Grand Western Canal facts for kids

The Grand Western Canal is a historic waterway in the United Kingdom. It was built to connect Taunton in Somerset with Tiverton in Devon. The main idea was to create a water link between the Bristol Channel and the English Channel. This would let ships avoid the dangerous journey around Land's End. The canal also helped transport important materials like limestone and coal to places that made lime kilns. The lime was then used as fertiliser and for building.

The canal was built in two main parts. The first part, from Tiverton to Lowdwells (on the Devon/Somerset border), opened in 1814. This section was wide enough for large barges that could carry up to 40 tons of goods. The second part, in Somerset, opened later in 1839. It was designed for smaller boats called tub boats, which were about 20 feet (6 meters) long and carried about eight tons. This part was special because it included an inclined plane and seven boat lifts. These were the first boat lifts used for business in the UK, built almost 40 years before the famous Anderton Boat Lift.

Today, the 11-mile (18 km) section in Devon is still open. It is now a special country park and a local nature reserve, where people can enjoy boating and nature. The Somerset section of the canal closed in 1867. Over time, much of it has disappeared, but parts are now used as footpaths. It remains an interesting historical site, and archaeologists have studied some areas.

Contents

Canal History: Connecting Two Coasts

The Grand Western Canal was one of many ideas to make sea travel safer and faster. Ships often faced dangers and delays sailing around Land's End to get between the Bristol Channel and the English Channel. Before this canal, some rivers were already made easier to navigate. For example, a canal from the River Exe to Exeter opened in 1566. Also, parts of the River Tone were made navigable to Taunton by 1717.

In 1768, a group asked James Brindley to survey a canal route between Taunton and Exeter. Later, in 1794, another group, the Grand Western Canal Committee, asked John Rennie to survey a different route. His plan was chosen. Even though the City of Exeter worried about competition, an Act of Parliament was passed on March 24, 1796. This law allowed the canal to be built.

The Act said the canal would go from Taunton to Topsham, with branches to Tiverton and Cullompton. The company could raise £220,000 (and more if needed) to build it. They could also improve the River Tone near Taunton. However, construction didn't start right away.

Building the Canal: Phase One

Work finally began in 1810, led by John Thomas. Surprisingly, they decided to start building in the middle of the planned route. They began with a 2.5-mile (4 km) section of the main line and the 9-mile (14 km) branch to Tiverton. The idea was that there was a lot of limestone to transport from quarries at Canonsleigh to Tiverton. This trade would bring in money quickly.

They also decided to dig the highest part of the canal 16 feet (5 meters) lower than first planned. This meant no locks would be needed there, but it required a lot more digging. Another Act of Parliament was passed in 1811 to approve these changes. It also allowed the canal to be rerouted near Halberton, where Rock Bridge was built to carry a road over the canal. Other bridges were also built in Halberton for smaller roads.

Costs were much higher than expected, so work stopped in June 1811. After many discussions, they decided to continue. By 1812, progress was being made, but it was hard work because of the rock cuttings at Holcombe Rogus. The canal also leaked in some places, so they had to line sections with special clay. Lime kilns were built to provide materials. These old kilns can still be seen next to the canal near Waytown Tunnel.

The first part of the canal cost £244,505. It officially opened on August 25, 1814. The very first boat traveled from Lowdwells to Tiverton, carrying coal. In Sampford Peverell, two new rectories were built in 1836 by the canal company. This was to make up for cutting through the old rectory's land and knocking down part of it. Two road bridges were also needed in the village.

Building the Canal: Phase Two

After the first section opened, not as many boats used it as hoped. This made it difficult to raise money to build the rest of the canal. However, in 1829, James Green became interested in connecting the canal to Taunton. He had worked on the Bude Canal, which used inclined planes for changing levels. He suggested a similar idea for the Grand Western Canal. The Bridgwater and Taunton Canal had opened in 1827, making it easier to travel from Taunton to Bridgwater.

In 1830, Green suggested using vertical boat lifts instead of inclined planes. He estimated the cost would be £65,000. Work began in 1831 and moved quickly. They built a bridge at Bradford on Tone and Harpford Bridge at Langford Budville, where a new warehouse was also constructed. In Nynehead, two aqueducts were needed in addition to a boat lift.

The original plan from 1796 was for the canal to join the River Tone at Taunton. But by 1830, there were disagreements between the River Tone managers and the new Bridgwater and Taunton Canal company. The Grand Western Canal company decided it would be better to connect directly to the Bridgwater and Taunton Canal. An Act of Parliament in 1832 made the Bridgwater and Taunton Canal build a link between the Tone and the Grand Western Canal. This link was built in 1834.

The plans for the main canal line included seven lifts and one inclined plane. These new features caused delays in finishing the canal. There were problems with the design of the lifts, and even though Green paid to fix them, the canal couldn't open. The inclined plane also had issues. The canal partly opened to Wellington in 1835, but James Green was dismissed in January 1836.

Finishing the Project

Engineer W. A. Provis was asked to check the work and report on the lifts and the inclined plane's failures. His report gave important information about the canal's construction. Some repairs were made, including adding a steam engine to power the Wellisford incline. The 14-mile (23 km) extension fully opened on June 28, 1838, costing about £80,000.

How Boat Lifts Worked

James Green's use of boat lifts was very new for the time. The basic idea had been suggested before, but no one had made them work well for commercial use. Other attempts at boat lifts on canals like the Somerset Coal Canal and the Ellesmere Canal had failed or were replaced by locks.

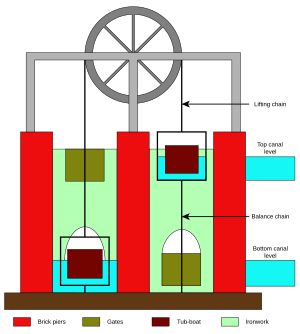

Simple Principles

Green built seven boat lifts without any successful examples to copy. The idea was simple: two large boxes, called caissons, were hung from three big wheels. The caisson at the bottom was pushed against the front wall of the lift to create a seal. Then, a door opened to let a boat float in. The caisson at the top was sealed against the back wall in the same way.

When both boats were inside their caissons, the doors closed, and the seals were released. Because a boat floats by pushing away its own weight in water, the system should be balanced. Only a small amount of energy was needed to start the boats moving. As one caisson went down, the other went up. When the top caisson reached the bottom, the seals were applied, the doors opened, and the boats could continue their journey.

To keep the balance, a second chain was attached to the bottom of each caisson. This made sure the total length of chain on each side of the lift stayed the same. As a caisson went down, the chain coiled up at the bottom. The small amount of energy needed to move the boats came from making sure the caisson going up had a little less water in it than the one going down. This meant the descending caisson was slightly heavier, providing the power. About 2 inches (5 cm) of water, weighing about a ton, was enough.

Solving the Problems

The main problem was that the water in the caisson chambers was supposed to be lower than the canal water. This wasn't done correctly. So, the lower caisson didn't sink deep enough for boats to float out easily. Attempts to add gates and drain the water didn't work well. In the end, they built small lock chambers at the bottom of each lift. These chambers would fill with water from the upper level, allowing the boat to float out. Then, the boat would drop the last 3 feet (1 meter) like in a normal lock. Only the lift at Greenham used the original idea of draining the water to lower the level in the chambers.

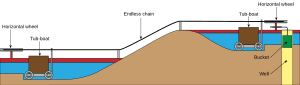

The inclined plane had problems because of a mistake in calculations. Its power came from a large tank filled with water. This tank would go down a shaft, pulling one boat on a trolley up the slope while another boat went down. When the tank reached the bottom, the water would empty, and a second tank would be used to reverse the process. James Green had used this design successfully on the Bude Canal. However, the tanks at Wellisford were too small. On the Bude Canal, a 15-ton water tank was needed to lift a 6-ton boat. The Grand Western Canal used 8-ton boats, but its tanks only held 10 tons of water. Tests showed about 25 tons were needed. This is why a steam engine was brought in to provide the power.

Where the Boat Lifts Were

- Greenham Lift: 42 ft (12.8 m)

- Wellisford Plane: 81 ft (24.7 m) rise, 440 ft (134 m) long

- Winsbeer Lift: 18 ft (5.5 m)

- Nynehead Lift: 24 ft (7.3 m)

- Trefusis Lift: 38.5 ft (11.7 m)

- Allerford Lift: 19 ft (5.8 m)

- Norton Fitzwarren Lift: 12.5 ft (3.8 m)

- Taunton Lift: 23.5 ft (7.2 m)

Canal Operation and Decline

The Somerset part of the canal was for tub-boats, which were about 20 feet (6 meters) long and carried eight tons. The Devon part was for larger barges, carrying up to 40 tons. The money earned from tolls steadily grew from £971 in 1835 to £4,926 in 1844.

But then, competition from railways began. The Bristol and Exeter Railway reached Taunton in 1842 and Exeter in 1844. A branch line to Tiverton opened in 1848. Even though the canal company received £1,200 for lost business when an aqueduct was built over the railway, the canal's income started to drop almost immediately.

By 1853, the canal's income was no longer enough to cover its running costs. So, the canal was leased to the Bristol and Exeter Railway. Ten years later, a new Act of Parliament allowed the canal to be sold to the railway company. The Somerset section of the canal was closed in 1867. The lifts were taken apart, and most of the land was sold back to its original owners.

The Canal's Slow Disappearance

Limestone continued to be transported on the Tiverton section. By 1904, only two boats were working on the canal. The last commercial transport was roadstone from Whipcott quarry to Tiverton, which continued until 1925. After that, the only money came from washing sheep (a charge was made for every 20 sheep) and selling water lilies that grew in the canal. In the 1930s, dams were built in a section near Halberton because it kept leaking.

The canal became part of the Great Western Railway in 1888. Then, when railways were nationalized in 1948, it became the responsibility of the British Transport Commission. The canal was officially closed in 1962. In 1964, responsibility for it moved to the British Waterways Board.

Bringing the Canal Back to Life

There were plans to use the canal's route for landfill and a bypass. This made local people interested in saving it. The Tiverton Canal Preservation Committee was formed in 1962. This committee became very active when plans came out in 1966 to fill in parts of the canal for housing. Tiverton Borough Council gave the committee permission to talk with the British Waterways Board in March 1967. However, the Board was not willing to offer money to help.

New laws helped the cause. From 1968, county councils could create country parks. Also, the Transport Act 1968 allowed the British Waterways Board to let local authorities maintain or buy inland waterways. By 1969, the BWB said they were ready to give the canal to Devon County Council, along with some money for maintenance.

Some council members were unsure, so the preservation committee organized a walk along the entire canal on October 18, 1969. About 400 walkers started, and by the time they reached Tiverton, there were about 1200 people!

The Canal's New Beginning

By April 1970, the British Waterways Board agreed to give the canal to Devon County Council, along with £30,000 for maintenance. The official contract was signed on May 5, 1971. General Sir Hugh Stockwell of the BWB also gave a cheque for £38,750 to Colonel Eric Palmer, chairman of Devon County Council. The canal officially changed hands on June 24, 1971.

The new owners started work right away. The dry section was dug out and lined with a special rubber material to stop leaks. The canal was reopened in 1971. Now, only unpowered boats are allowed, except for a maintenance boat that cuts weeds. The last section from Fossend to Lowdwells is a nature reserve, so no boating or fishing is allowed there.

The canal is now a special country park. A horse-drawn tourist narrowboat takes visitors from Tiverton. Since 2003, powered boats have been allowed on the canal if they have a license from Devon County Council. The canal is also a very popular place for coarse fishing. Fishing rights are leased to the Tiverton and District Angling Club. You need a permit to fish there.

The Somerset section is mostly dry and slowly disappearing due to road improvements and farming. However, a footpath has been made along much of its route. Archaeologists have also dug at the lift in Nynehead, which is the only one with significant remains. This work happened between 1998 and 2003.

Future Plans: Canal Extension

In summer 2017, the Friends of the Grand Western Canal announced a plan to rebuild about 2 miles (3 km) of the canal near Taunton. This would involve building a copy of one of Green's boat lifts near the Silk Mills park and ride car park. A new canal would then be built across public land to join the River Tone. Above the working lift, about 0.5 miles (0.8 km) of the canal would be restored to provide places for boats to moor. Local MPs and Taunton Council support this plan. The Friends hope to study the idea in 2018. A competition was launched to design the new boat lift using modern materials and energy-saving methods, while still looking like Green's original design.

2012 Breach and Repair

In November 2012, very heavy rainfall caused a large break in the Grand Western Canal's banks near Halberton. Nearby homes had to be evacuated. Two temporary dams were put in place. This allowed the rest of the canal to stay open, and the horse-drawn barge at Tiverton could still run in summer 2013. About 400 fish were moved back to the canal from a flooded field, but many fish were lost. About 25 people from the Environment Agency and Tiverton Angling Club helped save the fish. The Environment Agency restocked the canal with 3,000 fish in January 2013, and by May, they were doing well.

Devon County Council agreed to pay for repairs to the canal in time for its 200th anniversary. On July 7, 2013, a £3 million project to fix the breach began. The repairs included rebuilding the broken bank and making it higher to reduce the risk of future flooding. They also improved water management. The canal was lined with a special waterproof material along the bank. A system to monitor water levels and sound an alarm was also installed. This system has sensors in Tiverton and Burlescombe. It alerts canal rangers and Devon County Council if water levels get too high.

Refilling the broken section began on March 4, 2014, using a sluice gate at Rock Bridge. The canal was officially reopened on March 19, 2014. Six narrowboats, led by Councillor Ken Browse, were the first to travel on the newly repaired section.

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |