to try a different approach. They supported the first national bill against child labor, introduced in Congress in 1907. Even though this bill did not pass, it showed many people that states needed to work together to solve the problem.

The NCLC then asked for a federal children's bureau. This bureau would study and report on the lives of all American children. In 1912, the NCLC succeeded. A new United States Children's Bureau was created within the government. On April 9, President William Taft signed the law. For the next 30 years, this bureau worked with the NCLC to improve child labor laws across the country.

In 1915, the NCLC decided to focus its efforts on the federal government. Pennsylvania Congressman Alexander Mitchell Palmer introduced a bill to stop child labor in most American mines and factories. President Woodrow Wilson thought the bill was against the Constitution. Even though the House of Representatives voted for it, the bill did not pass in the Senate. However, this bill was important because it tried to use the government's power over trade to control working conditions for the first time.

In 1916, Senator Robert L. Owen and Representative Edward Keating introduced the Keating-Owen Act. This law, supported by the NCLC, stopped goods made by child labor from being shipped between states. President Woodrow Wilson signed it into law. But in 1918, the United States Supreme Court said the law was unconstitutional. The Court agreed that child labor was bad, but felt the law went too far beyond Congress's power to regulate trade. The bill was changed, but the Supreme Court again said it was unconstitutional.

The NCLC then tried to pass a federal constitutional amendment. In 1924, Congress passed the Child Labor Amendment. However, by 1932, only six states had approved it. Many more states were needed for it to become part of the Constitution. Today, this amendment is still technically waiting for more states to approve it.

In 1938, the NCLC supported the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA). This act included rules against child labor that the NCLC helped create. The law stops goods made by "oppressive child labor" from being shipped between states. "Oppressive child labor" means any job for children under 16, and dangerous jobs for children aged 16 to 18. This law does not include farm work or jobs where a child works for their own parents. On June 25, 1938, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the bill into law. The FLSA is still the main federal child labor law today.

During World War II, the NCLC made sure that the need for workers during the war did not weaken the new child labor laws. They worked to prevent children from going back to work in mines, mills, and on the streets.

Helping with Job Skills and Education

After World War II, the NCLC started to focus on new areas. They emphasized teaching children about the working world. They also supported programs to improve the education and health of children whose families moved around for farm work. Today, the NCLC's main goals include:

- Teaching children about different jobs.

- Stopping children and young people from being used unfairly in jobs.

- Making health and education better for children of migrant farmworkers.

- Helping more people know about the work done for children across the country.

In the 1950s and 60s, the NCLC helped with several important laws. These included the Manpower Development and Training Act and the Vocational Education Act.

In 1979, the NCLC helped create the National Youth Employment Coalition (NYEC). This group supports organizations that help young people become good citizens.

In 1985, the NCLC started the Lewis Hine Awards for Service to Children and Youth. These awards honor everyday Americans who do great work with young people. They also give special awards to well-known leaders for their amazing efforts.

From 1991 until it closed, the NCLC created and grew the Kids and the Power of Work (KAPOW) program. KAPOW connects businesses with elementary schools. Volunteers from businesses teach students about the world of work. Today, KAPOW is a model for similar programs. It operates in over 30 communities and helps more than 50,000 students.

The End of the NCLC

In its last years, the NCLC struggled to raise enough money. The problem it was created to fight, child labor, had largely ended. The NCLC is a rare example of a group that succeeded in its main goal and was no longer needed. After more than 100 years of fighting child labor, it closed down in 2017. Jeffrey Newman, the last president, said the NCLC decided to "declare victory and just move out."

Notable People

- Jane Addams

- Felix Adler

- Grover Cleveland

- Ann Washington Craton

- Edward Thomas Devine

- Deborah Donalds

- Charles William Eliot

- Florence Kelley

- Owen Reed Lovejoy

- Edgar Gardner Murphy

- Benjamin Tillman

- Loraine Bedsole Bush Tunstall

- Lillian Wald

See also

In Spanish: Comité Nacional del Trabajo Infantil (Estados Unidos) para niños

In Spanish: Comité Nacional del Trabajo Infantil (Estados Unidos) para niños

- Seebert Lane Colored School

- Timeline of children's rights in the United States

Images for kids