Pennines facts for kids

The Pennines, also called the Pennine Chain or Pennine Hills, are a range of uplands mostly found in Northern England. People often call them the "backbone of England" because they are long and run through the middle of the country. The range stretches from the northern Midlands up to North East England, close to the Anglo-Scottish border. The Peak District is at the southern end of the Pennines. It rises northwards from the flat areas near the Trent Valley in northern Staffordshire, and then goes into eastern Cheshire and southern Derbyshire. Further north are the South Pennines, Yorkshire Dales, and North Pennines, which end at the Tyne Gap. Beyond this gap are the Border Moors and Cheviot Hills, which some people also include as part of the Pennines.

The Pennines have many deep valleys. The range is split into two by the Aire Gap, a wide pass formed by the valleys of the rivers Aire and Ribble. There are several smaller hill ranges, called spurs, that branch off the main Pennine range to the east of the gap, going into Lancashire. These include the Rossendale Fells, West Pennine Moors, and the Bowland Fells. The Howgill Fells and Orton Fells in Cumbria are also sometimes seen as Pennine spurs. The Pennines are very important for collecting water, with many reservoirs in the upper parts of the river valleys.

Most of the Pennines are protected as national parks or Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONBs). From north to south, including the Cheviots, the range is part of Northumberland National Park, the North Pennines AONB, the Yorkshire Dales National Park, Nidderdale AONB, the Forest of Bowland AONB, and the Peak District National Park. The only large area not protected is between Skipton and Marsden.

Britain's oldest long-distance footpath, the 268-mile (429 km) Pennine Way, runs along most of the Pennines.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The name "Pennine" might come from an old British or Welsh word pen-, meaning "head" or "top." However, the name didn't become common until the 1700s. It most likely came from comparing these hills to the Apennine Mountains in Italy, which also run down the middle of that country.

Some people thought the name came from a book called The Description of Britain (Latin: De Situ Britanniæ). This book was actually a fake made in the 1740s, but people believed it was real for a long time. However, experts like George Redmonds found that people had been comparing the English hills to the Italian Apennines much earlier, even back in the 1500s. So, the fake book might have just made the name more popular.

Some towns and places in the Pennines have names from Celtic languages, like Penrith, Pen-y-ghent, Pendle Hill, the River Eden, and Cumbria. But more often, local names come from Anglo-Saxon and Norse (Viking) settlers. In Yorkshire and Cumbria, you can still hear many words from the Norse language that aren't common in standard English. For example, gill/ghyll means a narrow, steep valley, beck means a brook or stream, fell means a hill, and dale means a valley.

Pennine Geography

The northern Pennine range is next to the lower hills of the Lake District, and the uplands of the Howgill Fells, Orton Fells, Border Moors, and Cheviot Hills. The West Pennine Moors, Rossendale Valley, and Forest of Bowland are hills that stick out to the west. The first two are in the South Pennines. The Howgill Fells and Orton Fells are sometimes seen as part of the Pennines, and both are inside the Yorkshire Dales National Park. The Pennines are surrounded by large lowland areas like the Eden Valley, West Lancashire Coastal Plain, Cheshire Plain, Vale of York, Humberhead Levels, and the Midland Plains.

The Pennines begin at their southern end in the Peak District. Their southern foothills blend into the lowlands and river basin of the Trent Valley. This valley separates the Pennines from the Midland Plains to the south. The Pennines continue north from the Peak District and meet the South Pennines around the Tame Valley, Standedge, and Holme Valley. The South Pennines are separated from the Forest of Bowland by the Ribble Valley. They include the Rossendale Valley and West Pennine Moors in the west. The range then goes further north into the Aire Gap. This gap separates the Yorkshire Dales from the South Pennines to the south and the Forest of Bowland to the southwest. The main Pennine range then continues north across the Yorkshire Dales to the Stainmore Gap, where it meets the North Pennines. The range ends at its northern tip at the Tyne Gap. This gap separates it from the Border Moors and Cheviot Hills, which are across the Anglo-Scottish border.

Even though the Pennines cover the area between the Peak District and the Tyne Gap, the Pennine Way walking path can change how people think about where the Pennines start and end. The southern end of the Pennines is often said to be in the High Peak area of Derbyshire at Edale, which is where the Pennine Way begins. However, the range and its lower hills actually continue south across the Peak District to the Trent Valley, covering eastern Cheshire, northern and eastern Staffordshire, and southern Derbyshire. On the other hand, the Border Moors and Cheviot Hills, which are separated by the Tyne Gap and Whin Sill (where the A69 and Hadrian's Wall run), are not officially part of the Pennines. But because the Pennine Way crosses them, they are often thought of as being part of the range.

Most of the Pennine landscape has high moorland areas with more fertile river valleys cutting through them. However, the landscape changes in different parts. The Peak District has hills, flat areas (plateaus), and valleys. It's divided into the Dark Peak with its moorlands and rocky edges, and the White Peak with its limestone gorges. The South Pennines is an area of hills and moorlands with narrow valleys between the Peak District and Yorkshire Dales. Bowland has a central upland area with deep, rocky fells covered in heather, peat bogs, and steep, wooded valleys that connect the high and low lands. The landscape is higher and more like mountains in the Yorkshire Dales and North Pennines. The Yorkshire Dales are known for their valleys, moorlands, and fells, while the North Pennines have flat areas, moorlands, fells, rocky edges, and valleys. Most of the highest peaks are in the west.

How High Are the Pennines?

The Pennines are mostly fells (hills), with most of the mountainous parts in the north. The highest point is Cross Fell in eastern Cumbria, which is 2,930 feet (893 meters) high. Other main peaks in the North Pennines include Great Dun Fell (2,782 ft/848 m), Mickle Fell (2,585 ft/788 m), and Burnhope Seat (2,451 ft/747 m).

In the Yorkshire Dales, important peaks are Whernside (2,415 ft/736 m), Ingleborough (2,372 ft/723 m), High Seat (2,328 ft/710 m), Wild Boar Fell (2,324 ft/708 m), and Pen-y-ghent (2,274 ft/693 m). In the Forest of Bowland, main peaks include Ward's Stone (1,841 ft/561 m), Fair Snape Fell (1,710 ft/521 m), and Hawthornthwaite Fell (1,572 ft/479 m).

The land is lower towards the south. The only peaks over 2,000 feet (610 meters) are Kinder Scout (2,087 ft/636 m) and Bleaklow (2,077 ft/633 m) in the Peak District. Other important peaks in the South Pennines and Peak District include Black Hill (1,909 ft/582 m), Shining Tor (1,834 ft/559 m), Pendle Hill (1,827 ft/557 m), Black Chew Head (1,778 ft/542 m), Rombalds Moor (1,319 ft/402 m), and Winter Hill (1,496 ft/456 m).

Where Does the Water Go?

For most of their length, the Pennines act as the main watershed in northern England. This means they divide the rivers that flow west from those that flow east.

On the western side of the Pennines, rivers like the Eden, Ribble, Dane, and parts of the Mersey (including the Irwell, Tame, and Goyt) all flow west towards the Irish Sea.

On the eastern side, the rivers Tyne, Wear, and Tees flow directly into the North Sea. The Swale, Ure, Nidd, Wharfe, Aire, Calder, and Don all flow into the Yorkshire Ouse. They then reach the sea through the Humber Estuary.

The River Trent flows around the southern end of the Pennines and then northwards on the eastern side. It collects water from other rivers, mainly the Dove and Derwent. The Trent drains both the east and west sides of the southern Pennines and also reaches the North Sea through the Humber Estuary. The Trent and Ouse rivers meet at Trent Falls and flow into the Humber. A lot of water can flow through the Humber, sometimes as much as 1,500 cubic meters per second.

Pennine Climate

The Pennines generally have a mild oceanic climate (like the rest of England). However, the higher parts get more rain, stronger winds, and colder weather than the areas around them. Some of the highest places have a subpolar oceanic climate, which can be similar to a tundra climate in areas like Great Dun Fell.

More snow falls on the Pennines than on the lower areas nearby because of the height and distance from the coast. Unlike other parts of England, the Pennines can have quite harsh winters.

The northwest is one of the wettest parts of England, and much of that rain falls on the Pennines. The eastern side is drier than the west. This is because of a "rain shadow" effect, where the mountains block rainfall from reaching northeast England.

Rainfall is very important for the plants and animals in the area, as well as for the people. Many towns and cities are built along rivers that flow from the Pennines. In northwest England, there aren't many natural underground water sources, so reservoirs are used to store water.

Water has also shaped the limestone landscapes in the North Pennines, Yorkshire Dales, and Peak District. You can find gorges (deep valleys) and caves in the Yorkshire Dales and Peak District. In some areas, the rain has led to poor soils, which is partly why much of the range has moorland landscapes. In other places where the soil is better, there is lush green plant life.

For growing plants, the Pennines are in hardiness zones 7 and 8, as set by the USDA. Zone 8 is common across most of the UK, but zone 7 is the UK's coldest hardiness zone. The Pennines, Scottish Highlands, Southern Uplands, and Snowdonia are the only areas in the UK that are in zone 7.

| Climate data for Great Dun Fell, North Pennines WMO ID: 03227; coordinates 54°41′02″N 2°27′05″W / 54.68401°N 2.45132°W; elevation: 847 m (2,779 ft); 1991–2020 normals |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 1.6 (34.9) |

1.6 (34.9) |

2.8 (37.0) |

5.4 (41.7) |

8.6 (47.5) |

11.0 (51.8) |

12.5 (54.5) |

12.3 (54.1) |

10.1 (50.2) |

6.8 (44.2) |

4.0 (39.2) |

2.1 (35.8) |

6.6 (43.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −0.4 (31.3) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

0.6 (33.1) |

2.7 (36.9) |

5.6 (42.1) |

8.2 (46.8) |

10.0 (50.0) |

9.8 (49.6) |

7.8 (46.0) |

4.8 (40.6) |

2.1 (35.8) |

0.0 (32.0) |

4.2 (39.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −2.4 (27.7) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

0.0 (32.0) |

2.7 (36.9) |

5.5 (41.9) |

7.5 (45.5) |

7.4 (45.3) |

5.6 (42.1) |

2.8 (37.0) |

0.2 (32.4) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

1.9 (35.4) |

| Source: Met Office | |||||||||||||

Pennine Geology

The Pennines were formed from several rock layers that were pushed up into a large arch shape, called an anticline, running north to south. The North Pennines are on something called the Alston Block, and the Yorkshire Dales are on the Askrigg Block. In the south, the Peak District is basically a flat-topped dome.

Each of these areas is made of Carboniferous limestone with a layer of Millstone Grit on top. The limestone can be seen on the surface in the North Pennines, Yorkshire Dales, and the Peak District. In the Dales and the White Peak, where limestone is exposed, large cave systems and underground rivers have formed. In the Dales, these caves are sometimes called "pots" in the local language. They include some of England's biggest caves, like Gaping Gill, which is over 350 feet (107 meters) deep, and Rowten Pot, which is 365 feet (111 meters) deep. Titan in the Peak District is the deepest shaft known in Britain. It connects to Peak Cavern in Castleton, Derbyshire, which has the largest cave entrance in the country. The wearing away of the limestone has also created cool rock formations, like the limestone pavements at Malham Cove.

Between the northern and southern areas of exposed limestone, from Skipton to the Dark Peak, there's a band of exposed gritstone. Here, the shales and sandstones of the Millstone Grit form high hills covered in moorland. This moorland is covered with bracken, peat, heather, and rough grasses. This higher ground is not good for farming and is barely suitable for grazing animals.

Pennine History

The Pennines were home to people during the Bronze Age, and there's also proof of Neolithic (New Stone Age) settlements. These include many stone circles and henges, like Long Meg and Her Daughters.

During Roman times, the uplands were controlled by the Brigantes, a group of tribes who lived in the area and worked together for defense. The Romans took over and used the Pennines for their natural resources, including the wild animals.

The Pennines were a challenge for the Anglo-Saxons as they moved west, though it seems they traveled through the valleys. During the Dark Ages, Celtic and Anglo-Saxon kingdoms controlled the Pennines. It's thought that the northern Pennines were part of the kingdom of Rheged.

During the Viking Age, Viking Danes settled in the east of the Pennines, and Norwegian Vikings settled in the west. The Vikings influenced place names, culture, and even the genes of the people living there. When England became one country, the Pennines were included. The mix of Celtic, Anglo-Saxon, and Viking heritage was similar to much of the rest of northern England, and its culture grew alongside its lowland neighbors. The Pennines were not a separate country but were divided among the nearby counties in northeast and northwest England. A big part of the Pennines was in the West Riding of Yorkshire.

Who Lives in the Pennines?

The Pennine region doesn't have many people living in it compared to other parts of England. Larger towns and cities are found in the lower hills and flat areas around the southern Pennine range. These include Barnsley, Chesterfield, Halifax, Huddersfield, Macclesfield, Oldham, Bury, Rochdale, Middleton, and Stockport. However, most of the northern Pennine range has very few people living there. The cities of Bradford, Derby, Leeds, Manchester, Sheffield, Stoke-on-Trent, and Wakefield are also in the surrounding lower hills and flatlands.

Pennine Economy

The main ways people make a living in the Pennines include sheep farming, quarrying (digging for stone), finance, and tourism. In the Peak District, tourism is the biggest job provider for people living in the park (24%). Manufacturing (making things) (19%) and quarrying (12%) are also important. About 12% of people work in agriculture (farming).

Limestone is the most important mineral dug up, mainly used for roads and cement. Other materials extracted include shale for cement and gritstone for building stone. The natural springs at Buxton and Ashbourne are used to produce bottled mineral water. There are also about 2,700 farms in the National Park. The South Pennines are mostly industrial, with main industries like textiles (making fabric), quarrying, and mining. Other economic activities in the South Pennines include tourism and farming.

Although the Forest of Bowland is mostly rural, the main economic activities there are farming and tourism. In the Yorkshire Dales, tourism brings in £350 million every year. Most jobs are in farming, hotels, and food services. There are also big challenges in managing tourism, farming, and other developments within the National Park. The main economic activities in the North Pennines are tourism, farming, timber (wood), and small-scale quarrying, because of the rural landscape.

Getting Around the Pennines

There are gaps that allow people to travel from west to east across the Pennines. The Tyne Gap, between the Pennines and the Cheviots, is one such gap. The A69 road and Tyne Valley railway use this gap to connect Carlisle and Newcastle upon Tyne. The A66 road, which reaches 1,450 feet (442 meters) at its highest point, follows an old Roman road. It goes from Scotch Corner to Penrith through the Stainmore Gap, connecting the Eden Valley in Cumbria and Teesdale in County Durham. The Aire Gap links Lancashire and Yorkshire through the valleys of the Aire and Ribble. Other high roads include Buttertubs Pass, named after limestone potholes near its 1,729-foot (527-meter) summit, between Hawes in Wensleydale and Swaledale. The A684 road from Sedbergh to Hawes via Garsdale Head reaches 1,100 feet (335 meters).

Further south, the A58 road crosses the Calder Valley between West Yorkshire and Greater Manchester, reaching 1,282 feet (391 meters) between Littleborough and Ripponden. The A646 road along the Calder Valley between Burnley and Halifax reaches 764 feet (233 meters) by following the valley floors. In the Peak District, the A628 Woodhead road connects the M67 motorway in Greater Manchester with the M1 motorway in South Yorkshire. Holme Moss is crossed by the A6024 road, whose highest point is near Holme Moss transmitting station between Longdendale and Holmfirth.

The Pennines are also crossed by the M62 motorway, which is the highest motorway in England at 1,221 feet (372 meters) on Windy Hill near Junction 23.

Three canals, built during the Industrial Revolution, also cross the Pennines:

- The Huddersfield Narrow Canal connects Huddersfield in the east with Manchester in the west. When it reaches Marsden, it goes under the hills through the Standedge Tunnel to Diggle. You can even take a public narrowboat through the tunnel during the summer!

- The Rochdale Canal crosses the Pennines via Rochdale, connecting the town of Sowerby Bridge with Manchester.

- The Leeds and Liverpool Canal, which is the longest and most northern, crosses the Pennines via Skipton, Burnley, Chorley, and Wigan. It connects Leeds in the east with Liverpool in the west.

The first of three Woodhead Tunnels was finished in 1845 for the Sheffield, Ashton-Under-Lyne and Manchester Railway. It was one of the world's longest railway tunnels at 3 miles 13 yards (4,840 meters) when it was built. It was the first of several tunnels that crossed the Pennines, including the Standedge and Totley tunnels, which are only a little longer. The first two Woodhead tunnels were replaced by Woodhead 3, which was longer at 3 miles 66 yards (4,860 meters). It was built for electric trains and finished in 1953. This tunnel was opened by the transport minister Alan Lennox-Boyd on June 3, 1954. The railway line was closed in 1981.

The London and North Western Railway bought the Huddersfield and Manchester Railway in 1847. They built a single-line tunnel next to the canal tunnel at Standedge, which was 3 miles, 57 yards (4,803 meters) long. Today, train services along the Huddersfield line between Huddersfield and Victoria and Piccadilly stations in Manchester are run by TransPennine Express and Northern. Between 1869 and 1876, the Midland Railway built the Settle-Carlisle Line through remote, beautiful parts of the Pennines. It goes from near Settle to Carlisle, passing Appleby-in-Westmorland and other towns. This line has survived, even through tough times, and is now run by Northern Rail.

The Trans Pennine Trail is a long path for cyclists, horse riders, and walkers. It runs from west to east alongside rivers and canals, along old railway tracks, and through historic towns and cities. It stretches from Southport to Hornsea (207 miles/333 km). It crosses the north-south Pennine Way (268 miles/431 km) at Crowden-in-Longdendale.

National Parks and Protected Areas

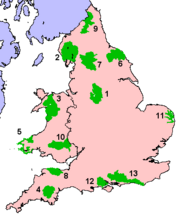

Large parts of the Pennines are protected as UK national parks and Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONBs). AONBs have almost the same level of protection as national parks. The national parks within the Pennines are the Yorkshire Dales National Park (marked 7 on the map) and the Peak District National Park (marked 1).

The North Pennines AONB, which is just north of the Yorkshire Dales, is almost as big as a national park. It includes some of the highest peaks in the Pennines and its most isolated and least populated areas. Other AONBs are Nidderdale, which is east of the Yorkshire Dales, and the Bowland Fells, which includes Pendle Hill, west of the Yorkshire Dales.

Pennine Languages

The language spoken in the Pennines before and during Roman times was Common Brittonic. In the Early Middle Ages, the Cumbric language developed. We don't have much evidence of Cumbric, so it's hard to know if it was different from Old Welsh. We also don't know exactly how far the Cumbric language was spoken.

During Anglo-Saxon times, the area was settled by Anglian people from Mercia and Northumbria, rather than the Saxon people from Southern England. Celtic speech stayed in most parts of the Pennines longer than it did in the surrounding areas of England. Eventually, the Celtic language of the Pennines was replaced by early English as Anglo-Saxons and Vikings settled the area and mixed with the Celts.

During the Viking Age, Scandinavian settlers brought their language, Old Norse. The mixing of Norse and Old English was important in forming Middle English and later Modern English. Many individual words from Norse are still used in local ways of speaking, like the Yorkshire dialect, and in local place names.

Pennine Folklore and Customs

The folklore and customs in the Pennines are mostly based on Celtic, Anglo-Saxon, and Viking traditions. Many customs and stories come from old pagan traditions that later became part of Christian beliefs. In the Peak District, a well-known custom is well dressing. This tradition started with pagan beliefs and later became Christian.

Pennine Plants (Flora)

Plants in the higher Pennines are suited to moorland and cold, subarctic landscapes and climates. The plants found there can also be seen in other moorland areas in Northern Europe, and some species are also found in areas of tundra. In the Pennine gritstone areas above 900 feet (274 meters), the topsoil is very acidic (pH 2 to 4). This means only plants like bracken, heather, sphagnum moss, and rough grasses like cottongrass, purple moor grass, and heath rush can grow there.

When the Ice age glaciers melted around 11,500 BC, trees returned. Scientists can study ancient pollen to find out what kinds of trees grew. The first trees to grow were willow, birch, and juniper, followed later by alder and pine. By 6500 BC, temperatures were warmer, and woodlands covered 90% of the dales, mostly with pine, elm, lime, and oak trees. On limestone soils, oak trees grew more slowly, and pine and birch were more common. Around 3000 BC, there was a clear drop in tree pollen, which shows that early farmers were clearing woodlands to create more grazing land for their animals. Studies at Linton Mires and Eshton Tarn show an increase in grassland plants. In areas with poor drainage, like those with gritstone, shale, or clay, the topsoil gets waterlogged in winter and spring. Here, fewer trees combined with heavy rainfall lead to blanket bogs that can be up to 2 meters (6.6 feet) thick. Even today, when peat erodes, you can still see the stumps of these ancient trees.

"In digging it away they frequently find vast fir trees, perfectly sound, and some oaks ..."

—Arthur Young, A Six Months' Tour of the North of England (1770)

Limestone areas of the Pennines, such as the White Peak, Yorkshire Dales, and Upper Teesdale, have been named nature reserves or Important Plant Areas by the plant conservation group Plantlife. These areas are very important nationally for their wildflowers.

Pennine Animals (Fauna)

The animals in the Pennines are similar to those in the rest of England and Wales, but the area is home to some special species. Deer are found throughout the Pennines. Some animal species that are rare elsewhere in England can be found here. Arctic hares, which were common in Britain during the Ice Age, moved to the cooler, more tundra-like uplands when the climate warmed up. They were brought to the Dark Peak area of the Peak District in the 1800s.

Large areas of heather moorland in the Pennines are managed for hunting wild red grouse. The related black grouse, which is declining in numbers, can still be found in the northern parts of the Pennines. Other birds whose main breeding grounds in England are in the Pennines include golden plover, snipe, curlew, dunlin, merlin, short-eared owl, ring ouzel, and twite. Many of these birds are at the southern edge of where they usually live and are more common in Scotland.

See also

In Spanish: Peninos para niños

In Spanish: Peninos para niños

- Geography of England

- Geology of Great Britain

- Geology of Yorkshire

- North Pennines

- South Pennines

- Yorkshire Three Peaks

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |