Canals of the United Kingdom facts for kids

The canals of the United Kingdom are a big part of the country's waterways. They have a long and interesting history, from being used for watering farms (called irrigation) and moving goods, to becoming super important during the Industrial Revolution, and now, they're mostly used for fun activities like recreational boating. Even though many canals were left unused for a while, today the canal system in the UK is becoming popular again. Old, unused canals are being reopened, and some new ones are even being built! In England and Wales, canals are looked after by special groups called navigation authorities. The biggest ones are the Canal & River Trust and the Environment Agency, but other canals are run by companies, local councils, or charities.

Most canals in the United Kingdom can fit boats between 55 and 72 feet (about 17 to 22 meters) long. These days, they are mainly used for holidays and leisure. Some canals are much bigger, like the New Junction Canal and the Gloucester and Sharpness Canal, which can take boats up to 230 feet (70 meters) long. The Manchester Ship Canal is a special one built just for ships. When it opened in 1894, it was the biggest ship canal in the world! It allowed ships up to 600 feet (183 meters) long to travel its 36-mile (58 km) route.

Contents

Canals Through Time: A Brief History

Canals were first used in Britain when the Romans were there, mainly to help water farms. The Romans also built some canals that boats could use, like the Foss Dyke, to connect rivers. This made it easier to transport things inland by water.

Britain's network of waterways grew as factories and businesses needed to move more goods. Canals were super important during the Industrial Revolution because roads at the time were not good enough for lots of heavy traffic. It was hard to move large amounts of materials, especially delicate items like pottery, quickly by road. Canal boats were much faster, could carry huge amounts of goods, and were safer for fragile items. After the success of the Sankey Canal and then the Bridgewater Canal, many more canals were built. They connected industrial areas, cities, and ports, moving raw materials (like coal and wood) and finished products. This helped ordinary people too! In Manchester, the price of coal dropped by 75% when the Bridgewater Canal opened.

As the Industrial Revolution continued in the late 1700s and early 1800s, new technology helped improve canals. Early canals curved around hills and valleys, but later ones were built straighter. Locks helped boats go up and down hills. Canals also crossed valleys on tall aqueducts and went through hills in long tunnels.

From the mid-1800s, railways started to take over from canals, especially the narrow ones (about 7 feet or 2.1 meters wide) that couldn't fit bigger boats. As trains and later road vehicles got better, they became cheaper and faster than the narrow canal system, and could carry much more cargo. The canal network began to shrink, and many canals were even bought by railway companies. Some narrow canals became unusable, filled with weeds, mud, and rubbish.

There was a final burst of building wider waterways, like the Caledonian Canal and the Manchester Ship Canal. The last new canal built before the year 2000 was the New Junction Canal in Yorkshire in 1905. As competition grew, single horse-drawn narrowboats were replaced by boats powered by steam and later diesel engines. Many boat families even started living on their boats full-time to save money and help with the boat work. This is how the famous "boatman's cabin" came about, known for its bright white lace, shiny brass, and brightly painted metal.

Even though tolls (fees to use the canals) kept getting lower, moving heavy, non-perishable goods by water was still possible on some waterways. But the end for commercial carrying on narrow canals came in the winter of 1962–63. A very long, hard frost froze the canals for three months! Some customers switched to road and rail transport to make sure their goods arrived, and they never came back to canals. Other narrowboat traffic slowly stopped as people switched from coal to oil, factories next to canals closed, and heavy industries in Britain declined. The very last long-distance narrowboat journeys, carrying coal, stopped in 1970. However, some regular trips continued, like lime juice until 1981, and aggregates (like sand and gravel) on the River Soar until 1988.

Some larger waterways, especially the Manchester Ship Canal and the Aire & Calder Navigation, are still used today, moving millions of tonnes of goods each year. There are still hopes for more development, but the way goods are moved in large containers (called containerisation) has mostly bypassed the waterways.

Canals for Fun! (Leisure Use)

In the second half of the 1900s, as canals were used less for moving goods, people started to become interested in their history and how they could be used for fun. A lot of credit for this goes to L. T. C. Rolt, who wrote a book called Narrow Boat in 1944. It was about a journey he took on a narrowboat named Cressy. A very important step was the creation of the Inland Waterways Association. Also, new companies started renting out boats for holidays, following the example of similar companies on the Norfolk Broads, which had been popular for leisure boating for a long time. The group in charge of canals, the British Waterways Board, even started renting out their own holiday boats from the late 1950s.

Holidaymakers began renting 'narrowboats' and exploring the canals, visiting towns and villages along the way. Other people bought boats to use for weekend trips and longer holidays. Canal holidays became even more well-known when big travel agencies started including canal boatyards in their brochures. Canal holidays became popular because they were relaxing, affordable (you could cook your own food), and offered a variety of scenery, from busy London to the Scottish Highlands. This growing interest came just in time! It gave local canal groups the power they needed to fight against government plans in the 1960s to close canals that weren't making money. They also fought against local councils and newspapers that wanted to "fill in this eyesore" or "close the killer canal" (when someone accidentally fell in). Soon, enthusiastic volunteers were repairing canals that were officially open but couldn't be used, and then they moved on to restoring canals that were officially closed. They showed everyone that these canals could be used again.

Local councils started to see how clean, well-used waterways brought visitors to other towns and pubs along the water – not just boaters, but also people who just liked being near water and watching boats (these people are sometimes called gongoozlers). They began to clean up their own watersides and push for "their" canal to be restored. Because of this growing interest, for the first time in a hundred years, some new canal routes have been built (like the Ribble Link and the Liverpool Canal Link). Another one is currently being built (the Fens Waterways Link). Big projects, like fixing the Anderton Boat Lift or building the Falkirk Wheel, received money from the European Union and the Millennium Fund. The Rochdale Canal, the Huddersfield Narrow Canal, and the Droitwich Canals have all been restored and reopened for boats since the year 2000.

Canals Today

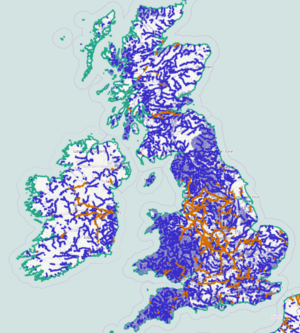

Today, there are about 4,700 miles (7,564 km) of canals and rivers in the United Kingdom that boats can use. About 2,700 miles (4,345 km) of these are connected into one big system in England and Wales. This network stretches from Bristol to London, Liverpool to Goole, and Lancaster to Ripon. It connects the Irish Sea, the North Sea, and the mouths of the Humber, Thames, Mersey, Severn, and Ribble rivers. This whole network can be navigated by a narrowboat (a boat about 7 feet or 2.1 meters wide) that is no longer than about 56 feet (17 meters). There are also some routes that are not connected to the main network, especially in Scotland. For example, you can travel from Glasgow to Edinburgh using the Forth and Clyde Canal, the Falkirk Wheel, and the Union Canal. Another route goes from Fort William to Inverness via the Caledonian Canal (which includes Loch Lochy, Loch Oich, and Loch Ness).

There are four separate parts of the canal network that can be used by wider boats, around 12.6 feet (3.8 meters) wide. However, there are plans and ongoing projects to connect these sections, which would allow wide boats to travel freely between them and create a true north-south and east-west network.

Groups like the Inland Waterways Association work to protect the canals we have now and help restore old waterways that could once be used by boats. In 2005, British Waterways (which is now the Canal & River Trust) hoped to carry four times more cargo on Britain's canals, aiming for six million tonnes by 2010. This would involve moving large amounts of waste to disposal sites.

The speed limit for most canals in the United Kingdom run by the Canal & River Trust is 4 mph (6.4 km/h). This speed is measured over the ground, not just through the water.

Cool Canal Features

Aqueducts

Canal aqueducts are like bridges that carry a canal over a valley, road, railway, or even another canal. The Dundas Aqueduct is made of stone in a classic style. The Pontcysyllte Aqueduct is an iron trough on tall stone pillars. The Barton Swing Aqueduct can swing open to let ships pass underneath on the Manchester Ship Canal. Three Bridges, London is a clever design where the Grand Junction Canal, a road, and a railway line all cross each other.

Boat Lifts

Boat lifts are amazing machines that lift boats from one water level to another.

Inclined Planes

Inclined planes are ramps that move boats up or down hills, often on special cradles.

Locks

Locks are the most common way to raise or lower a boat from one water level to another. A lock is a special chamber where the water level can be changed.

When there's a big height difference, locks are built close together in a series called a flight, like at Caen Hill Locks. If the hill is very steep, a set of staircase locks might be used, where one lock leads directly into the next, like the Bingley Five Rise Locks. At the other extreme, stop locks have little or no change in water level. They were built to save water where one canal joined another. An interesting example is King's Norton Stop Lock, which has special guillotine gates.

Different Kinds of Canal Boats

- Broad-beam boats (also called "wide boats" on the Grand Union canal, about 7 to 14 feet or 2.2 to 4.3 meters wide)

- Cabin Cruisers (often used for holidays)

- Keels (used on the Aire and Calder Navigation)

- Narrowboats (about 6 feet 10 inches or 2.08 meters wide); originally working boats, now mostly used for fun)

- Short boats (used on Northern canals like the Leeds & Liverpool and Calder & Hebble)

- Sloops (used on the Aire and Calder Navigation)

- Tom Pudding coal tubs (special boats used to carry coal on the Aire and Calder Navigation)

- Tub boats (smaller boats used on canals like the Bude Canal and the Grand Western Canal)

- Widebeams (canalboats wider than 14 feet or 4.3 meters)

Where to Learn More: Canal Museums

- National Waterways Museum, Ellesmere Port, Merseyside

- Foxton Canal Museum, Harborough, Leicestershire

- Galton Valley Canal Heritage Centre, Smethwick, West Midlands

- Gloucester Waterways Museum

- Kennet & Avon Canal Museum, Devizes, Wiltshire

- Linlithgow Canal Centre, Scotland

- Llangollen Canal Museum, North Wales

- London Canal Museum, Kings Cross, London

- Portland Basin Museum, Manchester

- Stoke Bruerne Canal Museum, Northamptonshire

- Tapton Lock Visitor Centre, Chesterfield

- Yorkshire Waterways Museum, Goole, East Yorkshire

Images for kids

-

The Oxford Canal near Rugby

-

The Kennet and Avon Canal near the Dundas Aqueduct, Wiltshire

-

Bridge over Birmingham Canal Old Main Line in downtown Birmingham

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |