1912 Lawrence textile strike facts for kids

Quick facts for kids 1912 Lawrence textile strike |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

Massachusetts militiamen with fixed bayonets surround a group of strikers

|

|||

| Date | January 11 – March 14, 1912 | ||

| Location | |||

| Goals | 54-hour week, 15% increase in wages, double pay for overtime work, and no bias towards striking workers | ||

| Methods | Strikes, protests, demonstrations | ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

|||

| Lead figures | |||

|

|||

| Arrests, etc | |||

|

|||

The Lawrence Textile Strike, also known as the Bread and Roses Strike, was a major strike by immigrant workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts, in 1912. It was led by a group called the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). The strike started because a new law shortened the workweek for women, but their pay was also cut.

This strike quickly grew to include over 20,000 workers from almost every mill in Lawrence. It began on January 11, 1912, after workers found their pay had been reduced. The strike brought together people from more than 51 different countries. Many of them did not speak English. A large number of the striking workers were Italian immigrants.

The strike lasted over two months, through a very cold winter. It showed that immigrant workers, many of whom were women, could organize and fight for their rights. When a worker named Anna LoPizzo was killed during a protest, IWW organizers Joseph Ettor and Arturo Giovannitti were falsely accused and arrested for her murder.

IWW leaders Bill Haywood and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn came to Lawrence to help manage the strike. They came up with a famous idea: sending hundreds of the hungry children of striking workers to live with supportive families in New York, New Jersey, and Vermont. This move gained a lot of public sympathy. Even more sympathy came when police violently stopped another group of children from leaving at the Lawrence train station.

After this, the U.S. Congress held hearings. These hearings showed the terrible conditions in the Lawrence mills. Mill owners soon agreed to end the strike. They gave workers in Lawrence and across New England pay raises of up to 20 percent. However, the IWW's influence in Lawrence faded within a year.

The Lawrence strike is often called the "Bread and Roses" strike. This phrase comes from a poem by James Oppenheim, published in 1911. It became strongly linked to the strike because it captured the idea that workers wanted not just enough to live ("bread") but also a better quality of life and dignity ("roses").

Here are some lines from the poem that became a rallying cry:

As we come marching, marching, we battle too for men,

For they are women's children, and we mother them again.

Our lives shall not be sweated from birth until life closes;

Hearts starve as well as bodies; give us bread, but give us roses!—James Oppenheim

Contents

Why the Strike Happened

The city of Lawrence, Massachusetts was founded in 1845. It was a busy textile city but had many problems. By 1900, machines made it easier for factory owners to hire many unskilled immigrant workers, especially women. Work in a textile mill was very hard, fast, and dangerous. About one-third of workers in Lawrence textile mills died before they turned 25.

Many children under 14 also worked in the mills. Half of the workers in the four Lawrence mills of the American Woolen Company were girls between 14 and 18. It was common for people to lie about birth dates so younger girls could work. Lawrence had one of the highest child death rates in the country at that time.

By 1912, the Lawrence mills employed about 32,000 people. Conditions had gotten even worse. A new system made workers use two looms instead of one, which sped up the work greatly. This allowed factory owners to fire many workers. Those who kept their jobs earned very little, about $8.76 for 56 hours of work.

The president of the American Woolen Company, William Wood, owned some of the mills and worker housing. He claimed he could not afford to pay workers for the two hours they lost each week. This was despite his company making a profit of $3,000,000 in 1911.

Workers in Lawrence lived in crowded and unsafe apartment buildings. Many families shared small spaces. They often ate only bread, molasses, and beans. One worker told Congress that eating meat felt like a holiday. Half of the children died before age six. The average life expectancy for adults was only 39 years.

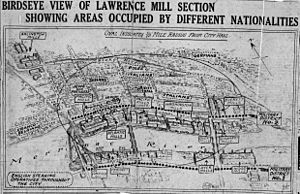

The mills and the community were divided by ethnic groups. Most skilled jobs went to native-born workers of English, Irish, and German backgrounds. Unskilled jobs were mostly done by French-Canadian, Italian, Slavic, Hungarian, Portuguese, and Syrian immigrants. Some skilled workers belonged to the American Federation of Labor (AFL), but few paid their dues. The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) had also been organizing in Lawrence for five years but had only a few hundred members.

The Strike Begins

On January 1, 1912, a new law in Massachusetts reduced the workweek for women and children from 56 hours to 54 hours. Workers were worried this would cut their pay. For the first two weeks of January, unions watched to see how mill owners would react. On January 11, some Polish women workers at the Everett Mill found their pay had been cut by about $0.32. They walked out of the mill.

The next day, workers at the American Woolen Company's Washington Mill also found their wages cut. They were ready for this and walked out, shouting "short pay, all out!"

Joseph Ettor of the IWW had been organizing in Lawrence. He and Arturo Giovannitti quickly became leaders of the strike. They formed a strike committee of 56 people, with four representatives from each of 14 different nationalities. This committee made all the big decisions. They made sure strike meetings were translated into 25 languages. Their demands included a 15% pay raise for a 54-hour work week, double pay for overtime, and no punishment for striking workers.

The city reacted by ringing its alarm bell, which had never happened before. The mayor sent local militia to patrol the streets. When mill owners used fire hoses on picketers, the workers threw ice, breaking windows. Twenty-four workers were jailed for a year for throwing ice. The judge said, "The only way we can teach them is to deal out the severest sentences." The governor then sent in the state militia and police, leading to many arrests.

The United Textile Workers (UTW), another union, tried to stop the strike. They claimed to speak for the Lawrence workers. But the striking workers ignored them. The IWW had successfully united workers from different ethnic groups. They had leaders who could speak many languages and share Ettor's message to avoid violence.

The IWW succeeded because it supported all workers from all mills. The AFL and mill owners wanted to deal with each mill and its workers separately. However, a leader from an AFL-affiliated group criticized the UTW president. This, along with mistakes by mill owner William Madison Wood, quickly turned public opinion in favor of the strikers.

A local undertaker tried to frame the strike leaders by planting dynamite in town. He was fined but not jailed. Later, it was shown that William M. Wood, the president of the American Woolen Company, had made a large payment to this person shortly before the dynamite was found.

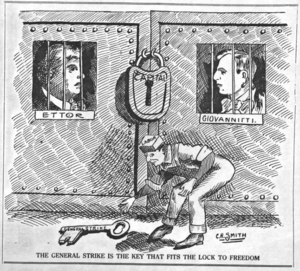

Authorities later falsely accused Ettor and Giovannitti of being involved in the murder of striker Anna LoPizzo, who was likely shot by police. Ettor and Giovannitti were miles away speaking to other workers. They and a third person were held in jail for months. The authorities declared martial law, banned public meetings, and sent more militia to patrol the streets. Even Harvard students were offered special exemptions from exams if they helped break the strike.

Children's Role in the Strike

The IWW responded by sending Bill Haywood, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, and other organizers to Lawrence. Haywood traveled to other New England textile towns to raise money for the strikers, which was very successful. The IWW set up relief committees, soup kitchens, and food distribution. Volunteer doctors provided medical care.

The IWW also raised money nationwide to give weekly payments to strikers. To show how much the strikers needed help, they arranged for hundreds of children to go live with supporters in New York City during the strike.

On February 24, city authorities tried to stop another 100 children from going to Philadelphia. Police and militia went to the train station to stop the children and arrest their parents. Police began hitting both children and their mothers. They dragged them away to be taken by truck. One pregnant mother was injured. The press was there and reported widely on the attack. Many women and children refused to pay fines and chose to go to jail, some with babies.

This police action against mothers and children gained national attention. Even Helen Herron Taft, the wife of President William Howard Taft, became interested. Soon, both the House and Senate began investigating the strike. In early March, a special House Committee heard stories from some of the strikers' children. They also heard from city, state, and union officials. Both parts of Congress published reports describing the terrible conditions in Lawrence.

The children involved in the police riot were not only the children of striking workers, but they were also workers themselves. Most mill workers were women and children. Families suffered from the lost income of both adults and children.

Children were used several times to draw attention to the strike. On February 10, 119 children were sent to Manhattan to live with relatives or strangers. This helped ease the financial burden on striking families. The children were welcomed in New York by cheering crowds, which brought national attention. When another group of children went to New York, they paraded down 5th Avenue, gaining even more attention.

Embarrassed by the bad publicity, the city marshal tried to stop the next group of children going to Philadelphia. This led to the violent clash at the train station. The children also gave powerful testimony about the working conditions in the factories. The national sympathy for the children helped change the outcome of the strike.

The national attention worked. The mill owners offered a 5% pay raise on March 1, but the workers rejected it. The American Woolen Company finally agreed to most of the strikers' demands on March 12, 1912. They agreed to change the "Premium System," where workers' extra pay depended on monthly production. Now, this extra pay would be given every two weeks instead of every four. Other textile companies in New England followed suit to avoid similar strikes.

The children who had been staying with supporters in New York City returned home on March 30.

Aftermath and Legacy

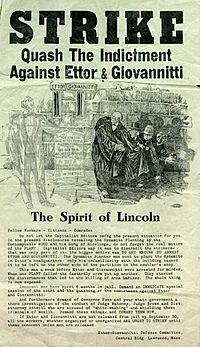

Ettor and Giovannitti, the IWW members, stayed in prison for months after the strike ended. Haywood threatened a general strike to demand their freedom, saying, "Open the jail gates or we will close the mill gates." The IWW raised $60,000 for their defense. They held protests and large meetings across the country. The authorities in Boston even arrested members of their defense committee.

On March 10, 1912, about 10,000 protestors gathered in Lawrence demanding Ettor and Giovannitti's release. Then, on September 30, 15,000 Lawrence workers went on a one-day strike for their release. Workers in Sweden and France even suggested boycotting American woolen goods. Italian supporters protested outside the U.S. consulate in Rome.

Meanwhile, a building contractor named Ernest Pitman, who worked for the American Woolen Company, told a district attorney that he had attended a meeting where the plan to frame the union by planting dynamite was made. Pitman died shortly after being called to testify. Wood, the American Woolen Company owner, was officially cleared of wrongdoing.

The trial of Ettor, Giovannitti, and a third person, Giuseppe Caruso, began in September 1912. Caruso was accused of firing the shot that killed the picketer. The three defendants were kept in steel cages in the courtroom. All witnesses said that Ettor and Giovannitti were miles away. Caruso was at home eating dinner when the killing happened.

Ettor and Giovannitti both gave powerful final statements at the end of the two-month trial. Ettor said that ideas cannot be stopped by punishment. He believed that what is seen as a crime in one time might become a widely accepted belief in another.

All three defendants were found not guilty on November 26, 1912.

However, the workers lost almost all the gains they had won in the next few years. The IWW did not believe in written contracts, thinking they made workers stop fighting for their rights. This allowed mill owners to slowly take away the wage increases and better working conditions. They also fired union activists and used spies to watch workers. Some owners even laid off more employees during a tough time for the industry.

The IWW then focused on supporting silk industry workers in Paterson, New Jersey. The 1913 Paterson silk strike was not successful.

Casualties

The strike had at least three people who died:

- Anna LoPizzo, an Italian immigrant, was shot in the chest during a clash between strikers and police.

- John Ramey, a Syrian youth, was stabbed with a bayonet by the militia.

- Jonas Smolskas, a Lithuanian immigrant, was beaten to death several months after the strike ended for wearing a pro-labor pin.

Conclusion

After the strike, workers kept some of the improvements they had fought for. Some workers went back to the mills, while others tried to find different jobs. The 1912 strike was the first of many that eventually led to the textile industry leaving New England by the mid-1900s. On February 9, 2019, Senator Elizabeth Warren announced her plan to run for President of the United States at the site of the strike.

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |