Ice sheet facts for kids

Imagine a huge blanket of ice covering a whole country! That's what an ice sheet is. It's also called a continental glacier. These are massive layers of ice that spread over land and are bigger than 50,000 km2 (19,000 sq mi). Right now, Earth has two main ice sheets: the Antarctic ice sheet and the Greenland ice sheet. They are much larger than smaller ice formations like ice caps or mountain glaciers. An ice cap is a smaller version, covering less than 50,000 km2.

Even though the top of an ice sheet is very cold, the bottom can be warmer because of heat from deep inside the Earth. This warmth can melt some of the ice at the base. This meltwater acts like a lubricant, helping the giant ice sheet slide and flow faster. These fast-moving parts are called ice streams.

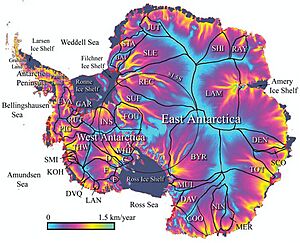

Ice sheets are always moving, even if it's slowly. The ice flows outwards from the highest point in the middle, called the central plateau, towards its edges. The slope is gentle in the middle but gets much steeper near the edges.

Scientists are studying how rising global temperatures affect ice sheets. While it takes a very long time for air temperature changes to reach the bottom of the ice, increased melting on the surface can create supraglacial lakes. These lakes can send warm water down to the base of the glacier, making it move faster.

Long, long ago, during past ice ages, Earth had many more ice sheets. For example, during the Last Glacial Period, a huge ice sheet called the Laurentide Ice Sheet covered much of North America. Another one, the Weichselian ice sheet, covered Northern Europe.

Contents

What Are Ice Sheets?

An ice sheet is a giant body of ice that covers a land area the size of a continent. This means it's larger than 50,000 square kilometers. The two ice sheets we have today, in Greenland and Antarctica, are much, much bigger. The Greenland ice sheet is about 1.7 million km2, and the Antarctic ice sheet is a massive 14 million km2!

These ice sheets are also incredibly thick. They are made of a continuous layer of ice, averaging about 2 km (1.2 mi) thick. This happens because most of the snow that falls on them never melts. Instead, new layers of snow keep falling and pressing down on the old snow, turning it into solid ice over time.

This process of ice growing still happens today. For example, during World War II, a Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighter plane crashed in Greenland in 1942. When it was found 50 years later, it was buried under 81 meters (268 feet) of ice that had formed since the crash!

How Ice Sheets Move

The Flow of Glaciers

Ice sheets are always moving, even if it's very slowly. The ice gradually flows outwards from the highest point in the center, called the central plateau. It moves towards the edges of the ice sheet. The slope of the ice is gentle in the middle but gets much steeper at the edges. This happens because a lot of snow builds up in the center, while less snow falls and more ice melts at the edges.

This movement is mainly caused by gravity, pulling the heavy ice downhill. How fast the ice moves depends on its temperature and the strength of the ground underneath it. Sometimes, ice sheets can have sudden bursts of faster movement, followed by longer quiet periods. These changes can happen over hours or even thousands of years.

For example, the ocean's tides can affect how ice moves near the coast. A 1-meter change in tide can be felt as far as 100 km inland! During very high tides, an ice stream might stop for a few hours, then suddenly surge forward about a foot in less than an hour.

Rising global air temperatures from climate change can also affect how ice sheets move. While it takes about 10,000 years for air temperature changes to directly warm the very bottom of the ice, increased melting on the surface is a faster way to have an impact. This surface melting creates more supraglacial lakes. These lakes can send warm water down to the base of the glacier, making it slide faster. If a lake is large enough, its water can create a crack all the way to the bottom of the glacier. When this happens, all the warm lake water can reach the base in just a few hours, lubricating the ground and causing the glacier to surge forward.

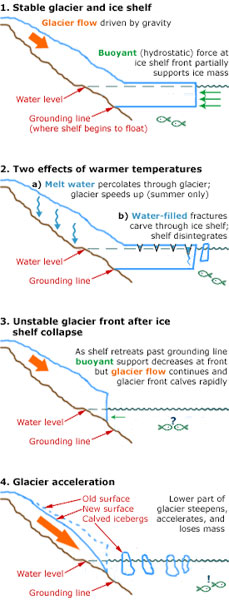

The Role of Ice Shelves

At the edges of ice sheets that meet the ocean, extra ice flows out through fast-moving ice streams or outlet glaciers. This ice either falls directly into the sea or forms floating ice shelves. These ice shelves are like extensions of the ice sheet that float on the water. They then break off icebergs at their outer edges. Ice shelves can also melt from underneath, especially in places like Antarctica, where warm ocean currents flow beneath them.

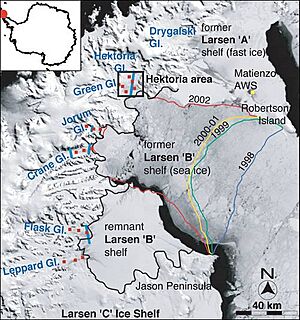

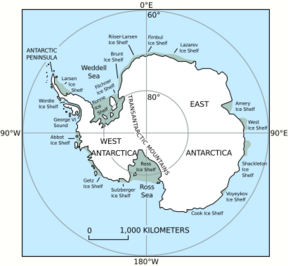

Ice shelves are very important because they act like a brake, holding back the main ice sheet behind them. When an ice shelf breaks apart, the glaciers behind it can start to flow much faster. For instance, when the Larsen B ice shelf in Antarctica collapsed in 2002, four glaciers behind it sped up significantly. This shows how important ice shelves are for keeping the larger ice sheets stable.

Why Ice Sheets Can Become Unstable

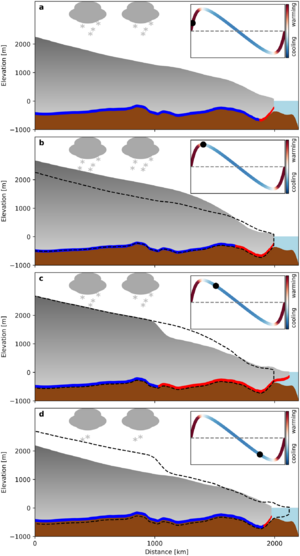

Marine Ice Sheet Instability (MISI)

Scientists have studied a process called Marine Ice Sheet Instability (MISI). This idea suggests that ice sheets that are grounded (resting) below sea level can become less stable as they melt. This is because seawater is heavier than ice. If the ice sheet gets thinner, the water can push into gaps at its base, making the ice sheet float more and retreat faster.

However, MISI is less likely to happen if there's a stable ice shelf in front of the ice sheet. The point where the ice sheet touches the ground, called the grounding line, is especially stable if it's in a protected bay. But if warm ocean water melts the ice shelf from below, the shelf gets thinner. A thinner ice shelf provides less support to the ice sheet, allowing the grounding line to move backward. This can create a cycle where the ice sheet loses more ice, becomes lighter, and retreats even further.

Some parts of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet are grounded below sea level, making them vulnerable to this kind of rapid ice loss. The Thwaites and Pine Island glaciers, for example, have been thinning and speeding up in recent decades. This could lead to a faster rise in sea level.

Marine Ice Cliff Instability (MICI)

Another idea is Marine Ice Cliff Instability (MICI). This suggests that very tall ice cliffs (over 90 meters or 300 feet above water) might collapse under their own weight once the ice that supports them from the front is gone. This collapse could then expose more ice cliffs, leading to a rapid chain reaction of breaking ice and a fast rise in sea level.

This theory has been very influential, but it's also been debated by scientists. Some research suggests that past sea level rises could be explained without MICI. Other studies indicate that if MICI happens, the broken ice debris could build up and slow down the process. Scientists are still working to understand exactly how much this type of instability might contribute to future sea level rise.

Earth's Current Giant Ice Sheets

If all the ice sheets and glaciers on Earth were to melt completely, it would take thousands of years. But it would cause sea levels to rise by about 216 ft (66 m)! (Remember, melting sea ice and floating ice shelves don't raise sea levels because they are already in the water, like an ice cube melting in a glass.)

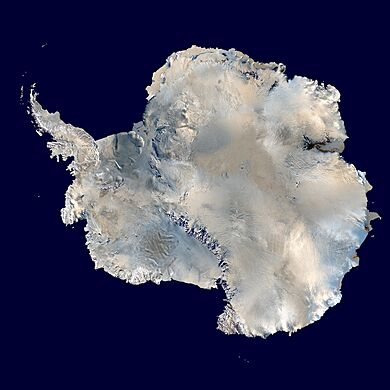

Antarctic Ice Sheet

The Antarctic ice sheet is the largest single mass of ice on Earth. It covers about 98% of the continent of Antarctica. This massive ice sheet holds enough ice to raise global sea levels by about 58 meters if it all melted. It's divided into two main parts: the East Antarctic Ice Sheet and the West Antarctic Ice Sheet.

East Antarctic Ice Sheet

Quick facts for kids East Antarctic Ice Sheet |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Type | Ice sheet |

| Thickness | ~2.2 km (1.4 mi) (average), ~4.9 km (3.0 mi) (maximum) |

The East Antarctic Ice Sheet is the largest part of the Antarctic ice sheet. It's also the thickest, with an average thickness of about 2.2 kilometers (1.4 miles) and a maximum thickness of nearly 5 kilometers (3.1 miles)! It's generally considered more stable than the West Antarctic Ice Sheet.

West Antarctic Ice Sheet

| West Antarctic Ice Sheet | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Type | Ice sheet |

| Area | <1,970,000 km2 (760,000 sq mi) |

| Thickness | ~1.05 km (0.7 mi) (average), ~2 km (1.2 mi) (maximum) |

| Status | Receding |

The West Antarctic Ice Sheet is smaller than the East Antarctic Ice Sheet, covering less than 1.97 million square kilometers. Its average thickness is about 1.05 kilometers (0.65 miles). A key difference is that much of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet rests on land that is below sea level, making it more vulnerable to melting from warm ocean waters. Scientists are closely watching this ice sheet because it has been losing mass and retreating in recent decades.

Greenland Ice Sheet

| Greenland ice sheet | |

|---|---|

| Grønlands indlandsis Sermersuaq |

|

|

|

| Type | Ice sheet |

| Coordinates | 76°42′N 41°12′W / 76.7°N 41.2°W |

| Area | 1,710,000 km2 (660,000 sq mi) |

| Length | 2,400 km (1,500 mi) |

| Width | 1,100 km (680 mi) |

| Thickness | 1.67 km (1.0 mi) (average), ~3.5 km (2.2 mi) (maximum) |

The Greenland ice sheet is the second-largest ice sheet on Earth. It covers about 80% of Greenland. It is about 1.71 million square kilometers in area, 2,400 km (1,500 mi) long, and 1,100 km (680 mi) wide. Its average thickness is about 1.67 kilometers (1.04 miles), but it can be as thick as 3.5 kilometers (2.2 miles) in some places. If the Greenland ice sheet were to melt completely, it would raise global sea levels by about 7.4 meters.

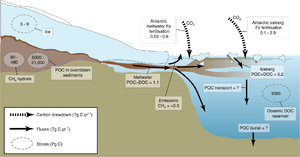

Ice Sheets and the Carbon Cycle

For a long time, scientists thought ice sheets didn't play a big role in the Earth's carbon cycle. But recent research shows that they are actually very important! Ice sheets contain unique tiny living things (microbes) and can store huge amounts of carbon. More than 100 billion tonnes of organic carbon are stored within and under ice sheets.

There's a big difference in how much carbon is stored under the two main ice sheets. The Greenland ice sheet has about 0.5 to 27 billion tonnes of carbon underneath it. But the Antarctic ice sheet is thought to have a massive 6,000 to 21,000 billion tonnes of carbon stored below it!

This stored carbon can affect climate change. If it's released gradually into the atmosphere as ice melts, it can increase carbon dioxide emissions. To give you an idea, the Arctic permafrost (frozen ground) holds about 1,400 to 1,650 billion tonnes of carbon. Humans currently release about 40 billion tonnes of CO2 each year.

In Greenland, at a place called Russell Glacier, meltwater releases carbon into the air as methane. Methane is a powerful greenhouse gas. However, there are also many bacteria there that eat methane, which helps to limit these emissions.

Ice Sheets Through Earth's History

The Earth's climate has changed many times over millions of years, causing ice ages and warmer periods. These changes are often linked to Milankovitch cycles. These are natural patterns in how much sunlight reaches Earth, caused by small changes in Earth's orbit and tilt as it moves around the Sun.

For example, over the last 100,000 years, parts of the huge Laurentide Ice Sheet in North America broke off. This sent giant icebergs floating into the North Atlantic Ocean. As these icebergs melted, they dropped rocks and boulders they carried from the land, leaving layers of debris on the seafloor. These events are called Heinrich events. They seem to happen every 7,000 to 10,000 years during cold periods.

Scientists think these events might be caused by the ice sheet growing to an unstable size, then parts of it collapsing. Other factors, like sudden warmings in the Northern Hemisphere called Dansgaard–Oeschger events, also played a role. These events show that ice sheets have always been dynamic, changing and shaping our planet over vast stretches of time.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Indlandsis para niños

In Spanish: Indlandsis para niños

- Cryosphere

- Ice planet

- Quaternary glaciation

- Snowball Earth

- Wisconsin glaciation

- Ice-sheet model

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |