American mink facts for kids

Quick facts for kids American mink |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Near Capisic Pond, Portland, Maine | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Mustelidae |

| Genus: | Neogale |

| Species: |

N. vison

|

| Binomial name | |

| Neogale vison (Schreber, 1777)

|

|

| Subspecies | |

|

15, see text

|

|

|

|

| American mink range in North America | |

|

|

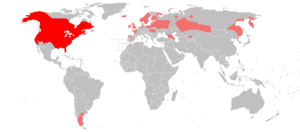

| Native (red) and introduced (pink) range of American mink | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The American mink (Neogale vison) is a furry animal that lives near water. It is part of the weasel family. These animals are originally from North America. However, people have brought them to many parts of Europe, Asia, and South America.

Because they have spread so much, the American mink is listed as a least-concern species by the IUCN. This means they are not currently in danger of disappearing. The American mink is a carnivore, which means it eats meat. Its diet includes small animals like rodents, fish, crabs, frogs, and birds.

In Europe, where it was introduced, the American mink is seen as an invasive species. This means it can harm local wildlife. It has been linked to declines in populations of the European mink and water vole. The American mink is also the most common animal raised on farms for its fur.

Contents

About the American Mink

How the American Mink Evolved

The American mink is a more specialized hunter than the European mink. This is shown by its stronger skull. Fossils of the American mink have been found from a long time ago, but they are not very common. Ancient American minks were similar in size and shape to the ones we see today.

Even though they look alike, the European mink is actually more closely related to the Siberian weasel. American minks can breed with European minks and polecats in zoos, but their babies usually don't survive.

Subspecies of American Mink

As of 2005, there are 15 known types, or subspecies, of American mink. Each one has slightly different features and lives in different areas.

| Subspecies | Where it Lives | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Eastern or little black mink N. v. vison |

Eastern Canada and parts of northern New York and Pennsylvania. | This is the smallest type of American mink. |

| California lowland mink N. v. aestuarina |

Lowlands of west-central California. | Smaller and has lighter, less thick fur. |

| N. v. aniakensis | ||

| Western or Pacific mink N. v. energumenos |

Western North America, from British Columbia south to the Sierra Nevada and Rocky Mountains. | Small and dark, with sooty-brown fur. Males are about 61 cm (24 inches) long. |

| N. v. evagor | ||

| Everglades mink N. v. evergladensis |

The southern tip of Florida. | |

| Alaskan mink N. v. ingens |

Northern, western, and central Alaska; northern Yukon. | The largest type, but lighter in color. Males are about 73 cm (28.8 inches) long. |

| Hudson Bay mink N. v. lacustris |

Interior of Canada, from Great Bear Lake south through Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. | Dark chocolate-brown fur with white on the chin and chest. Males are about 69 cm (27 inches) long. |

| Mississippi Valley mink N. v. letifera |

Northern Wisconsin and South Dakota south to northern Illinois and Missouri. | Light brown fur with white spots on the chin, throat, and chest. Males are about 66 cm (26 inches) long. |

| N. v. lowii | ||

| Florida mink N. v. lutensis |

Coasts of the southeastern United States from South Carolina to Florida. | Medium-sized with pale reddish-brown fur. Males are about 58 cm (23 inches) long. |

| Kenai mink N. v. melampeplus |

The Kenai Peninsula and Cook Inlet. | Darker than other types, with dark chocolate fur and a white spot on the chin. Males are about 71 cm (28 inches) long. |

| Common mink N. v. mink |

The Eastern United States, from New England south to North Carolina and west to Missouri. | Larger and stronger than the Eastern mink, with similar colors. Males are about 65 cm (25.5 inches) long. |

| Island mink N. v. nesolestes |

Admiralty Island in the Alexander Archipelago. | Medium-sized with dark fur, lighter on the cheeks. Males are about 62 cm (24.5 inches) long. |

| Southern mink N. v. vulgivaga |

Coasts of Louisiana and Mississippi. | Similar to the Common mink but paler and smaller. Males are about 62 cm (24.5 inches) long. |

Physical Description

Body Shape

The American mink is larger and stronger than other weasels. It has a long, bushy tail, similar to a marten. Its tail is also longer than that of the European mink.

Its long, thin body helps it enter the burrows of its prey. Its streamlined shape helps it move easily through water. The skull is strong and wide.

Wild minks have larger brains, hearts, and spleens than minks raised on fur farms. Their feet are wide and have webbing between the toes. This helps them swim.

Male minks are usually 34–45 cm (13–18 inches) long. Females are 31–37.5 cm (12–15 inches) long. Their tails add another 15.6–24.7 cm (6–9.7 inches). Males are heavier than females, especially in winter.

Fur

The American mink's winter fur is thick, long, and soft. It is usually a very dark brown to light brown color. The fur is the same color all over its body, with the underside being only slightly lighter. The tail is darker than the body, sometimes completely black at the tip.

The chin and lower lip are white. Minks raised in captivity sometimes have white patches on their bellies. The summer fur is shorter and less thick. The thick underfur and oily guard hairs make their coat waterproof.

Minks shed their fur twice a year, in spring and autumn. Their fur does not turn white in winter. Many different fur colors have been created through breeding on fur farms.

How They Move

On land, the American mink moves by jumping, reaching speeds of up to 6.5 km/h (4 mph). They can also climb trees and are excellent swimmers. When swimming, they move their body in wavy motions.

When they dive underwater, their heart rate slows down. This helps them save oxygen. In warm water, a mink can swim for 3 hours without stopping. In cold water, it can die in less than half an hour. They usually dive about 30 cm (12 inches) deep for 10 seconds. They can dive up to 3 meters (10 feet) deep for 60 seconds. They often catch fish after chasing them for 5 to 20 seconds.

Senses and Scent Glands

American minks use their sight a lot when looking for food. They see better on land than underwater. They can hear very well, even the high-pitched sounds of rodents. Their sense of smell is not as strong.

They have two anal glands that they use for scent marking. These glands produce a strong smell. Some people have described the smell as very unpleasant.

Behavior

Social Life and Territory

American minks live alone and have their own territories. Male and female territories can overlap, but minks of the same sex usually don't share space. They prefer rocky coastal areas with lots of hiding spots near water. Some live near cities, along rivers and canals.

Their home areas are usually 1–6 km (0.6–3.7 miles) long. Male territories are larger than female ones. Minks are not picky about where they make their dens, as long as it's near water. Dens are often long tunnels in river banks, holes under logs, tree stumps, or roots. They also use rock cracks, drains, and spaces under bridges.

The burrows they dig are about 10 cm (4 inches) wide and can be 3–3.7 meters (10–12 feet) long. They are usually 60–90 cm (2–3 feet) deep. Minks might also use old burrows dug by muskrats, badgers, or skunks. The nesting area is at the end of a tunnel, about 30 cm (1 foot) wide. It is warm and dry, lined with straw and feathers. Mink dens often have many entrances, from one to eight.

Minks usually only make sounds when they are close to other minks or predators. They can shriek and hiss when scared. They make soft chuckling sounds when mating. Baby minks squeak when they are away from their mothers. When feeling threatened, minks might arch their backs, puff up their fur, lash their tails, and stomp their feet. They also open their mouths wide to show their teeth. If this doesn't work, they might fight, often injuring each other's heads and necks.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

American minks do not stay with one partner. The mating season starts in February in warmer areas and April in colder ones. In places where they have been introduced, they breed earlier than European minks. Males often fight during this time to get access to females.

The mating season lasts for three weeks. Females are ready to mate for 7–10 days during this period and can mate with several males. The mating process can be rough, with the male biting the female's neck. Mating can last from 10 minutes to four hours.

Minks have a special ability called delayed implantation. This means the fertilized eggs don't immediately attach to the womb. This allows the female to wait for the best time and place to give birth. The total gestation period (pregnancy) is 40 to 75 days. However, the babies only develop for 30–32 days.

Young minks are born from April to June. A litter usually has four babies, called kits. Sometimes, litters can be much larger, with up to 16 kits. Kits are born blind, weighing only 6 grams (0.2 ounces). They have a short coat of fine, silver-white hairs.

Kits drink their mother's milk. Their eyes open after about 25 days. They stop drinking milk after five weeks. Kits start hunting when they are about 8 weeks old. They stay with their mother until autumn, when they become independent. They can start having their own babies when they are about 10 months old.

Diet

The American mink is a meat-eating animal. It eats rodents, fish, crustaceans (like crabs), amphibians (like frogs), and birds. It kills its prey by biting the back of the head or neck. The bite marks are usually 9–11 mm (0.35–0.43 inches) apart. Minks often drown birds, even large ones like seagulls.

In its natural home, fish are its main food. Minks are good at hunting muskrats. They chase them underwater and kill them in their burrows. They also eat many types of rats and mice. In swampy areas, they often catch Marsh rabbits.

In other parts of the world where they have been introduced, their diet changes. In Russia, they eat voles, fish, crabs, frogs, and water insects. In winter, they eat more water-based foods. In spring, they eat more land animals. In the British Isles, they mostly eat European rabbits, fish, and birds like moorhens and coots. They also eat crabs and crayfish.

American minks are known to cause problems for water voles and waterfowl in Europe. They are sometimes hunted in Europe to control their numbers. In South America, they mainly eat mammals and birds.

Minks can sometimes attack poultry (farm birds). However, they usually kill and eat only one bird at a time. Studies in Britain show that farm birds make up only 1% of their diet. Small mammals, fish, and wild birds are much more common in their diet.

Relationships with Other Predators

The American mink often takes over areas where European minks live. They can even kill European minks. The number of European minks has gone down as American minks have spread.

American minks and European otters eat many of the same foods. Where they live in the same areas, minks might hunt more land animals because otters are better at catching fish.

Large birds of prey, like bald eagles and great horned owls, sometimes hunt American minks. In Finland, white-tailed eagles help control the mink population by hunting them.

Intelligence

A study in the 1960s looked at how well minks, ferrets, skunks, and house cats learned visually. Minks were better at recognizing objects and remembering them than the other animals.

Range

Natural Home

The American mink naturally lives across most of North America. This includes Alaska, Canada, and much of the United States. They are not found in very dry areas like Arizona and parts of California and Nevada.

Introduced Areas

South America

American minks were brought to Patagonia, Argentina, in 1930 for fur farming. They escaped or were released and now live in several provinces. In Argentina, they are a big threat to the Hooded grebe, a bird that is close to extinction.

In Chile, American minks were introduced in the 1930s. After the fur industry declined, they spread across Chile. They have even been found on the Chiloé Archipelago, possibly arriving by ship.

Western Europe

Wild American minks in Europe likely came from fur farms. The first ones were brought to Europe in 1920. In Italy, they were introduced in the 1950s and now live mostly in the northeast.

In Spain, escaped minks created their own populations. In 2013, the Spanish government planned to remove them to protect local animals like the European mink.

Norway's first mink farm was built in 1927. Within 30 years, escaped minks started wild populations. By 1965, minks had spread across most of Norway. Today, they live everywhere on the mainland but are absent from some islands.

American minks were first brought to Great Britain in 1929. Escapes led to wild populations by the late 1950s. In Ireland, wild populations started later, in the 1950s. Minks are now common in Great Britain and Ireland. The mink population in Great Britain is estimated at 110,000. This number might be going down as European otter numbers increase.

Former USSR

In 1933, American minks were released in European Russia. More minks were released in many parts of the Soviet Union until 1963. This included areas in Russia, Karelia, and the Baltic states. They were also released in Siberia and the Far East. Even though they spread widely, their populations were often isolated.

Iceland

Minks have been in Iceland since the 1930s and are well-established. They have been hunted a lot since 1939. However, their population dropped by 42% between 2002 and 2006. This happened when the number of sand eels, which minks eat, also went down.

Diseases and Parasites

American minks can get tick and flea infestations. They can also have internal parasites.

Transmissible mink encephalopathy (TME) is a brain disease in minks. It is similar to mad cow disease in cattle. An outbreak in 1985 caused 60% of the minks to die. This disease can spread between minks, cattle, and sheep.

A parasite called Toxoplasma gondii has been found in American minks in southern Chile. This shows that minks in that area are often exposed to this parasite.

Decline of Wild Mink

When domestic minks escape from fur farms, they can cause problems for wild mink populations. Farmed minks are larger than wild minks. Minks are solitary and territorial. If too many minks are in one area, they might fight or starve.

When many farmed minks are released, it can disturb the wild minks. Many of the released minks die from starvation or injuries from fighting. If a farmed mink survives and breeds, it can mix its genes with wild minks. Some believe this has made wild mink populations weaker in Canada.

A study in Denmark in 2006 found that most "wild" minks were actually escapees from fur farms. About 47% had escaped recently. If these escaped minks survive for at least two months, they have the same survival rate as wild minks. This suggests they quickly adapt to living in the wild.

Relationships with Humans

Diseases from Minks

Both American and European minks have been found to carry SARS-CoV-2. This is the virus that causes COVID-19.

Fur Use

American mink fur is mainly used to make fur coats, jackets, and capes. Smaller pieces of fur are used for trimming on clothes. Mink scarves and stoles are also made. The most valuable furs come from eastern Canada.

Trapping

Before mink farming became popular, American minks were often trapped. This was because they don't hibernate in winter, so they could be caught even in cold areas. Minks were usually trapped from November to April when their fur was best. They are very strong and can even break their teeth trying to escape traps.

Native American methods for trapping minks included using bait like chicken filled with fish oil. Another method involved placing traps scented with muskrat and female mink musk near water.

Farming

People started breeding American minks for their fur in the late 1800s. This was because the demand for mink fur was growing. American minks are easy to keep and breed in captivity. In 2005, the U.S. was the fourth largest producer of mink fur.

Minks usually breed in March and have their babies in May. Farmers vaccinate the young minks against common diseases. They are harvested in late November and December. In the past, some farms had pools for minks to swim, but this is rare now. Minks like to swim, so not having water can be frustrating for them. Farmed minks are fed a diet that includes meat and milk.

Color Mutations

Breeding has created many different fur colors in minks. These range from pure white to almost black. The two main types are brown and "black cross." When these are bred together, they create many color variations.

As Pets

Wild minks can be tamed if caught when young. However, they can be hard to handle and are usually not held with bare hands. In the late 1800s, tame American minks were used to catch rats, much like ferrets. Some people still use farmed minks for ratting today. They can be better at catching rats than terrier dogs because they can go into rat holes.

Wild minks usually dominate tame minks when they are together. They have also been known to dominate cats in fights. Minks are intelligent, but they don't learn tricks easily. Because they love bathing, captive minks might jump into kettles or other open water containers.

Even though domestic minks have been bred for almost a century, they haven't been bred to be tame. They have been bred for their size, fur quality, and color. However, some groups claim that minks are truly domesticated animals because they have been kept on farms for so long.

Minks in Stories

As an invasive species in the United Kingdom, minks have appeared in at least two novels. Ewan Clarkson's 1968 book Break for Freedom tells a realistic story of a female mink escaping a fur farm. On the other hand, A.R. Lloyd's 1982 book Kine is a fantasy story where minks are the bad guys and weasels are the heroes.

Indigenous Names

- Abenaki language

- Western Abnaki: mosbas

- Penobscot: mósəpehso

- Alabama: sakihpa

- Aleut: ilgitux̂

- Arapaho: no'eihi'

- Arikara: eérux

- Assiniboine: íkusana

- Blackfoot: aapssiiyai'kayi or soyii'kayi

- Cherokee: svki

- Chickasaw: okfincha

- Chipewyan: tthełjus

- Comox: qayχ

- Cree: sâkwes

- Plains Cree: sâkwês ᓵᑫᐧᐢ

- Swampy Cree: šâkwêšiw ᔖᑴᔑᐤ

- Moose Cree: shakweshiw ᔕᑴᔑᐤ

- Naskapi: achikaas ᐊᒋᑲᔅ

- Innu: atshakash

- James Bay Cree: achikaash ᐊᒋᑳᔥ

- Crow: baapúxtakbialee

- Dakelh

- Nadleh Whut'en: telhjoos

- Nak'azdli: techus

- Dane-zaa: taadle

- Delaware

- Gitxsan: lis'in

- Halkomelem

- Hul'q'umi'num: chuchi'q'un'

- Halqeméylem: ts'qáyex̱iya

- Heiltsuk-Oowekyala: kvənn̓à

- Haíɫzaqv: kvṇ̓á

- Hidatsa: nagcúa

- Ho-Chunk: jająksík

- Kaska: tets'ūtl'ęhį̄

- Koasati: sa•kih•pa

- Kutenai: ʔinuya

- Kwakiutl: ma̱tsa

- Lakota: ikhúsą

- Lillooet: t̓sexyátsen

- Lushootseed

- Northern Lushootseed: bəščəb

- Southern Lushootseed: c̓əbal̕qid

- Malecite-Passamaquoddy: ciyahkehs

- Menominee: sāhkih

- Miami-Illinois: šinkohsa

- Miꞌkmaq: mujpej

- Nisga'a: lisy̓een

- Nishnaabemwin: zhaangwesh

- Nlaka'pamuctsin: c̓əx̣lécn

- Nuxalk: t'uka

- Nuu-chah-nulth

- Ehattesaht: č̕aastumc

- Tseshaht: č̓aastimc

- Ojibwe: zhaangweshi

- Okanagan: c̓x̌licn

- Omaha–Ponca: íki skă

- Oneida: shotsya·káweˀ

- Potawatomi: wnepshkwé

- Salish: c̓xlicn̓

- Senćoŧen: ćećiḵen

- Shashishalhem: ḵáyx̱

- Secwepemc: ts'exlétsen

- Sm'álgyax: lis'yaan

- Tuscarora: θenę́·ku·t

- Tse'khene: tantl'ehe

- Umatilla: kuucpúu

- Witsuwittʼen: tëc'ohts'iy

See also

- Aleutian disease

- European mink

- Sea mink

- Fur farming

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |