The Birth of a Nation facts for kids

Quick facts for kids The Birth of a Nation |

|

|---|---|

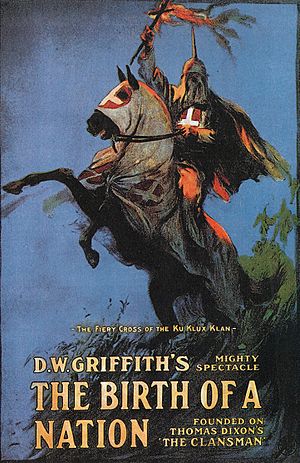

Theatrical release poster

|

|

| Directed by | D. W. Griffith |

| Produced by |

|

| Screenplay by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Music by | Joseph Carl Breil |

| Cinematography | Billy Bitzer |

| Editing by | D. W. Griffith |

| Studio | David W. Griffith Corp. |

| Distributed by | Epoch Producing Co. |

| Release date(s) | February 8, 1915 |

| Running time | 12 reels 133–193 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language |

|

| Budget | $100,000+ |

| Money made | $50–100 million |

The Birth of a Nation, first called The Clansman, is a 1915 American silent epic drama film. It was directed by D. W. Griffith and starred Lillian Gish. The movie's story comes from Thomas Dixon Jr.'s 1905 novel and play The Clansman. Griffith helped write the story with Frank E. Woods and produced the film with Harry Aitken.

This film is very important in movie history. It was praised for its amazing technical skills. It was the first American movie that was 12 reels long and not a serial. The story mixes fiction and history. It shows the assassination of Abraham Lincoln and follows two families during the Civil War and Reconstruction eras. These families are the Stonemans from the North and the Camerons from the South. The movie was first shown in two parts with a break in between. It was also the first American film to have a full musical score played by an orchestra.

The Birth of a Nation was groundbreaking for its time. It used closeups and fadeouts. It also had a huge battle scene with hundreds of extras, which was a first. The movie was even shown at the White House to President Woodrow Wilson and his family.

However, the film has always been very controversial. Many people call it "the most controversial film ever made in the United States" and "the most racist film in Hollywood history." While it shows Abraham Lincoln in a good light, the movie is known for its racist portrayal of African Americans. It shows black people (many played by white actors in blackface) as not smart and aggressive towards white women. The Ku Klux Klan (KKK) is shown as heroes who protect American values and white women.

The film was very popular with white audiences across the U.S. Its success helped increase racial segregation. In response, African Americans protested the film. Groups like the NAACP tried to get it banned. They argued it caused racial tension and could lead to violence. Because of these efforts to ban his film, Griffith made another movie called Intolerance the next year.

Despite the controversy, The Birth of a Nation was a huge success financially. It made more money than any movie before it. It also greatly influenced the film industry and American culture. The movie is even seen as an inspiration for the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan a few months after its release. In 1992, the Library of Congress chose the film for preservation in the National Film Registry. This means it is considered "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."

Contents

The Story of the Film

The movie is split into two main parts. The first part ends with the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. After this, there is a break.

Part 1: The Civil War Years

The story follows two families: the Stonemans from the North and the Camerons from the South. Austin Stoneman, a U.S. Representative, is from the North. He has a daughter and two sons. The Cameron family from the South includes Dr. Cameron, his wife, three sons, and two daughters.

Phil, the older Stoneman son, falls in love with Margaret Cameron when he visits the Cameron home in South Carolina. Young Ben Cameron admires a picture of Elsie Stoneman. When the Civil War begins, the young men from both families join their armies. The younger Stoneman son and two Cameron brothers die in the war.

Meanwhile, Confederate soldiers save the Cameron women from an attack by a black militia. Ben Cameron leads a brave charge in a battle, earning the nickname "the Little Colonel." He gets hurt and is captured. He is taken to a Union hospital in Washington, D.C..

At the hospital, Ben meets Elsie Stoneman, the nurse whose picture he carried. Elsie helps Ben's mother convince Abraham Lincoln to pardon Ben. But after Lincoln is assassinated, his plans for peace after the war end. Austin Stoneman and other politicians want to punish the South. The movie shows this as a harsh time called the Reconstruction Era.

Part 2: The Reconstruction Era

Stoneman and his helper, Silas Lynch, go to South Carolina to see how Reconstruction policies are working. During an election, Lynch is elected lieutenant governor. The film shows black people putting extra ballots into boxes, while many white people are not allowed to vote. The new legislature, mostly black members, is shown acting in a way that uses old stereotypes.

Ben Cameron is inspired by white children pretending to be ghosts to scare black children. He decides to fight back by forming the Ku Klux Klan. Because of this, Elsie ends her relationship with Ben. Later, Flora Cameron goes into the woods and is followed by Gus, a former soldier. He tries to force her to marry him. Frightened, she runs away. Trapped on a cliff, Flora jumps to her death to escape Gus. Ben finds her as she dies and carries her body home. The Klan then hunts down Gus and hangs him.

Lynch orders a crackdown on the Klan after Gus's death. He also passes a law allowing mixed-race marriages. Dr. Cameron is arrested for having Ben's Klan uniform. Phil Stoneman and some black servants rescue him. They flee with Margaret Cameron. They hide in a small hut with two helpful former Union soldiers. A title card says, "The former enemies of North and South are united again in common defense of their Aryan birthright."

Congressman Stoneman leaves to avoid trouble with Lynch. Elsie goes to Lynch to ask for Dr. Cameron's release. Lynch tries to force Elsie to marry him. Elsie faints. Stoneman returns, and Elsie is moved to another room. Stoneman is angry when he learns Lynch wants to marry his daughter against her will. Klansman spies find Elsie and get help. Elsie screams for help. The Klan, led by Ben, rides in to take control of the town. They rescue Elsie and capture Lynch.

Meanwhile, Lynch's militia attacks the hut where the Camerons are hiding. The Klansmen arrive just in time to save them. On the next election day, black people see armed Klansmen outside their homes and are scared away from voting.

The film ends with a double wedding. Margaret Cameron marries Phil Stoneman, and Elsie Stoneman marries Ben Cameron. The movie shows people being oppressed by a giant warlike figure, who then disappears. The scene changes to people finding peace under the image of Jesus Christ. The final message hopes for a time when war will end and peace will rule.

Meet the Actors

Main Actors

- Lillian Gish as Elsie Stoneman

- Mae Marsh as Flora Cameron

- Henry B. Walthall as Colonel Benjamin Cameron ("The Little Colonel")

- Miriam Cooper as Margaret Cameron

- Mary Alden as Lydia Brown, Stoneman's housekeeper

- Ralph Lewis as Austin Stoneman

- George Siegmann as Silas Lynch

- Walter Long as Gus

- Wallace Reid as Jeff, the blacksmith

- Joseph Henabery as Abraham Lincoln

- Elmer Clifton as Phil Stoneman

- Robert Harron as Tod Stoneman

- Josephine Crowell as Mrs. Cameron

- Spottiswoode Aitken as Dr. Cameron

- George Beranger as Wade Cameron

- Maxfield Stanley as Duke Cameron

- Jennie Lee as Mammy

- Donald Crisp as General Ulysses S. Grant

- Howard Gaye as General Robert E. Lee

Other Actors

- Harry Braham as Cameron's faithful servant

- Edmund Burns as Klansman

- David Butler as Union soldier / Confederate soldier

- William Freeman as Jake

- Sam De Grasse as Senator Charles Sumner

- Olga Grey as Laura Keene

- Russell Hicks

- Elmo Lincoln as ginmill owner / slave auctioneer

- Eugene Pallette as Union soldier

- Harry Braham as Jake / Nelse

- Charles Stevens as volunteer

- Madame Sul-Te-Wan as woman with gypsy shawl

- Raoul Walsh as John Wilkes Booth

- Lenore Cooper as Elsie's maid

- Violet Wilkey as young Flora

- Tom Wilson as Stoneman's servant

- Donna Montran as belles of 1861

- Alberta Lee as Mrs. Mary Todd Lincoln

- Allan Sears as Klansmen

- Dark Cloud as General at Appomattox Surrender

- Vester Pegg

- Alma Rubens

- Mary Wynn

- Jules White

- Monte Blue

- Gibson Gowland

- Fred Burns

- Charles King

How the Film Was Made

Filming the Movie

Filming for The Birth of a Nation started on July 4, 1914, and finished by October 1914. Some scenes were shot in Big Bear Lake, California. Engineers from West Point helped with the Civil War battle scenes. They even provided artillery for the film. Many war scenes were inspired by historical books and photos.

Many African American characters in the film were played by white actors in blackface. Griffith said this was on purpose. However, black extras, including Madame Sul-Te-Wan, were also in many scenes.

The movie's budget started at $40,000 but grew to over $100,000. Griffith shot about 150,000 feet of film, which is about 36 hours. He then edited it down to 13,000 feet, which is just over 3 hours. Some scenes were cut after early showings based on what audiences thought. Also, the mayor of New York City, John Purroy Mitchel, insisted on cutting some very racist scenes before the film was released there.

The Music Score

Even though The Birth of a Nation was a silent film, its music was very important. It was common to send music notes or full scores with each film.

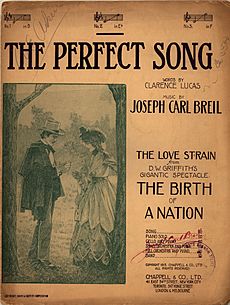

Composer Joseph Carl Breil created a three-hour musical score for the film. It used three types of music: parts of classical songs, new versions of well-known tunes, and original music. Breil's score was not used for the first showing in Los Angeles. But it was used when the film opened in New York.

Breil used parts of classical music by composers like Carl Maria von Weber and Ludwig van Beethoven. He also arranged popular songs like "Dixie" and "The Star-Spangled Banner". He even used "Ride of the Valkyries" by Richard Wagner for the KKK's ride.

Breil also wrote original music for different characters. The main love theme for Elsie Stoneman and Ben Cameron was called "The Perfect Song." This was one of the first "theme songs" from a movie to be sold to the public.

Film Release and Impact

First Showings

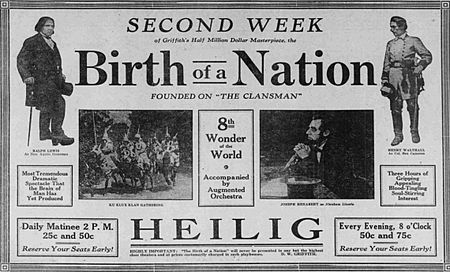

The film, then called The Clansman, was first shown on January 1 and 2, 1915, in Riverside, California. It was very popular and sold out. On February 8, 1915, it was shown to 3,000 people in downtown Los Angeles.

The filmmakers knew they needed a big advertising campaign because the movie cost so much to make. They decided to release the film in a special "roadshow" style. This meant they charged higher ticket prices and sold souvenirs. This helped build excitement before the film was shown everywhere.

New Title and White House Showing

The title was changed to The Birth of a Nation before its New York opening on March 2.

The Birth of a Nation was the first movie ever shown inside the White House. This happened on February 18, 1915, in the East Room. President Woodrow Wilson, his family, and his Cabinet members watched it. The film's director, D. W. Griffith, and writer, Thomas Dixon, were there.

There is some debate about what President Wilson thought of the movie. Some newspapers reported that he received many letters protesting his supposed support for the film. Wilson's secretary said that the President did not know the film's content beforehand and never approved it. However, Dixon claimed Wilson said he was "pleased" to show the film. Dixon and Wilson had known each other from college.

The film included quotes from Wilson's book, History of the American People, in its intertitles. These quotes supported the film's view of history, especially about the South and the KKK. Later, a magazine reported that Wilson said the film was "like writing history with lightning. And my only regret is that it is all so terribly true." Historians disagree if he actually said it was "terribly true."

Other Important Showings

The day after the White House showing, Griffith and Dixon showed the film at the Raleigh Hotel ballroom. Edward Douglass White, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, agreed to see the film after Dixon told him it was the "true story" of Reconstruction. White said he had been a member of the Klan in his youth. The entire Supreme Court, many members of Congress, and other important people watched the film. The audience of 600 people cheered and applauded.

These special showings gave the film a lot of "honor." Dixon and Griffith used this to promote the movie. When the film went to the National Board of Censorship in New York City, they presented it as "endorsed" by the President and other important people. The Board approved the film.

However, Justice White was very angry when advertisements said he approved the film. He threatened to speak out against it. Dixon, who was a white supremacist, denied having anti-black prejudices. He believed his film would change Northern opinions and make them support the South.

New Opening Messages

On its second release, Griffith added new opening messages to the film. These messages defended the movie. They said:

- A PLEA FOR THE ART OF THE MOTION PICTURE:*

- We do not fear censorship, for we have no wish to offend with improprieties or obscenities, but we do demand, as a right, the liberty to show the dark side of wrong, that we may illuminate the bright side of virtue—the same liberty that is conceded to the art of the written word—that art to which we owe the Bible and the works of Shakespeare and If in this work we have conveyed to the mind the ravages of war to the end that war may be held in abhorrence, this effort will not have been in vain.*

Film historians have different ideas about these messages. Some think they show Griffith trying to make his film seem like a serious historical story. Others say Griffith was trying to hide the film's true meaning behind ideas of art and freedom.

Images for kids

-

Film's portrayal of John Wilkes Booth assassinating President Abraham Lincoln

See also

In Spanish: El nacimiento de una nación para niños

In Spanish: El nacimiento de una nación para niños