William Jessop facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

William Jessop

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 23 January 1745 Devonport, Plymouth, United Kingdom

|

| Died | 8 November 1814 (aged 69) Butterley Hall, Ripley, Derbyshire, United Kingdom

|

| Occupation | Civil Engineer |

| Known for | His Work on Canals, Cromford Canal, West India Docks Oxford Canal, Grand Canal (Ireland), Dublin |

William Jessop (born January 23, 1745 – died November 18, 1814) was a brilliant English civil engineer. He became famous for his amazing work on canals, harbours, and early railways during the late 1700s and early 1800s. He helped connect places and move goods across Britain and Ireland.

Contents

- How William Jessop Started as an Engineer

- Building the Grand Canal of Ireland

- Working with Other Engineers

- The Cromford Canal Project

- Founding the Butterley Company

- Building the Grand Junction Canal

- The West India Docks Project

- Designing the Surrey Iron Railway

- Later Life and Legacy

- William Jessop's Engineering Projects

- See also

How William Jessop Started as an Engineer

William Jessop was born in Devonport, Devon. His father, Josias Jessop, worked as a foreman shipwright (a person who builds and repairs ships) at the Naval Dockyard. Josias was in charge of fixing a wooden lighthouse on the Eddystone Rocks.

In 1755, this lighthouse burned down. A famous engineer named John Smeaton designed a new lighthouse made of stone. Josias Jessop helped oversee its construction. John Smeaton and Josias became good friends. When Josias died in 1761, John Smeaton took William Jessop under his wing. William became Smeaton's student and worked on many canal projects in Yorkshire.

William Jessop worked as Smeaton's helper for several years. Then, he started working as an engineer on his own. He helped Smeaton with important navigation projects like the Calder and Hebble and the Aire and Calder in Yorkshire.

Building the Grand Canal of Ireland

William Jessop's first big project was the Grand Canal of Ireland. This canal project started in 1753. After 17 years, only 14 miles (21 km) of the canal had been built from the Dublin side.

In 1772, a private company was formed to finish the canal. They asked John Smeaton for help, and Smeaton sent Jessop to be the main engineer. Jessop carefully checked the canal's path. He designed a way to carry the canal over the River Liffey using the Leinster Aqueduct. He also managed to build the canal across the huge Bog of Allen, which was a very difficult task. The canal was built on a high embankment over the bog. Jessop also found sources of water and built reservoirs to make sure the canal would always have enough water.

After setting up all the important details, Jessop returned to England. He left a trusted assistant to finish the canal, which was completed in 1805. Jessop was involved with the Irish canal until about 1787, when other projects began to take up his time.

Working with Other Engineers

Jessop was a very humble person. He didn't try to make himself seem more important than others. Unlike some engineers, he wasn't jealous of younger engineers who were becoming successful. Instead, he encouraged them. If he was too busy for a project, he would often suggest another engineer.

For example, he recommended John Rennie the Elder for the job of engineer for the Lancaster Canal Company. This helped Rennie become well-known. In 1793, when Jessop was a consulting engineer for the Ellesmere Canal Company, they hired a less experienced engineer named Thomas Telford. Telford had never designed canals before, but with Jessop's advice and help, Telford made the project a success. Jessop supported Telford, even when the company thought Telford's designs for aqueducts were too ambitious.

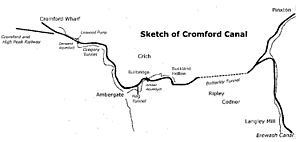

The Cromford Canal Project

In 1789, Jessop became the chief engineer for the Cromford Canal Company. This canal was planned to move limestone, coal, and iron ore from the Derwent and Erewash valleys. It would connect to the nearby Erewash Canal.

Two important parts of this canal were the Derwent Viaduct and the Butterley Tunnel. The Derwent Viaduct was a single-span bridge that carried the canal over the River Derwent, Derbyshire. In 1793, part of this viaduct collapsed. Jessop took the blame, saying he hadn't made the front walls strong enough. He paid for the repairs and strengthening himself.

The Butterley Tunnel was very long, about 2,712 meters (2,966 yards). It was 2.7 meters (9 feet) wide and 2.4 meters (8 feet) high. To build it, workers had to dig 33 shafts from the surface down to the tunnel. Jessop also built the Butterley Reservoir above the tunnel, covering about 20 hectares (50 acres).

Founding the Butterley Company

In 1790, Jessop started the Butterley Iron Works in Derbyshire. He partnered with Benjamin Outram, Francis Beresford, and John Wright. This company made cast-iron rails, which Jessop had used for a horse-drawn railway in Leicestershire in 1789. Outram focused on making the iron parts and equipment needed for Jessop's engineering projects.

Building the Grand Junction Canal

The Oxford Canal had been built by James Brindley and helped transport coal to many parts of southern England. However, it wasn't a direct enough route between the Midlands and London. So, a new canal was proposed. It would run from the Oxford Canal at Braunston, near Rugby, Warwickshire, all the way to the Thames at Brentford. This new canal would be 90 miles long.

Jessop was appointed Chief Engineer for this canal in 1793. This canal was especially hard to plan. Other canals usually followed river valleys, only crossing high ground when necessary. But this new canal had to cross rivers like the Ouse and Nene. An aqueduct (a bridge for water) was built at Wolverton, Milton Keynes to carry the canal over the Ouse valley. While the stone aqueduct was being built, temporary locks were used to move boats down one side of the valley and up the other. The original aqueduct failed in 1808 and was replaced by an iron one in 1811. This iron aqueduct, known as the Cosgrove aqueduct, was designed by Benjamin Bevan.

Two tunnels also had to be built: at Braunston and Blisworth. The Blisworth Tunnel caused many problems and wasn't finished when the rest of the canal was ready. Jessop even thought about giving up on it and using locks instead. His temporary solution was a railway line built over the ridge to carry goods until the tunnel was completed. The Grand Junction Canal became incredibly important for trade between London and the Midlands.

The West India Docks Project

The West India Docks were built on the Isle of Dogs in London. They were the first large "wet docks" (enclosed areas of water where ships can load and unload) built in the Port of London. Between 1800 and 1802, a wet dock area of about 1.2 square kilometers (295 acres) was created. It was 7.3 meters (24 feet) deep and could hold 600 ships. Jessop was the Chief Engineer for these docks, with Ralph Walker as his assistant.

Designing the Surrey Iron Railway

In 1799, there were two different ideas for transportation from London to Portsmouth. One was for a canal, and the other was for a tramway (a railway for horse-drawn carriages). The first part of the proposed Surrey Iron Railway was to go from Wandsworth to Croydon. Jessop was asked for his opinion on which idea was better.

He said the tramway was a better plan because a canal would need too much water and would reduce the water supply in the River Wandle. So, it was decided to build a tramway from Wandsworth to Croydon, along with a basin (a dock) at Wandsworth. Jessop was appointed Chief Engineer for this project in 1801. In 1802, the Wandsworth Basin and the railway line were finished. This railway was eventually replaced by steam locomotives.

Later Life and Legacy

From 1784 to 1805, Jessop lived in Newark in Nottinghamshire. He even served as the town mayor twice.

In his later years, Jessop became increasingly affected by a type of paralysis. By 1805, his active career as an engineer came to an end. He passed away at his home, Butterley Hall, on November 18, 1814. A year after his death, the Jessop Memorial was built east of Ripley in Codnor Park. This 21-meter (70-foot) Doric column can no longer be climbed because it is unsafe. His son, Josias Jessop, also became a successful engineer.

William Jessop was unique because he connected the era of canal engineers with the railway engineers who came later. He didn't become as famous as he deserved because he was so modest. Some of his works were even wrongly credited to engineers who were his assistants. Unlike some engineers, Jessop never argued with his fellow professionals. He was highly respected by almost everyone who worked with him or for him.

William Jessop's Engineering Projects

- The Aire and Calder Navigation

- The Calder and Hebble Navigation (1758–1770)

- The Caledonian Canal

- The Ripon Canal (1767)

- The Chester Canal (May 1778)

- The Leicester Navigation (1791-1794)

- The Barnsley Canal (1792–1802)

- The Grand Canal of Ireland between the River Shannon and Dublin (1773–1805)

- The Grand Junction Canal (1793–1805), which later became part of the Grand Union Canal

- The Cromford Canal, Derbyshire/Nottinghamshire

- The Nottingham Canal (1792–1796)

- The River Trent Navigation

- The Grantham Canal (1793–1797), the first English canal that relied completely on reservoirs for its water supply

- Engineer for the Ellesmere Canal (1793–1805), with detailed design by Thomas Telford

- The Rochdale Canal (1794–1798)

- The Sleaford Navigation (1794)

- The West India Docks and Isle of Dogs canal, London (1800–1802)

- The Surrey Iron Railway, connecting Wandsworth and Croydon (1801–1802), considered by some to be the world's first public railway (though horse-drawn)

- The 'Floating Harbour' in Bristol (1804–1809)

- The Kilmarnock and Troon Railway (1807–1812; the first railway in Scotland approved by Act of Parliament)

- Harbours at Shoreham-by-Sea and Littlehampton, West Sussex

|

See also