Sailing ship facts for kids

A sailing ship is a large boat that uses big pieces of fabric called sails. These sails catch the wind to make the ship move across the water. There are many different ways sails can be set up on a ship, called "sail plans." Some ships have square sails on every mast, like a brig or a full-rigged ship. Others have sails that run front-to-back on every mast, like some schooners. And some ships use a mix of both square and front-to-back sails, such as the barque, barquentine, and brigantine.

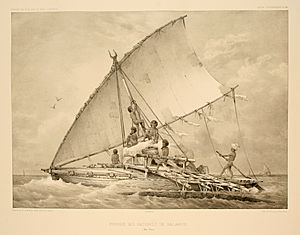

The first sailing ships were used in rivers and along coasts in Ancient Egypt and the Mediterranean Sea. Later, people from Austronesia (islands in the Pacific and Indian Oceans) invented special sails called "crab-claw sails." They also built boats with two hulls (catamarans) or outriggers (side floats). These inventions helped them explore and settle many islands, starting from Taiwan around 3000 BC. They reached Hawaii around 900 AD and New Zealand around 1200 AD.

In Asia, ships like the junk and dhow were developed. These ships had features that Europeans didn't know about at the time. European sailing ships, mostly with square sails, became very important during the Age of Discovery (from the 1400s to 1600s). These ships sailed across oceans and even around the world. During the European Age of Sail, many sailing ships were merchant ships that carried goods. But there were also large fleets of powerful warships.

In the 1800s, steamships started to compete with sailing ships. At first, steamships were only good for short trips. But by the 1880s, steamships with better engines could travel long distances and keep to a schedule, no matter the wind. Even so, some commercial sailing ships were still used into the 1900s, though their numbers slowly decreased.

Contents

How Sailing Ships Changed Over Time

Sailing ships have a long and exciting history. They changed a lot from ancient times to the modern day.

Early Ocean Voyages

By the 1400s, during the Age of Discovery, large ships with multiple masts and square sails were common. Sailors used tools like the magnetic compass and observed the sun and stars to guide them across oceans. The Age of Sail was busiest in the 1700s and 1800s, with huge, armed battleships and many merchant sailing ships.

Sailing ships and steamships were both used for a long time in the 1800s. Early steamships used a lot of fuel and were mostly for short trips or towing sailing ships. But both types of ships got much better over time. By the 1880s, steamships became very fuel-efficient. This meant they could compete with sailing ships on almost all trade routes. However, some commercial sailing ships continued to operate until about 1960.

Ships from Asia and the Pacific

The first ocean-going sailing ships were used by the Austronesian peoples. They invented catamarans (boats with two hulls), outriggers (side floats), and crab claw sails. These inventions helped them spread across the islands of Southeast Asia, Micronesia, Melanesia, Polynesia, and even Madagascar, starting around 3000 to 1500 BC. Austronesian sails were special because they had poles supporting both the top and bottom edges of the sails.

Large Austronesian trading ships with up to four sails were mentioned by Chinese scholars around 200 BC. These ships were called kunlun bo and were used by Chinese Buddhist travelers to reach India and Sri Lanka. Stone carvings from the 8th century in Java also show large Javanese ships with outriggers and special sails.

By the 900s AD, the Song Dynasty in China started building the first Chinese junks. These ships borrowed ideas from the kunlun bo. The junk rig became famous for Chinese trading ships that sailed along the coast. Chinese junks were built from strong wood like teak, using pegs and nails. They had special watertight sections and rudders in the middle. These junks were later used as warships by the Mongols during their attempts to invade Japan and Java.

During the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), junks were used for long-distance trade. The famous Chinese Admiral Zheng He sailed to India, Arabia, and southern Africa on trade and diplomatic trips. Stories say his biggest ship, the "Treasure Ship," was about 400 feet (120 meters) long. However, modern research suggests it was more likely around 230 feet (70 meters) long.

Ships from Europe

Sailing ships in the Mediterranean Sea go back to at least 3000 BC. The ancient Egyptians used a mast with two poles to hold a single square sail. These boats mostly used paddlers. Later, the mast became a single pole, and oars replaced paddles. These ships sailed on the Nile River and along the Mediterranean coast.

From 1000 BC to 400 AD, the Phoenicians, Greeks, and Romans built ships powered by square sails. They sometimes used oars to help. These ships used a steering oar to control direction.

Starting in the 700s AD in Denmark, Vikings built strong longships. These ships had a single square sail and also used oars when needed. A similar ship, the knarr, sailed in the Baltic and North Seas, mainly using wind power.

Ships from the Indian Ocean

India's sea history began around 3000 BCE, when people from the Indus Valley started trading by sea with Mesopotamia. Indian kingdoms like Kalinga are thought to have had sailing ships as early as the 100s AD. One of the oldest pictures of an Indian sailing ship is a mural of a three-masted ship in the Ajanta caves, from 400-500 AD.

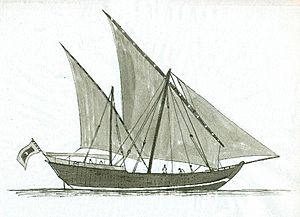

Between 1200 and 1500, trade increased between India and Africa across the Indian Ocean. The ships used were called dhows, with lateen rigs (triangular sails). During this time, dhows grew in size, from carrying 100 to 400 tons of goods. Dhows were often built from teak wood planks sewn together with coconut fibers, without using nails. This period also saw the use of rudders in the middle of the ship, controlled by a tiller.

Ships for Global Exploration

Two big advancements helped with global exploration in the 1400s: the magnetic compass and better ship designs.

The compass helped sailors find their direction. It was invented by the Chinese and used in China by the 1000s. Arab traders in the Indian Ocean then adopted it. The compass reached Europe by the late 1100s or early 1200s. Europeans used a "dry" compass with a needle on a pivot.

At the start of the 1400s, the carrack was the best European ship for ocean travel. It was built strongly and was big enough to be stable in rough seas. It could carry a lot of cargo and supplies for very long trips. Later carracks had square sails on the front and main masts, and a lateen (triangular) sail on the back mast. They had a high, rounded back and a bowsprit (a pole sticking out from the front). The carrack was a very important ship design, leading to the galleon.

Ships from this time could not sail directly into the wind. They had to sail at an angle, making it hard to avoid shipwrecks near land during storms. Still, these ships reached India by sailing around Africa with Vasco da Gama, the Americas with Christopher Columbus, and sailed around the world with Ferdinand Magellan.

Ships from 1700 to 1850

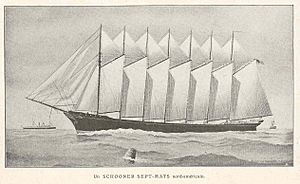

Sailing ships became longer and faster over time. Ships with square rigs had taller masts and more square sails. Other sail plans also appeared, like schooners (all front-to-back sails) or ships with a mix of both, such as brigantines, barques, and barquentines.

Warships

Cannons were first used in the 1300s, but they didn't become common on ships until they could be reloaded quickly during a battle. The large size of ships needed to carry many cannons meant they couldn't use oars anymore. Warships then relied mainly on sails. The sailing man-of-war appeared in the 1500s.

By the mid-1600s, warships carried more and more cannons on three decks. Naval tactics changed to use the ships' firepower in a "line of battle"—where a fleet of warships moved in a line to fight the enemy. Earlier ships like carracks became galleons, then men-of-war, and finally the ship of the line. These ships were designed to fire all their cannons from one side (broadside) at enemy ships. In the 1700s, smaller, faster ships like the frigate and sloop-of-war were developed. They were too small for the line of battle but were used to protect trade, scout for enemies, and block enemy coasts.

Clippers

The word "clipper" started being used in the early 1800s for sailing ships built for speed. Only a small number of sailing ships were true clippers.

Early clippers were Baltimore clippers, used to sneak past blockades or as privateers (armed ships allowed to attack enemy ships) during the War of 1812. Later, larger clippers were built for the California Gold Rush after gold was found in 1848. These ships sailed from the east coast of the USA to San Francisco.

Clippers were also built for trade between the United Kingdom and China, especially for carrying tea. These "tea clippers" were the fastest way to transport tea until fuel-efficient steamships and the Suez Canal opened in 1869.

Clippers were usually built for specific routes. For example, California clippers had to handle the rough seas around Cape Horn. Tea clippers were designed for the lighter winds of the China Sea. All clippers had sleek designs and large sail areas. They needed a skilled captain to get the most speed out of them.

Protecting Ship Hulls

During the Age of Sail, ship hulls were often damaged by shipworms (which ate the wood) and covered by barnacles and weeds (which slowed the ship down). For centuries, people tried different coatings like tar and wax. In the mid-1700s, copper sheathing was developed. This meant covering the bottom of the hull with copper sheets to protect it. At first, there were problems with the copper reacting with metal fasteners on the hull. But then, "sacrificial anodes" were invented. These were pieces of metal that would corrode instead of the hull fasteners. Copper sheathing became common on naval ships in the late 1700s and on merchant ships in the early 1800s, until iron and steel hulls became popular.

After 1850

Iron-hulled sailing ships, also called "windjammers" or "tall ships," were the last big step in sailing ship design at the end of the Age of Sail. They were built to carry large amounts of cargo over long distances in the late 1800s and early 1900s. These were the biggest merchant sailing ships, with three to five masts and square sails, as well as other sail plans. They carried lumber, guano (bird droppings used as fertilizer), grain, or ore between continents. Later, they had steel hulls instead of iron.

Iron-hulled sailing ships were mostly built from the 1870s to 1900. After that, steamships became more economical because they could keep a schedule no matter the wind. Even in the 1900s, sailing ships could still compete on long ocean trips, like from Australia to Europe. This was because they didn't need to carry coal or fresh water for steam, and they were faster than early steamships.

The four-masted, iron-hulled ship, first seen in 1875, was very efficient. This helped sailing ships compete with steamships longer. The largest of these was the five-masted, full-rigged ship Preussen, which could carry 7,800 tons. The Preussen used steam power for its winches and pumps, and only needed a crew of 48. In comparison, a four-masted ship like Kruzenshtern needed a crew of 257.

In the 20th century, the DynaRig was invented. This system allows all sails to be controlled automatically from a central point, so sailors don't have to climb up the masts. It was developed in Germany in the 1960s as a way for commercial ships to use less fuel. The mast rotates to line up the sails with the wind. Modern yachts like Maltese Falcon and Black Pearl use this system.

In the 21st century, because of worries about climate change and the desire to save money, companies are looking into using wind power again for large container ships. By 2023, about 30 ships were using sails or large kites to help them move, and this number is expected to grow.

Parts of a Sailing Ship

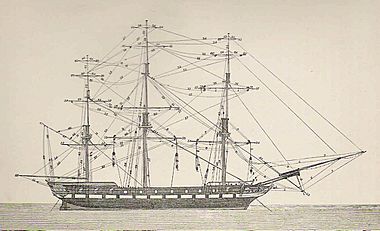

Every sailing ship has a special "sail plan" that fits its purpose and the crew's skills. Each ship has a hull (the main body), rigging (ropes and wires), and masts to hold up the sails. The masts are held in place by strong ropes called standing rigging, and the sails are adjusted by other ropes called running rigging.

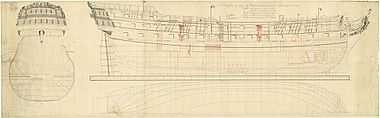

The Hull

The shape of ship hulls changed over time. Early hulls were short and blunt, but later ones became longer and thinner at the front. By the 1800s, ships were built using "half models" made of wooden layers. Each layer could be used to figure out the actual size of the ship's structure, starting with the keel (the backbone) and then the ribs. The ribs were put together from curved pieces and held in place until the outer planks were added. The planks were sealed with tar-soaked yarn to make them watertight. In the mid-1800s, iron started to be used for the hull structure and then for the watertight outer layer.

The Masts

Until the mid-1800s, all ship masts were made of wood, either from a single tree or several pieces joined together. From the 1500s, ships became so big that their masts needed to be taller and thicker than a single tree trunk. On these larger ships, masts were built from up to four sections, stacked one on top of the other: the lower mast, top mast, topgallant mast, and sometimes the royal mast. The lower sections were made from several pieces of wood joined together. Later, in the second half of the 1800s, masts were made of iron or steel.

For ships with square sails, the main masts from front to back are:

- Fore-mast: The mast closest to the front of the ship. It has sections like the fore-mast lower, fore topmast, and fore topgallant mast.

- Main-mast: The tallest mast, usually in the middle of the ship. It has sections like the main-mast lower, main topmast, main topgallant mast, and sometimes a royal mast.

- Mizzen-mast: The mast at the very back of the ship. It is usually shorter than the fore-mast and has sections like the mizzen-mast lower, mizzen topmast, and mizzen topgallant mast.

The Sails

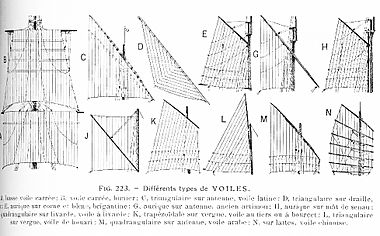

Each ship's sails are arranged in a "sail plan" that fits its size and purpose. Both square-rigged and front-to-back rigged ships have many different sail setups, whether they have one mast or many.

Sails can be attached to the ship in different ways:

- To a stay: These sails are attached to strong ropes or wires called "stays" that support the masts. Examples include jibs (at the front) and staysails (on other stays).

- To a mast: Front-to-back sails can be directly attached to the mast along their front edge. Examples include gaff-rigged (four-sided) and Bermuda (triangular) sails.

- To a spar: These sails are attached to a pole called a "spar." This includes square sails and front-to-back sails like lug rigs, junk sails, spritsails, and triangular sails like the lateen and crab claw.

The Rigging

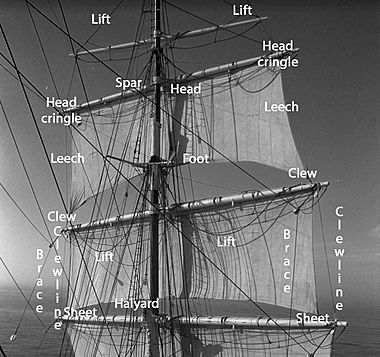

Sailing ships have standing rigging to support the masts and running rigging to raise the sails and control how they catch the wind. Running rigging helps support the sail, shape it, and adjust its angle to the wind. Square-rigged ships need more control ropes than front-to-back rigged ones.

Standing Rigging

Before the mid-1800s, sailing ships used wooden masts with standing rigging made of hemp fiber. As rigs got taller in the late 1800s, masts were built from several sections stacked on top of each other: the lower mast, top mast, and topgallant mast. This design needed a lot of stays (ropes running front-to-back) and shrouds (ropes running side-to-side) for support. Each stay had another one pulling in the opposite direction to keep tension. Shrouds were tightened using pairs of "deadeyes," which were round blocks with holes for ropes to pass through. After the mid-1800s, square-rigged ships used iron wire for standing rigging, which was later replaced by steel wire.

Running Rigging

Halyards are ropes used to raise and lower the yards (horizontal poles that hold square sails). Square rigs also have ropes that lift the sail or the yard, such as brails, buntlines, lifts, and leechlines. Bowlines and clew lines help shape a square sail. To change the angle of the sail to the wind, braces adjust the angle of a yard for square sails. Sheets attach to the bottom corners (clews) of a sail to control its angle to the wind. Sheets run towards the back of the ship, while tacks pull the bottom corner of a square sail forward.

The Crew

The crew of a sailing ship is made up of officers (the captain and his helpers) and sailors. An experienced sailor was expected to "hand, reef, and steer"—meaning they could handle ropes and equipment, reduce the size of sails, and steer the ship. The crew worked in shifts called "watches," usually four hours long. Writers like Richard Henry Dana Jr. and Herman Melville wrote about their own experiences on sailing ships in the 1800s.

Merchant Ship Crew

Dana described the crew of the merchant brig Pilgrim. It had six to eight common sailors, four specialists (the steward, cook, carpenter, and sailmaker), and three officers: the captain, the first mate, and the second mate. He noted that American ships had smaller crews compared to similar-sized ships from other countries, which might have up to 30 people. Larger merchant ships had more crew members.

Warship Crew

Melville described the crew of the frigate warship United States as about 500 people. This included officers, enlisted personnel, and 50 Marines. The crew was divided into two watches: starboard and larboard. They were also divided into three "tops" (groups responsible for setting sails on the three masts). Other groups included "sheet-anchor men" (who handled the front sails and anchors), the "after guard" (who handled the main sails at the back), and the "waisters" (who had less important duties). There were also "holders" who worked on the lower decks. Other roles included boatswains, gunners, carpenters, cooks, and various boys. In the 1700s and 1800s, large ships of the line could have up to 850 crew members.

How to Sail a Ship

Sailing a ship means managing its sails to get power without damaging the ship. It also means navigating to guide the ship, both on the open sea and in and out of harbors.

Sailing on the Water

Key parts of sailing a ship are setting the right amount of sail to get the most power, adjusting the sails for the wind direction, and changing direction to let the wind come from the other side of the ship.

Setting the Sails

A sailing ship's crew manages the ropes for each square sail. Each sail has two sheets (for the bottom corners), two braces (for the yard's angle), two clewlines, four buntlines, and two reef tackles. All these ropes must be handled as the sail is put up and the yard is raised. They use a halyard to raise each yard and its sail. Then they pull or loosen the braces to set the yard's angle across the ship. They pull on sheets to bring the lower corners of the sail, called clews, out to the yard below. While sailing, the crew uses reef tackles, haul leeches, and reef points to control the size and angle of the sail. Bowlines pull the front edge of the sail tight when sailing close to the wind. When folding the sail, the crew uses clewlines to pull up the clews and buntlines to pull up the middle of the sail. When the sail is lowered, lifts support each yard.

In strong winds, the crew is told to reduce the number of sails or make each sail smaller. This is called reefing. To pull the sail up, sailors on the yardarm pull on reef tackles, which are attached to reef cringles. They pull the sail up and tie it with ropes called reef points. Dana wrote about how hard it was to handle sails in strong wind and rain, or when ice covered the ship and its ropes.

Changing Direction

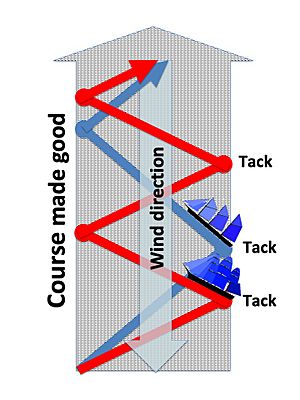

Sailing ships cannot sail directly into the wind. Square-rigged ships must sail at an angle of 60° to 70° away from the wind. Front-to-back rigged ships can usually sail no closer than 45° to the wind. To reach a destination, sailing ships often have to change course and let the wind come from the opposite side. This is called tacking, and it means the wind crosses the front of the ship during the turn.

When tacking, a square-rigged ship's sails must be turned to face the wind squarely. This slows the ship down as the yardarms are swung around by the running rigging. Braces adjust the front-to-back angle of each yardarm around the mast. Sheets attached to the bottom corners (clews) of each sail control the sail's angle to the wind. The ship turns into the wind, using the back-most front-to-back sail (the spanker) to help turn the ship through the wind. Once the ship has turned, all sails are adjusted for the new direction. Tacking can be risky in strong winds because the ship might lose speed or the rigging might break if the wind hits it from the front. If the wind is too light (less than 10 knots), the ship might also lose momentum. In these cases, the crew might choose to wear ship—turning the ship away from the wind and then around 240° to the next direction.

A front-to-back rig allows the wind to flow past the sail as the ship turns through the wind. Most of these rigs pivot around a stay or the mast during this turn. For a jib, the rope on the downwind side is released as the ship turns, and the rope on the upwind side is tightened to catch the wind. Mainsails often move automatically on a track to the other side. On some rigs, like lateens, the sail might be partly lowered to move it to the other side.

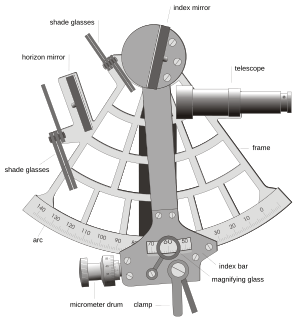

Early sailors used observations of the sun, stars, waves, and birds to navigate. In the 1400s, the Chinese used the magnetic compass to find direction. By the 1500s in Europe, navigation tools included the quadrant, astrolabe, cross staff, dividers, and compass. During the Age of Exploration, these tools were used with a log (to measure speed), a lead line (to measure water depth), and a lookout (to spot dangers). Later, an accurate marine sextant became standard for finding latitude (how far north or south you are). This was used with an accurate chronometer (a very precise clock) to calculate longitude (how far east or west you are).

Passage planning starts by drawing a route on a chart. This route has a series of directions between "fixes"—places where the ship's exact location can be confirmed. Once a course is set, the person steering tries to follow that direction using the compass. The navigator notes the time and speed at each fix to guess when they will reach the next fix. This is called dead reckoning. For sailing near the coast, sailors use sightings from known landmarks or navigational aids to find their position. This is called pilotage. At sea, sailing ships used celestial navigation (using stars and sun) every day. They would:

- Keep a continuous dead reckoning plot (guessing their position).

- Observe stars at dawn for an exact position.

- Observe the sun in the morning to check the compass.

- Observe the sun at noon to find their latitude and how far they traveled.

- Observe the sun in the afternoon to check the compass again.

- Observe stars at dusk for another exact position.

Positions were taken with a marine sextant, which measures the height of a celestial body above the horizon.

Entering and Leaving Harbors

Because sailing ships were not very easy to maneuver, it could be hard to enter and leave a harbor with tides. Ships often had to time their arrivals with a rising tide and their departures with a falling tide. In a harbor, a sailing ship would usually stay at anchor. If it needed to load or unload at a dock, it might be "warped" alongside or towed by a tugboat. Warping involved using a long rope (the warp) between the ship and a fixed point on shore. This rope was pulled by a capstan (a rotating machine) on shore or on the ship. If there was no fixed point, a smaller anchor might be taken out in a boat and dropped, then the ship would pull itself up to that anchor. Square-rigged ships could use their sails to maneuver in tidal waters, or they could control their movement by "drudging the anchor"—lowering the anchor until it dragged on the bottom, which helped steer the ship with the tide's flow.

Types of Sailing Ships

Here are some examples of sailing ships. Some names might have more than one meaning.

|

Named by General Design

|

Named by Sail Plan All masts have front-to-back sails

All masts have square sails

Mix of masts with square sails and masts with front-to-back sails

Military Ships

|

See also

In Spanish: Embarcación de vela para niños

In Spanish: Embarcación de vela para niños

- List of large sailing vessels

- Sailboat

- Sailing ship accidents

- Sailing ship effect—how old and new technologies change

- Sailing ship tactics

- Shipbuilding

- Tall ship

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |