Merlin (bird) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Merlin |

|

|---|---|

|

|

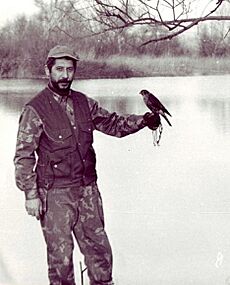

| A male prairie merlin with its prey in Alberta (Canada) | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Falconiformes |

| Family: | Falconidae |

| Genus: | Falco |

| Species: |

F. columbarius

|

| Binomial name | |

| Falco columbarius Linnaeus, 1758

|

|

| Subspecies | |

|

3–9 subspecies (see text) |

|

|

|

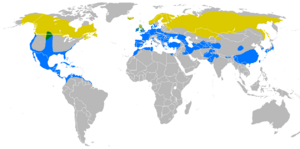

| Where Merlins live: Summer only Year-round Winter only | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Aesalon columbarius (Linnaeus, 1758) |

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The merlin (Falco columbarius) is a small falcon found in the Northern Hemisphere. It lives in many places across North America and Eurasia. This bird of prey was once called a pigeon hawk in North America. Merlins breed in the northern parts of the world. Some of them migrate to warmer areas in winter.

Male merlins usually have wingspans of about 53 to 58 centimeters (21 to 23 inches). Females are a little bigger. Merlins are very fast flyers and skilled hunters. They mostly hunt small birds like sparrows and quail. For hundreds of years, people have used merlins in falconry, which is a sport where trained birds hunt. In recent years, the number of merlins in North America has grown a lot. Some merlins even live in cities and do not migrate anymore.

Contents

What's in a Name?

An English naturalist named Mark Catesby first described the merlin in his book, calling it the "pigeon hawk." This was in 1729. Later, in 1758, Carl Linnaeus gave the bird its scientific name, Falco columbarius. The name Falco comes from a Latin word meaning "sickle," which refers to the bird's curved claws. The name columbarius means "of doves" in Latin.

The name "merlin" comes from an old French word, esmerillon. It is not named after the wizard Merlin from the King Arthur stories. The wizard's name comes from a Welsh name, and it has no connection to the bird's name.

Merlin Family Tree

Scientists are still learning about how merlins are related to other falcons. Merlins look and act quite different from other falcons. Some studies suggest that merlins have been a separate group of falcons for a very long time, maybe 5 million years ago (Ma). They might have come from an ancient group of falcons that spread from Europe to North America. This group also included the ancestors of birds like the American kestrel and the aplomado falcon.

A fossil falcon found in Kansas, USA, supports this idea. This fossil is about 4.3 to 4.8 million years old. It was a bit smaller than a modern merlin but very similar. This suggests that merlins might have first appeared in North America. Then, they spread to Eurasia. The ice ages later separated the groups in Eurasia and North America.

Different Kinds of Merlins

Because merlins have been on both sides of the Atlantic for so long, the groups in Eurasia and North America are quite different. Some people even think they could be separate species.

Merlins have different colors depending on where they live. For example, males of the suckleyi subspecies, found in the Pacific temperate rain forest, are almost black on top. The pallidus subspecies, which is the lightest, has very little dark color. Its upper parts are grey, and its belly is reddish.

Here are some of the main groups of merlins:

- American Merlins

- Falco columbarius columbarius (taiga merlin): Lives in Canada and the northern USA. It migrates south for winter.

- Falco columbarius richardsonii (prairie merlin): Lives in the Great Plains of North America. It usually stays in the same area.

- Falco columbarius suckleyi (black merlin): Lives along the Pacific coast from Alaska to Washington state. It usually stays in the same area.

- Eurasian Merlins

- Falco columbarius/aesalon aesalon (Eurasian merlin): Lives in northern Eurasia, from the British Isles to central Siberia. Most migrate to Europe and the Mediterranean for winter.

- Falco columbarius/aesalon subaesalon (Icelandic merlin): Lives in Iceland and the Faroe Islands. It usually stays in the same area.

- Falco columbarius/aesalon pallidus (pallid merlin): Lives in the Asian steppes. It migrates to southern Central Asia and northern South Asia for winter.

What Does a Merlin Look Like?

Merlins are about 24 to 33 centimeters (9.4 to 13 inches) long. Their wingspan is about 50 to 73 centimeters (20 to 29 inches). They are strong and well-built for their size. Male merlins weigh about 165 grams (5.8 ounces). Females are larger, weighing about 230 grams (8.1 ounces). This difference in size between males and females is common in raptors. It helps them hunt different kinds of prey. This means they need less space to find food for both of them.

Male merlins have a blue-grey back. This color can range from almost black to silver-grey depending on the subspecies. Their undersides are buff or orange with black or reddish-brown streaks. Female and young merlins are brownish-grey to dark brown on top. Their undersides are whitish-buff with brown spots. Merlins do not have very strong face patterns like some other falcons. Young merlins are covered in pale buff down feathers.

Their wing feathers are blackish. The tail usually has three to four wide, blackish bands. The tip of the tail is black with a thin white band. This tail pattern is quite unique. Their eyes and beak are dark, and the beak has a yellow area called a cere. Their feet are also yellow with black claws.

Light-colored male merlins in America might look like the American kestrel. However, merlin males have a grey back and tail, while kestrels have reddish-brown. In Europe, light males can be told apart from kestrels by their mostly brown wings.

Where Merlins Live and How They Hunt

Merlins live in open areas. These include willow or birch bushes, shrubland, and even light taiga forests. They also live in parks, grasslands like steppes and prairies, or moorlands. They are not very picky about their habitat. They can be found from sea level up to the treeline. Generally, they like places with a mix of low and medium-height plants and some trees. They avoid thick forests and very dry, treeless areas. When they are migrating, they will use almost any habitat.

Most merlin groups migrate to warmer places for winter. Birds from northern Europe fly to southern Europe and North Africa. North American merlins fly to the southern United States or northern South America. In places with milder weather, like Great Britain or western Iceland, they might just move from higher ground to coasts and lowlands for winter.

Merlins hunt using their speed and quickness. They often fly fast and low, usually less than 1 meter (3 feet) above the ground. They use trees and bushes to surprise their prey. They catch most of their prey in the air. They will chase birds that are startled. Merlins are among the best aerial hunters of small to medium-sized birds. Breeding pairs often hunt together. One bird will scare the prey towards its mate.

Merlins are quite brave. They will attack almost anything that moves a lot. They have even been seen trying to "catch" automobiles and trains. They are very good hunters. Usually, they catch one out of every 20 targets. In good conditions, almost every other attack is successful. Sometimes, merlins will hide food to eat later.

Merlin's Diet and Predators

During the breeding season, most of their food is small birds. These birds usually weigh between 10 and 40 grams (0.35 to 1.4 ounces). Merlins will eat almost any small bird that is common in their area. This includes larks, pipits, finches, house sparrows, and buntings. Young, inexperienced birds are always a favorite. Smaller birds usually try to avoid a hunting merlin. In the Cayman Islands, some small birds were so scared by merlins that they died from stress without being touched.

Merlins also eat larger birds like sandpipers, ducks, and even rock doves (which can be as heavy as the merlin itself). Other animals like insects (dragonflies, moths), small mammals (bats, voles), reptiles (lizards, snakes), and amphibians are also part of their diet. These foods are more important outside the breeding season.

Corvids (like crows and magpies) are the main threat to merlin eggs and young birds. Adult merlins can be hunted by larger raptors. These include peregrine falcons, eagle-owls, and larger hawks. However, most meat-eating birds avoid merlins because merlins are very aggressive and quick. Merlins are known for chasing away larger raptors from their territory. This behavior can even help people identify them.

Merlin Reproduction and Life Cycle

Merlins usually breed in May or June. They stay with the same partner for at least one breeding season. Merlins do not build their own nests. Most of them use old nests made by corvids (like crows or magpies) or hawks. These nests are usually in conifer or mixed tree areas. In moorlands, especially in the UK, the female will make a small dip in thick heather to use as a nest. Some merlins also nest in cracks on cliffs or on the ground. A few might even use buildings.

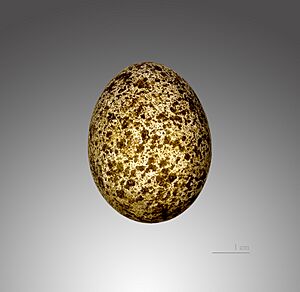

They lay three to six eggs, but usually four or five. The eggs are rusty brown and are about 40 by 31.5 millimeters (1.6 by 1.2 inches) in size. The eggs hatch after 28 to 32 days. The female does most of the incubation, about 90% of the time. The male hunts to feed the family. Young merlins weigh about 13 grams (0.46 ounces) when they hatch. They leave the nest after about 30 more days. They stay with their parents for up to four more weeks.

More than half of the eggs usually hatch, and at least two-thirds of the young birds survive to leave the nest. Sometimes, young merlins (especially males) will help an adult pair with their nest. Merlins become ready to breed at one year old. The oldest wild merlin known was 13 years old.

Merlins and People

John James Audubon drew the merlin in his famous book Birds of America in the 1800s. He called it "Le Petit Caporal."

Merlins in Falconry

In medieval Europe, merlins were popular for falconry. They were known as "the falcon for a lady." They were good at chasing skylarks by circling quickly upwards. Merlins are only a little bigger than American kestrels. However, they weigh about one-third to one-half more. This extra weight is mostly muscle, which gives them more speed and strength.

Today, merlins are still used in falconry. They can hunt sparrows and starlings all year round, even in cities. This means falconers do not need large areas of land or hunting dogs. Merlins can also hunt small game birds like doves and quail during hunting season. A large, strong female merlin might even catch pigeons or small ducks. They offer an exciting way to hunt, often at a closer range than larger falcons. This makes it easier for the falconer to watch and enjoy the flight. Merlins will chase prey that tries to fly higher, and they can dive at high speeds like larger falcons.

An expert falconer, Matthew Mullenix, said that merlins offer "raw power." He noted that they can handle wind well and fly at amazing speeds. He also said that one merlin can control an entire flock of scared birds, making them move like small fish trying to escape a bigger fish. He believes merlins show "total mastery of their element." For hunting, he suggests merlins are best for snipe, doves, quail, and open-country sparrows. For starlings in open areas, merlins are also best.

Protecting Merlins

Overall, the merlin is not a rare bird. Because it lives in so many places, the IUCN considers it a species of least concern. Its numbers are regularly counted in most countries where it lives. There are thousands of merlins in many major countries. For example, in 1993, there were about 30,000 pairs of aesalon merlins in European Russia. Merlins are protected like other birds of prey. In some countries, people can catch merlins, for example, for falconry. However, trading them internationally requires a special permit.

The biggest long-term threat to merlins is the loss of their habitat. This is especially true in their breeding areas. Merlins that nest on the ground in moorlands prefer tall heather. So, if large areas are burned instead of creating a mix of old and new plants, it can hurt them. Still, merlins can adapt to different conditions. They can even live in settled areas if there is a good mix of low and high plants, enough prey, and places to nest.

In North America, merlins might have lived in more places in the past, or their range might have moved north. For example, F. c. columbarius used to breed in Ohio before the 1900s, but now it is rare there during breeding season. It is mostly seen in Ohio during migration or sometimes in winter. Global warming might be a reason for this shift, as merlins are mostly a subarctic species.

One common cause of accidental death for merlins is hitting man-made objects, especially when they are hunting. This can cause almost half of all early deaths for merlins. In the 1960s and 1970s, certain organochlorine pesticides caused merlin numbers to drop. These chemicals made eggshells thin, causing eggs to break. They also weakened the birds' immune systems. Since then, these chemicals have been restricted, and merlin numbers have recovered. Overall, merlin populations seem stable worldwide. Even if their numbers drop in some places for a while, they usually increase again.

See also

- Perlin, a hybrid of a merlin and a peregrine falcon.

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |