William D. Kelley facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

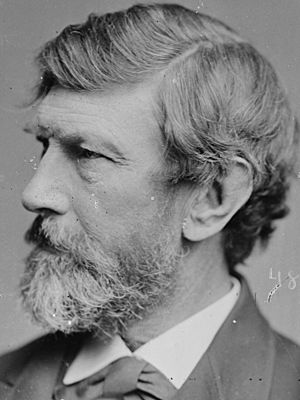

William D. Kelley

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Pennsylvania's 4th district |

|

| In office March 4, 1861 – January 9, 1890 |

|

| Preceded by | William Millward |

| Succeeded by | John E. Reyburn |

| Personal details | |

| Born | April 12, 1814 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, US |

| Died | January 9, 1890 (aged 75) Washington, D.C., US |

| Resting place | Laurel Hill Cemetery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Political party | Democratic Republican |

| Spouse | Caroline Bartram-Bonsall |

| Children | Elizabeth Florence Marian Josephine Anna Kelley William Darrah, Jr. Albert Bartram Caroline |

| Profession | Proofreader Jeweler Attorney Judge Legislator |

| Signature | |

William Darrah Kelley (born April 12, 1814 – died January 9, 1890) was an American politician from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He was a member of the Republican Party and served in the U.S. House of Representatives for Pennsylvania's 4th congressional district from 1861 to 1890.

Kelley was a strong supporter of ending slavery. He was a friend of President Abraham Lincoln and helped start the Republican Party in 1854. He believed that African Americans should be allowed to join the army during the American Civil War. After the war, he worked to give them the right to vote. He also strongly believed in protective tariffs, which are taxes on imported goods. He was so committed to this idea that he refused to wear any clothing made in another country.

Contents

Early Life and Family

William Darrah Kelley was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. His father, David Kelley, was a watch and clock-maker who died when William was only two years old. William later bought one of his father's clocks to keep in his own home.

After his father's death, William's mother, Hannah, opened a boarding house to support her children. A kind Quaker woman helped the family by pretending to claim some of their belongings before an auction. This way, the family could get their items back after the auction.

Starting His Career

As a young boy, William worked as an errand boy in a bookstore in Philadelphia. This job led him to become a proofreader for the Philadelphia Inquirer newspaper.

Later, he trained to be a jeweler. He also served in a local militia group called the State Fencibles. After working as a jeweler in Boston, Massachusetts, he returned to Philadelphia. There, he began studying law in the office of Colonel John Page, a well-known attorney. William Kelley became a lawyer in Philadelphia in 1841.

One reporter described Kelley as someone who "hammered his way up in life." This meant he worked very hard to succeed, even though he faced challenges.

Becoming a Judge

William Kelley first became involved in politics as a member of the Democratic Party. He was against slavery. In 1846, Governor Francis R. Shunk appointed him as a Judge for the Philadelphia County Court of Common Pleas. He served as a judge until 1856.

Kelley became known across the country after a major speech he gave in 1854. In this speech, he spoke out against the slave trade. His speech, called "Slavery in the Territories," was published and read by many people. In 1884, he was elected as a member of the American Philosophical Society, a group that promotes useful knowledge.

Political Journey

Founding the Republican Party

In 1854, a law called the Kansas-Nebraska Act was passed, which allowed new territories to decide if they would have slavery. This law upset many people, including William Kelley. He left the Democratic Party and became one of the people who helped create the Republican Party.

Fighting for Rights

Kelley was elected to Congress as a Republican in 1860. He started serving on March 4, 1861, and remained in office until he died. He was good friends with Abraham Lincoln. Kelley was part of the group that told Lincoln he had been chosen to run for president in 1860.

During the Civil War, Kelley was a key figure in the Union League of Philadelphia. He was one of the first people to suggest that African Americans should be allowed to join the Union army. After the war ended, he was part of the group that attended the ceremony when the United States flag was raised again over Fort Sumter.

Kelley often spoke about the importance of "impartial suffrage," meaning voting rights for African Americans. He introduced a bill in the 39th United States Congress that gave African Americans in Washington, D.C. the right to vote. This bill became law. He also supported the idea of removing President Johnson from office because Johnson had opposed important civil rights laws.

Key Roles in Congress

William Kelley held several important positions in the House of Representatives. He was the Chairman of the House Committee on Coinage, Weights, and Measures from 1867 to 1873. He also chaired the Ways and Means Committee from 1881 to 1883, and the Committee on Manufactures from 1889 to 1890.

"Pig-Iron" Kelley and Tariffs

In his later career, Kelley was most famous for supporting high protective tariffs. These tariffs were taxes on goods imported from other countries. He believed these taxes would protect American businesses, especially those making iron and steel in Pennsylvania. Because of his strong support for these industries, he was nicknamed "Pig-Iron" Kelley.

Kelley truly believed in protective tariffs. He would not wear any clothes or use any items made in a foreign country. He often encouraged his friends to do the same. Even though some people thought he might be profiting from his views, he never had any financial investments in ironworks or mining.

Yellowstone National Park Idea

In 1871, William Kelley was the first politician in Washington to suggest creating what would later become Yellowstone National Park. He proposed that Congress should set aside the Great Geyser Basin as a public park forever.

Public Scrutiny

In 1872, Kelley was among some congressmen accused of being involved in a financial issue related to the company building the Union Pacific Railroad. Kelley stated he had agreed to buy shares but hadn't paid for them yet. He believed the shares were later sold, and he received the difference. He maintained his innocence and pointed out that he had never been accused of dishonesty in other areas, such as during the Civil War. A motion to officially criticize him was discussed but ultimately not acted upon.

Military Service

Even though members of Congress were not required to serve in the military, Kelley volunteered during the American Civil War. In September 1862, he joined a home guard unit called the Independent Artillery Company. He served as a Private during his time of enlistment.

Character and Legacy

William Kelley was known as one of the hardest-working members of Congress. People described him as generous and honorable. He was a dedicated scholar who spent his free time studying important topics. He was generous with his money but lived simply himself. Even his opponents saw him as a warm-hearted person.

When he died, he had a good amount of money, mostly from real estate investments. However, newspaper reports noted that he never made money from his political office and never tried to. He even paid for his own postage on letters and refused free railroad passes, which were common at the time.

Death and Burial

William Kelley was a regular smoker. He died from health issues related to his mouth and throat, which he had suffered from for about six years. He was buried at Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia.

Family Life

William Kelley's daughter, Florence Kelley, became a very important social reformer. She was connected with Hull House, a famous settlement house that helped people in need.

His granddaughter, Martha Mott Kelley, wrote mystery novels using the pen name Patrick Quentin.

Works

Speeches

- Slavery in the Territories (1854)

Books

- The Equality of All Men Before the Law: Claimed and Defended (1865)

- Reasons for Abandoning the Theory of Free Trade and Adopting the Principle of Protection to American Industry (1872)

- Speeches, Addresses (1872)

- Letters on Industrial and Financial Questions (1872)

- Letters from Europe (1880)

- The Old South and the New (1887)

Images for kids

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |