Somerset Coalfield facts for kids

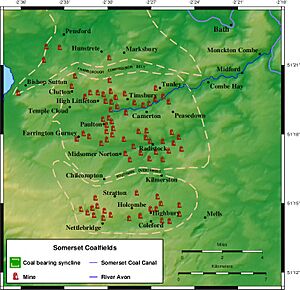

The Somerset Coalfield was an important area in northern Somerset, England, where coal was dug up from the 1400s until 1973. It was part of a bigger coalfield that reached into southern Gloucestershire. The Somerset coalfield stretched from Cromhall in the north to the Mendip Hills in the south. It went from Bath in the east to Nailsea in the west. This whole area was about 240 square miles (620 square kilometres).

Most of the mines were found in the Cam Brook, Wellow Brook, and Nettlebridge Valleys, and also around Radstock and Farrington Gurney. These mines were often grouped together, with several pits in one area owned by the same company. Many mines shared special tracks and tramways to move the coal to the Somerset Coal Canal or to railways for shipping.

The first mines were simple tunnels called adits, where coal was close to the surface. They also used "bell pits," which were shallow holes. These methods changed when miners started digging much deeper. The deepest mine shaft in the area was at the Strap mine in Nettlebridge, which went down 1,838 feet (560 metres)!

Mining had its dangers. Flooding and explosions from coal dust were big problems. This meant mines needed better ways to pump out water and improve air flow. Many mines closed in the 1800s because they ran out of coal. The mines that were still open in 1947 became part of the National Coal Board. But it became too expensive to keep them safe and modern, so the last mine closed in 1973. Even today, you can still see signs of the old mines, like old buildings, piles of waste rock, and parts of the old tramways.

Contents

- What is the Geology of the Coalfield?

- A Brief History of Coal Mining

- Pensford Coal Basin

- Earl of Warwick's Clutton Collieries

- Paulton Basin Mines

- Timsbury and Camerton Mines

- Mines East of Camerton

- Farrington Gurney Mines

- Duchy Mines

- Earl Waldegrave's Radstock Collieries

- Writhlington Collieries

- Norton Hill Collieries

- Nettlebridge Valley Mines

What is the Geology of the Coalfield?

How the Land is Shaped

The Somerset Coalfield covers about 240 square miles (620 square kilometres). It has three main bowl-shaped areas where coal is found, called 'coal basins'. The Pensford basin in the north and the Radstock basin in the south are separated by a fault line called the Farmborough Fault Belt. To the west, there's a smaller basin called Nailsea. The Radstock basin has many faults (cracks in the rock) that made mining tricky.

Layers of Rock and Coal

The coal layers are divided into Lower, Middle, and Upper sections. Coal seams (layers of coal) are found in all of them. The Lower and Middle Coal Measures are deep underground, between 500 and 5,000 feet (150 to 1,500 metres) down. Together, they are about 1,600 feet (490 metres) thick.

Only in the southern part of the Radstock basin and eastern Pensford basin was coal from the Lower and Middle layers mined. The rocks here were squeezed and folded a lot by ancient Earth movements. This caused many cracks and faults in the sandstone and mudstone layers, and in the coal itself. For example, along the Radstock Slide Fault, a coal seam can be broken and shifted by as much as 1,500 feet (460 metres)! This complex geology and thin coal seams made mining difficult and dangerous. Three underground explosions in 1893, 1895, and 1908 were caused by coal dust in the air.

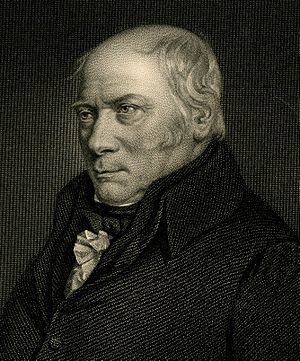

William Smith: The Geology Expert

William Smith, often called the "father of English geology," studied the rocks in this area. He worked at the Mearns Pit at High Littleton. He noticed that rock layers were always in the same order. He also saw that each layer could be identified by the fossils it contained. This idea, called the principle of faunal succession, helped him create the first detailed geological map of England. Smith was a surveyor for the Somerset Coal Canal Company. He mapped the rock layers and their depths, earning him the nickname "Strata Smith."

Types of Coal Seams

Here are some of the coal seams found in the coalfield, listed from the newest (top) to the oldest (bottom). Not all seams are found everywhere, and sometimes it's hard to match them up between different basins.

| Coal measures | Coal seams |

|---|---|

| Upper Coal Measures within the Pennant Sandstones | Forty Yard Coal (Pensford), Withy Mills Coal, Great Coal, Middle Coal, ?Pensford No 2 Coal, Slyving Coal, Bull Coal, Bottom Little Coal, Rock Coal, Farrington Top Coal, Top Coal, ?Streak Coal, Peacock Coal, Middle Coal, No 5 Coal, ?Bromley No 4 Coal, New Coal, No 7 Coal, No 9 Coal, Big Coal, Brights Coal, No 10 Coal (splitting into Nos 8 & 9 Coals), No 11 Coal, Rudge Coal, Temple Cloud Coal, Newbury No 2 Coal, Newbury No 1 Coal, Globe Coal, Warkey Coal |

| Middle Coal Measures | Garden Course Coal, Great Course Coal, Firestone Coal, Little Course Coal, Dungy Drift Coal, Coking Coal |

| Lower Coal Measures | Standing Coal, Main Coal, Perrink Coal, White Axen Coal |

A Brief History of Coal Mining

People believe that coal was mined in this area during Roman times. Records show coal being dug on the Mendips in 1305 and at Kilmersdon in 1437. By the time of Henry VIII, there were coal pits at Clutton, High Littleton, and Stratton-on-the-Fosse.

In the early 1600s, miners mostly dug coal from tunnels called drifts that followed the coal seams. They also dug bell pits. These were vertical shafts, about 4 feet (1.2 metres) wide and up to 60 feet (18 metres) deep, which widened at the bottom. Once all the safe coal was removed, they would dig another pit nearby and fill the old one with waste.

By the early 1800s, about 4,000 people worked in the coalfield. The Somerset Miners' Association was started in 1872. It later became part of the National Union of Mineworkers.

Coal was used for many things. It heated limekilns to make lime for building mortar and to improve farm soil. From 1820, coal was used to make gas for lighting and to power steam engines in wool factories. Coke, made from coal, was used to dry malt for making beer.

How Coal Was Transported

The coalfield didn't have many people living nearby, and there wasn't a big industry that needed coal right there. So, getting the coal to market was a huge challenge. Before good roads were built, the local roads were terrible. People often complained that the roads were "very founderous" (muddy and broken) because of all the coal carts.

In the 1700s, better roads called turnpikes started to appear in Somerset. These made it much easier to move coal. One horse could now pull four times more coal with a light cart than it could carry on its back before!

But roads weren't enough. People realized that canals were the best way to move large amounts of coal. In 1794, coal owners decided to build the Somerset Coal Canal. It had two branches that connected to the Kennet and Avon Canal near Bath. Later, coal was also moved by the Bristol and North Somerset Railway and the Somerset and Dorset Joint Railway. These railways were connected to the mines by smaller tramways. After the first railway opened in 1854, less and less coal was carried by the canal.

The End of Coal Mining

The amount of coal dug up in Somerset grew throughout the 1800s. It reached its highest point around 1901, with 79 different mines producing 1.25 million tons of coal each year. The busiest years were from 1900 to 1920.

However, the industry then started to shrink. The number of mines dropped from 30 at the start of the 1900s to just 12 when the National Coal Board took over all coal mines in 1947. By 1959, only five mines were left, and by 1973, all of them had closed. Even with new investments, like at Norton Hill, the thin coal seams made mining very expensive. Also, a power station switched from coal to oil, and there was less demand for coal overall. This, along with cheaper coal from other areas, led to the closure of the last two mines, Kilmersdon and Writhlington, in September 1973.

The Area Today

Today, most of the old mine sites have been removed or turned into green spaces. The area between the Mendip Hills and the River Avon is now mostly countryside. The towns and villages have some small businesses, but many people live there and travel to work in Bath and Bristol. There are still several limestone quarries in the Mendips.

The Colliers Way (NCR24) is a national cycle path that follows many of the old railway and tramway lines used for coal mining. It runs from Dundas Aqueduct to Frome through Radstock.

The Radstock Museum has interesting exhibits about life in north Somerset since the 1800s. You can learn about the coalfield, its geology, and see items from the Somerset Coal Canal and the old railways.

Pensford Coal Basin

The Pensford coal basin is in the northern part of the coalfield, near places like Bishop Sutton, Pensford, Stanton Drew, Farmborough, and Hunstrete. Some mines were already working here before 1719.

The Old Pit at Bishop Sutton was dug before 1799. It was later bought by William Rees-Mogg (an ancestor of a famous journalist!). This pit went down 304 feet (92.7 metres) but closed by 1855. A "New Pit" was then reopened and dug deeper to reach more coal. It had two shafts, one for lifting coal and one for pumping water. This pit finally closed in 1929.

Pensford Colliery, which opened in 1909, had modern equipment like coal cutters. It had a red-brick building for the winding gear, baths for the miners, and a coal washing plant. But the broken rock layers made mining expensive, and it closed in 1958.

| Pits of the Pensford coal basin | |||||

| Colliery | Location | Opened | Closed | Max shaft depth (ft (m)) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bishop Sutton (old) | Bishop Sutton | c1811 | 1855 | 304 (92.7) | Bought by William Rees-Mogg in 1835 |

| Bishop Sutton (new) | Bishop Sutton | 1855 | 1929 | 877 (267.3) | 1896 owned by F. Spencer, New Rock Colliery, 1908 owned by J Lovell and Sons |

| Bromley | Pensford | 1860 | 1957 | 475 (144.8) | 1896 & 1908 Owned by Bromley Coal Co Ltd. |

| Common Wood Level | Hunstrete | 1829 | 1832 | ? | No coal mined. Attempts made again in 1969 but unsuccessful |

| Farmborough | Farmborough | c1841 | 1847 | 1413 (430.7) | No coal mined |

| Pensford | Pensford | 1909 | 1955 | 1494 (445.4) | |

| Rydon's (or Riding's) | Stanton Drew | 1808 | 1833 | 312 (95) |

Earl of Warwick's Clutton Collieries

The Earl of Warwick owned many businesses, including sawmills, quarries, brickworks, and coal mines around Clutton and High Littleton. The bell pits here were described in 1610 but all closed by 1836. The first deep mine in High Littleton was Mearns Coalworks, which started in 1783. The Greyfield Coal Company began in 1833 and grew after the Bristol and North Somerset Railway opened in 1847. Greyfield Colliery closed in 1911. Maynard Terrace in Clutton was built to house some of the miners.

| Pits of the Earl of Warwick's Clutton Collieries | |||||

| Colliery | Location | Opened | Closed | Max shaft depth (ft (m)) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burchells (sometimes spelt Burchills or Birchill's) | Clutton | 1911 (reopened) | 1921 | 148 (45.1) | |

| Fry's Bottom | Clutton | 1830s | 1885 | 588 (179.2) | |

| Greyfield | Clutton | 1833 | 1911 | 900 (274.3) | 1908 Owned by Greyfield Colliery Co. Ltd., |

| Mooresland | Clutton | 1840s | ? | ? | Output transferred to nearby Greyfield |

Paulton Basin Mines

The mines in the Paulton basin were connected to the northern branch of the Somerset Coal Canal. This canal basin was a hub for tramroads that linked at least 15 mines around Paulton, Timsbury, and High Littleton.

On the north side of the canal, a tramroad served mines like Old Grove, Prior's, Tyning, and Hayeswood. Some parts of this line were still used by horse-drawn wagons in 1873. On the south side, another tramway connected mines like Brittens, Littlebrook, Paulton Ham, Paulton Hill, and Simons Hill. This entire line and the mines it served were no longer used by 1871.

The Paulton area is now a special place because of its history and old buildings.

| Pits of the Paulton Basin | |||||

| Colliery | Location | Opened | Closed | Max shaft depth (ft (m)) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amesbury | High Littleton | before 1701 | early 19th century | 200 (61) | |

| Brewers | Paulton | before 1700 | ? | 102 (31) | |

| Brittens Lower | Paulton | ? | by 1864 | ? | |

| Brittens New | Paulton | ? | by 1864 | ? | |

| Brombel (or Brombells, possibly Allens Paddock) | Paulton | before 1793 | ? | ? | |

| Crossways | Paulton | ? | ? | 144 (43.9) | |

| Goosard (or Gooseward or Goosewardsham or Paulton Lower Engine) | Paulton | 1708 | ? | ? | |

| Hayeswood | Timsbury | 1750 | 1862 | 642 (195.7) | |

| Heighgrove (or Woody Heighgrove) | Paulton | 1753 | 1819 | ? | |

| Littlebrook | Paulton | ? | c1850s | 215 (65.5) | |

| Mearns | High Littleton | 1783 | 1824 | 279 (85) | |

| New Grove (possibly also Priors) | Paulton | 1792 | ? | ? | |

| Tyning | Timsbury | 1766 | ? | ? | Old & New Pits |

| Old Grove | Paulton | ? | ? | 4185 (1373) | |

| Paulton Bottom | Paulton | ? | ? | 60 (18.3) | |

| Paulton Engine | Paulton | before 1750 | ? | 609 (185.6) | Next to Paulton Brass and Iron foundry |

| Paulton Ham | Paulton | c1830s | 1964 | 552 (168.2) | |

| Paulton Hill | Paulton | 1840 | 1864 | 798 (243.2) | |

| Radford | Paulton | c1800 | 1847 | 1152 (351.1) | |

| Salisbury | Paulton | 1792 | 1873 | 150 (45.7) | |

| Simons Hill (also known as Simmons Hill) | Paulton | 1811 | 1844 | 672 (204.8) | |

| Withy Mills | Paulton | ?1804 | 1877 | 804 (245) |

Timsbury and Camerton Mines

The first mine near Timsbury village was called Conygre and opened in 1791. Camerton Old Pit opened in 1781 and went down 921 feet (280.7 metres). It closed around 1898, but its shaft was used for air and as an escape route for the New Pit until 1930. The New Pit was half a mile east and went down 1,818 feet (554.1 metres). It connected underground to Braysdown Colliery in 1928 and closed in 1950.

Today, there are few obvious signs of the old mining activities around Clutton, Temple Cloud, High Littleton, and Timsbury. However, there is a very large "Batch" (a spoil tip) almost in the middle of Camerton. It's now a special Local Nature Reserve. This Batch used to be bare, like the Paulton ones, until the owner's wife paid to have trees planted on it to make the view nicer.

| Pits of the Timsbury and Camerton Collieries | |||||

| Colliery | Location | Opened | Closed | Max shaft depth (ft (m)) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camerton New | Camerton | 1800 | 1950 | 1818 (554.1) (a lesser depth) before 1800 | Site of a massive coal dust explosion at Camerton New in 1893 which killed two miners. |

| Camerton Old | Camerton | 1781 | 1898 | 921 (280.7) | 1896 & 1908 owned by Miss E.E. Jarrett. |

| Lower Congyre | Timsbury | 1847 | 1916 | 1128 (343.8) | Merger of Upper and Lower pits. 1896 owned by Samborne Smith and Company. 1908 Owned by Beaumont, Kennedy and Co |

| Radford | Timsbury | ? | ? | 1152 (351.1) | 1906 Owned by Earl of Waldegrave |

| Upper Congyre | Timsbury | 1791 | 1916 | 1038 (316.4) | Merger of Upper and Lower pits. 1896 owned by Samborne Smith and Company. 1908 Owned by Beaumont, Kennedy and Co. On 6 February 1895 the pit was the site of an explosion which killed seven men. |

Mines East of Camerton

East of Camerton, the coal was buried under newer rock layers, making it harder to mine.

The valleys of the Cam and Wellow Brook still show signs of coal mining from the 1700s to the 1900s. You can often see old mine shafts and spoil heaps, along with remains of the railway and tram lines that connected the mines to the Avon Valley. Parts of the Somersetshire Coal Canal are also important reminders of this mining history.

| Pits to the east of Camerton | |||||

| Colliery | Location | Opened | Closed | Max shaft depth (ft (m)) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bengrove (also called Priston Old and Dunkerton) | between Camerton and Tunley | 1764 | c1774 | 506 (154.2) | |

| Dunkerton | Dunkerton | 1904 | 1925, 1933 | 1651 (503.2) | Poor working conditions led to riots in 1908-9 |

| Hills (also known as Priston or Dunkerton New) | Tunley | 1792 | 1824 | ? | |

| Priston (also known as Tunley) | Tunley | 1914 | 1930 | 750 (228.6) | Last deep mine to be opened in Somerset. |

Farrington Gurney Mines

Mining has been happening around Farrington Gurney since the 1600s. By 1780, the mines were known as Farrington Colliery.

The area still shows signs of its industrial past, like the very noticeable, cone-shaped Old Mills Batch (spoil tip) which doesn't have much plant life on it. The three old mine sites have been redeveloped into light industrial areas, a depot, and a supermarket.

| Pits of Farrington Gurney | |||||

| Colliery | Location | Opened | Closed | Max shaft depth (ft (m)) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Church Field (also known as Farrington of Ruett Slant) | Farrington Gurney | 1921 | 1923 | ? | Drift Mine transferred to Marsh Lane |

| Farrington | Farrington Gurney | 1782 | 1923 | 588 (179.2) | |

| Marsh Lane | Farrington Gurney | 1921 | 1949 | ? | visited by the Prince of Wales on 7 July 1934 |

| Old Mills | Midsomer Norton | 1860 | 1966 | 1098 (334.7) | Merged with Springfield |

| Springfield | Midsomer Norton | 1872 | 1966 | 965 (294.1) | Merged with Old Mills. Owned by W Evans and Co. |

Duchy Mines

The Duchy of Cornwall owned most of the rights to minerals around Midsomer Norton. Several small mines opened around 1750 to dig up these minerals.

| Pits of the Duchy Mines | |||||

| Colliery | Location | Opened | Closed | Max shaft depth (ft (m)) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clandown | Clandown | 1811 | 1929 | 1437 (438) | 1896 owned by Trustees of the late C. Hollwey 1908 Owned by Clandown Colliery Co |

| Old Welton | Midsomer Norton | 1783 | 1896 | 1646 (501.7) | Merged with Clandown. 1896 owned by Old Welton Colliery Co. 1908 Owned by Clandown Colliery Co |

| Welton Hill | Midsomer Norton | 1813 | 1896 | 605 (184.4) |

Earl Waldegrave's Radstock Collieries

In 1763, coal was found in Radstock, and mining began on land owned by the Waldegrave family. In 1896, the mines were owned by the family of the late Countess of Waldegrave.

Radstock was the end point for the southern branch of the Somerset Coal Canal. This canal was later turned into a tramway. Radstock became a center for railway development, with coal depots, coal washing plants, workshops, and a gas works. A railway line from Radstock to Frome was built to carry coal. In the 1870s, this line was updated and connected to the Great Western Railway.

| Pits of Earl Waldegrave's Radstock Collieries | |||||

| Colliery | Location | Opened | Closed | Max shaft depth (ft (m)) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ludlows | Radstock | before 1790 | 1954 | 1686 (531.1) | |

| Middle Pit | Radstock | before 1801 | 1933 | 1791 (545.9) | |

| Old Pit | Radstock | before 1800 | 1858 | 942 (287.1) | |

| Smallcombe | Radstock | 1797 | 1854 | 1074 (327.4) | |

| Tyning | Radstock | 1837 | 1909 | 1007 (306.9) | |

| Wellsway | Westfield | 1829 | 1920 | 754 (229.8) |

Writhlington Collieries

The Writhlington Collieries were east of Radstock and had different owners. In 1896, they were owned by the Writhlington, Huish and Foxcote Colliery Co. The Upper and Lower Writhlington, Huish & Foxcote pits later combined into one large mine.

The land here has different layers of rock, including shales and clays from the Triassic period, and limestone from the Jurassic period. The coal is found underneath these layers. Haydon is a village built to house miners from the local pit. The old railway line and inclined railway at Haydon are important historical features. The landscape still shows signs of the coal industry, and these disturbed areas have become valuable places for wildlife.

The Writhlington spoil heap is a special scientific site because it has many interesting fossils. The Braysdown spoil heap was planted with conifer trees and is now known as Braysdown Hill. The old offices, blacksmith's shop, and stables at the Upper Writhlington Colliery have been turned into homes.

| Pits of the Writhlington Collieries | |||||

| Colliery | Location | Opened | Closed | Max shaft depth (ft (m)) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Braysdown | Peasedown St John | 1845 | 1959 | 1834 (559) | 1896 owned by Danbeny and Scobel 1908 Owned by Braysdown Colliery Co. At nationalisation in 1947 it was producing 37,250 tons. |

| Foxcote | Foxcote | 1853 | 1931 | 1416 (431.6) | 1896 owned by Writhlington, Huish and Foxcote Colliery Co., |

| Huish | Kilmersdon | 1822 | 1912 | 570 (173.7) | 1896 owned by Writhlington, Huish and Foxcote Colliery Co., |

| Kilmersdon | Kilmersdon | 1875 | 1973 | 1582 (482.2) | 1896 & 1908 owned by Kilmersdon Colliery Co. |

| Lower Writhlington | Writhlington | 1829 | 1461 (445.3) | ||

| Shoscombe | Shoscombe | c1828 | by 1860 | 360 (109.7) | |

| Woodborough (also known as Wodborough Old Pit) | east of Radstock | ? | 1840s | 426 (129.8) | |

| Upper Writhligton | Radstock | 1805 | 1972 | 942 (287.1) |

Norton Hill Collieries

The Norton Hill Collieries at Westfield were owned by the Beauchamp family, including Sir Frank Beauchamp. These mines were sometimes called the "Beauchamp goldmines" because they were the most productive in the whole coalfield.

In 1900, a railway was built to connect the colliery to the main Somerset and Dorset Joint Railway.

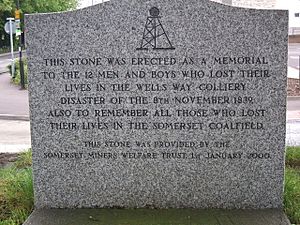

On April 9, 1908, an explosion about 1,500 feet (460 metres) underground killed ten men and boys. At that time, there were no special mine rescue teams, so the manager and volunteers searched for survivors for 10 days. Because of this explosion, Winston Churchill helped pass the Coal Mines Act 1911 to make mines safer.

After the mines became nationalized after World War II, the National Coal Board spent £500,000 to modernize Norton Hill. This was meant to allow it to produce 315,000 tons of coal each year. However, there weren't enough workers, and geological problems caused the mine to close in 1966.

| Pits of the Norton Hill Collieries | |||||

| Colliery | Location | Opened | Closed | Max shaft depth (ft (m)) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Norton Hill New | Westfield | 1903 | 1966 | 1503 | |

| Norton Hill Old | Westfield | before 1839 | 1966 | 1247 | In 1908 10 men were killed in a major coal dust explosion. |

Nettlebridge Valley Mines

There were many coal mines in this area, from Gurney Slade east to Mells, around villages like Holcombe, Coleford, and Stratton-on-the-Fosse. These included at least 52 bell pits and 16 adits (tunnels). Some coal might have been mined here during Roman times and in the 1200s, making them some of the earliest mines in Somerset. Most mining ended in the 1800s. However, Strap Colliery opened in 1953 as Mendip Colliery and worked until 1969.

The Vobster Breach colliery had a special system of long coking ovens. These, along with other buildings, are now protected as a Scheduled monument. The chimney of Oxley's Colliery near Buckland Dinham, which operated in the 1880s, is a Grade II listed building.

| Pits of the Nettlebridge Valley | |||||

| Colliery | Location | Opened | Closed | Max shaft depth (ft (m)) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barlake | Nettlebridge | before 1819 | 1870 | 435 (132.6) | |

| Bilboa | Mells | ? | ? | 240 (73.2) | |

| Breach | Vobster | 1860 | c1880 | 867 (264.2) | |

| Charmborough | Holcombe | 1932 | 1947 | ? | |

| Coal Barton | Coleford | ? | ? | ? | Scene of a firedamp explosion which killed nine miners in 1869 |

| Edford | Holcombe | 1850s | 1915 | 798 (243.2) | |

| Holcombe | Holcombe | 1914 | 1923 | ? | |

| Luckington | Coleford | ? | ? | 135 (41.4) | |

| Mackintosh | Coleford | 1867 | 1919 | 1620 (493.8) | Merged with Newbury. 1896 owned by Westbury Iron Co. Ltd., |

| Mells | Mells | 1860s till 1880s | reopened 1909 till 1943 | 540 (164.6) | |

| Morewood Old | Nettlebridge | before 1824 | 1860s | 1247 (380) | |

| Morewood New | Nettlebridge | 1860s | 1932 | 888 (26.8) | |

| Nettlebridge | Nettlebridge | before 1831 | ? | 705 (214.9) | |

| Newbury | Coleford | 1799 | 1927 | 720 (219.4) | Merged with Mackintosh. 1896 owned by Westbury Iron Co. Ltd., 1908 Owned by John Wainwright and Co. Ltd. |

| New Rock | Stratton-on-the-Fosse | 1819 | 1968 | 1182 (360.3) | |

| Old Newbury | Coleford | c1710 | 1790s | 250 (76.2) | |

| Old Rock | Nettlebridge | 1786 | 1873 | 711 (216.7) | |

| Pitcot | Nettlebridge | before 1750 | c1820s | 555 (169.2) | |

| Strap (also known as Mendip or Downside Colliery) | Nettlebridge | 1863 | 1879 | 1838 (560.2) | Deepest shaft on the Somerset coalfield. Reopened in 1953 and worked until 1969. |

| Sweetleaze | Nettlebridge | before 1858 | 1879 | ? | |

| Vobster | Vobster | before 1850s | 1884 | 990 (301.8) | Had nationally unique long coking oven design. |

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |