Florence Kelley facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

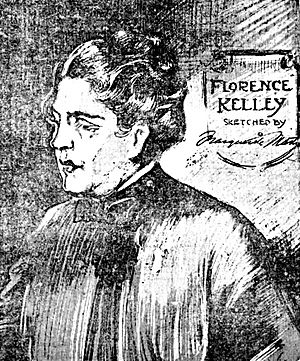

Florence Kelley

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Florence Moltrop Kelley

September 12, 1859 |

| Died | February 17, 1932 (aged 72) |

| Alma mater | Cornell University Northwestern University School of Law |

| Occupation | American social reformer |

| Spouse(s) | Lazare Wischnewetzky |

| Parent(s) | William D. Kelley and Caroline Bartram Bonsall |

Florence Moltrop Kelley (September 12, 1859 – February 17, 1932) was a brave American social reformer. She worked hard to make life better for many people. Florence fought against unfair workplaces called sweatshops. She also pushed for minimum wage, eight-hour workdays, and children's rights. Her efforts are still remembered and valued today.

Florence Kelley was the first general secretary of the National Consumers League. This group started in 1899. She also helped create the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909.

Contents

Early Life and Influences

Florence Kelley was born in Philadelphia on September 12, 1859. Her father, William D. Kelley, was a judge and a member of the US House of Representatives. He was also an abolitionist, meaning he fought to end slavery.

Florence learned a lot from her father. She said he taught her "everything that I have ever been able to learn to do." He read books about child labor to her. Even at age 10, she read her father's book, The Resources of California.

Florence's great-aunt, Sarah Pugh, was a Quaker and against slavery. Sarah refused to use cotton and sugar because they were linked to slave labor. This idea made a big impression on young Florence. Sarah also taught Florence about the challenges women faced.

Florence had seven siblings, but five of her sisters died when they were very young. These losses made Florence an early supporter of women's rights. She believed in giving women the right to vote.

In 1884, Florence married Lazare Wischnewetzky in Zurich, Switzerland. They had three children. The couple divorced in 1891. Florence moved to Chicago and raised her children. She kept her maiden name but preferred to be called "Mrs. Kelley."

Her Education Journey

When Florence was young, she was often sick. This meant she missed a lot of school. On those days, she spent time in her father's library. There, she read many different books.

In 1882, at age 16, Florence went to Cornell University. She was a very good student and wrote her main paper about children who were struggling. Her father's lessons about underprivileged children inspired this topic.

Florence wanted to study law at the University of Pennsylvania. However, she was not allowed to attend because she was a woman. Instead, she worked to help working women. She helped start and attended evening classes at the New Century Guild for Working Women.

Later, she studied at the University of Zurich in Europe. This was one of the first universities to give degrees to women. There, she joined a group of students who believed in socialism.

In 1894, Florence earned a law degree from Northwestern University School of Law. This allowed her to open a school for working girls in Pennsylvania.

Fighting for Social Justice

Florence Kelley believed strongly in social justice. She was a member of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. She also fought for women's right to vote and for African-American civil rights. She was a follower of Karl Marx and a friend of Friedrich Engels. Florence translated Engels' book, The Condition of the Working Class in England, into English in 1885. This translation is still used today.

She helped create the New Century Guild of Philadelphia. This group offered classes and programs to help working women. Florence herself taught evening classes there. The New Century Guild worked to improve working and living conditions for poor people in cities. They fought for laws like the minimum wage and the eight-hour workday.

In 1891, Florence joined the Hull House in Chicago. This was a famous settlement house where people lived and worked to help their communities. At Hull House, Florence met other important reformers like Jane Addams. They worked together to improve rights for working women and children. Hull House helped Florence become a leader in social activism. She is known for starting the social justice feminism movement.

In 1892, Florence investigated how people worked in Chicago's clothing factories. She found children as young as three years old working in crowded apartments. She also saw women working too many hours and risking their health.

Florence was part of many important groups. These included the National Child Labor Committee, the National Consumers League, and the NAACP.

Protecting Children at Work

Florence Kelley had seen glass factories at night with her father when she was young. She fought to make it illegal for children under 14 to work. She also wanted to limit the hours for children under 16. Florence believed children should be in school and have a chance to learn and grow.

From 1891 to 1899, Florence lived at the Hull House in Chicago. She took state lawmakers on tours of sweatshops to show them the terrible conditions. She convinced labor groups to support new laws. In 1893, she became the first woman to hold a statewide office in Illinois. Governor Peter Altgeld made her the Chief Factory Inspector. This was a new job, and it was very unusual for a woman to have such a powerful role. She chose five women and six men to help her.

Florence was known for being strong and energetic. Jane Addams' nephew called her "the toughest customer in the reform riot." He said she was the best fighter for a good life for others that Hull House ever knew.

Florence found that some employees worked up to 16 hours a day, seven days a week. Their wages were often too low to support their families. Because of her work, Illinois passed its first factory law in 1893. This law limited women's work to eight hours a day. It also stopped children under 14 from working. This marked the start of the Progressive Era in social reform.

Helping African Americans

Florence Kelley was a founding member of the NAACP. She was asked to join by William English Walling and Mary White Ovington. As a board member, she worked on committees about education and fair spending of school money. W. E. B. Du Bois said Florence was known for asking tough questions to find the best way forward. She spoke publicly about racial inequality.

In 1913, she studied how the government spent money on education. She saw that white schools often received much more money than black schools. This led her to work against a bill that would have given much less money to teachers of black children. Florence wanted to add language to the bill to make sure funding was fair for everyone, no matter their race.

Florence also disagreed with the NAACP and W.E.B. DuBois on some issues. For example, the Sheppard-Towner Act helped mothers and babies. The NAACP worried it wouldn't prevent discrimination against black mothers. Florence believed it was more important to pass the law first. She thought getting the funding secured was the main goal. She promised to work for fairness later. Eventually, the NAACP supported her.

In 1917, Florence marched in a silent protest parade in New York. This protest was against violence toward black people in East St. Louis, Illinois. She used her connections in Congress to fight against unfair laws. In 1921, she pushed the NAACP to oppose bills that spent less money on schools for black children. Florence helped start the tradition of protesting against racial discrimination.

Florence and other NAACP leaders protested against the film "The Birth of a Nation." They felt it showed a racist view of black people. In 1923, Florence worked hard to get the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs included in the Women's Joint Congressional Committee. By January 1924, she succeeded.

National Consumers League and Fair Work Hours

From 1899 to 1926, Florence lived at the Henry Street Settlement in New York City. From there, she started and led the National Consumers League (NCL). This group was strongly against sweatshops. She worked to make people aware of unfair working conditions. She also helped pass state laws to protect workers, especially women and children.

The NCL created a "Code of Standards." This code aimed to raise wages, shorten work hours, and ensure clean workplaces. Florence used the NCL to gather information and push for her policies. She also guided younger activists, like Mary van Kleeck.

She helped build 64 Consumers Leagues across the country. Florence often spoke to state lawmakers. She worked hard to establish an eight-hour workday. In 1907, she helped with a Supreme Court case called Muller v. Oregon. This case tried to overturn limits on how many hours women could work. Florence helped create the famous Brandeis Brief. This document used facts about society and health to show the dangers of long work hours. This set a new example for the Supreme Court to consider such evidence.

In 1909, Florence helped create the NAACP. She became a friend and ally of W. E. B. Du Bois. She also continued to work to improve child labor laws and working conditions.

In 1917, she again helped with a Supreme Court case, Bunting v. Oregon. This case also pushed for an eight-hour workday for factory workers.

The NCL, led by Florence, created a "Consumer's 'white label'" for clothing. This label meant the clothes were made without child labor and followed state laws for good working conditions. She led the National Consumers League until she passed away in 1932.

Other Important Work

In 1907, Florence Kelley helped organize New York's Committee on Congestion of Population. She also worked with Josephine Clara Goldmark on the Brandeis Brief. This brief showed how working too many hours harmed women's health.

Florence also helped convince Congress to pass the Keating-Owen Child Labor Act in 1916. This law banned the sale of products made in factories that used child labor. She also pushed for the Sheppard–Towner Act. This act created the first national social welfare program. It aimed to fight against mothers and babies dying by funding health clinics.

In 1912, she helped form the US Children's Bureau. This was a federal agency created to look after the well-being of children.

Death

Florence Kelley passed away at age 72 in Germantown, Philadelphia on February 17, 1932. She is buried in Philadelphia's Laurel Hill Cemetery.

She was recognized as an "Angel hero" by The My Hero Project.

See also

In Spanish: Florence Kelley para niños

In Spanish: Florence Kelley para niños