Canal Age facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Erie Canal |

|

|---|---|

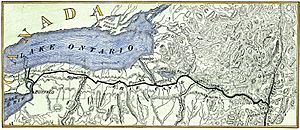

Current Route of the Erie Canal

|

|

| Specifications | |

| Length | 524 miles (843 km) |

| Locks | 36 |

| Maximum height above sea level | 571 ft (174 m) |

| Status | open |

| Navigation authority | New York State Canal Corporation |

| History | |

| Original owner | New York State |

| Principal engineer | Benjamin Wright |

| Other engineer(s) | Canvass White, Amos Eaton |

| Construction began | July 4, 1817 (at Rome, New York) |

| Date of first use | May 17, 1821 |

| Date completed | October 26, 1825 |

| Date restored | September 3, 1999 |

| Geography | |

| Start point | Hudson river near Albany, New York (42°47′00″N 73°40′36″W / 42.7834°N 73.6767°W) |

| End point | Niagara river near Buffalo, New York (43°01′25″N 78°53′24″W / 43.0237°N 78.8901°W) |

| Branch(es) | Oswego Canal, Cayuga–Seneca Canal |

| Branch of | New York State Canal System |

| Connects to | Champlain Canal, Welland Canal |

The Canal Age was a time when canals became super important for moving goods and people. Many parts of the world, from ancient Egypt to Europe, built canals. Canals helped cultures grow and made industry possible. Before steam locomotives became fast, canals were the quickest way to travel long distances. Boats on commercial canals often moved 24 hours a day, pulled by mule teams.

In North America, canals and early railroads often worked together. Canals made it easier to transport goods, and railroads helped connect to places the canals couldn't reach. Two examples of this were:

- The Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company, which mined coal, transported it using the Lehigh Canal, and used it to make iron goods. They also built the nation's second railway, the Summit Hill and Mauch Chunk Railroad, to help move coal.

- The Delaware and Hudson Canal and Delaware and Hudson Gravity Railroad were built to supply New York City with coal.

These canals, along with the Schuylkill Canal, helped provide coal for industries in the early North American Industrial Revolution. Unlike Europe, North America developed canals and industries at the same time.

|

Lehigh Canal

|

|

The Lehigh Canal as seen from Guard Lock 8 & Lockhouse, Island Park Road, Glendon, Northampton County, PA

|

|

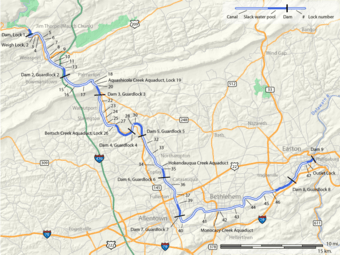

Lower division of the Lehigh Canal, from Jim Thorpe, PA to Easton, PA

|

|

| Location | Lehigh River Upper: Nesquehoning, PA to White Haven, PA Lower: Mauch Chunk (Jim Thorpe) to Delaware River at Easton, PA |

|---|---|

| Built | 1818-1821; 24-27 upper: 1838-1843, Upper ruined & abandoned: 1862 |

| Architect | Canvass White, Josiah White |

| Architectural style | Fitted stone, iron and wood |

| NRHP reference No. | 78002437, 78002439, 79002179, 79002307, 80003553 |

| Added to NRHP | Earliest October 2, 1978 |

Contents

North American Canal Building

Historians say the American Canal Age lasted from about 1790 to 1855. During this time, many new canals were built. Even older canals continued to be used for a long time. The first law to support canals in North America was in Pennsylvania in 1762. It aimed to improve the Schuylkill River for navigation.

One early project was the Union Canal, built in 1828. It connected the Susquehanna River with the Delaware River. Many people, like George Washington and Benjamin Franklin, believed canals were key to America's future.

Pennsylvania was a leader in canal building. It surveyed the first lock canal in America as early as 1762. This canal would run from near Reading on the Schuylkill to Middletown on the Susquehanna.

Energetic men across the Atlantic Plain worked to improve inland rivers. They faced much criticism and ridicule. People worried about engineering problems or even the destruction of fish. But despite these challenges, groups like the Potomac Company (1785) and the Western Inland Lock Navigation Company (1792) were formed. These early efforts show the beginning of water commerce in America.—Archer B. Hurlbert (1920), Chapter III:

Many plans were made in Pennsylvania between 1790 and 1816 to improve rivers like the Susquehanna, Schuylkill, and Lehigh. These plans often failed or made little progress. Meanwhile, the idea for the Erie Canal began in New York State.

By 1855, building railroads became more popular than building canals. Railroads were often cheaper to build and could go more places. Even though moving goods by canal could be cheaper, canals needed a lot of water and regular repairs from ice and floods.

On the eastern coast, cutting down forests caused an energy crisis for cities. But without good water or roads, English coal shipped across the Atlantic was cheaper in Philadelphia than Pennsylvania coal mined 100 miles away. Canals would help both the East and the Midwest. For over a century, canals had offered cheap, reliable transport in Europe. George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and other founding fathers thought they were vital for the New World's future.

—James E. Held, Archeology (journal, July 1, 1998)

Why Canals Were Needed

When the British colonies expanded inland, transportation was a big problem. Moving goods and people between coastal cities and the interior was very hard. This problem existed in many parts of the world where people or animals did most of the moving. Moving things by water was much easier because there was less friction.

Near the coast, rivers often worked well. But the Appalachian Mountains, about 400 miles inland, were a huge challenge. They stretched over 1,500 miles and had only five places where mule trains or wagon roads could pass. Travel overland was slow and difficult due to rough roads. In 1800, it took about 2.5 weeks to travel from New York to Cleveland, Ohio. It took 4 weeks to reach Detroit.

Grain from the Ohio Valley was a main product, but it was cheap and bulky. It often cost too much to transport it to distant cities. This led some farmers to turn their grain into whiskey because it was easier to transport and sell. This also led to the Whiskey Rebellion. People on the coast realized that the city or state that found a cheap way to connect to the West would become very successful.

Early Canal Ideas

Successful canals in Europe, like the Canal du Midi in France (1681), inspired many people. The idea of a canal connecting the East Coast to the western settlements was discussed as early as 1724. Cadwallader Colden, a New York official, mentioned improving waterways in western New York.

Gouverneur Morris and Elkanah Watson were early supporters of a canal along the Mohawk River. Their efforts led to the creation of the Western and Northern Inland Lock Navigation Companies in 1792. This company tried to improve navigation on the Mohawk and build a canal to Lake Ontario. However, private money was not enough for such a big project.

George Washington also worked hard to make the Potomac River a navigable route to the west. He invested a lot of effort and money into the Patowmack Canal from 1785 until his death. By 1788, his company built five locks that helped boats pass the Potomac Great Falls. The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal later replaced this canal in 1823.

The Erie Canal Plan

Jesse Hawley was key to getting the Erie Canal built. He imagined farmers growing lots of grain in Western New York and selling it on the Eastern seaboard. Hawley himself went bankrupt trying to ship grain. While in debtors' prison, he pushed for a canal along the 90-mile Mohawk River valley.

Joseph Ellicott, who sold land in western New York, supported Hawley. He knew a canal would make his land more valuable. Ellicott later became the first canal commissioner.

Building the Erie Canal

The Mohawk River and Hudson River valleys form the only natural path through the Appalachian Mountains north of Alabama. This path allowed for an almost complete water route from New York City to Lake Ontario and Lake Erie. This route could connect a large part of the continent's interior to the East Coast.

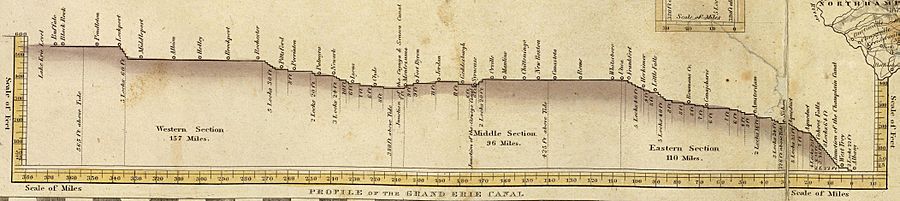

The challenge was that the land rose about 600 feet from the Hudson to Lake Erie. At the time, locks could only raise boats about 12 feet. This meant about fifty locks would be needed along the 360-mile canal. Building such a canal was incredibly expensive. President Thomas Jefferson called it "a little short of madness."

However, Hawley interested New York Governor DeWitt Clinton in the project. Many people opposed it, calling it "Clinton's folly" or "Clinton's ditch." But in 1817, Clinton got approval from the legislature for $7 million to start construction.

The original canal was 363 miles long, connecting Albany on the Hudson to Buffalo on Lake Erie. The channel was cut 40 feet wide and 4 feet deep. The soil removed was piled on one side to create a towpath for animals.

Building the canal through limestone and mountains was a huge task. Advanced engineering from Holland was used. In 1823, construction reached the Niagara Escarpment. Here, five locks were built along a 3-mile stretch to carry the canal over the steep land. Workers used animals to pull "slip scrapers," like early bulldozers, to move earth. The canal's sides and bottom were lined with stone and clay to make it watertight. Hundreds of German masons worked on the stonework. All the work relied on human and animal power, or the force of water. Engineers developed new techniques, like building aqueducts to redirect water. One aqueduct was 950 feet long, spanning 800 feet of river. As the canal was built, the workers and engineers became very skilled.

How the Canal Worked

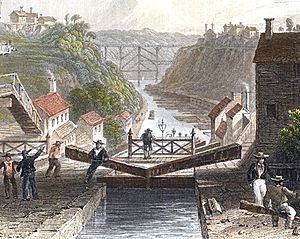

Canal boats, up to 3.5 feet deep, were pulled by horses and mules walking on the towpath. The Erie Canal usually had one towpath on its north side. When two boats met, the boat with the "right of way" stayed on the towpath side. The other boat steered towards the opposite side. Its driver, called a "hoggee," would stop his team. The towline from his horses would go slack, fall into the water, and sink. The first boat's team would step over the sunken towline without stopping. Once clear, the second boat's team would continue.

Even though boats moved slowly, they were very efficient. This smooth, nonstop transportation cut travel time between Albany and Buffalo almost in half, moving day and night. People traveled west on "packet boats" to visit relatives or for relaxing trips. Immigrants often rode on freight boats, sleeping on deck or on crates.

Packet boats, which carried only passengers, could reach speeds of up to five miles per hour. They ran much more often than bumpy stagecoaches. These boats were up to 78 feet long and 14.5 feet wide. They used space cleverly to fit up to 40 passengers at night and three times as many during the day. The best boats had carpeted floors, comfortable chairs, and mahogany tables with newspapers and books. During the day, the cabin was a sitting room. At meal times, crews turned it into a dining room. At night, a curtain divided the cabin into sleeping areas for ladies and gentlemen. Tiered beds folded down from the walls, and extra cots could hang from the ceiling. Some captains even hired musicians for dances. The canal truly brought civilization into the wilderness.

The Lehigh Canal

The Lehigh Canal had a huge impact on the growth of the United States. It was built because two businessmen, Erskine Hazard and Josiah White, needed fuel for their factories. They built the Lehigh Canal and the Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company. They created towns, mines, and transportation systems in a wild area of Eastern Pennsylvania.

The Lehigh Canal was not a true canal in some parts. It was a "navigation" system built along the Lehigh River valley, following the river's path. It was actually two separate projects built 20 years apart, totaling 72 miles along the Lehigh River.

The lower part of the canal (46.5 miles) was built between 1818 and 1820 to transport coal. It connected Mauch Chunk (now Jim Thorpe, PA) to Easton, PA, using special boats that could also travel on the river. This canal carried anthracite coal to cities like Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Trenton, New Jersey, and Wilmington, Delaware. It also helped new industries grow in places like Allentown and Bethlehem. This privately funded canal later became part of the Pennsylvania Canal System. It was sold for recreation in the 1960s.

Pictures

-

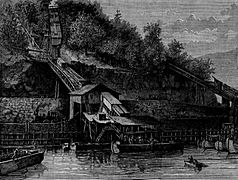

Loading coal at the Mauch Chunk chutes, 1873

-

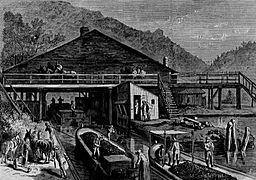

Weigh lock with scales to determine tolls, 1873

-

The canal passing through Bethlehem, 1907

-

Stacked rock detail of lock wall of Lock 28 near White Haven, 2008

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |