Canal du Midi facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Canal du Midi |

|

|---|---|

The Orb Aqueduct, which allows the Canal du Midi to cross the river Orb in Béziers

|

|

| Specifications | |

| Length | 240 km (150 mi) |

| Maximum boat length | 30 m (98 ft) |

| Maximum boat beam | 5.50 m (18.0 ft) |

| Locks | 65 (originally 86) |

| Maximum height above sea level | 189 m (620 ft) |

| Minimum height above sea level | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Navigation authority | VNF |

| History | |

| Former names | Canal royal en Languedoc |

| Modern name | Canal du Midi |

| Current owner | State of France |

| Original owner | Pierre-Paul Riquet |

| Principal engineer | Pierre-Paul Riquet |

| Other engineer(s) | Marshal Sebastien Vauban, Louis Nicolas de Clerville, François Andréossy |

| Date approved | 1666 |

| Construction began | 1667 |

| Date of first use | 20 May 1681 |

| Date completed | 15 May 1681 |

| Geography | |

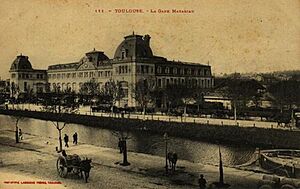

| Start point | Toulouse |

| End point | Marseillan |

| Beginning coordinates | 43°36′40″N 1°25′06″E / 43.61102°N 1.41844°E |

| Ending coordinates | 43°20′24″N 3°32′23″E / 43.34003°N 3.53978°E Les Onglous Lighthouse |

| Branch of | Canal des Deux Mers |

| Connects to | Garonne Lateral Canal, La Nouvelle branch, Canal de Brienne, Hérault, and Étang de Thau |

| Summit: | Seuil de Naurouze |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, iv, vi |

| Inscription | 1996 (20th Session) |

The Canal du Midi is a 240 km (150 mi) long canal in Southern France. It was first called the Canal Royal en Languedoc (Royal Canal in Languedoc). Later, during the French Revolution in 1789, it was renamed the Canal du Midi. This canal is seen as one of the most amazing building projects of the 17th century.

This incredible waterway connects the Garonne River to the Étang de Thau, a large lake on the Mediterranean Sea. Together with the Canal de Garonne, it forms the Canal des Deux Mers. This larger system links the Atlantic Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea.

The "Canal du Midi" specifically refers to the part built from Toulouse to the Mediterranean. The bigger "Deux-Mers" project aimed to connect several waterways. It included the Canal du Midi, the Garonne River (which was partly navigable), the later-built Garonne Lateral Canal, and finally the Gironde estuary near Bordeaux.

King Louis XIV's minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, approved the canal's construction in October 1666. The goal was to help with wheat trade. Pierre-Paul Riquet led the project, and construction lasted from 1666 to 1681. The Canal du Midi is one of Europe's oldest canals still in use today. A big challenge was getting water from the Montagne Noire (Black Mountains) to the highest point of the canal, the Seuil de Naurouze.

Because of its amazing engineering and beautiful design, the Canal du Midi became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1996. It was also named an International Historic Civil Engineering Landmark in 2016.

Contents

Discovering the Canal du Midi

Where is the Canal du Midi located?

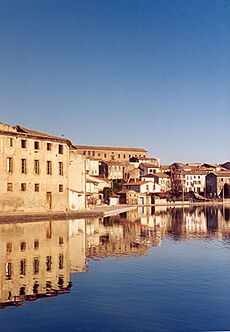

The Canal du Midi is in the south of France. It runs through the areas of Hérault, Aude, and Haute-Garonne. The canal is 240 kilometres (150 mi) long. It starts in the west at Port de l'Embouchure in Toulouse. It ends in the east at Les Onglous in Marseillan. Here, the canal flows into the étang de Thau, a large coastal lake.

How does the canal work?

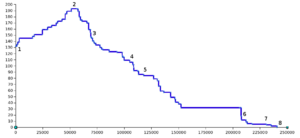

The Canal du Midi is a summit-level canal. This means it climbs to a high point to connect two different valleys. It rises from Toulouse over 52 kilometres (32 mi) to the Seuil de Naurouze. This is the highest point, at an altitude of 189.43 metres (621.5 ft). Water from a special feeder canal enters here. The canal then drops down to the sea over the remaining 188 kilometres (117 mi).

The canal was designed to be two metres (6.6 ft) deep. The minimum depth is 1.80 m (5.9 ft). Boats can have a draft of 1.50 m (4.9 ft). However, boaters sometimes find it shallower due to silt. The canal is usually 20 m (66 ft) wide at the surface. Its width can vary between 16 m (52 ft) and 20 m (66 ft). The bottom of the canal is 10 m (33 ft) wide.

The canal rises from Toulouse to the Seuil de Naurouze. Then it goes down through Castelnaudary, Carcassonne, and Trèbes. It continues to Béziers, passing through the amazing Fonserannes Locks. Finally, it reaches Agde and ends at Sète on the étang de Thau.

The longest section between two locks is 53.87 kilometres (33.47 mi). This is between Argens Lock and the Fonserannes Locks. The shortest section is only 105 m (344 ft) long. It is between the two Fresquel locks.

Who owns and manages the canal?

The French State has owned the Canal du Midi since 1897. Today, Voies Navigables de France (VNF) manages it. VNF is a public group linked to the Ministry of Transport. They are responsible for keeping the canal running smoothly.

The Canal's Amazing History

Early ideas for a canal

Building a canal between the Atlantic and Mediterranean was a very old dream. Many leaders, like Charlemagne and Henry IV, thought about it. It was a big political and economic goal. A canal would save ships from sailing all the way around Spain. This long journey could take a month and was dangerous due due to piracy.

Many plans were suggested in the 16th century. But these projects failed because they couldn't figure out how to supply enough water. The biggest problem was getting water to the highest point of the canal.

Pierre-Paul Riquet's brilliant plan

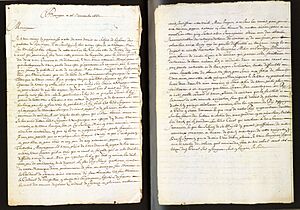

Pierre-Paul Riquet was a wealthy tax collector. He came up with a much better plan than anyone before him. In 1662, King Louis XIV heard Riquet's idea. The King saw it as a way to boost France's economy. He also wanted to create a lasting symbol of his reign.

Riquet found the solution to the water supply problem in 1660. He planned to collect water from the Montagne Noire (Black Mountains). This water would then flow to the Seuil de Naurouze, the canal's highest point. He was inspired by another engineer, Adam de Craponne, who used a similar system.

Riquet planned to build dams and reservoirs to store mountain water. Then, channels would carry this water to the Seuil de Naurouze. The Sor River, near Revel, was a key water source. Other rivers from the Montagne Noire were also part of the plan. The Montagne Noire gets a lot of rain, which was perfect for the canal.

To store the water, Riquet planned three basins. These included the Reservoir of Lampy-Vieux and the large Bassin de Saint-Ferréol. This basin would have a huge earth dam.

In 1664, Riquet built a test channel to prove his idea. This channel diverted water from the Sor to the Seuil de Naurouze. It was called the Rigole de la plaine. This experiment showed that water could reach the canal's highest points. This convinced the King's experts that the canal was possible.

Starting the construction

Even though the project seemed risky, King Louis XIV approved it in October 1666. This was after a committee of experts studied the route. The King's decree gave Riquet the right to build and operate the canal. It also allowed him to build mills and warehouses. Riquet and his family would own the canal and collect tolls. This system ensured the canal would be maintained even if the state had money problems.

The first part of the project, from Toulouse to Trèbes, was estimated to cost 3.6 million livres (old French money). Riquet offered to pay part of the costs himself. The King would pay the rest, using money Riquet collected from the salt tax. The total cost ended up being between 17 and 18 million livres. The King paid 40%, the province paid 40%, and Riquet paid 20%.

Building the canal: A huge effort

Riquet, at 63, began his huge project. He sent his engineers to the Montagne Noire to work on the water supply. This system was a masterpiece of engineering. It successfully fed the canal at its highest point.

Work started on January 1, 1667. The first stone of the Lac de Saint-Ferréol was laid on April 15, 1667. Riquet originally wanted many small reservoirs. But an engineer named Louis Nicolas de Clerville suggested one large reservoir. This was a new idea at the time.

Clerville's military engineers helped build the massive dam for the Bassin de St. Ferréol. This dam was 700 metres (2,300 ft) long and 30 metres (98 ft) high. It was the largest civil engineering project in Europe at the time. A 25 kilometres (16 mi) channel connected it to the Canal du Midi.

In November 1667, a ceremony marked the start of the Garonne lock in Toulouse. Water first filled the section between Seuil de Naurouze and Toulouse in 1671–1672. Boats began using it soon after. By 1673, the section from Naurouze to Trèbes was finished.

The second part of the project connected Trèbes to the Mediterranean Sea. This included building the port of Sète. Riquet faced challenges crossing the Hérault and Libron rivers. He designed special systems of valves and a unique round lock for these crossings. The Agde Round Lock could switch between the canal and the Hérault.

Another challenge was the hill at Ensérune and the descent to Béziers. Riquet solved this by digging the Malpas Tunnel. This was the first canal tunnel ever built. He also built the eight lock chambers at Fonserannes to go down to the Orb River.

Riquet died in October 1680, just before the canal was finished. His sons inherited the canal. The canal was officially opened for navigation on May 15, 1681. After a final inspection, it fully opened to traffic in May 1683.

Who built the canal?

Around 12,000 workers built the canal over 15 years. Riquet hired men and women aged 20 to 50. He organized them into teams. All the work was done by hand, using shovels and pickaxes. Farmers and local workers made up most of the workforce. Riquet also hired soldiers to help.

Riquet paid his workers well and offered good benefits. They got paid for rainy days, Sundays, and holidays. They also received paid sick leave. This was very unusual for the time. Workers earned 20 sols (one livre) per day at first, which was double a farmer's wage.

Women workers were very important. Many came from areas with old Roman water systems. They helped design the channels and perfected the water supply. They also helped build the eight-lock staircase at Fonserannes.

Many different skilled workers were involved. Masons and stonecutters built bridges, locks, and spillways. Blacksmiths kept tools in good repair. Carters, farriers, and sawmill owners also helped. Workers used picks, hoes, and shovels. Gunpowder was used to blast rocks.

Improvements over time

In 1686, Vauban, a royal engineer, inspected the canal. He found it needed repairs. He ordered new work in the Montagne Noire to improve the water supply. This included extending the Rigole de la montagne and strengthening the Bassin de Saint-Ferréol. Riquet had underestimated how much rivers could silt up the canal during floods.

Vauban also built many stone structures to manage river water flowing into the canal. He added spillways to control water levels. He built 49 culverts and aqueducts, like the Cesse Aqueduct and Orbiel Aqueduct. These improvements greatly helped with water supply and management until 1694.

Over the years, more canals were added to connect the Canal du Midi to other places. The Canal de Jonction (junction canal) opened in 1776. It connected to Narbonne. The Canal de Brienne in 1776 allowed boats to bypass a difficult part of the Garonne in Toulouse. In 1857, the Canal Latéral de la Garonne finally completed the link between the Atlantic and Mediterranean. This was Riquet's original dream.

Life on the Canal: Past and Present

How the canal was used for transport

The Canal du Midi was once busy with boats carrying goods and people. Today, it's mostly used by tourists.

In the beginning, small sailing barges used the canal. Men would pull them from the banks. By the mid-1700s, horses took over the towing. Steam tugs appeared in 1834. By 1838, 273 boats regularly used the canal. Passenger and mail boats were also popular until railways arrived in 1857.

A special postal service, called "malle-poste," used boats. Horses pulled these boats along towpaths. This transport was fast, comfortable, and safe. It was a big improvement over roads. The canal could be used all year. A trip from Toulouse to Sète took four days.

By 1855, the journey was cut to 32 hours. This was thanks to faster horses changed every 10 kilometres (6.2 mi). Passengers also switched boats at locks to save time and water. Journeys even happened at night. In 1684, travel from Toulouse to Agde cost one and a half livres. Prices were set by distance, with different rates for different people.

| Year | Number of passengers |

|---|---|

| 1682 | 3,750 (over 6 months) |

| 1740 | 12,500 |

| 1783 | 29,400 |

| 1831 | 71,000 |

| 1854 | 94,000 |

| 1856 | 100,000 |

The canal was mainly used for transporting wheat and wine from Languedoc. This trade made Riquet's family rich. The canal helped producers sell their goods further away. It also brought products like Marseille soap, rice, and spices into Languedoc. However, it mostly served local and national trade, not international routes.

The boats of the canal

When it opened, most boats on the canal carried goods. These barges were about 20 meters long. Horses or men pulled them. Over time, the amount of cargo boats could carry increased. It went from 60 tonnes to 120 tonnes by the early 1800s. In 1778, there were about 250 barges.

By the 1930s, motor barges replaced animal power. This briefly boosted trade. But commercial shipping on the canal ended in the late 1980s. The year 1856 was a record for trade, with over 110 million tonne-kilometres of cargo.

Horses pulled boats for 250 years. A horse can tow up to 120 times its own weight on water. This made animal power very important for the canal.

Mail-barges carried passengers. They started as simple boats with shelters. Later, they became faster and more luxurious, with lounges. The largest could be 30 metres (98 ft) long. Some even had first-class lounges where dinner was served.

Competition from railways

The canal's economic success was limited by other factors. After 200 years, it faced competition from railways and roads. Its busiest time was in the mid-1800s. In 1858, Napoleon III gave control of the canal to the Chemins de fer du Midi railway company for 40 years. This company owned the Bordeaux-Narbonne railway.

This decision hurt canal traffic. The railway company favored its trains. It charged higher prices for canal freight. The Canal du Midi ended up having the highest rates of any French waterway. Railways were also faster and smoother. The canal's limited size for larger boats also became a problem.

| Year | 1854 | 1856 | 1859 | 1879 | 1889 | 1896 | 1900 | 1909 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Millions of tonnes-kilometres | 67 | 110 | 59 | 54 | 32 | 28 | 66 | 80 |

The table shows how rail competition affected the canal. Freight traffic halved between 1856 and 1879. The railway carried much more cargo. In 1898, the State took over the canal again. They removed taxes and tolls, which helped traffic recover to 80 million tonne-kilometres by 1909.

The end of commercial shipping

After World War I, canal traffic was disrupted. It recovered in the 1920s with motor barges. The HPLM company operated 30 boats. World War II caused a slowdown due to oil shortages. But traffic quickly recovered, reaching 110 million km.

However, the canal was too small for newer, larger barges. Railways became even more competitive, and road transport also grew. The Canal du Midi became the third choice for transport. Freight traffic stopped in the 1970s. By 1989, the last two barges stopped running due to a drought. Since 1991, Voies navigables de France has managed the canal.

The Canal du Midi today: Tourism and water supply

Since the late 1900s, the canal offers many activities. It still connects the Atlantic and Mediterranean for boats.

Today, the Canal du Midi is mainly used by tourists. People enjoy boat tours, restaurant-boats, and hotel barges. Tourism grew a lot from the 1960s, especially from Britain. It really took off in the 1980s. The canal is very popular, accounting for one-fifth of all French river tourism. About 80% of visitors are from other countries.

Around 10,000 boats pass through the Fonséranes locks each year. The Argens lock sees even more traffic. The canal supports about 1,900 jobs. Its economic impact is about 122 million euros each year.

The canal is open for navigation from mid-March to early November. The winter months are for maintenance.

The Canal du Midi is also great for sports. People enjoy rowing, canoeing, fishing, cycling, and hiking along its banks. There are paved paths for cycling and roller-skating. Many barges have been turned into homes, theaters, or restaurants.

The canal's role in water supply

During dry seasons, the canal acts as a huge water tank for agriculture. Nearly 700 irrigation pumps are along the canal. This is a key role for the canal today. It can irrigate up to 40,000 hectares (150 sq mi) of farmland.

The Rigole de la plaine brings water from the Sor River for irrigation. The Lac de la Ganguise was built in 1980 near Castelnaudary. It holds 22 million cubic meters of water. In 2005, its capacity was doubled to 44 million cubic meters. This lake can supply the Canal du Midi if other water sources are low.

The canal also provides drinking water. Water treatment plants at Picotalen have supplied drinking water since 1973. They serve nearly 185 towns.

The Canal du Midi as a special heritage site

The Canal du Midi is now seen as an important piece of history and engineering. On December 7, 1996, UNESCO added the canal to its World Heritage Sites list. It was also named a Grand Site of France. This recognition led to a big increase in tourists.

However, maintaining the canal is a challenge. Many groups are involved, and costs are high. Platanus (plane trees) along the banks cause problems. Their roots damage the banks, and their leaves fill the canal. They are also suffering from a disease called canker stain. All 42,000 plane trees will need to be cut down and replaced over the next 15-20 years. New types of trees, like ash and lime, are being planted.

The canal's age makes maintenance expensive. Its operation doesn't generate much money. So, Voies navigables de France (VNF) works with local partners to maintain it. UNESCO's oversight means any changes must protect the canal's historical value.

Amazing Structures of the Canal

The Canal du Midi is 240 km (150 mi) long. It has 328 structures. These include 63 locks, 126 bridges, 55 aqueducts, 7 aqueducts, 6 dams, 1 spillway, and 1 tunnel.

How the canal gets its water

The canal needs 90 million cubic meters of water each year. Riquet created a complex system to supply it. He captured water from the Montagne Noire, many kilometers away. This water was brought to the Seuil de Naurouze, the canal's highest point.

Channels called "Rigole de la montagne" and "Rigole de la plaine" carry this water. They connect three reservoirs (Lampy, Cammazes, and Saint-Ferréol) to the Seuil de Naurouze. The Rigole de la Montagne is 24.269 km (15.080 mi) long. The Rigole de la Plaine is 38.121 km (23.687 mi) long.

The Bassin de Saint-Ferréol is the main water reservoir. It holds 6.3 million cubic meters of water. It was built between 1667 and 1672. The smaller Bassin de Lampy (Lampy-Neuf) was built later, between 1777 and 1782. It holds 1,672,000 cubic meters.

The Bassin de Saint-Ferréol covers 67 hectares (170 acres). It gets water from the Montagne Noire via the Channel of the Mountain. A dam 786 m (2,579 ft) long holds back the water. A museum near the outlets tells the story of the lake's construction.

Riquet also planned a third reservoir at Naurouze. But it was abandoned in 1680 because it filled with silt too quickly.

Other reservoirs were built near Carcassonne to supply the lower canal. In 1957, the Cammazes dam was built on the Sor River. It holds 20 million cubic meters of water. This lake provides drinking water to over 200 towns. Four million cubic meters are reserved for the Canal du Midi.

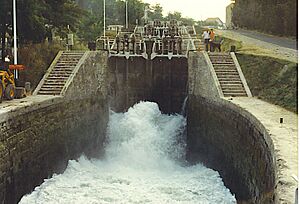

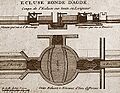

The canal's unique locks

The first locks Riquet built were not strong enough. They collapsed because their straight walls couldn't handle the pressure of the earth. So, he redesigned them with rounded side walls. These "Baroque style" locks were much stronger.

The locks were built of stone and sealed with lime. They had two double-leaf wooden doors. Each door had a valve to drain water.

Riquet's locks were 29.2 m (96 ft) long. They were 5.8 m (19 ft) wide at the doors and 11 m (36 ft) wide in the center. Many locks have been changed over the years.

Near Béziers, there's an amazing staircase of eight locks at Fonsérannes. These locks were carved from solid rock. They had to be different shapes to fit the varying slope. But they all held the same amount of water. This incredible engineering feat was built by two brothers and a workforce mostly of women.

Some locks are true architectural wonders. The Agde Round Lock has three doors. Two connect to the canal, and the third connects to the Hérault River. This protects the canal from river floods. There are also "multiple locks" where several locks are joined together. This saves space and materials on steep slopes.

Today, most locks are electric. This makes opening and closing them much easier than by hand.

Ports along the canal

Many ports were built along the canal. They were used for loading goods and as stops for travelers. Toulouse has two ports: Port de l'Embouchure and Port Saint-Sauveur.

Castelnaudary has a large port called Grand Basin, built between 1666 and 1671. It was a halfway stop between Toulouse and Sète. Carcassonne also has a port, built in 1810. The port of Trèbes is a major stop for boats. Other important ports include Homps and Le Somail.

Near the Mediterranean, there's the port of Agde and the port of Onglous at Marseillan. This is the last port before reaching Sète and the sea. Newer ports like Port-Sud at Ramonville-Saint-Agne and Port-Lauragais also exist.

Aqueducts: Bridges for water

Aqueducts are like bridges that carry the canal over rivers. This prevents rivers from overflowing into the canal and filling it with silt. Some aqueducts date back to Riquet's time. Many more were built later, especially after Vauban's recommendations.

Here are some important aqueducts:

- Orb Aqueduct (PK 208): Opened in 1857, it helps the canal cross the Orb River.

- Cesse Aqueduct (PK 168)

- Répudre Aqueduct (PK 159): Built between 1667 and 1676, it crosses the Répudre River. It was Riquet's first aqueduct.

- Orbiel Aqueduct at Trèbes (PK 117)

- Fresquel Aqueduct (PK 109): Opened in 1810, it allowed the canal to pass through Carcassonne.

- Herbettes Aqueduct (PK 8): A new aqueduct in Toulouse, built in 1983, to cross a motorway.

Other cool structures

- The Malpas Tunnel: This 165 m (541 ft) long tunnel goes through a hill. It was a huge technical challenge for its time.

- The Argent-Double spillway: Located in La Redorte, it has eleven stone arches. It lets excess water flow out of the canal into a stream.

- The Fonserannes water slope: This was built later to bypass the Fonséranes locks. It allowed larger boats to pass more quickly.

- The Ouvrages du Libron: This unique system allows the canal to cross the Libron River near Agde.

- Watermills: Many watermills were built along the canal. They used the water's power to grind grain.

Plants and Animals of the Canal

The Canal du Midi is a long waterway that attracts many animals. Fish like bream live and reproduce in the canal. Other fish use its feeding rivers. Molluscs like freshwater mussels and clams also live here.

Some animals, like Coypu (river rats) and Muskrats, are invasive. They burrow into the banks and damage them. Many animals and birds also come to drink from the canal.

The canal is also home to many plants. Riquet planted trees to stabilize the banks, especially on higher ground. Willow trees were common because they grew fast. Irises were planted to help prevent the banks from sinking.

In the 1700s, trees became a source of income. Mulberry trees were planted for silkworms. Later, poplar trees replaced them for wood. Fruit trees decorated lock-keepers' houses. By the time of the French Revolution, there were about 60,000 trees along the canal. Today, plane trees are the most common.

However, plane trees are now infected with a disease called canker stain. This fungus is spreading quickly. Since 2006, many infected trees have been found. There is no cure, so diseased trees must be cut down. All 42,000 plane trees along the canal will likely need to be replaced. New types of trees, like ash and lime, are being planted instead.

The Canal du Midi as an Inspiration

The Canal du Midi was a huge achievement in the late 1600s. Pierre-Paul Riquet brilliantly managed the water system of the Montagne Noire. King Louis XIV supported it as a symbol of his greatness.

Famous books like the Encyclopedia or Reasoned Dictionary of Science, Arts, and Crafts praised the canal. They compared it to ancient Roman structures. Other writers also celebrated its engineering. The Canal du Midi became a model across Europe.

Thomas Jefferson, who later became a US president, studied the canal in 1787. He was the US Ambassador to France. He imagined building a similar canal in the United States.

In the 1820s, István Széchenyi, a Hungarian reformer, was very impressed by the Canal du Midi. It inspired him to improve navigation on the Danube and Tisza rivers in Hungary.

Key People of the Canal

- Pierre-Paul Riquet: The brilliant designer of the Canal du Midi. He owned and operated the canal with his family. He died in 1680, just before it was finished.

- Jean-Baptiste Colbert: King Louis XIV's finance minister. He helped approve the canal project.

- Sebastien Le Prestre de Vauban: A royal engineer who made many important improvements to the canal between 1685 and 1686.

- François Andreossy: Riquet's close helper. He continued the work after Riquet's death.

- Louis Nicolas de Clerville: An engineer who oversaw the construction and advised Riquet.

Images for kids

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |