Kennet and Avon Canal facts for kids

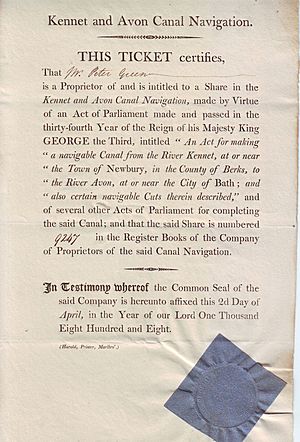

Quick facts for kids Kennet and Avon Canal |

|

|---|---|

The canal at Bathampton, near Bath

|

|

| Specifications | |

| Length | 87 miles (140 km) |

| Maximum boat length | 72 ft 0 in (21.95 m) |

| Maximum boat beam | 13 ft 6 in (4.11 m) |

| Locks | 105 |

| Maximum height above sea level | 450 ft (140 m) |

| Status | Open |

| Navigation authority | Canal & River Trust |

| History | |

| Construction began | 1718 |

| Date of first use | 1723 |

| Date completed | 1810 |

| Date restored | 1960s–1990 |

| Geography | |

| Start point | Bristol (Floating Harbour) |

| End point | Reading (River Thames) |

| Connects to | Somerset Coal Canal Wilts and Berks Canal |

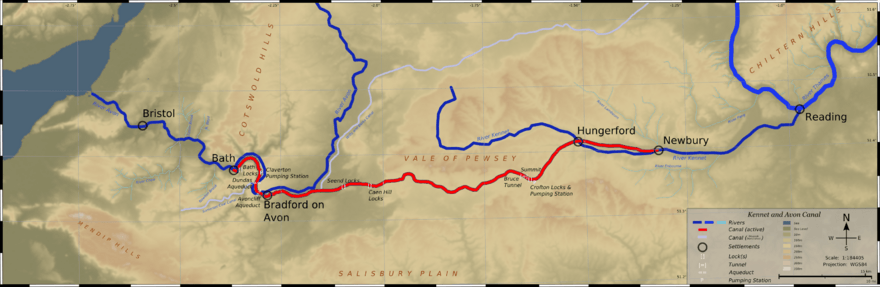

The Kennet and Avon Canal is a famous waterway in southern England. It is about 87 miles (140 km) long. This waterway connects two rivers: the River Avon and the River Kennet. It also includes a special canal section in the middle.

The waterway starts in Bristol and follows the River Avon to Bath. From Bath, the canal connects to the River Kennet near Newbury. Then, it follows the River Kennet to Reading, where it joins the River Thames. Along its whole length, there are 105 locks.

The river parts were made ready for boats in the early 1700s. The 57-mile (92 km) canal section was built between 1794 and 1810. Later, in the late 1800s and early 1900s, the canal was used less. This was because the Great Western Railway opened. But in the second half of the 1900s, many volunteers helped restore the canal. It was fully reopened in 1990. Today, the Kennet and Avon Canal is a popular place for fun activities. People enjoy boating, canoeing, fishing, walking, and cycling here. It is also very important for wildlife conservation.

History of the Canal

Early Ideas for a Waterway

People first thought about building a waterway across southern England in the late 1500s. They noticed that the Avon and Thames rivers were very close. In 1626, a mathematician named Henry Briggs explored the area. He saw that the land between the rivers was flat and easy to dig. He suggested building a canal to connect them.

However, his plan was not carried out. Later, after the English Civil War, new laws were proposed. But these plans failed because some powerful people were against them. Landowners and farmers worried that cheaper water transport would hurt their businesses. They feared it would reduce the money they made from toll roads. They also worried about cheaper food from Wales.

At that time, the main way to move goods between Bristol and London was by sea. This route through the English Channel was dangerous. Small sailing ships often faced bad storms. They also risked attacks from warships and privateers during wars with France.

The idea for a waterway was put aside until the early 1700s. In 1715, work began to make the River Kennet navigable. This meant making it deep enough for boats from Reading to Newbury. Work started in 1718, led by John Hore. The Kennet Navigation opened in 1723. It included natural river parts and 11 miles (18 km) of new cuts with locks.

The River Avon had been navigable from Bristol to Bath a long time ago. But in the 1200s, watermills were built, closing the river to boats. In 1727, the river was opened again. Six locks were built, also under John Hore's guidance. The first boat carrying goods reached Bath in December 1727.

These two river navigations were built separately. They met local needs. But they eventually led to plans to connect them. This would create a full route across England.

Connecting the Rivers

In 1788, people suggested a "Western Canal." This canal would improve trade and links to towns like Hungerford and Devizes. In 1793, John Rennie surveyed the route. The canal's path was changed to go through places like Great Bedwyn and Devizes.

The Kennet and Avon Canal Company accepted this new route. Construction began on April 17, 1794. The section from Newbury to Hungerford was finished in 1798. It reached Great Bedwyn in 1799. The part from Bath to Foxhangers was done in 1804. The Caen Hill Locks at Devizes were finished in 1810.

The canal fully opened in 1810 after 16 years of building. Important structures included the Dundas and Avoncliff aqueducts. There was also the Bruce Tunnel and pumping stations at Claverton and Crofton. These pumps were needed to keep enough water in the canal.

How the Canal Worked

Trade on the canal began in 1801. At first, goods had to be unloaded at Foxhangers. They were then moved up a hill by a horse-drawn railway. Then, they were reloaded onto barges at the top. When the locks opened in 1810, boats could travel the whole canal. This made trade much cheaper than by road. The canal became very busy.

By 1818, seventy large barges were working on the canal. Most of the goods were coal and stone. A trip from Bath to Newbury took about three and a half days. By 1832, 300,000 tons of goods were carried each year. The canal company made a lot of money.

Decline of the Canal

The opening of the Great Western Railway in 1841 greatly reduced the canal's traffic. Even though the canal company lowered its prices, people chose the railway. In 1852, the railway company took over the canal. They charged high fees and spent less money on keeping the canal in good shape.

Over time, rules were made that made it harder to use the canal. For example, boats could not travel at night. By 1868, the amount of goods carried had fallen sharply. The canal started losing money. Other canals that connected to the Kennet and Avon also closed. By 1926, the Great Western Railway wanted to close the canal completely. But people fought against this, and the railway had to improve its maintenance.

Cargo trade kept going down. But a few pleasure boats started to use the canal. During World War II, many concrete pillboxes were built along the canal. These were part of a defense line against a possible German invasion. Many of these pillboxes can still be seen today. After the war, large parts of the canal were closed because of poor maintenance. The last boat to travel the whole length was nb Queen in 1951.

Saving the Canal

In the early 1950s, a group was formed to save the canal. In 1955, a trader named John Gould successfully sued the canal's owners. He argued they failed to maintain the waterway. In 1956, a new law was proposed to remove the right to use the canal. But John Gould and local groups fought back. They gathered 22,000 signatures on a petition for the Queen.

This campaign led to a special committee looking into the issue. The committee suggested suspending navigation rights. But the House of Lords added a rule to the law. It said there should be "no further deterioration" of the canal. In 1959, a government report suggested the canal should be redeveloped. It set aside money for maintenance and restoration.

The Kennet and Avon Canal Trust was formed in 1962. Its goal was to restore the canal for everyone to use. In 1963, British Waterways took over the canal. They worked with the Trust and local councils. Restoration work then began.

Restoring the Canal

Restoration was a team effort. Staff from British Waterways worked with many volunteers. In 1966, Sulhamstead Lock was rebuilt. In 1968, work was done on the Bath Locks. A bridge in Reading was replaced to allow taller boats to pass. The canal from the Thames to Hungerford Wharf reopened in July 1974.

The Avoncliff Aqueduct was made watertight in 1980. More work continued in the 1980s. Local councils helped pay for new bridges. There were worries about enough water for the highest part of the canal. So, pumps were needed to move water uphill.

Many fundraising events helped pay for the work. In 1983, a program helped employ 50 men for restoration. They worked on Aldermaston Lock and Widmead Lock. The Dundas Aqueduct was also restored. New lock gates were made for the Crofton and Devizes locks. In 1988, the restoration of Woolhampton Lock was finished.

The section between Reading and Newbury was completed on July 17, 1990. Queen Elizabeth II officially reopened the canal on August 8, 1990. She traveled through some of the Caen Hill Locks. In 1996, new pumps were installed at Caen Hill. These pumps raise water 235 feet (72 m) to the top of the locks.

In October 1996, the canal received a huge grant from the National Lottery. This money helped finish the restoration. It also made sure the canal would be used and enjoyed for years to come. The restoration was celebrated in May 2003 by HRH Prince Charles. Work to improve and maintain the canal continues today. In 2011, the canal was named a national "cruiseway." This means it must be kept open for boats.

The Canal Route

Bristol to Bath Section

The River Avon was used by boats from Bristol to Bath in the 1200s. But mills built on the river later closed it. Today, the Avon is navigable from its mouth at Avonmouth. It goes through the Floating Harbour in Bristol. It continues to Pulteney Weir in Bath.

Beyond Pulteney Weir, the Avon is still navigable to Bathampton. The stretch from Bristol to Bath has locks and weirs. These help boats go up 30 feet (9 m) over 12 miles (19 km).

Hanham Lock was the first lock on the Avon Navigation, opened in 1727. It is the first lock east of Netham, near Bristol. The river below Hanham Lock is affected by tides. High tides can pass over the weir at Netham. Sometimes, spring tides go over the weir at Hanham. This makes the river tidal up to Keynsham Lock.

Heading east, the river passes the Somerdale Factory. This was a chocolate factory for Cadbury. On the north bank is Cleeve Wood. This area is important for a plant called Bath asparagus. A pub is built on an island between Keynsham Lock and the weir. The River Chew also joins here.

The river then goes through Avon Valley Country Park. It passes Stidham Farm, which has old river gravels. These gravels contain limestone and other rocks. The river goes under an old railway line. This line is now the Avon Valley Railway, a 3-mile (4.8 km) heritage railway.

Next is Swineford Lock. From 1709 to 1859, there was a busy brass and copper industry here. The river provided water power for cloth making. The remains of Kelston Brass Mill are next to Saltford Lock. This lock opened in 1727. But rival coal dealers destroyed it in 1738.

The Bristol and Bath Railway Path crosses the river several times. It reaches Newbridge on the edge of Bath. Here, the A4 road crosses near Newton St Loe SSSI. This site has important Pleistocene gravels. They contain fossils of mammoths and horses. These fossils help scientists understand the history of glaciation in England. The last lock before Bath is Weston Lock, opened in 1727. It created an island called Dutch Island.

Bath to Devizes Section

The Bath Bottom Lock is where the River Avon and the canal separate. It is south of Pulteney Bridge. Near this lock is a pumping station. It pumps water "upstream" to replace water used by boats. The next lock is Bath Deep Lock. It is numbered 8/9 because two locks were combined in 1976. This new lock is 19 feet 5 inches (5.92 m) deep. It is the second-deepest canal lock in the UK.

Above the Deep Lock is another water storage area. Then comes Wash House Lock. After a longer section, there is Abbey View Lock. Another pumping station is nearby. Then, quickly, come Pulteney Lock and Bath Top Lock.

Above the Top Lock, the canal goes through Sydney Gardens. It passes through two short tunnels. Two cast iron footbridges from 1800 are also here. Cleveland Tunnel is 173 feet (53 m) long. It runs under Cleveland House. This building was once the main office of the Kennet and Avon Canal Company. A trap-door in the tunnel roof was used to pass papers between clerks and boatmen. Many bridges over the canal are historic buildings.

On the east side of Bath, a toll bridge connects Bathampton to Batheaston. When the A4 bypass was built, Bathampton Meadow was created. This 22-acre (8.9 ha) area helps with flood relief. Its wet meadows attract many birds. These include wading birds like dunlin and ringed plover. Sand martins and kingfishers are often seen by the lake.

The canal turns south into a valley. This valley is between Bathampton Wood and Bathford Hill. It includes Brown's Folly, a 99-acre (40 ha) special scientific site. In the Avon Valley, east of Bath, you can see all four types of transport: road, rail, river, and canal.

The canal passes an old loading dock. This dock was used for Bath Stone from nearby quarries. The stone was brought down a track to the canal. Next, the canal passes the Claverton Pumping Station. This station uses a waterwheel to pump water from the River Avon into the canal. The building was finished in 1810.

On the east bank, Warleigh Wood and Inwood are woodlands. They come right down to the canal.

The canal then crosses the river and railway at the Dundas Aqueduct. It passes Conkwell Wood. Then it crosses the river and railway again at the Avoncliff Aqueduct. At the west end of Dundas Aqueduct, the remains of the Somerset Coal Canal join. A small part of it has been restored. This created the Brassknocker Basin. The Somerset Coal Canal was built around 1800. It gave access to London from the Somerset Coalfield.

After the Avoncliff Aqueduct, the canal goes through Barton Farm Country Park. It passes a 14th-century tithe barn. This barn is 180 feet (55 m) long and 30 feet (9.1 m) wide. Then it goes into Bradford on Avon.

The first ground for the Kennet and Avon Canal was dug in Bradford on Avon in 1794. Soon, there were wharves above and below Bradford Lock. Further east, an aqueduct carries the canal over the River Biss. There are locks at Semington and Seend. Water flows into the canal here from the Summerham Brook.

In Semington, the Wilts & Berks Canal joined the canal. This linked the Kennet and Avon to the River Thames at Abingdon. The 52-mile (84 km) canal opened in 1810. But it was abandoned in 1914. In 1977, a group was formed to restore it. They want to reconnect the Kennet and Avon to the Thames.

The Caen Hill Locks at Devizes show amazing engineering. The main group of 16 locks takes 5–6 hours to go through by boat. They are part of a longer series of 29 locks. These locks climb 237 feet (72 m) in 2 miles (3.2 km). This is a very steep slope.

The locks were the last part of the canal to be finished. The land was so steep that there was no room for normal water sections between locks. So, the 16 locks use very large side ponds to store water. A large pump was installed in 1996. It can return 7 million imperial gallons (32,000 m³) of water per day to the top. This is like one lockful every 11 minutes.

While the locks were being built, a railway moved goods between the top and bottom. The remains of this railway can be seen in the bridges. From 1829 to 1843, the locks were lit by gas lights. Lock 41 is the narrowest lock on the canal.

At the top of the locks is Devizes Wharf. This is home to the Kennet & Avon Canal Museum. It shows how the canal was planned, built, used, and then declined. It also shows its restoration. The museum is run by the Kennet and Avon Canal Trust. Devizes Wharf is also the start of the Devizes to Westminster International Canoe Marathon. This race has been held since 1948.

Devizes to Newbury Section

East of Devizes, the canal goes through the countryside of Wiltshire. It passes several locks and swing bridges. Then there is another group of locks at Crofton.

At Honeystreet are the remains of a wharf. This was once home to boat builders Robbins, Lane and Pinnegar. They built many boats for canals in southern England. Next to the wharf is the Barge Inn. This large public house was once called the George Inn. It was about halfway along the canal. It served as a bakery, butcher shop, and store for boat workers. The building burned down in 1858 but was rebuilt quickly.

Jones's Mill is a 29-acre (12 ha) area of fen, scrub, and woodland. It is along the Salisbury Avon northeast of Pewsey. It is a special scientific site because it has a rare type of wetland.

The four locks at Wootton Rivers are the end of the climb from the Avon. Between Wootton Top Lock and Crofton is the highest point of the canal. It is 450 feet (137 m) above sea level. This section is about 2 miles (3.2 km) long. It includes the 502-yard (459 m) Bruce Tunnel. The tunnel is named after the local landowner, Thomas Brudenell-Bruce, 1st Earl of Ailesbury. He did not want a deep cut through his land. So, he insisted on a tunnel.

The tunnel has red brick entrances with Bath stone. It was started in 1806 and finished in 1809. It is wide enough for the large Newbury barges. There is no towpath through the tunnel. So, walkers and cyclists must go over the hill. In the past, boatmen had to pull their barges through the tunnel by hand. They pulled on chains along the walls.

The Crofton Locks mark the start of the descent to the Thames. The nine locks drop 61 feet (19 m). When the canal was built, there were no easy ways to fill the summit with water. Springs were found nearby, but they were lower than the canal. So, they were used to feed the pound below lock 60 at Crofton. Later, the Wilton Water reservoir was built to add more water.

Water is pumped to the summit from Wilton Water by the Crofton Pumping Station. This old steam-powered station has one of the oldest working Watt-style beam engines in the world. It dates from 1812. The steam engines still pump water on some weekends. But for daily use, electric pumps are used. They are controlled automatically by the water level.

Near Crofton is Savernake Forest. There are also remains of a railway bridge that crossed the canal. Mill Bridge at Great Bedwyn is unusual. It is a skew arch, the first of its kind when finished in 1796. From there to Hungerford, the canal follows the River Dun. It goes through Freeman's Marsh. This area has meadows, marsh, and reedbeds. It is important for birds and rare plants.

There are plans for a marina and hotel nearby. But people worry about how this might affect the wildlife. Especially the water voles. To the north of the canal are seven small areas. These make up the Kennet and Lambourn Floodplain SSSI. They are home to many Desmoulin's whorl snails.

There are several locks and bridges in Hungerford. Hungerford Marsh Lock is special. It has a swing bridge directly over the lock. This bridge must be opened before the lock can be used. In the area around the lock, called Hungerford Marsh Nature Reserve, over 120 bird species have been seen.

Between Kintbury Lock and Newbury, the canal is very close to the River Kennet. The river flows into the canal in several places. The canal passes through the Kennet Valley Alderwoods. These are important woodlands with many different plants. They are dominated by alder trees.

Irish Hill Copse is nearby. This old woodland has ash and elm trees. It also has oak and hazel trees. The lower parts have plants like dog's mercury and herb paris.

A wooden bridge was built over the Kennet at Newbury in 1726. It was replaced by a stone bridge between 1769 and 1772. This is now called the Town Bridge. There is no towpath here. So, the rope to pull the barge had to be floated under the bridge. Then it was re-attached to the horse.

Newbury to Reading Section

The River Kennet is navigable from Newbury to where it meets the River Thames in Reading. This section is called the Kennet Navigation. It opened in 1723. It has natural river parts and 11 miles (18 km) of new cuts. There are also locks that drop 130 feet (40 m).

East of Newbury, the Kennet goes through the Thatcham Reed Beds. This 169-acre (68 ha) area is important for its large reedbeds. It also has rich alder woodland and fen habitats. It is home to the Desmoulin's whorl snail. Many birds breed here, including rare species like Cetti's warbler. The area is managed as The Nature Discovery Centre by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds.

Monkey Marsh Lock at Thatcham is one of only two turf-sided locks left on the canal. It is a protected historic site.

Below Colthrop Lock in Thatcham, the river leaves Newbury's built-up area. It flows through rural areas. It passes through the Woolhampton Reed Bed. This is another special scientific site. It has dense reedbeds and fen vegetation. It is known for its many insects and nesting birds. These include reed warblers.

Aldermaston Gravel Pits are old flooded gravel workings. They are surrounded by plants and trees. This creates many habitats for birds. It is a refuge for wildfowl. The irregular shoreline and islands provide quiet places for water birds. These include ducks like teal and shoveler. The surrounding marsh is important for many birds. These include nine types of warblers and nightingales. In 2002, English Nature bought the gravel pits. They are now managed as a nature reserve.

The River Kennet itself, from Marlborough to Woolhampton, is a special scientific site. This is because it has many rare plants and animals. These are unique to chalk rivers.

The village of Woolhampton and Aldermaston Wharf are the only big settlements. Then the river enters Reading at Sheffield Lock in Theale. Even here, the river is separated from Reading's suburbs by a wide floodplain. In this section is Garston Lock. This is the other turf-sided lock on the canal.

After Fobney Lock, the Kennet floodplain narrows. The river enters a steep gap in the hills. At County Lock, the river enters the center of Reading. It used to flow through a large brewery. This narrow, twisting part of the river was called Brewery Gut. Because it was hard to see and boats struggled to pass, traffic lights controlled it. Today, Brewery Gut is a main feature of Reading's The Oracle shopping center.

Right after The Oracle, the river flows under the arched High Bridge. This bridge is a historical divide on the river. The last 1 mile (1.6 km) of the River Kennet in Reading has been navigable since the 1200s. There was no wide floodplain here. So, wharves could be built. This helped Reading become a river port. This short section of river, including Blake's Lock, was once controlled by Reading Abbey. Today, the Environment Agency manages it. The Horseshoe Bridge at Kennet Mouth was built as a railway bridge in 1839.

The Canal Today

Today, the canal is a popular place for heritage tourism. Boating with narrowboats and cruisers is a favorite activity. This is especially true in the summer. Famous canal fans like Prunella Scales and Timothy West enjoy it.

Many private boats and hire boats use the canal. There are also many canoe clubs. The yearly Devizes to Westminster International Canoe Marathon starts from Devizes Wharf. This is where the Kennet & Avon Canal Museum is located. The race starts on Good Friday. Competitors must go through 75 locks on the 125-mile (201 km) route. The race ends at Westminster. The winning time is usually around 17 and a half hours.

Cycling is allowed on the towpath. There is a short section near Woolhampton where it is not allowed. Some parts of the towpath have been improved. They are now better for cyclists and people with disabilities. Two main sections of the canal are part of the National Cycle Network (NCN) Route 4. These run from Reading to Marsh Benham and from Devizes to Bath.

Fishing is allowed all year from the towpath. You can catch fish like bream, tench, roach, rudd, perch, gudgeon, pike, and carp. Most of the canal is leased to fishing clubs. There are many public houses, shops, and tea rooms along the canal. The Kennet and Avon Canal Trust runs shops and tea rooms. These are at Aldermaston Lock, Newbury Wharf, Crofton Pumping Station, Devizes, and Bradford on Avon.

Wildlife on the Canal

The canal and its surroundings are very important for wildlife. There are several Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI). These places have many different kinds of plants and animals. Key sites include the Aldermaston Gravel Pits, Woolhampton, Thatcham Reed Beds, and Freeman's Marsh, Hungerford. There are also many other nature reserves along the canal.

More than 100 different bird species have been seen along the canal. Thirty-eight of these are special waterway birds. These include grey herons, reed buntings, and common kingfishers. Fourteen species have been confirmed as breeding here. This includes sand martins, which nest in drain-pipes in Reading.

Wilton Water near Crofton Locks and the Kennet Valley gravel pits are home to many water birds. Several types of Odonata (dragonflies and damselflies) and other insects have also been recorded. Common reed grows along the canal edges. Efforts to protect and create homes for water voles have been very important. New ways of protecting the canal banks have been developed to help these animals.

See also

In Spanish: Canal del Kennet y del Avon para niños

In Spanish: Canal del Kennet y del Avon para niños

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |