River Trent facts for kids

Quick facts for kids River Trent |

|

|---|---|

Trent Bridge, with Nottingham in the background

|

|

Drainage basin of the River Trent (Interactive map)

|

|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Country within the UK | England |

| Counties | Staffordshire, Derbyshire, Leicestershire, Nottinghamshire, Lincolnshire, Yorkshire |

| Cities | Stoke-on-Trent, Nottingham |

| Towns | Stone, Rugeley, Burton upon Trent, Newark-on-Trent, Gainsborough |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Main source | Biddulph Moor, Staffordshire, England 275 m (902 ft) 53°06′58″N 02°08′25″W / 53.11611°N 2.14028°W |

| River mouth | Trent Falls, Humber Estuary, Lincolnshire, England 0 m (0 ft) 53°42′N 0°42′W / 53.700°N 0.700°W |

| Length | 298 km (185 mi) |

| Discharge (location 2) |

|

| Basin features | |

| Progression | River Trent → Humber → North Sea |

| Basin size | 10,435 km2 (4,029 sq mi) |

| Tributaries | |

The Trent is the third longest river in the United Kingdom. It starts in Staffordshire, near Biddulph Moor. The river flows through the North Midlands and empties into the Humber Estuary. The Trent is famous for its big floods after storms or when snow melts. These floods have often changed the river's path in the past.

The river flows through cities like Stoke-on-Trent, Stone, Staffordshire, Rugeley, Burton-upon-Trent, and Nottingham. It then joins the River Ouse, Yorkshire at Trent Falls. Together, they form the Humber Estuary, which flows into the North Sea. The wide Humber estuary is often seen as the border between the Midlands and northern England.

Contents

- What's in a Name?

- The River's Journey

- River Basin and Landscape

- River Rocks and Soil

- How Water Flows in the Trent

- Flooding History

- River Travel History

- Trent Aegir

- The North/South Divide

- Pollution and Clean-up

- Wildlife and Nature

- Fishing on the Trent

- Places Along the Trent

- Crossing the Trent

- Power Stations

- Fun on the Trent

- Rivers Joining the Trent

- Images for kids

- See also

What's in a Name?

The name "Trent" might come from an old Romano-British word. It could mean "strongly flooding" or "over the way." This might suggest a river that often floods. Another idea is that it was a river that could be crossed easily by fords (shallow places to walk across). This could explain why some places along the Trent have "rid" or "ford" in their names.

Some people also think the name means "the trespasser." This refers to the water flooding over the land. A very old, but likely incorrect, idea from 1653 was that it was named after 30 types of fish or 30 smaller rivers joining it.

The River's Journey

The Trent begins in the Staffordshire Moorlands, near Biddulph Moor. It starts from several small sources, including the Trent Head Well. Other small streams join it, forming the Head of Trent. This flows south to Knypersley Reservoir, the only reservoir on its path.

After the reservoir, it flows through Stoke-on-Trent. Here, it joins with other brooks like the Lyme and Fowlea. These brooks drain the towns of the Staffordshire Potteries, making the Trent bigger. South of Stoke, it passes through the beautiful Trentham Gardens.

The river continues south through the town of Stone. After the village of Salt, it reaches Great Haywood. Here, the 16th-century Essex Bridge crosses it near Shugborough Hall. The River Sow also joins the Trent here from Stafford.

The Trent then flows southeast past Rugeley and meets the Blithe at Kings Bromley. After the Swarbourn joins, it passes Alrewas and Wychnor. Here, the A38 road crosses it, following an old Roman road. The river then turns northeast. It is joined by its largest tributary, the River Tame. Right after, the River Mease also joins, making the Trent much wider. It now flows through a large flat area called a floodplain.

The river continues northeast past Walton-on-Trent to Burton-upon-Trent. In Burton, several bridges cross the river, including the beautiful 19th-century Ferry Bridge. This bridge connects Stapenhill to the town. Northeast of Burton, the River Dove joins at Newton Solney. The Trent then enters Derbyshire. It flows between Willington and Repton, turning east to reach Swarkestone Bridge.

Soon after, the river becomes the border between Derbyshire and Leicestershire. It passes King's Mill, Castle Donington, Weston-on-Trent, and Aston-on-Trent.

At Shardlow, where the Trent and Mersey Canal begins, the river meets the Derwent at Derwent Mouth. After this, the river turns northeast and is joined by the River Soar. It then reaches the edge of Nottingham. Here, the River Erewash joins near the Attenborough nature reserve, and the Trent enters Nottinghamshire.

As it enters Nottingham, it passes through areas like Beeston and Clifton. The Leen river joins it near Wilford. At West Bridgford, it flows under Trent Bridge near the famous cricket ground. It also passes The City Ground, home of Nottingham Forest F.C., before reaching Holme Sluices.

Downstream of Nottingham, it passes Radcliffe-on-Trent and Burton Joyce. It then reaches Gunthorpe with its bridge, lock, and weir. The river flows northeast below the Toot and Trent Hills. It then reaches Hazelford Ferry, Fiskerton, and Farndon.

North of Farndon, near the Staythorpe Power Station, the river splits. One part goes past Averham and Kelham. The other part, which boats can use, is joined by the Devon river. It then flows through Newark-on-Trent and under its castle walls. The two parts join back together at Crankley Point. Here, the river turns north, passing North Muskham and Holme. It then reaches Cromwell Weir, where the Trent becomes tidal (meaning its water level changes with the ocean tides).

The tidal river winds across a wide floodplain. Along its edges are villages like Carlton and Sutton on Trent. After passing the site of High Marnham power station, it becomes the border between Nottinghamshire and Lincolnshire. It reaches the only toll bridge on its path at Dunham on Trent.

Downstream of Dunham, the river passes Church Laneham and reaches Torksey. Here, it meets the Foss Dyke canal, which connects the Trent to Lincoln and the River Witham. Further north at Littleborough was a Roman town called Segelocum, where a Roman road once crossed the river.

It then reaches Gainsborough with its own Trent Bridge. The riverfront in Gainsborough has old warehouses. These were used when the town was a busy port. Many have been fixed up for new uses today. Downstream of Gainsborough, villages are often named in pairs, like West Stockwith and East Stockwith. This is because they used to be connected by a river ferry.

At West Stockwith, the Chesterfield Canal and the River Idle join the Trent. Soon after, the Trent fully enters Lincolnshire, passing west of Scunthorpe. The last bridge over the river is at Keadby. Here, the Stainforth and Keadby Canal and the River Torne join it.

Downstream of Keadby, the river gets wider. It passes Amcotts and Flixborough to reach Burton upon Stather and finally Trent Falls. At this point, between Alkborough and Faxfleet, the river meets the River Ouse. They form the Humber, which flows into the North Sea.

How the River Changed Course

The Trent is unusual for an English river because its path has changed a lot over time. It's been compared to the Mississippi in this way. Especially in its middle parts, there are many old bends and places where the river cut off a loop. An old map shows an abandoned channel at Repton called 'Old Trent Water'. Records show this was once the main path for boats. The river moved to a more northern path in the 1700s.

At Hemington, archaeologists found parts of a medieval bridge. This bridge crossed another old river channel. Scientists have used aerial photos and old maps to find many of these old river paths. A good example is a cut-off bend at Sawley.

The river's habit of changing course is even mentioned in Shakespeare's play Henry IV, Part 1. In the play, a character named Henry Hotspur complains about the river:

Methinks my moiety, north from Burton here,

In quantity equals not one of yours:

See how this river comes me cranking in,

And cuts me from the best of all my land

A huge half-moon, a monstrous cantle out.

I'll have the current in this place damm'd up;

And here the smug and silver Trent shall run

In a new channel, fair and evenly;

It shall not wind with such a deep indent,

To rob me of so rich a bottom here.—William Shakespeare, Henry IV, Part 1, act 3, scene I

Hotspur's speech about the river's bends might refer to the meanders near West Burton. But in the play, he wants to divide England. So, he might have planned to move the river east towards the Wash. This would give him a much bigger share of the kingdom. The idea for this scene might have come from a real disagreement. This was about a mill weir near Shelford Manor in 1593.

The Trent in Ancient Times

Long, long ago (about 1.7 million years ago), the River Trent started in the Welsh hills. It flowed east from Nottingham through the Vale of Belvoir. It then cut a path through the limestone hills at Ancaster to the North Sea.

Later, about 130,000 years ago, a huge block of ice in the Vale of Belvoir made the river change direction. It flowed north along an old river path, through the Lincoln gap. This is now the path of the River Witham.

During another ice age (about 70,000 BC), the ice held back huge amounts of water. This formed a giant lake called Glacial Lake Humber in the lower Trent area. When the ice melted, the Trent started flowing into the Humber, just as it does today.

River Basin and Landscape

The Trent river basin covers a large part of the Midlands. It includes most of Staffordshire, Derbyshire, Leicestershire, Nottinghamshire, and the West Midlands. It also touches parts of Lincolnshire, South Yorkshire, Warwickshire, and Rutland. This area is located between other river basins like the Severn to the south and west.

The landscape of the Trent basin changes a lot. It goes from high moorland areas in the Dark Peak, where the highest point is Kinder Scout at 634 metres (2,080 ft). Then it goes down to flat, farmed fenland areas near the lower tidal parts. In these low areas, the ground can be at sea level. Walls and defenses protect these areas from tidal floods.

There are also open limestone areas in the White Peak (near the Dove river). And there are large woodland areas like Sherwood Forest and the National Forest.

| Land use |

|

Most of the land (about three-quarters) in the Trent basin is used for farming. This includes sheep grazing in the high areas. In the middle parts, there are mixed farms and dairy farms. In the lowlands, farmers grow cereals and root vegetables like potatoes and sugar beet.

Managing water levels is important in these low areas. Local waterways are often kept clear by special boards. Pumps are used to lift water into raised rivers, which then flow into the Trent.

There are many large cities and towns in the Trent basin. These include Stoke-on-Trent, Birmingham, Leicester, Derby, and Nottingham. Most of the 6 million people living in the basin live in these urban areas.

Many of these cities are in the upper parts of the Trent or its smaller rivers. For example, Birmingham is at the top of the Tame river. This means there have been ongoing problems with urban runoff, pollution, and waste from sewage treatment and industry. In the past, this made the water quality of the Trent and its rivers very bad. To get clean water, Birmingham built a large system of reservoirs and aqueducts to bring water from the Elan Valley.

River Rocks and Soil

The upper parts of the Trent flow over rocks like Millstone Grit and Carboniferous Coal Measures. These include layers of sandstone, marl, and coal. The river crosses Triassic Sherwood sandstone at Sandon and again near Cannock Chase.

Further downstream, the main rock is Mercia Mudstones. The river follows the curve of these mudstones all the way to the Humber. These mudstones are not usually seen at the riverbed. This is because there are layers of gravel and then alluvium (river silt) on top. But in some places, the mudstones form cliffs along the river. This is most noticeable at Gunthorpe and Stoke Lock near Radcliffe on Trent. The village of Radcliffe is named after the red color of these rocks.

The low hills overlooking the Trent between Scunthorpe and Alkborough are also made of mudstones. These are from the younger Rhaetic Penarth Group.

The wider Trent basin has many different types of rock. These range from very old Precambrian rocks in Charnwood Forest to Jurassic limestone that forms the Lincolnshire Edge. The most important rocks for the river are the large sandstone and limestone layers underground. These are called aquifers. They are found under many of the smaller rivers that flow into the Trent. These aquifers provide water to the rivers and are also an important source of public drinking water.

| Gravel Terraces of the River Trent | ||

|---|---|---|

| Name | Age thousand yrs BP |

Stage |

| Eagle Moor | > 400 | Anglian |

| Etwall / Whisby Farm |

297 | Early Wolstonian |

| Egginton / Balderton |

195 | Late Wolstonian |

| Beeston / Scarle |

80 | Devensian |

| Holme Pierrepont | 26 | Devensian |

| Hemington | 10 | Flandrian |

Sand, gravel, and alluvium (river mud) cover the mudstone bedrock along almost the entire river. These are important in the middle and lower parts of the river. The alluvial silt creates fertile soils, which are used for intensive farming in the Trent valley.

Under the alluvium are large amounts of sand and gravel. These also form gravel terraces much higher than the current river level. There are at least six different gravel terrace systems along the river. They were formed when a much larger Trent flowed through the valley. These terraces were created by periods of deposition (stuff settling) and then the river cutting down. This happened because of meltwater and material from ice sheets at the end of ice ages.

These terraces contain evidence of huge animals that once lived along the river. Bones and teeth of animals like woolly mammoths, bison, and wolves have been found. A famous find near Derby was the Allenton hippopotamus, from a warmer period between ice ages.

The lower parts of these terraces have been widely dug up for sand and gravel. This is still an important industry in the Trent Valley, producing about three million tonnes of materials each year. Once the gravel is dug out, the pits often fill with water. These flooded pits are then used for many things, like water sports or as nature reserves.

At the end of the last ice age, a lake called Lake Humber formed in the lowest parts of the river. This laid down thick layers of clay and silt, creating the flat land of the Humberhead Levels. In some areas, layers of peat (decayed plant matter) built up on top of these lake deposits. This created wetlands like the Thorne and Hatfield Moors.

How Water Flows in the Trent

The landscape, geology, and land use of the Trent basin all affect how water flows in the river. These different factors also mean that the main rivers that flow into the Trent have different ways of collecting and releasing water. The largest of these is the River Tame. It provides almost a quarter of the total water flow for the Trent. Other important rivers are the Derwent (18%), Soar (17%), Dove (13%), and Sow (8%). Four of these main rivers, including the Dove and Derwent from the Peak District, all join the Trent in its middle parts. This makes the Trent a fairly strong river system for the UK.

Rainfall in the Trent Basin

Rainfall in the Trent basin generally follows the land's height. The highest rainfall (1,450 mm (57 in) and more) happens over the high moorland areas where the Derwent river starts. The lowest rainfall (580 mm (23 in)) is in the lowlands to the north and east. The Tame river basin doesn't get as much rain as you might expect. This is because the Welsh mountains to the west block some of the rain. The average for the Tame basin is 691 mm (27.2 in).

The average rainfall for the whole Trent basin is 720 mm (28 in). This is much lower than the average for the United Kingdom (1,101 mm (43.3 in)) and England (828 mm (32.6 in)).

Like other large lowland rivers in Britain, the Trent can flood after long periods of rain. This often happens in autumn and winter when water doesn't evaporate much. This can make the land very wet, so any extra rain quickly flows into the river. This happened in February 1977, causing widespread flooding in the lower Trent. In 2000, heavy autumn rain also led to floods in November.

Another risk, though less common, is when a lot of snow melts quickly. This can happen if temperatures suddenly rise or if it rains heavily on top of snow. Many of the biggest floods in history were caused by melting snow. The last big one was in March 1947, after a very cold winter. This caused severe flooding all along the Trent valley.

On the other hand, long periods of low rainfall can also cause problems. The lowest flows for the river were recorded during the drought of 1976. Flows at Nottingham were extremely low, something that happens less than once every hundred years.

How Much Water Flows?

| Discharge of the River Trent at various locations | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gauging Station |

County | Discharge (average) |

Discharge (maximum) |

Catchment Area |

||||||

| m3/s | cfs | m3/s | cfs | km2 | mi2 | |||||

| Stoke on Trent | 0.6 | 21 | 55 | 1,900 | 53 | 20 | ||||

| Great Haywood | 4.4 | 160 | 98 | 3,500 | 325 | 125 | ||||

| Yoxall | 12.8 | 450 | 206 | 7,300 | 1,229 | 475 | ||||

| Drakelow | 36.1 | 1,270 | 385 | 13,600 | 3,072 | 1,186 | ||||

| Shardlow | 51.6 | 1,820 | 480 | 17,000 | 4,400 | 1,700 | ||||

| Colwick | 83.8 | 2,960 | 1,018 | 36,000 | 7,486 | 2,890 | ||||

| North Muskham | 88.4 | 3,120 | 1,000 | 35,000 | 8,231 | 3,178 | ||||

The river's flow is measured at several points. At Stoke-on-Trent, the average flow is only 0.6 m3/s (21 cu ft/s). This increases to 4.4 m3/s (160 cu ft/s) at Great Haywood. This is because water from the Potteries towns joins the river. At Yoxall, the flow reaches 12.8 m3/s (450 cu ft/s) due to rivers like the Sow and Blithe.

At Drakelow, the flow nearly triples to 36.1 m3/s (1,270 cu ft/s). This is because the Tame, the largest tributary, joins here. At Colwick near Nottingham, the average flow rises to 83.8 m3/s (2,960 cu ft/s). This is due to the Dove, Derwent, and Soar rivers joining. The last measurement point is North Muskham. Here, the average flow is 88.4 m3/s (3,120 cu ft/s). This small increase is from the Devon and other smaller rivers.

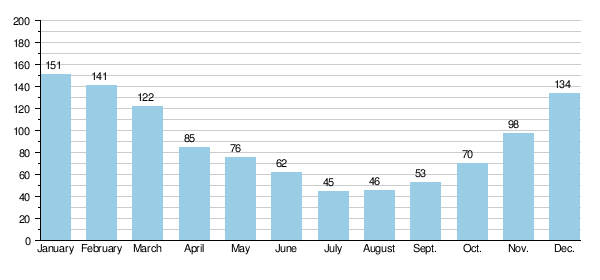

The Trent's flow changes a lot throughout the year. At Colwick, the average monthly flow is 45 m3/s (1,600 cu ft/s) in July (summer). It increases to 151 m3/s (5,300 cu ft/s) in January (winter).

When the river flow is low, the Trent and its smaller rivers are greatly affected by water from sewage treatment plants. For example, in summer, up to 90% of the Tame's flow can be from treated wastewater. For the Trent, this is less, but still important. Also, water from underground rock layers (aquifers) adds to the river's flow.

Average monthly flows of Trent in cubic metres per second measured at Colwick (Nottingham).

River Sediment

In its lower tidal parts, the Trent carries a lot of fine silt. This silt, also called 'warp', was used to improve farm soil. River water was allowed to flood into fields through special drains. The silt would then settle on the land. Up to 0.3 metres (1 ft) of silt could be deposited in one season. In some places, 1.5 metres (5 ft) of silt built up over time. Some smaller rivers that flow into the Trent are still called warping drains, like Morton warping drain.

Warp was also sold. It was collected from the river banks at low tide. Then it was taken along the Chesterfield Canal to Walkeringham. There, it was dried and refined to be sold as a silver polish.

Flooding History

| Largest floods on the River Trent at Nottingham | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Date | Level at Trent Bridge | Peak Flow | |||

| m | ft | m3/s | cfs | |||

| 1 | February 1795 | 24.55 | 80.5 | 1,416 | 50,000 | |

| 2 | October 1875 | 24.38 | 80.0 | 1,274 | 45,000 | |

| 3 | March 1947 | 24.30 | 79.7 | 1,107 | 39,100 | |

| 4 | November 1852 | 24.26 | 79.6 | 1,082 | 38,200 | |

| 5 | November 2000 | 23.80 | 78.1 | 1,019 | 36,000 | |

| Normal / Avg flow | 20.7 | 68 | 84 | 3,000 | ||

The Trent is well known for causing big floods. There are records of floods going back about 900 years. In Nottingham, the heights of major floods since 1852 are carved into a bridge. These marks were moved from an older bridge. Flood levels have also been recorded at Girton and on a church wall at Collingham.

One of the earliest recorded floods was in 1141. Like many other big floods, it happened when snow melted after heavy rain. This flood also broke a floodbank at Spalford. This bank only broke when flows were greater than 1,000 m3/s (35,000 cu ft/s). The bank also broke in 1403 and 1795.

Old bridges were easily damaged by floods. In 1309, many bridges were washed away or damaged by severe winter floods. This included Hethbeth Bridge. In 1683, the same bridge was partly destroyed by a flood. The bridge at Newark was also lost. Old records often talk about bridge repairs after floods. The money for these repairs was raised by borrowing and charging a local toll.

The biggest known flood was in February 1795. This followed eight weeks of harsh winter weather. Rivers froze, stopping mills from grinding grain. Then, a quick thaw happened. Because the flood was so big and carried ice, almost every bridge along the Trent was badly damaged or washed away. Bridges at Wolseley, Wychnor, and Swarkestone were all destroyed.

The main flood of the 1800s, and the second largest ever recorded, was in October 1875.

Flooding on the Trent can also be caused by storm surges from the sea. These are separate from river flows. A series of storm surges in October and November 1954 caused the worst tidal flooding in the lower river. These floods showed that a tidal protection plan was needed. This plan would handle the water levels from 1947 and the tidal levels from 1954. So, the floodbanks and defenses along the lower river were improved by 1965. In December 2013, the biggest storm surge since the 1950s happened. A high tide combined with strong winds and low pressure. This caused high tidal river levels in the lower parts of the river. The surge went over the flood defenses near Keadby and Burringham, flooding 50 homes.

The fifth largest flood recorded at Nottingham happened in November 2000. This caused widespread flooding of low-lying land along the Trent valley. Many roads and railways were flooded. The flood defenses around Nottingham and Burton, built after the 1947 flood, stopped major city flooding. But problems happened in unprotected areas like Willington and Gunthorpe. In Girton, 19 houses were flooded.

After this flood, the defenses in Nottingham (protecting 16,000 homes) and Burton (protecting 7,000 homes) were checked. They were then improved between 2006 and 2012.

River Travel History

Nottingham was likely the main point for boats until the 1600s. This was partly because it was hard to navigate past Trent Bridge. Later, river travel was extended to Wilden Ferry. This was thanks to the Fosbrooke family of Shardlow.

| River Trent Navigation Act 1698 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

|

|

| Long title | An Act for makeing and keeping the River Trent in the River Trent in the Counties of Leicester Derby and Stafford navigable. |

| Citation | 10 Will. 3. c. 26 (Ruffhead: 10 & 11 Will. 3. c. 20) |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 4 May 1699 |

In 1699, William Paget, a lord who owned coal mines, got a special law passed. This law allowed him to extend river travel up to Fleetstones Bridge, Burton. He paid for the work himself, building locks at King's Mill and Burton Mills. He also built several cuts (new channels) and basins. The law gave him full control over building wharves (docks) and warehouses above Nottingham Bridge.

Lord Paget rented out the river travel rights and the wharf at Burton to George Hayne. The wharf at Wilden was rented by Leonard Fosbrooke. These two men worked together. They refused to let any goods be landed unless they were carried in their own boats. This created a monopoly, meaning they controlled all the business.

In 1748, merchants from Nottingham tried to break this monopoly. They tried to unload goods directly onto the banks. But Fosbrooke used his ferry rope to block the river. He then made a bridge by tying boats across the channel and hired men to defend them. Hayne later sank a barge in King's Lock. For the next eight years, goods had to be moved around this blockage. Even with a court order against them, they continued. Hayne's rental agreement ended in 1762. Lord Paget's son then gave the new rental to the Burton Boat Company.

The Trent and Mersey Canal was approved in 1766. It was finished by 1777, connecting Shardlow to Preston Brook. The canal ran next to the upper river to Burton upon Trent. New docks at Horninglow served the town. The Burton Boat Company couldn't fix the river's bad reputation caused by the previous renters. In 1805, they agreed with a canal company to close the river above Wilden Ferry. While the river might still legally be open for boats above Shardlow, this agreement likely ended its use for commercial travel.

Improving the Lower River

The first improvements to the lower river were at Newark. Here, the river splits into two. The townspeople wanted to use the branch closest to them more. So, a law was passed in 1772 to allow this work. The Newark Navigation Commissioners were created. They could borrow money to build two locks and charge tolls for boats using them. The work was finished by October 1773. The separate tolls lasted until 1783. Then, a single toll of one shilling (5p) was charged, no matter which channel boats used.

People using the Trent and Mersey Canal and other canals wanted big improvements to the river down to Gainsborough. This included new cuts, locks, dredging (making the river deeper), and a path for horses to pull boats. Engineers thought it would cost £20,000. But landowners and merchants on the river were against it. They worried that about 500 men who pulled boats would lose their jobs.

They couldn't agree, so William Jessop was asked to look again. He suggested that dredging and making the channel narrower could make it deep enough. He also said cuts would be needed at Wilford, Nottingham bridge, and Holme. This plan became the basis for a law passed in 1783. This law also allowed a horse towing path to be built. The work was finished by September 1787. The company paid good returns on the money invested. Jessop surveyed for a side cut and lock at Sawley in 1789, which was built by 1793.

In the early 1790s, there were calls to bypass the river at Nottingham. The passage past Trent Bridge was dangerous. There was also a threat of a canal being built next to the river. This was proposed by other canal companies. To keep control of the whole river, the Trent Navigation Company supported including the Beeston Cut in the bill for the Nottingham Canal. This stopped the other company from getting permission. Then they had the proposal removed from the Nottingham Canal bill.

The idea of a parallel canal was stopped in May 1793. The company agreed to withdraw the canal bill. Instead, they proposed a full survey of the river, which would lead to their own law. William Jessop did the survey, helped by Robert Whitworth. They published their report on July 8, 1793. Their main ideas included a cut and lock at Cranfleet, where the River Soar joins the Trent. Also, cuts, locks, and weirs at Beeston to connect with the Nottingham Canal. And a cut and lock at Holme Pierrepont. A law was passed in 1794. The existing owners invested all the money needed, £13,000.

The goal of these improvements was to increase the minimum depth from 2 feet (0.6 m) to 3 feet (0.9 m). By early 1796, the Beeston cut was working. The Cranfleet cut followed in 1797, and the Holme cut in 1800. All the work was finished by September 1, 1801. The cost was much higher than planned, and extra money had to be borrowed. But the company continued to pay a good return on the shares. In 1823 and 1831, the Newark Navigation Commissioners suggested more improvements. They wanted to allow larger boats. But the Trent Navigation Company was making good money and didn't see the need.

Challenges and Modernization

The arrival of railways changed things a lot for the company. They lowered tolls to keep traffic and raised wages to keep workers. They also tried to join with a railway company. But their offers were rejected. Tolls dropped significantly. Many connecting waterways were bought by railway companies and fell into disrepair. To improve things, the company thought about using steam tugs. Instead, they bought a steam dredger and some tugs.

The cost of improvements was too high for the old company. So, laws were passed in 1884 and 1887 to reorganize the company and raise more money. But they couldn't raise much. A third law in 1892 brought back the name Trent Navigation Company. This time, some improvements were made.

With traffic still between 350,000 and 400,000 tonnes per year, Frank Rayner became the engineer in 1896. He convinced the company that major work was needed for the river to survive. Sir Edward Leader Williams, an engineer for the Manchester Ship Canal, was asked to survey the river. A plan to build six locks between Cromwell and Holme and to dredge this section was approved in 1906. This would make it 60 feet (18 m) wide and 5 feet (1.5 m) deep.

Raising money was hard, but the chairman and vice-chairman invested some. Construction of Cromwell Lock began in 1908. The Newark Navigation Commissioners paid for improvements to Newark Town lock at the same time. Dredging the channel was mostly paid for by selling the 400,000 tonnes of gravel removed from the riverbed. Cromwell lock was 188 by 30 feet (57.3 by 9.1 m) and could hold a tug and three barges. It opened on May 22, 1911. Transporting petroleum (oil) brought a welcome increase in trade. But little more work was done before World War I.

After World War I, running costs increased. The company couldn't raise tolls, so they suggested the Ministry of Transport take over. This happened on September 24, 1920. Tolls were increased, and a committee suggested more river improvements. Nottingham Corporation invested about £450,000 to build the locks approved in the 1906 law. Work started with Holme lock in 1921 and finished with Hazelford lock, opened in 1926. A loan and a grant helped the company rebuild Newark Nether lock, which opened in 1926.

In the early 1930s, the company thought about making the river bigger above Nottingham. They also talked with the London and North Eastern Railway about the Nottingham Canal. Plans for new, larger locks at Beeston and Wilford were stopped. This was because the Trent Catchment Board was against them. The company also thought about reopening the river to Burton. This would have meant rebuilding Kings Mills lock and building four new ones.

Extra gates were added to Cromwell lock in 1935, making it like a second lock. The section from Lenton to Trent Lock was rented in 1936 and bought in 1946.

Frank Rayner, who had worked for the company since 1887, died in 1945. Sir Ernest Jardine, who had helped fund Cromwell lock, died in 1947. The company ended in 1948 when the waterways were taken over by the government. The last thing the directors did was pay a 7.5% dividend on shares in 1950.

The Transport Commission took over the waterway. They made Newark Town lock bigger in 1952. The flood lock at Holme was removed to reduce flood risk in Nottingham. More improvements happened between 1957 and 1960. The two locks at Cromwell became one, big enough for eight Trent barges. Dredging equipment was updated, and several locks were made automatic.

Traffic increased from 620,000 tonnes in 1951 to over 1 million tonnes in 1964. But all of this was below Nottingham. Commercial use of the river above Nottingham stopped in the 1950s. It was replaced by pleasure boating.

Even though commercial use has gone down, the lower river between Cromwell and Nottingham can still take large barges. These can be up to 150 feet (46 m) long and carry about 300 tonnes. Barges still transport gravel from pits at Girton and Besthorpe to Goole and Hull.

The river is legally open for boats for about 117 miles (188 km) below Burton upon Trent. However, for practical reasons, boats usually use the Trent and Mersey Canal above Shardlow. The canal connects the Trent to the Potteries and then to Runcorn and the Bridgewater Canal.

Downstream of Shardlow, the non-tidal river can be used by boats as far as Cromwell Lock near Newark. There are also two canal sections near Nottingham: Beeston Cut and Nottingham Canal. Below Cromwell lock, the Trent is tidal. This means its water level changes with the ocean tides. Only experienced boaters with proper equipment should navigate here. Navigation lights, a good anchor, and cable are a must. Associated British Ports, which manages the river from Gainsborough to Trent Falls, says that anyone in charge of a boat must be experienced in tidal waters.

Between Trent Falls and Keadby, coastal vessels (ships that travel along the coast) still deliver goods to wharves (docks). The largest vessels that can fit are 100 m (330 ft) long and weigh 4,500 tonnes.

It's not required to have a special pilot for commercial boats on the Trent. But it's suggested for those without experience in the river. Navigation can be tricky. There have been cases of ships running aground and hitting Keadby Bridge. Recently, a ship called the Celtic Endeavour was stuck near Gunness for ten days.

Trent Aegir

At certain times of the year, the lower tidal parts of the Trent have a moderately large tidal bore. This is a wave that travels upstream. It's known as the Trent Aegir, named after the Norse sea god. The Aegir happens when a high spring tide (a very high tide) meets the river's flow. The funnel shape of the river mouth makes this wave bigger. It can travel upstream as far as Gainsborough, Lincolnshire, and sometimes even further. The Aegir can't go much beyond Gainsborough because the river's shape makes it smaller. Weirs (small dams) north of Newark-on-Trent stop it completely.

The North/South Divide

The Trent historically marked the boundary between Northern England and Southern England. For example, the rules for royal forests were different north and south of the river. Also, the medieval Council of the North (a government body) had power starting at the Trent.

The University of Oxford used to divide its students into a northern group and a southern group. The northern group included English people from north of the Trent and Scots. The southern group included English people from south of the Trent, Irish, and Welsh.

Some signs of this old division still exist. The Trent marks the boundary between the areas of two English Kings of Arms (officials who deal with coats of arms). This division was also described in a long poem from 1622:

And of the British floods, though but the third I be,

Yet Thames and Severne both in this come short of me,

For that I am the mere of England, that divides

The north part from the south, on my so either sides,

that reckoning how these tracts in compasse be extent,

Men bound them on the north, or on the south of Trent

Pollution and Clean-up

It's not clear when pollution first became a problem for the River Trent. But in the late 1880s, it had a lot of salmon. About 3,000 fish were caught each year. Ten years later, this number dropped to only 100. The salmon disappeared because towns grew quickly after the Industrial Revolution. When pipes and sewers were introduced, waste that used to stay in cesspits was carried into the nearest river.

...the polluted state of the Trent is a terror to Trentham.

This was a big problem in Stoke-on-Trent and the growing towns of the Potteries. The Trent and its small rivers like the Fowlea Brook were too small to dilute all the sewage. They quickly became very polluted.

At the end of the Potteries area was Trentham Hall. The pollution here became so bad that the owner, the Duke of Sutherland, complained in 1902. He also got a court order to stop the pollution, which caused a "most foul and offensive stench." The river water was not even safe for cattle to drink.

Even though he provided land for a sewage works nearby, the problems continued. In 1905, the Levenson-Gower family left Trentham completely.

Until World War II, the main source of pollution was still the Potteries. Although there was pollution from the Tame and other rivers, it wasn't as bad. However, in the 1950s, the same problem of waste water became serious in Birmingham and the Black Country. Waste from homes and metal industries in the upper parts of the Tame river affected its entire length.

The Tame's pollution also reached the Trent. One of the worst affected areas was downstream of where the Tame joined the Trent, through Burton. This was made worse because Burton was slow to introduce sewage treatment. Also, there was a lot of wastewater from the breweries in the town. Fishing clubs in Burton used other rivers or lakes because the Trent through the town had no fish. Further downstream, cleaner water from the Dove and Derwent rivers improved conditions. This allowed for recreational fishing in the lower parts of the Trent.

The pollution in the "Trent basin was probably at its worst in the late 1950s." This was due to ongoing industrial growth and a lack of investment in sewage treatment because of two world wars. As a result, the upper and middle parts of the river had no fish at all.

I received this morning a letter from the secretary of a Burton rowing club.

Last Thursday, its senior eight were out rowing when

members of the crew were seized with pains in the chest.

This was caused by fumes rising from the river.

John Jennings, the local Member of Parliament for Burton, spoke about these problems in 1956. He said the river had been declared unsafe for swimming. He also mentioned how its unhealthy state affected a local rowing club.

From the 1960s onwards, there were slow but steady improvements to the old sewage works and sewers in cities. This was expensive and took time. Changes were helped by stricter pollution control laws. These laws required industrial waste to be sent to sewers. Also, the Trent River Authority was formed. It had new duties to manage water quality. Other changes, like replacing town gas with natural gas, stopped polluting coal tar from going into rivers in 1963.

In 1970, Mr. Jennings again raised the issue of pollution through Burton. The River Tame was still a problem, and more improvements were promised. Local authorities were still in charge of sewage treatment. This often meant a messy approach with many small treatment plants. In 1974, these plants were transferred to regional water authorities. The Severn Trent Water Authority took over for the Trent basin. This led to more investment. Older, smaller plants were closed, and sewage treatment was combined at larger, modern plants.

The economic downturn in the 1970s meant that heavy industries shrank. This reduced the amount of pollution from factories. Later improvements included building a series of purification lakes on the Tame in the 1980s. These lakes allowed polluted mud to settle out of the river. This also reduced pollution levels in the lower Tame and middle Trent.

Improvements in water quality were tracked by chemical monitoring from the 1950s. Polluting substances like ammonia decreased. The Biochemical Oxygen Demand (a measure of pollution) also went down. At the same time, dissolved oxygen (a sign of a healthy river) increased.

The monitoring program also took biological samples. One of the first ways to measure the ecological quality of rivers (not just chemical) was developed by the local river board in the 1960s. It used invertebrates (animals without backbones) to show pollution levels. It was called the Trent Biotic index.

By 2004, the Trent was reported to be cleaner than it had been in 70–80 years. Pollution incidents had also greatly reduced since the 1970s. The river can still be affected by pollution events. For example, in October 2009, cyanide accidentally leaked from a factory into the sewer system in Stoke-on-Trent. This affected the treatment works and led to raw sewage and the chemical being released into the river. Thousands of fish died, and it posed a health risk to river users as far south as Burton.

Even though it's cleaner now, there are still problems with pollution from farms and cities. Also, there's pollution from sewage works. But because of the improvements, the Trent's water can now be used for drinking. Lakes near Shardlow act as a backup water source for Nottingham and Derby. Water is also taken from Torksey and Newton-on-Trent for supplies in Lincolnshire.

Wildlife and Nature

Changes along the Trent, like building for boats, farming, and mining, have changed much of the natural riverside land. This has reduced the amount of natural habitat. The river connects the remaining wetland areas and nature reserves. These places provide a safe home for native animals and birds that migrate. This includes wildfowl and wading birds that use the Trent Valley as a migration corridor. Mammals like otters and non-native American mink also use the river as a wildlife path. It's part of the Severn-Trent flyway, a route for migratory birds across Great Britain.

More nature areas were created next to the river in the 1900s. Many old gravel pits were turned into nature reserves. One of the most important is Attenborough Nature Reserve. This is a 226-hectare (560-acre) Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI). Wildfowl like Eurasian wigeon and common teal visit it. Wading birds like Eurasian oystercatcher and great bittern have also been seen there. So have kingfishers, reed warblers, and water rails.

Other managed wetland sites along the river include Beckingham Marshes, Croxall Lakes, Drakelow, and Willington Gravel Pits. At Besthorpe near Newark, little egrets and grey herons have been seen nesting.

The Trent valley also links other SSSI and local nature reserves. These have different habitats for birds, mammals, insects, and fish. A good example is the River Mease. Its entire watercourse is a SSSI and a European special area of conservation.

One unusual nature site is Pasturefields nature reserve near Hixon. This is an inland saltmarsh, which is rare in the UK. It's a leftover from salty marshes created by brine springs. These springs seep from the underground Mercia mudstones. The reserve has salt-tolerant plants usually found on the coast, like sea plantain and milkwort.

Improvements in water quality and fish numbers, along with a ban on certain harmful pesticides, mean that otters have returned to the Trent system. They were gone as recently as the 1980s. A survey in 2003 showed twice as many places where signs of these shy animals were found. They have also been seen at places like Wolseley, Willington, and Attenborough. Seals have been reported near the start of the tidal section at Newark.

Fishing on the Trent

Evidence of fishing along the Trent goes back to the Stone Age. Possible remains of a fish weir (a fence to trap fish) were found in old river channels at Hemington. More clear finds from the medieval period were also found there and near Colwick. These were V-shaped lines of stakes, woven panels, and a large wicker trap. They show that people used passive fishing methods on the river.

The Domesday Book (an old survey) showed many successful mills and fisheries along the Trent. Mills were important places for fish and eel traps. Eels were caught in late summer. Records from the 1100s show that landlords were paid in salmon instead of rent at Burton upon Trent.

In the 1600s, Izaak Walton called the River Trent "one of the finest rivers in the world." He said it had "excellent salmon and all sorts of delicate fish." A list from 1641 for the Trent had thirty types of fish. These included fish that migrated from the sea like shad, smelt, salmon, and flounder. It also had river fish like trout, grayling, perch, and pike.

The largest fish listed was the sturgeon. At one time, sturgeon were caught in the Trent as far upstream as King's Mill, but not many. Some examples include an 8 feet (2.4 m) one caught in 1255 and a 7 feet (2.1 m) one in 1791. The last known catch was in 1902 near Holme. This fish was 8+1⁄2 feet (2.6 m) long and weighed 250 pounds (110 kg).

Pollution from factories and waste in the early 1900s caused fish numbers to drop quickly. Large parts of the river had no fish, and species like salmon almost disappeared. As water quality improved from the 1960s onwards, fish numbers recovered. Recreational coarse fishing (fishing for non-salmon fish) became more popular.

By the 1970s, anglers (people who fish with a rod) thought the Trent was "one of the most productive rivers in the British Isles." Anglers would travel from South Yorkshire and other areas to fish the Trent. This was because their local rivers were still very polluted and had no fish.

A study of fishing records from 1969 to 1985 showed that the most caught fish were barbel, bream, bleak, carp, chub, dace, eel, gudgeon, perch, and roach. The study showed a change in the types of fish caught. There was a shift from roach and dace to chub and bream. Anglers felt this was a "serious harm" to the fishery. This led to comments that the river had become "too clean for its fish." Its popularity, especially for fishing competitions, went down from the mid-1980s. Competition from other fishing spots, like well-stocked ponds and lakes, also made fishing the Trent less appealing.

Recreational fishing is still popular, though not as many anglers line the banks as before. Many fishing clubs use the river. Catches include barbel, bream, carp, chub, dace, pike, and roach.

Salmon, a species that almost disappeared due to old pollution, have been brought back to the smaller rivers since 1998. Thousands of young salmon are released into the Dove and its river Churnet each year. Adult salmon have been seen jumping over weirs on the river. In 2011, a large salmon weighing over 10 pounds (4.5 kg) was caught. It was thought to be the biggest caught on the Trent in 30 years.

Places Along the Trent

Cities and towns on or close to the river include:

- Stoke-on-Trent

- Stone

- Rugeley

- Burton upon Trent

- Castle Donington

- Long Eaton

- Beeston

- Nottingham

- Newark-on-Trent

- Gainsborough

Crossing the Trent

Before the mid-1700s, there were few permanent ways to cross the river. Only four bridges existed downstream of where the Tame river joins: old medieval bridges at Burton, Swarkestone, Nottingham (called Hethbeth Bridge), and Newark. All were built by 1204.

However, there were over thirty ferries operating along its path. Also, many fords (shallow places to walk across) allowed passage. Their locations are often shown by "ford" in place names like Hanford and Wilford.

In 1829, it was noted that all three types of crossings were still used in the Derbyshire part of the Trent. But the fords were old and dangerous. These fords only allowed crossing when water levels were low. When the river flooded, a long detour was needed. They could be risky for those who didn't know them. There were few gauges to show if the river was too deep. They were rarely used except by locals. One of the earliest known fords was at Littleborough. The Romans built it with flat stones and strong wooden posts. The importance of these fords was shown in a 1783 law. It limited dredging at these sites so they stayed less than 2 feet (0.61 m) deep.

Ferries often replaced these older fording points. They were essential where the water was too deep, like the tidal section of the lower river. Since they made money, they were recorded in the Domesday Book at places like Weston on Trent and Fiskerton. Both were still running in the mid-1900s. The ferry boats on the Trent varied in size. They ranged from small rowing boats to flat-decked boats that could carry animals, horses, and even carts.

Bridges over the river were built in Saxon times at Nottingham. For a while, there was also one north of Newark at Cromwell. These bridges became important centers for trade and military. King Edward fortified the Nottingham bridge in 920. Important battles took place at Burton's bridge in 1322 and 1643. The medieval bridges of Burton and Nottingham lasted until the 1860s when they were replaced. The middle arches of the medieval Swarkestone bridge were destroyed by the great flood of 1795 and rebuilt. But because it was in a more rural area, large parts of the medieval bridge still exist and are used today. This bridge is almost one mile (1.6 km) long, crossing a wide floodplain. This was a huge project to let flood waters pass under it. At Newark, the last bridge on the Trent until modern times, was rebuilt in 1775.

At least one other medieval attempt was made to bridge the Trent near Wilden at Hemington. But this bridge was gone long before the end of the Middle Ages. The remains of three bridges show attempts to keep a crossing open for over two hundred years from 1097. These bridges were destroyed by erosion, floods, and the river changing its course. The bridge was probably gone by about 1311. That's when the nearby Wilden ferry was first recorded. The site then had no bridge until Cavendish Bridge opened around 1760. Since no old records mention the Hemington bridge, there might have been other medieval bridge projects now forgotten.

Cavendish Bridge itself was badly damaged by a flood in March 1947. A temporary Bailey bridge had to be used until a new concrete bridge was built in 1957.

When bridge building started again, toll bridges were often built where ferries used to be. This happened at Willington, Gunthorpe, and Gainsborough.

At Stapenhill near Burton, people also wanted a new bridge. A count showed that the foot ferry was used 700 times a day. The new Ferry Bridge opened in 1889. But it needed money from a rich brewer, Michael Bass, to be built. Later, in 1898, he bought the ferry rights so the bridge became free to cross.

Most of the toll bridges were bought by county councils in the 1800s. One of the first was Willington in 1898. The first day it was free was celebrated with a procession across the bridge. The only toll bridge left across the Trent is at Dunham. However, it is free to cross on Christmas and Boxing Day.

Power Stations

The tall chimneys and curved cooling towers of many power stations are a common sight in the Trent valley. This area has been widely used for generating electricity since the 1940s.

The main reason for building so many power stations by the Trent was the large amount of cooling water available from the river. This, combined with nearby coal supplies from Nottinghamshire and Yorkshire, and existing railway lines, led to twelve large power stations being built along its banks. At one time, these sites provided a quarter of the UK's electricity. This earned the area the nickname 'Megawatt Valley'.

When these early power stations reached the end of their useful life, they were usually torn down. But in some cases, the sites have been kept and rebuilt as gas-fired power stations.

In order downstream, the power stations that used the river for cooling water are: Meaford, Rugeley, Drakelow, Willington, Castle Donington, Ratcliffe-on-Soar, Wilford, Staythorpe, High Marnham, Cottam, West Burton, and Keadby.

There is one hydroelectric power station (which uses water to make electricity) on the river, Beeston Hydro at Beeston Weir.

Fun on the Trent

Like other major rivers in the Midlands, the Trent is used for many fun activities. These happen both on the water and along its banks. The National Watersports Centre at Holme Pierrepont, near Nottingham, has facilities for many sports. These include rowing, sailing, and whitewater canoeing.

The Trent Valley Way is a long walking path created in 1998. It lets walkers enjoy the river's natural beauty and its history as a waterway. Extended in 2012, the path now runs from Trent Lock in the south to Alkborough, where the river meets the Humber. It includes sections along the river and towpaths, as well as paths to villages and interesting places in the wider valley.

Historically, swimming in the river was popular. In 1770, Nottingham had two swimming areas at Trent Bridge. These were improved in 1857 with changing sheds. Similar facilities were present in 1870 at Burton-on-Trent, which also had its own swimming club. Open water swimming still happens at places like Colwick Park Lake, next to the river. It even has its own volunteer lifeguards. The first person to swim the entire swimmable length of the Trent was Tom Milner. He swam 139 miles (224 km) over nine days in July 2015.

Rowing clubs have existed at Burton, Newark, and Nottingham since the mid-1800s. Various regattas (rowing races) take place between them. These happen both on the river and on the rowing course at the national watersports center.

Both whitewater and flat water canoeing are possible on the Trent. There are guides and routes published for the river. There's a canoe slalom course at Stone. A special 700 m (2,300 ft) artificial course is at Holme Pierrepont. Various weirs, including those at Newark and Sawley, are used for whitewater paddling. Many canoe and kayak clubs paddle on the river, including those at Stone, Burton, and Nottingham.

The Trent Valley Sailing Club, started in 1886, is one of two clubs that use the river for dinghy sailing, regattas, and events. There are also clubs that sail on the open water created by flooded gravel pits. These include Hoveringham, Girton, and Attenborough.

Organized trips on cruise boats have long been a feature of the Trent. At one time, steam boats took passengers from Trent Bridge to Colwick Park. Similar trips run today, but in reverse. They start from Colwick and pass through Nottingham, using boats called the Trent Princess and Trent Lady. Other trips run from Newark castle. Two converted barges, the Newark Crusader and Nottingham Crusader, offer river cruises for disabled people through a special scheme.

Rivers Joining the Trent

Even though the poet Spenser said the "beauteous Trent" had "thirty different streams," the river is actually joined by more than twice that number. The largest river joining it, in terms of water flow, is the Tame. This river drains most of the West Midlands, including Birmingham and the Black Country. The second and third largest are the Derwent and the Dove. Together, these two rivers drain most of Derbyshire and Staffordshire, including the high areas of the Peak District.

The River Soar, which drains most of Leicestershire, could also be considered the second largest. It has a bigger area that it drains than the Dove or Derwent. But its water flow is much less than the Derwent, and also less than the Dove.

In terms of rainfall, the Derwent basin gets the most rain each year. The Devon basin, which has the lowest average rainfall, is the driest of those listed.

| Statistics of the Trent's largest tributaries | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | County | Length | Catchment Area | Discharge | Rainfall | Max. Altitude | Refs | |||||

| km | mi | km2 | mi2 | m3/s | cfs | mm | in | m | ft | |||

| Blithe | 47 | 29 | 167 | 64 | 1.16 | 41 | 782 | 30.8 | 281 | 922 | ||

| Devon | 47 | 29 | 377 | 146 | 1.57 | 55 | 591 | 23.3 | 170 | 560 | ||

| Derwent | 118 | 73 | 1,204 | 465 | 18.58 | 656 | 982 | 38.7 | 634 | 2,080 | ||

| Dove | 96 | 60 | 1,020 | 390 | 13.91 | 491 | 935 | 36.8 | 546 | 1,791 | ||

| Erewash | 46 | 29 | 194 | 75 | 1.87 | 66 | 708 | 27.9 | 194 | 636 | ||

| Greet | 18 | 11 | 66 | 25 | 0.30 | 11 | 655 | 25.8 | 153 | 502 | ||

| Idle | 55 | 34 | 896 | 346 | 2.35 | 83 | 650 | 26 | 205 | 673 | ||

| Leen | 39 | 24 | 124 | 48 | 0.67 | 24 | 686 | 27.0 | 185 | 607 | ||

| Soar | 95 | 59 | 1,386 | 535 | 11.73 | 414 | 641 | 25.2 | 272 | 892 | ||

| Sow | 38 | 24 | 601 | 232 | 6.33 | 224 | 714 | 28.1 | 234 | 768 | ||

| Tame | 95 | 59 | 1,500 | 580 | 27.84 | 983 | 691 | 27.2 | 291 | 955 | ||

| Torne | 44 | 27 | 361 | 139 | 0.89 | 31 | 615 | 24.2 | 145 | 476 | ||

List of Rivers Joining the Trent

Here is an alphabetical list of rivers that join the Trent:

| Tributary | River Order | Joins Trent at | Bank |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adlingfleet Drain | 1 | Adlingfleet | Left |

| Amerton Brook | 60 | Shirleywich | Left |

| River Blithe | 55 | Nethertown | Left |

| Bottesford Beck | 8 | East Butterwick | Right |

| Bourne Brook | 54 | Kings Bromley | Right |

| Catchwater Drain | 16 | West Burton | Left |

| Causeley Brook | 68 | Hanley | Left |

| Causeway Dyke | 31 | Bleasby | Left |

| Chitlings Brook | 66 | Hanford | Left |

| Cuttle Brook | 42 | Swarkestone | Left |

| Cocker Beck | 33 | Gunthorpe | Left |

| Darklands Brook | 48 | Drakelow | Right |

| River Devon | 27 | Newark | Right |

| River Derwent, Derby | 40 | Shardlow | Left |

| River Dove | 47 | Newton Solney | Left |

| Dover Beck | 32 | Caythorpe | Left |

| River Eau | 9 | Barlings, Scotter | Right |

| River Erewash | 38 | Attenborough | Left |

| Eggington Brook | 46 | Willington | Left |

| Fairham Brook | 37 | Clifton Bridge | Right |

| Ferry Drain | 11 | Owston Ferry | Left |

| Fledborough Beck | 22 | Fledborough | Left |

| Folly Drain | 6 | Althorpe | Left |

| Ford Green Brook | 69 | Milton | Right |

| Fowlea Brook | 67 | Stoke | Right |

| Gayton Brook | 61 | Weston | Left |

| Grassthorpe Beck (Goosemoor Dyke) | 24 | Grassthorpe | Left |

| River Greet | 29 | Fiskerton | Left |

| Healeys Drain | 7 | Burringham | Right |

| Holme Dyke (Bleasby) | 30 | Bleasby | Left |

| River Idle, Nottinghamshire | 13 | West Stockwith | Left |

| Laughton Drain | 10 | East Ferry | Right |

| River Leen | 36 | Wilford | Left |

| Longton Brook | 63 | Trentham | Left |

| Lyme Brook | 65 | Hanford | Right |

| Marton Drain | 18 | Marton | Right |

| River Mease | 50 | Croxall | Right |

| Milton Brook | 43 | Ingleby | Right |

| Moreton Brook | 57 | Rugeley | Left |

| Morton Warping Drain | 14 | Gainsborough | Right |

| North Beck | 20 | Church Laneham | Left |

| Old Trent (High Marnham) | 23 | High Marnham | Left |

| Ouse Dyke | 34 | Stoke Bardolph | Left |

| Park Brook | 64 | Trentham | Right |

| Pauper's Drain | 3 | Amcotts | Left |

| Polser Brook | 35 | Radcliffe on Trent | Right |

| Pyford Brook | 52 | Alrewas | Right |

| Ramsley Brook | 41 | King's Newton | Right |

| Repton Brook | 45 | Repton | Right |

| Rising Brook | 58 | Rugeley | Right |

| Rundell Dyke | 28 | Averham | Left |

| Scotch Brook | 62 | Stone | Left |

| Sewer Drain | 19 | Torksey | Right |

| Sewer Dyke (North Clifton) | 21 | North Clifton | Right |

| Seymour Drain | 17 | Cottam | Left |

| Shropshire Brook | 56 | Longdon / Armitage | Left |

| River Soar, Leicester | 39 | Trentlock | Right |

| River Sow | 59 | Great Haywood | Right |

| River Swarbourn | 53 | Wychnor | Left |

| River Tame | 51 | Alrewas | Right |

| Tatenhill Brook | 49 | Branston | Left |

| The Beck (Carlton on Trent) | 26 | Carlton on Trent | Left |

| The Fleet | 25 | Girton | Right |

| River Torne | 5 | Keadby | Left |

| Twyford Brook | 44 | Twyford | Left |

| Warping Drain (Keadby) | 4 | Keadby | Left |

| Warping Drain (Owston Ferry) | 12 | Owston Ferry | Left |

| Wheatley Beck | 15 | West Burton | Left |

| Winterton Beck | 2 | Bole Ings | Right |

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Río Trent para niños

In Spanish: Río Trent para niños

- List of rivers of Great Britain

- Trent River Authority

- Trent Valley Line

- Trent Valley Way

- List of fish in the River Trent

- List of crossings of the River Trent

- Trent River (Ontario)

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |