Somerset Coal Canal facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Somerset Coal Canal |

|

|---|---|

Disused locks at the Combe Hay flight

|

|

Map of the Somerset Coal Canal

|

|

| Specifications | |

| Length | 10.6 miles (17.1 km) (Length of Paulton branch) |

| Maximum boat beam | 7 ft 0 in (2.13 m) |

| Locks | 23 |

| Status | Under restoration |

| History | |

| Former names | Somersetshire Coal Canal |

| Principal engineer | William Jessop William Smith |

| Construction began | 1795 |

| Date of first use | 1798 |

| Date completed | 1805 |

| Date closed | 1898 |

| Date restored | 2012–present |

| Geography | |

| Start point | Paulton / Timsbury |

| End point | Dundas Aqueduct |

| Connects to | Kennet and Avon Canal |

The Somerset Coal Canal was a narrow canal in England, built around 1800. It helped transport coal from the Somerset Coalfield to places like Bath and beyond. At its busiest, this coalfield had 80 different mines!

The canal started in Paulton and Timsbury. It then went through places like Camerton and Dunkerton. It even had a tunnel at Combe Hay. Finally, it joined the Kennet and Avon Canal at Limpley Stoke. This connection allowed coal to travel all the way to London.

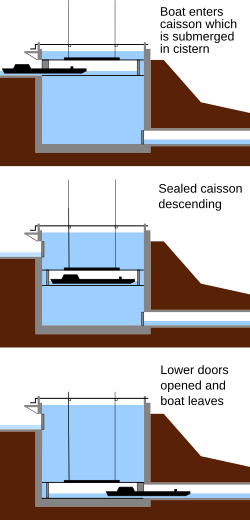

One special part of the canal was at Combe Hay. Engineers tried different ways to move boats up and down the steep hills. They first used special "caisson locks," then an inclined plane, and finally built 22 regular locks.

The part of the canal that went to Radstock was not very successful. It was later replaced by a tramway and then a railway. However, the main part of the canal, from Paulton, was very profitable for almost 100 years. It carried huge amounts of coal, which helped power the nearby city of Bath.

By the 1880s, coal mining in the area started to slow down. Many mines closed because they ran out of coal or got flooded. In 1896, a big pump that kept the canal full of water broke down. Without enough water, only small loads could be carried, which meant less money for the canal company.

The canal stopped being used after 1898 and officially closed in 1902. It was then sold to railway companies. Today, parts of the canal are being restored, with work starting in 2014. The goal is to make the whole canal usable again in the future.

Canal History

Why Was the Canal Built?

In 1763, coal was found in Radstock. Mining began, but moving the coal was hard because the roads were very bad. It was also expensive, and cheaper coal could come from Wales by canal. So, people suggested building a canal to transport coal to Bath and Wiltshire.

In 1793, engineers William Jessop and William Smith surveyed the area. They worked under John Rennie. They estimated the canal would cost about £80,000. William Smith, who also worked at a local coal mine, made important discoveries about rock layers while surveying the canal's path. He noticed how the layers of rock dipped, which helped him develop his famous "stratification theory." Smith was the canal company's surveyor but was later dismissed. However, he was hired again in 1811 to help with repairs.

The plan for the canal was approved by a special law in 1794. More surveys were done by Robert Whitworth and John Sutcliffe, who became the chief engineer.

Building the Canal

Building the canal started in May 1795. The first section, from Paulton to Camerton, was finished on October 1, 1798. The first load of coal was delivered to Bath that day.

Many coal mines in Timsbury and Paulton were connected to the canal by tramways. This meant building bridges over the Cam brook. The path of the Cam brook was also changed in places to protect the canal.

The special caisson lock at Combe Hay was a big challenge. It was designed to save water, but it didn't work well. After several failed attempts, it was replaced. First, they tried an inclined plane, but that also failed. Finally, they built a series of 19 regular locks to move boats up and down the hill.

This new set of locks cost a lot of money. Other canal companies helped pay for it, and a small extra fee was added to the cost of coal. This fee was removed once the costs were paid back.

Here are the prices for using the canal in 1805:

| Cargo | Rate |

|---|---|

| For all Coal, Coke, &c | 2+1⁄2d per Ton, per Mile. |

| For all Iron, Lead, Ores, Cinders, &c | 4d ditto. ditto. |

| For all Stones, Tiles, Bricks, Slate, Timber, &c | 3d ditto. ditto. |

| For all Cattle, Sheep, Swine and other Beasts | 4d ditto. ditto. |

| For all other Goods | 4d ditto. ditto. |

| For every Horse or Ass Travelling on the Railway | 1d each. |

| For every Cow or other Neat Cattle ditto | 1⁄2d ditto. ditto. |

| For Sheep, Swine and Calves ditto | 5d per Score. |

Boats were weighed at Midford, where a special weigh house was built in 1831. Boats would float into a lock, the water would drain, and the boat would rest on a cradle. Weights were then added to measure the cargo. This weigh house was one of only four known in England and Wales.

How the Canal Worked

The canal opened in 1805. It carried coal and even passengers. In 1814, Benedictine monks used the canal to reach Downside Abbey. Limestone from Combe Down was also transported.

The canal was busiest in 1838, carrying over 138,000 tons of cargo. This brought in over £17,000 in fees. The canal remained very busy until the 1870s. At that time, coal production from the mines decreased, and new railways started to compete.

When the main pump at Dunkerton broke, it wasn't replaced. This meant there wasn't enough water to keep the locks working all the time. The canal company went out of business in 1894. The canal closed in 1898 and was officially abandoned in 1904. It was sold to the Great Western Railway for £2,000. The closure caused big problems for the coal mines that relied on the canal for transport.

The Radstock Branch

The Radstock branch of the canal was meant to connect to the main line at Midford. However, it didn't have much traffic. So, instead of many locks, only one lock was built, along with an aqueduct and a short tramway. This led to the branch not being very successful. It was replaced by a tramway in 1815. The tramway used the old canal's towpath.

Canal Engineers

Many engineers and surveyors worked on the Somerset Coal Canal. Some important names include:

- William Bennet

- John Hodgkinson

- Benjamin Outram

- John Rennie

- William Smith

- John Sutcliffe

- Robert Weldon

- Robert Whitworth

Combe Hay and the Caisson Lock

The canal route had a big drop in height, about 135 ft (41 m). This meant it needed a lot of water. The Cam Brook wasn't enough, and local mills also used its water. Each narrow boat carrying 25 tons of coal through the 22 locks would use up 85 tons of water. So, the canal was designed with all 22 locks in one long flight near Combe Hay. A pumping engine was built to lift water from the Cam brook. This was the first canal to rely completely on pumping.

Robert Weldon suggested using "caisson locks" to solve the water problem. Three caisson locks could replace the 22 regular ones and wouldn't waste water. However, this technology was new and had only been tested on a small scale. Each caisson lock was 80 ft (24 m) long and 60 ft (18 m) deep. It had a closed wooden box that could hold a barge. This box moved up and down in a deep pool of water that stayed in the lock. The caisson lock was shown to the Prince Regent, but it had engineering problems and was never successful.

It was temporarily replaced by an inclined plane built by Benjamin Outram. Later, 22 regular locks were built, along with a powerful steam pumping station. This pump could lift 5,000 tons of water in 12 hours.

Building the Caisson Locks

These two pictures show a spillway drain from around 1796. It was found in 2009–2010 at Upper Midford. This was a place where a caisson was planned to move the canal from a higher level to the Midford Aqueduct.

Each caisson would have had a drain like this for maintenance. An old newspaper, the Bath Herald, mentioned these plans in 1798.

Paulton and Timsbury Basins

The Paulton and Timsbury basins were at the end of the northern branch of the canal. They were a central point for at least 15 coal mines around Paulton, Timsbury, and High Littleton. These mines were connected to the canal by tramroads. The Timsbury basin was about 600 ft (180 m) west of the Paulton basin.

On the north side of Timsbury basin, tramroads connected to several coal pits. Some of these lines were still used by horse-drawn wagons in 1873. On the south side of the Paulton basin, tramroads served other collieries and the Paulton Foundry. These lines were no longer used by 1871.

This area is now protected because of its special historical importance.

The Coming of Railways

The first railway to affect the canal was the Bristol and North Somerset Railway. Its line from Frome to Radstock opened in 1854 and took away traffic from the canal's tramway. This tramway finally closed in 1874 when the Somerset and Dorset Railway extended its line to Bath, using the old tramway route from Radstock to Midford. Another railway branch line was built in 1882 from Hallatrow to Camerton, running next to the canal for its last 1+1⁄2 miles (2 km).

The Great Western Railway later built a railway line over some parts of the canal route from Limpley Stoke to Camerton. This line opened in 1910 for passengers and goods. It closed during the First World War, reopened after the war, and finally closed completely in the 1950s. This railway line was even used in the 1950s movie The Titfield Thunderbolt.

The Canal Today

The canal's route goes through mostly farmland and small villages. You can still see several parts of the Paulton and Timsbury basins branch. People are exploring the idea of fully restoring the entire canal from Paulton to Dundas.

At Combe Hay, four of the original locks are now buried. One is under a 20-foot (6 m) railway embankment. Three others were filled with 10 to 20 feet (3–6 m) of building waste after the 1960s. It might not be possible to rebuild these specific locks.

At Upper Midford, the canal is completely blocked by a 40-foot (12 m) high railway embankment. Most of the canal features are on private land. However, parts of the old towpath are still public footpaths. The later railway line between Midford to Wellow has been turned into part of National Cycle Route 24. There's a proposal to put a statue of William Smith, known as the "father of English Geology," next to the path. This would honor his work as the canal's surveyor and his important discoveries about rock layers.

Restoration Work

Limpley Stoke

A 1⁄4-mile (400 m) section at Brassknocker Basin, where the canal meets the Kennet and Avon at Dundas Aqueduct, was restored in the 1980s. It is now a busy marina with boat moorings. When they dug up the old stop lock (where the canals joined), they found it was originally a wide lock (14 feet, 4.3 m) that was later made narrower (7 feet (2.1 m)).

Paulton and Timsbury Basins

Work began in 2013 to uncover and dig out the drydock next to the eastern Paulton Basin. This drydock seems to be the largest on any canal system in England. It's about 30 feet (9.1 m) wide and 83 feet (25 m) long, big enough for three full-length narrowboats to be worked on at once.

The drainage pipe at the drydock's southeast corner was rebuilt in December 2013. The drydock itself was fully dug out in April 2014. The entrance to the drydock had a bridge, which was partly destroyed in 2002 but rebuilt in 2014.

Withy Mills

Digging started in May 2014 at Terminus Bridge. The arch was missing, and the bridge supports were in poor condition. A mound of earth between the supports held back the water from the Paulton and Timsbury Basins. A new earth mound was put in about 25 m (27 yd) west of Terminus Bridge to stop the water, allowing work to continue on the bridge.

During the digging, a drainage pipe was found about 20 m (22 yd) west of Terminus Bridge. Work continued in September and November 2014 to reshape the canal banks. Extra topsoil was removed, and the towpath was rebuilt for about 200 m (220 yd) east of Terminus Bridge. On the same stretch, a retaining wall was found in the south bank, continuing for about 100 m (110 yd). This wall might have been built to repair a weak part of the canal bank. White clay was used to fill in vertical gaps along this wall.

Studying the Canal's History

The canal has been studied for many years. People have explored and worked on restoring parts of it in Wellow and other areas. A lot of effort has gone into trying to find the exact locations of the second and third caisson locks at Combe Hay, but they haven't been found yet.

In October 2006, the Somersetshire Coal Canal Society received a grant of £20,000 from the Heritage Lottery Fund. This money was for a study of one of the locks and other structures at Combe Hay. Many of the locks and related structures are now listed buildings, meaning they are protected because of their historical importance.

Canal Route and Interesting Spots

| Point | Coordinates (Links to map resources) |

OS Grid Ref | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Site of basin | 51°18′14″N 2°29′38″W / 51.304°N 2.494°W | ST655563 | Paulton |

| Site of aqueduct | 51°20′02″N 2°24′32″W / 51.334°N 2.409°W | ST715595 | Dunkerton |

| Site of caisson lock | 51°20′13″N 2°22′59″W / 51.337°N 2.383°W | ST733598 | Combe Hay |

| Junction of branches and tramway connection | 51°20′35″N 2°20′35″W / 51.343°N 2.343°W | ST761605 | Midford |

| Junction with Kennet and Avon Canal | 51°21′40″N 2°18′43″W / 51.361°N 2.312°W | ST783625 | Limpley Stoke |

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |