Bridgewater Canal facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Bridgewater Canal |

|

|---|---|

The Packet House at Worsley, on the canal

|

|

| Specifications | |

| Length | 41 miles (66 km) |

| Maximum boat length | 72 ft 0 in (21.95 m) |

| Maximum boat beam | 14 ft 9 in (4.50 m) |

| Locks | 0 (originally 10 at Runcorn) (See article) |

| Original number of locks | 10 at Runcorn |

| Status | Open |

| Navigation authority | Peel Holdings |

| History | |

| Principal engineer | John Gilbert, James Brindley |

| Date of act | 1759, 1760, 1762, 1766, 1795 |

| Date of first use | 1761 |

| Date completed | 1761 |

| Date extended | 1762 |

| Geography | |

| Start point | Worsley |

| End point | Runcorn (originally Manchester) (See article) |

| Connects to | Rochdale Canal, Trent and Mersey Canal, Leeds and Liverpool Canal, Manchester Ship Canal |

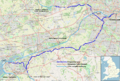

The Bridgewater Canal is a famous waterway in North West England. It links the towns of Runcorn, Manchester, and Leigh. This canal was built for Francis Egerton, 3rd Duke of Bridgewater. His main goal was to move coal from his mines in Worsley to the growing city of Manchester.

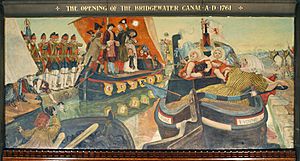

The canal first opened in 1761, connecting Worsley to Manchester. Later, it was made longer, reaching Runcorn and then Leigh. The Bridgewater Canal connects to several other important waterways. These include the Manchester Ship Canal, the Rochdale Canal, the Trent and Mersey Canal, and the Leeds and Liverpool Canal.

Many people call the Bridgewater Canal the first great achievement of the "canal age." Even though the Sankey Canal opened earlier, the Bridgewater Canal really caught people's attention. It had amazing engineering feats, like an aqueduct that carried boats over the River Irwell. It also had special tunnels at Worsley. The canal's success helped start a time of huge canal building in Britain, known as Canal Mania. Today, the canal is still used by boats, mostly for fun. It is also part of the Cheshire Ring network of canals.

Contents

Building the Canal

Francis Egerton, 3rd Duke of Bridgewater, owned many coal mines. These mines supplied fuel for the steam engines used during England's Industrial Revolution. The Duke moved his coal using rivers or packhorses. But these ways were slow and costly. River travel depended on the weather, and horses could only carry so much coal. Also, his underground mines often flooded because of the ground's geology.

The Duke had seen canals in France and England. He decided to build an underground canal at Worsley. This canal would connect to a surface canal going from Worsley to Salford and Manchester. This plan would make it easier to move coal and help drain his mines. It also meant coal didn't need to be lifted to the surface, which was hard and expensive. Canal boats could carry 30 tons of coal, pulled by just one horse. This was much more than horses could carry in carts.

The Duke and his manager, John Gilbert, drew up a plan. In 1759, they got permission from Parliament to build it.

James Brindley was a skilled engineer. He was asked to help with the project. After looking at the area, he suggested changing the canal's path. Instead of going to Salford, it would cross the River Irwell to Stretford and then into Manchester. This new route would make it easier to connect to other canals later. It would also create competition with the existing Mersey and Irwell Navigation company.

Brindley surveyed the new route. To cross the Irwell, a large aqueduct was needed at Barton-upon-Irwell. The Duke got a second Act of Parliament in 1760 for this new route.

Brindley's plan started at Worsley. It went southeast through Eccles, then south to cross the River Irwell on the Barton Aqueduct. From there, it continued to Manchester. The canal ended at Castlefield Basin, where the River Medlock helped supply water. Boats would unload their coal inside the Duke's special warehouse. Brindley's design had no locks, which showed his engineering skill. The Barton Aqueduct was built quickly. Work started in September 1760, and the first boat crossed it on 17 July 1761.

The Duke spent a lot of money on the canal. The section from Worsley to Manchester cost about £168,000. But the canal was so good that within a year of opening in 1761, the price of coal in Manchester dropped by half. This success helped start the "Canal Mania" period. The Bridgewater Canal, with its stone aqueduct, was seen as a huge engineering success. People said it was "the most extraordinary thing in the Kingdom."

The Duke also built warehouses in Manchester. One of his warehouses was damaged by fire in 1789 but was rebuilt.

Manchester to Runcorn

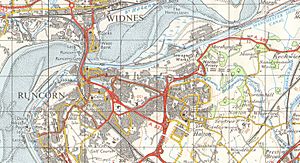

In 1761, Brindley planned an extension of the canal from Manchester to the River Mersey at Runcorn. Despite some objections, Parliament approved the plan in 1762. A new junction was made in Trafford Park. From there, the canal branched south through towns like Stretford and Altrincham, ending at Runcorn.

At Runcorn, the canal was almost 90 feet (27 meters) above the Mersey River. So, a series of ten locks was built to connect them. These locks were considered "the wonder of their time." They allowed boats to move between the canal and the river, no matter the tide. The connection to the Mersey was finished on 1 January 1773.

The river's tides sometimes left mud around the locks. To fix this, a special channel called the Duke's Gut was dug. Gates on this channel would open at low tide to wash away the mud. This created an island called Runcorn Island.

The connection to Manchester was delayed by a landowner, Sir Richard Brooke. He worried that boatmen might hunt on his land. Eventually, a deal was made. This included building a link to the Trent and Mersey Canal at Preston Brook. This link gave the Duke access to the Midlands. The new extension was partly opened in 1767 and fully completed by March 1776. Brindley died before it was finished, and his brother-in-law, Hugh Henshall, continued the work.

The total cost of the canal, from Worsley to Manchester and to Runcorn, was £220,000. At Runcorn, the Duke built a dock, warehouses, and a temporary home for himself.

Worsley to Leigh

In 1795, the Duke got permission to extend the canal another 5 miles (8 km). This extension went from Worsley through places like Boothstown to Leigh. This new part allowed coal from Leigh and nearby areas to be sent to Manchester. In 1819, a link was made between this extension and the Leeds and Liverpool Canal at Wigan.

Having access to the canal helped coal mining grow quickly west of Worsley. Many coal pits connected to the canal, either directly or through underground tunnels. For example, in 1820, the Chaddock Pit was linked to the canal at Boothstown by an underground canal. Later, railways were built to bring coal from other mines to the canal for loading onto barges.

Connection to Rochdale Canal

When the Rochdale Canal was finished in 1804, it joined the Bridgewater Canal at Castlefield. The River Medlock, which supplied water to the canal, was very polluted. So, it was redirected through a tunnel under the canal. From then on, the Bridgewater Canal got cleaner water from the Rochdale Canal.

Mines

Worsley Delph, in Worsley, was the entrance to the Navigable Levels. It was originally a very old sandstone quarry. Special boats, called M-boats or Starvationers, could carry up to 12 tons of coal. Inside the mines, there were 46 miles (74 km) of underground canals on four different levels. These levels were connected by ramps. The mines stopped producing coal in 1887. For many years, the water in the canal near Worsley has been stained bright orange by iron oxide from the mines. There is now a project to clean up this color.

Canal Traffic

In 1791, the Worsley mines produced over 100,000 tons of coal. A large part of this was sold and moved by the canal. About 12,000 tons of rocksalt from Cheshire was also transported. The canal earned money from coal sales and other goods. It also carried passengers, bringing in over £3,700 in 1791.

The canal was very popular for passenger travel. It competed with the Mersey and Irwell Navigation Company. The journey on the Bridgewater Canal took about nine hours each way. People said it was "more picturesque" than other routes.

At first, horses pulled the barges on the canal. But in the mid-1800s, a disease spread among the horses. So, steam-powered boats started to be used instead. Some local people didn't like the "dense smoke" and "harsh unnecessary whistling" from these steam barges.

The canal carried commercial goods until 1975. The last regular cargo was grain. Today, the canal is mainly used by people for fun, like boating. It is also home to two rowing clubs.

Canal Management

When the Duke of Bridgewater died in 1803, the canal's income went to his nephew, George Leveson-Gower, 1st Duke of Sutherland. The canal was managed by three trustees. These included Robert Haldane Bradshaw, who was the Duke's agent and managed the canal day-to-day.

Under the Bridgewater Trustees, the canal made a profit every year. Between 1806 and 1826, the average yearly profit was about 13 percent. In 1824, it reached 23 percent. Bradshaw was known for being a tough negotiator.

In the 1820s, people started to be less happy with canals. They couldn't handle all the goods, and some felt they were monopolies. People became more interested in building railways. Bradshaw strongly opposed building a railway between Liverpool and Manchester. He refused to let railway surveyors onto land owned by the Trustees.

However, in 1825, Lord Stafford (the Duke's nephew) invested £100,000 in the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. After this, the Trustees stopped opposing the railway, and it was approved in 1826. At the same time, Lord Stafford gave £40,000 for improvements to the canal. This money was used to build a second set of locks at Runcorn, finished in 1828, and new warehouses.

In 1830, the new railway opened and started carrying goods. Bradshaw immediately lowered the canal's prices to compete. This helped the canal keep its traffic, but it also caused profits to drop. More competition came from the Macclesfield Canal, which opened in 1831.

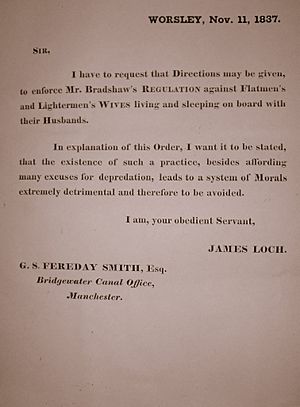

In 1837, James Loch became the Superintendent. He reorganized the canal's business and improved passenger services. By 1837, the Trustees employed about 3,000 people, making them one of the country's largest employers. Since the Duke's death, the amount of goods carried by the canal had almost tripled.

In 1843, a new dock, the Francis Dock, opened at Runcorn. The canal faced strong competition from other canals and railways. In 1844, the Bridgewater Trustees bought the Mersey and Irwell Navigation company to reduce competition. They also made agreements with other canal companies.

The biggest threat then came from the railways during the "Railway Mania" of the mid-1840s. Railways built new lines that competed directly with canals. They also formed large companies and started buying canal companies. In 1844, there was a rumor that the canal would be drained and turned into a railway, but this didn't happen. The Trustees worked hard in Parliament to protect their interests.

In 1855, Algernon Egerton became the Superintendent. He was Lord Ellesmere's son and was only 29. He had little experience with canals. Under his leadership, the canal invested more money in improvements. The Runcorn and Weston Canal was built in 1858–59, connecting Runcorn Docks to the Weaver Navigation. A new dock, the Alfred Dock, opened at Runcorn in 1860. Electric telegraph was installed in 1861–62.

In 1862, the 2nd Earl of Ellesmere died, and his son, the 3rd Earl, was only 15. This gave Algernon Egerton even more power to invest in the company. New docks were built at Runcorn starting in 1867. Improvements were also made to the canal itself and its facilities in Liverpool. Agreements were made with railway companies to work together on moving goods.

Later Owners

In 1872, the Bridgewater Navigation Company Ltd was formed. The canal was sold to Edward Watkin and William Philip Price for £1,120,000. In 1885, the canal was sold again to the Manchester Ship Canal Company for £1,710,000.

Building the Manchester Ship Canal meant that the old Barton Aqueduct had to be removed. It was too low for the new, larger ships. So, the Barton Swing Aqueduct was built instead. This amazing bridge swings open to let ships pass.

In 1923, Bridgewater Estates Ltd was created to own the Ellesmere family's land in Worsley. Later, in 1984, this company was bought by Peel Holdings. Today, the canal is owned by the Peel Ports group, which is part of Peel Holdings.

What's Happening Now

The Bridgewater Canal is still seen as a major achievement from the canal age. It is famous for its engineering, like the aqueduct over the River Irwell and the tunnels at Worsley.

Today, the canal ends at Runcorn basin. The original ten locks that connected it to the River Mersey are no longer used. They were closed and filled in during the 1930s and 1940s. The Duke's warehouse in Manchester was taken down in 1960.

The canal has had a few leaks over the years. When a leak happens, special cranes along the canal can drop boards into slots. This helps to block off sections of the canal and stop the water.

The canal is now a key part of the Cheshire Ring network of canals. Since 1952, boats used for fun and leisure have been allowed on the canal.

A new road bridge is being built over the Mersey. This project might allow the old locks at Runcorn to be fully restored. This would reopen the link to Runcorn Docks, the River Mersey, and the Manchester Ship Canal. It would create a new route for leisure boats.

The Hulme Locks Branch Canal in Manchester is no longer used. It was replaced by the nearby Pomona Lock in 1995.

Bridgewater Way

The Bridgewater Way is a project to improve the canal and make it easier for people to use, especially cyclists. This 40-mile (64 km) project includes a new towpath. It will be part of the National Cycle and Footpath Network as Regional Route number 82.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Canal de Bridgewater para niños

In Spanish: Canal de Bridgewater para niños