Cumbric facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Cumbric |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Northern England & Southern Scotland | |||

| Extinct | 12th century | |||

| Language family | ||||

| Linguist List | xcb | |||

|

||||

Cumbric was an old language spoken a long time ago, during the Early Middle Ages. It was used in a part of Britain called the Hen Ogledd, or "Old North." This area is now parts of northern England (like Westmorland, Cumberland, and northern Lancashire) and southern Scotland.

Cumbric was very similar to Old Welsh and other Brittonic languages. Some old place names suggest it might have been spoken even further south, in places like Pendle and the Yorkshire Dales. Most experts believe Cumbric died out in the 12th century. This happened after the Kingdom of Strathclyde, where Cumbric was spoken, became part of the Kingdom of Scotland.

Contents

What People Called It

It can be tricky to talk about the Cumbric language and the people who spoke it. The people themselves probably called themselves *Cumbri. This is similar to how the Welsh people called themselves Cymry. Both words likely mean "fellow countrymen." This suggests that the Welsh and the Cumbric speakers probably felt they were part of the same group.

Other groups had different names for them. Old Irish speakers called them "Britons." The Norse people called them Brettar. In Latin, the names Cymry (for Welsh) and Cumbri (for Cumbric) became Cambria and Cumbria. Later, in Scots, a Cumbric speaker might have been called Wallace, which comes from a word meaning "Welsh."

One old Latin text from around 1200 says:

In Cumbria itaque: regione quadam inter Angliam et Scotiam sita – "And so in Cumbria: a region situated between England and Scotland".

Experts like John T. Koch and Kenneth H. Jackson have tried to define the area where Cumbric was spoken. It was generally between the River Mersey in the south and the Firth of Clyde in the north. Its eastern border was the Southern Scottish Uplands and the Pennine Ridge.

How We Know About Cumbric

We don't have any actual books or writings in Cumbric. Most of what we know comes from other sources. The best evidence is from the names of places in northern England and southern Scotland. We also find clues in the names of people from Strathclyde in old Scottish, Irish, and Anglo-Saxon records. A few Cumbric words even survived as legal terms in southwest Scotland.

Even though the language is gone, some traces of its words might still exist today. This includes old "counting scores" (like "Yan tan tethera") and a few local dialect words.

From this limited evidence, we can't learn much about Cumbric's unique features. We don't even know what its speakers called it. However, linguists generally agree that Cumbric was a Western Brittonic language. It was closely related to Welsh and, less closely, to Cornish and Breton.

Around the year 600, the original Common Brittonic language started to split into different languages. These included Cumbric in northern Britain, Old Welsh in Wales, and Southwestern Brittonic (which became Cornish and Breton).

Place Names

Many place names in southern Scotland (south of the Forth and Clyde rivers) and northern England come from Cumbric. They are common in the historic county of Cumberland and nearby parts of Northumberland. Some are also found in Lancashire and North Yorkshire.

Some major towns and cities in the region have names that came from Cumbric:

- Bathgate, West Lothian: This means 'boar wood' (like Welsh baedd 'wild boar' + coed 'forest, wood').

- Carlisle, Cumbria: The Romans called it Luguvalium. The word caer 'fort' was added later.

- Glasgow, Scotland: Many believe this name comes from words like Welsh glas gau, meaning 'green hollow'.

- Lanark, Lanarkshire: This is like the Welsh word llannerch, meaning 'glade' or 'clearing'.

- Penicuik, Midlothian: This name means 'hill of the cuckoo' (like Welsh pen y gog).

- Penrith, Cumbria: This means 'chief ford' (Welsh pen 'head, chief' + rhyd 'ford').

Many Cumbric elements appear again and again in place names. Here are some examples, compared to their modern Welsh equivalents:

| Element (Welsh) | Celtic root | Meaning | Place names |

|---|---|---|---|

| blaen | *blagno- | end, point, summit; source of river | Blencathra, Blencogow, Blindcrake, Blencarn, Blennerhassett |

| caer | castrum (Latin) | fort, stronghold; wall, rampart | Carlisle, Cardew, Cardurnock, Carfrae, Cargo, Carlanrig, Carriden, Castle Carrock, Cathcart, Caerlaverock, Cardonald, Cramond, Carleith |

| coed | *keto- | trees, forest, wood | Bathgate, Dalkeith, Culgaith, Tulketh, Culcheth, Pencaitland, Penketh, Towcett, Dankeith, Culgaith, Cheadle, Cheetham, Cathcart, Cheetwood, Cathpair, Kincaid, Inchkeith |

| cwm | *kumba- | deep narrow valley; hollow, bowl-shaped depression | Cumrew, Cumwhitton, Cumwhinton, Cumdivock |

| drum, trum | *drosman- | ridge | Drumlanrig, Dundraw, Mindrum, Drumburgh, Drem, Drumaben |

| eglwys | ecclesia (Latin) | church | Ecclefechan, Ecclesmachan, Eccleston, Eccles, Terregles, Egglescliffe, Eggleshope, Ecclaw, Ecclerigg, Dalreagle, Eggleston, possibly Eaglesfield |

| llannerch | *landa- | clearing, glade | Barlanark, Carlanrig, Drumlanrig, Lanark[shire], Lanercost |

| moel | *mailo- | bald; (bare) mountain/hill, summit | Mellor, Melrose, Mallerstang |

| pen | *penno- | head; top, summit; source of stream; headland; chief, principal | Pennygant Hill, Pen-y-Ghent, Penrith, Penruddock, Pencaitland, Penicuik, Penpont, Penketh, Pendle, Penshaw, Pemberton, Penistone, Pen-bal Crag, Penwortham, Torpenhow |

| pren | *prenna- | tree; timber; cross | Traprain Law, Barnbougle, Pirn, Pirncader, Pirniehall, Pirny Braes, Primrose, Prendwick |

| tref | *trebo- | town, homestead, estate, township | Longniddry, Niddrie, Ochiltree, Soutra, Terregles, Trabroun, Trailtrow, Tranent, Traprain Law, Traquair, Treales, Triermain, Trostrie, Troughend, Tranew; possibly Bawtry, Trafford |

Sometimes, Cumbric names were replaced by Scottish Gaelic, Middle English, or Scots names. For example:

- Edinburgh was called Din Eidyn in old Welsh texts. This means 'fort of Eidyn'.

- Falkirk used to be called Eglesbreth, meaning 'speckled church' in Cumbric.

- Kinneil comes from a Gaelic name meaning 'head of the [Antonine] Wall'. But it was also recorded with a Cumbric name, Penguaul.

Counting Systems

One interesting clue about Cumbric is a group of counting systems found in northern England. These are often called "sheep-counting numerals," but they were used for other things too, like knitting or children's games. Around 100 of these systems have been found since the 1700s. Experts agree they come from a Brittonic language, similar to Welsh.

Many people think these counting systems are a leftover from medieval Cumbric. While some scholars have debated this, it's still a good possibility.

Like other Brittonic languages, Cumbric used a vigesimal counting system. This means it counted in groups of twenty. So, after ten, numbers would be "one-and-ten," "two-and-ten," and so on, up to fifteen. Then it would be "one-and-fifteen," "two-and-fifteen," up to twenty. The words for the numbers themselves changed a lot from place to place.

| Nr. | Keswick | Westmorland | Eskdale | Millom | High Furness | Wasdale | Teesdale | Swaledale | Wensleydale | Ayrshire | Modern Welsh | Modern Cornish | Modern Breton |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | yan | yan | yaena | aina | yan | yan | yan | yahn | yan | yinty | un | onan, unn | unan |

| 2 | tyan | tyan | taena | peina | taen | taen | tean | tayhn | tean | tinty | dau m, dwy f | dew m, diw f | daou m, div f |

| 3 | tethera | tetherie | teddera | para | tedderte | tudder | tetherma | tether | tither | tetheri | tri m, tair f' | tri m, teyr f | tri m, ter f |

| 4 | methera | peddera | meddera | pedera | medderte | anudder | metherma | mether | mither | metheri | pedwar m, pedair f | peswar m, peder f | pevar m, peder f |

| 5 | ... | gip | ... | ... | ... | nimph | pip | mimp[h] | pip | bamf | pump | pymp | pemp |

| 6 | sethera | teezie | hofa | ithy | haata |

|

lezar | hith-her | teaser | leetera | chwech | hwegh | c'hwec'h |

| 7 | lethera | mithy | lofa | mithy | slaata |

|

azar | lith-her | leaser | seetera | saith | seyth | seizh |

| 8 | hovera | katra | seckera | owera | lowera |

|

catrah | anver | catra | over | wyth | eth | eizh |

| 9 | dovera | hornie | leckera | lowera | dowa |

|

horna | danver | horna | dover | naw | naw | nav |

| 10 | dick | dick | dec | dig | dick |

|

dick | dic | dick | dik | deg | deg | dek |

| 15 | bumfit | bumfit | bumfit | bumfit | mimph |

|

bumfit | mimphit | bumper |

|

pymtheg | pymthek | pemzek |

| 20 | giggot |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

jiggit |

|

ugain | ugens | ugent |

Words in Scots and English

Some words in the Scots language and Northern English dialects might have come from Cumbric. It's hard to be sure because Brittonic and Goidelic languages (like Gaelic) have similar words. Also, words were borrowed back and forth between these languages.

Here are a few words that might have Cumbric roots:

- Brat – means 'apron'. It's in Welsh, Scots, and northern English.

- Coble – a small, flat-bottomed boat. Similar to the Welsh word ceubal meaning 'a hollow'.

- Crag – means 'rocks'. This could come from Brittonic (like Welsh craig) or Goidelic (like Scottish Gaelic creag).

- Croot – means 'small boy' (like Welsh crwt).

- Croude – a small harp or lyre (like Welsh crwth).

- Lum – a Scottish word for 'chimney' (like Middle Welsh llumon).

Cumbric and Old Welsh

Linguists aren't completely sure if Cumbric was its own language or just a different way of speaking Old Welsh. It's called "Cumbric" because it was spoken in a specific area. Experts like John Koch and Kenneth Jackson have called it a dialect. However, they also noted that some Cumbric place names look like they came from a developed language, much like Welsh, Cornish, or Breton.

One interesting feature is the use of the element Gos- or Cos- in personal names. This means 'servant of' and is followed by a saint's name. For example, Gospatric means 'servant of Saint Patrick'. Other names include Gosmungo (servant of Saint Mungo) and Goscuthbert (servant of Cuthbert). This is similar to Gaelic names like Malcolm (meaning 'servant of Columba').

Another difference might be how the definite article (like "the") was used. In Welsh, it's yr, -'r, y. In Cumbric, there's evidence for an article like -n as well as -r. For example:

- Tallentire, Cumbria: 'brow/end of the land' (Welsh tal y tir).

- Pen-y-Ghent, Yorkshire: 'hill of the border country' (Welsh pen y gaint).

Also, some Cumbric names like Carlisle and Derwent don't have the -ydd ending that their Welsh equivalents (Caerliwelydd and Derwennydd) do. This might show an early difference between Cumbric and Welsh.

When Did Cumbric Disappear?

It's hard to say exactly when Cumbric died out. But we have some clues that help us guess.

In the mid-1000s, some landowners in the area still had Cumbric names. For example, Dunegal and Moryn. A village near Carlisle, Cumwhitton, has a name that mixes a Cumbric word (like Welsh cwm, meaning valley) with a Norman name, Quinton. Normans didn't arrive there until after 1069.

At the Battle of the Standard in 1138, the Cumbrians were still seen as a separate group. Since their way of life was similar to their neighbors, their language might have been what made them different. Also, Castle Carrock was built around 1160–1170, and its name, Castell Caerog, is Cumbric.

The surname Wallace is another clue. It means "Welshman." While some Wallaces might have come from Wales, it's also very likely that the name referred to local Cumbric-speaking people. Sir William Wallace, a famous Scottish hero, came from an area with Cumbric names (Renfrew and Lanark). Even if his family had the surname for a while, it suggests they might have spoken Cumbric not long before.

Even Scottish kings recognized the Cumbrians as a separate group. David I was called "Prince of the Cumbrians" before he became king in 1124. Later, William the Lion also spoke to the Cumbrians as a distinct group between 1173 and 1180.

However, by the late 1100s, legal documents show that the upper classes in the Lanercost area had English or Norman French names, not Cumbric ones. In 1262, in Peebles, most jury members also had English or Norman names. But a few names, like Gauri Pluchan and Robert Gladhoc, might still show Cumbric traces.

It's common for the upper classes to stop speaking an old language before the common people do. So, it's possible that ordinary people continued to speak Cumbric for a while longer. Around 1200, a list of men's names from Peebles included Cumbric names like Gospatrick and Gosmungo.

The royal seal of Alexander III of Scotland (who ruled from 1241–1286) called him "King of Scots and Britons." In 1305, Edward I of England banned the Leges inter Brettos et Scottos (Laws between Britons and Scots). Here, "Britons" referred to the Cumbric-speaking people of southern Scotland and northern England.

Based on all this, Cumbric likely survived as a community language until the mid-1100s. It might have even lasted into the 1200s with the very last speakers. If the names from 1262 do show Cumbric, then the language probably died out completely between 1250 and 1300 at the latest.

See also

- Cumbrian dialect

- Cumbrian toponymy

- Kenneth H. Jackson

- Kingdom of Strathclyde

Images for kids

-

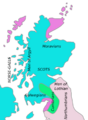

Linguistic division in early twelfth century Scotland. Gaelic speaking Norse-Gaelic zone English-speaking zone Cumbric zone

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |