Delaware and Hudson Canal facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Delaware and Hudson Canal |

|

|---|---|

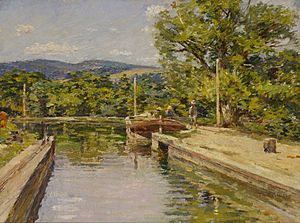

A remaining section of the canal in Sullivan County, NY, used as a linear park

|

|

| Specifications | |

| Length | 108 miles (174 km) |

| Locks | 108 |

| Maximum height above sea level | 1,075 ft (328 m) |

| Status | Closed, partially infilled |

| Navigation authority | |

|

Delaware and Hudson Canal

|

|

| NRHP reference No. | 68000051 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | November 24, 1968 |

| Designated NHL | November 24, 1968 |

| History | |

| Original owner | Delaware and Hudson Canal Company |

| Construction began | 1825 |

| Date of first use | 1828 |

| Date closed | 1902 |

| Geography | |

| Start point | Honesdale, PA |

| End point | Kingston, NY |

The Delaware and Hudson Canal was a very important waterway in the United States. It was built by the Delaware and Hudson Canal Company. This company later became famous for building the Delaware and Hudson Railway.

From 1828 to 1899, the canal was used to transport coal. This coal came from mines in Northeastern Pennsylvania. Barges carried it all the way to the Hudson River. From there, it went to New York City to be sold.

Building the canal was a huge challenge for civil engineering. It even led to new ideas in rail transport. The canal helped New York City grow. It also encouraged people to settle in areas that were not very populated. Unlike many other canals, this one made money for most of its time in use.

Because of its importance, the canal was named a National Historic Landmark in 1968. The canal stopped being used in the early 1900s. Much of it was later drained and filled in. But some parts still exist in New York and Pennsylvania. These parts are now used as parks and historical sites.

Contents

History of the Canal

Before the Canal Was Built

In the early 1800s, a businessman from Philadelphia named William Wurts loved exploring. He spent weeks exploring the wild areas of Northeastern Pennsylvania. He found and mapped black rocks, which were anthracite coal. He thought this coal could be a great source of energy. He brought samples back to Philadelphia to be tested.

William convinced his brothers, Charles and Maurice, to join him. Starting in 1812, they bought land and began mining coal. They could get tons of coal, but it was hard to transport. The rivers were dangerous, and much coal was lost. They realized their coal fields were perfect for supplying New York City. New York City needed energy after the War of 1812.

The Wurts brothers were inspired by the successful Erie Canal. They dreamed of building their own canal. It would go from Pennsylvania to New York. It would follow a route near the Shawangunk Ridge and the Catskill Mountains. This route would lead to the Hudson River near Kingston. This was the path of the Old Mine Road, an old transportation route.

After years of effort by the Wurts brothers, the Delaware and Hudson Canal Company was created. This happened through laws passed in New York and Pennsylvania in 1823. This allowed William and Maurice Wurts to build the canal. The company hired Benjamin Wright, who worked on the Erie Canal. His assistant, John B. Jervis, also helped plan the route. A big challenge was the 600-foot (183 m) height difference. This was between the Delaware River at Lackawaxen and the Hudson at Rondout. The estimated cost was about $1.6 million in 1825.

To get people to invest, the brothers showed off anthracite coal. They did this at a Wall Street coffeehouse in January 1825. People were very excited, and all the company shares were bought quickly.

Building the Canal

Construction began on July 13, 1825. About 2,500 men worked for three years. The canal opened for boats in October 1828. It started at Rondout Creek near Creeklocks. This was close to Kingston, where the creek met the Hudson River.

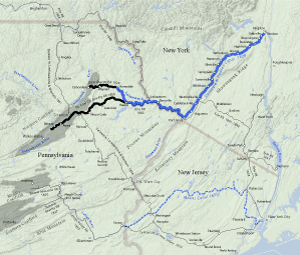

The canal then went southwest along Rondout Creek to Ellenville. It continued through valleys to Port Jervis on the Delaware River. From there, it ran northwest on the New York side of the Delaware. It crossed into Pennsylvania at Lackawaxen. Finally, it followed the Lackawaxen River to Honesdale.

To move coal from the Wurts' mine in the Moosic Mountains to the canal at Honesdale, a special railroad was built. This was the Delaware and Hudson Gravity Railroad. On August 8, 1829, the D&H's first locomotive, the Stourbridge Lion, made history. It was the first locomotive to run on tracks in the United States.

Success and End of Use

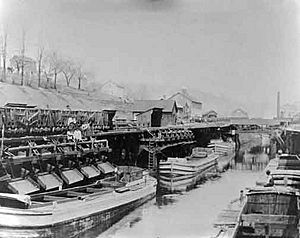

The canal quickly became very busy, just as the Wurtses expected. In 1832, it carried 90,000 tons of coal. It also moved three million board-feet of lumber. The company used its profits to make the canal better. They made it deeper so bigger barges could be used.

In 1850, the Pennsylvania Coal Company built its own gravity railroad. This railroad connected coal fields to the port at Hawley. This brought even more traffic to the canal. However, the two companies later had disagreements. The canal tried to charge higher fees. This led to a court case in 1863. By then, the Erie Railroad had reached Hawley. So, the Pennsylvania Coal Company started using the railroad instead.

The D&H company also started building railroads. Railroads were a new technology that was becoming more popular. They were starting to replace canals. The D&H also made its gravity railroad longer, reaching deeper into the coal fields. By the time Maurice Wurts died in 1854, the company was making good profits.

The Erie Railroad was completed in 1848. Its branch to Hawley opened in 1863. These railroads began the end of the canal's main use. Still, the canal was very successful through the 1870s and 1880s. But by the late 1800s, canals were seen as old-fashioned. Railroads could carry coal more directly and faster. In 1898, the Delaware and Hudson Canal carried its last loads. The next year, the company removed "Canal" from its name. It focused only on its railroad business.

After the Canal Closed

After 1898, the company opened all the gates and drained the canal. A rail owner named Samuel Coykendall bought the canal. He planned to use it for water supply, but this never happened. Instead, he used the northern part of the canal to move cement until 1904. The canal was never used for transport again.

In the early 1900s, the company used some of the canal's land for its growing railroads. Other parts were sold to private companies. Towns along the route also filled in parts of the canal. This was done to expand neighborhoods or for safety. For example, a man supposedly drowned in Port Jervis in 1900.

In the early 2000s, people in Deerpark complained about the canal leaking water. This caused flooding in areas near Cuddebackville. Local officials met to discuss ways to fix this problem.

Protecting the Canal as a Historic Site

The old parts of the canal and its buildings remained. In 1967, the Delaware & Hudson Canal Historical Society was formed. Their museum teaches many students each year. The Neversink Valley Area Museum was started in Orange County, New York, in 1968. The National Park Service recognized the canal site in Orange County as a National Historic Landmark.

In 1969, Sullivan County bought a part of the canal to make a park. Many other buildings and places connected to the canal have been added to historic lists.

How the Canal Worked

The finished canal was 108 miles (174 km) long. It stretched from Honesdale to Kingston. It had 108 locks to help boats move up and down hills. The canal changed elevation by 1,075 feet (328 m). This was more than the Erie Canal's 675 feet (206 m).

The canal channel was four feet (122 cm) deep. It was 32 feet (10 m) wide. Later, it was made deeper to six feet (2 m). There were 137 bridges over the canal. It also had 26 dams and reservoirs. At first, it crossed four rivers using dams. But in the 1840s, John Roebling built aqueducts (water bridges) over the rivers. This made travel faster and safer.

Barges were pulled by mules along a path next to the canal, called a towpath. Mules were used even after steam engines were invented. This was because fast steamboats would create waves that could damage the canal. Children were often hired to lead the mules at first. Later, grown men did this job. They walked 15–20 miles (24–32 km) a day. They also had to pump water out of the barges and care for the animals. They were paid about $3 a month.

The canal was divided into three sections for operations. A trip along the whole canal took about a week. It was closed on Sundays. It also closed every winter when the water froze.

The main purpose of the canal was to carry coal and lumber. There was not much traffic going back to Pennsylvania, mostly empty barges. The company tried offering rides for passengers. Washington Irving, a famous writer, took a trip in the 1840s. But passenger service was not profitable and was stopped.

Canal's Lasting Impact

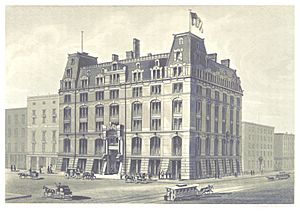

The canal helped New York City grow a lot. Cheap coal from the canal helped the city become more industrial. The canal's first president, Philip Hone, even became New York City's mayor. Later, John Roebling used his experience from the canal to design the Brooklyn Bridge.

In Pennsylvania, the coal regions grew from wild areas. The canal made their coal valuable. This helped the region's economy for a long time.

Many small towns grew along the canal route. Some towns were named after canal leaders. Honesdale was named after Philip Hone. The village of Peenpack became Port Jervis, named after the engineer. Wurtsboro, New York remembers the Wurts brothers. Other New York towns with "port" in their name, like Phillipsport and Port Orange, were also canal towns. Summitville got its name because it was the highest point on the eastern part of the canal.

As cars became popular, they replaced railroads. The canal's path and towpath found new uses as roads. US 6 and PA 590 follow parts of the route in Pennsylvania. US 209 in New York also follows the canal's path. Within towns, streets like Canal Street in Port Jervis and Towpath Road in Ellenville follow the old route.

The canal also led to other inventions. Rosendale cement was found when digging the canal bed near Rosendale. This cement was cheap and helped build the canal. It also created a new industry in the region. Jervis, the engineer, also designed locomotives. One type of locomotive is even named the "Jervis" after him.

The Canal Today

After being named a National Historic Landmark, people became more interested in protecting the canal. Parts of the canal, its structures, and buildings still exist today.

Pennsylvania Sites

- Honesdale: You can find a historical marker here. You can also see parts of the old gravity railroad route. Some canal sections are visible along Routes 6 and 590.

- Lower Lackawaxen Valley: Route 590 follows the canal bed and towpath in some areas. Towpath Road also follows the route in Pike County.

- Lackawaxen and Barryville, New York: Roebling's Delaware Aqueduct is here. It's the only one of the canal's four aqueducts still used today. It's also the oldest wire suspension bridge in the United States. The National Park Service restored it, and cars still drive over it. A former canal company office nearby is now a bed and breakfast.

New York Sites

- Port Jervis: A part of the old towpath is now a city park. Canal Street used to be the canal bed. Fort Decker, the oldest building in the city, housed canal workers.

- Cuddebackville: Orange County has a park along the Neversink River here. You can see the foundations of Roebling's aqueduct. Parts of the canal bed and towpath are in the nearby woods. The Neversink Valley Museum in the park has exhibits about the canal.

- Sullivan County: This county has the largest remaining part of the canal. Some of it still has water. It's called the Delaware and Hudson Canal Linear Park. You can hike, bike, and fish along this 3.5-mile (5.6 km) section. Some locks and structures can be found from different access points along US Route 209.

- Woodridge: Silver Lake Dam was built to provide water for the canal's highest section.

- Ellenville: Towpath Road follows the old canal route. A wet section of the canal bed remains near the village's firehouse.

- Napanoch: A dry section of the canal bed is located near the Eastern Correctional Facility.

- High Falls: Several old locks are here, near where one of Roebling's aqueducts was. The canal museum is also here. The downtown area grew a lot because of the canal.

- Rosendale: The empty canal bed runs next to NY 213.

- Creeklocks: The northernmost lock still exists. The final section before the canal joined the Rondout Creek is also there.

- Kingston: The former port of Rondout was the northern end of the canal. It has been restored and is now a historic waterfront area.

Images for kids