Mining in Roman Britain facts for kids

Mining was a super important activity in Roman Britain. Britain had lots of valuable resources like copper, gold, iron, lead, salt, silver, and tin. These materials were in high demand across the huge Roman Empire. The Romans needed a steady supply of metals for making coins and fancy items for rich people. They even started looking for gold by panning in rivers. Britain's rich mineral resources were probably a big reason why the Romans decided to conquer the British Isles. They used amazing technology to find and dig up these valuable minerals, more than anyone had done before the Middle Ages.

Contents

Lead Mining in Roman Britain

Lead was super important for the Roman Empire to run smoothly. They used it for piping in aqueducts (water channels) and plumbing, for making pewter (a metal alloy), coffins, and even gutters for their large villas. Lead was also important because it often contained silver, which the Romans needed a lot. For example, 52 sheets of lead from the Mendip Hills still line the great bath at Bath, not far from Charterhouse.

The biggest Roman lead mines were in Spain, but Britain quickly became a major producer. Just six years after invading Britain in A.D. 49, the Romans had the lead mines in Mendip, Derbyshire, Shropshire, Yorkshire, and Wales working non-stop. By A.D. 70, Britain was producing more lead than Spain! Even though the Roman Emperor Vespasian tried to limit how much lead Britain produced, production kept growing. Lead ingots (large blocks of metal) from the late second and early third centuries have been found. We even know that British lead from Somerset was used in Pompeii, the city buried by the volcano Vesuvius in A.D. 79.

The Romans got lead from places like the Mendips, Derbyshire, Durham, and Northumberland.

To get pure lead, they used a process called smelting. They would heat the lead ore, called galena, in a special furnace. This would turn the ore into lead oxide, which then reacted with the unheated ore to create pure lead and sulfur dioxide gas.

Even though archaeologists have found remains of Roman lead smelting sites, like open hearths in the Mendips, it's been hard to fully understand how they worked because the remains are often damaged.

Getting Silver from Lead Ore

The most important reason for mining lead was to get silver. Lead and silver were often found together in a rock called galena. Galena looks like dark, heavy cubes. The Roman economy relied on silver because most of their valuable coins were made from it.

The process to get silver from lead was called cupellation, and it was quite simple. First, they would heat the ore until the lead, which contained the silver, separated from the rock. Then, they would take the lead and heat it even more, up to 1100° Celsius, using hand bellows (tools to blow air). At this high temperature, the silver would separate from the lead. The lead would turn into a substance called litharge, which was either blown away or soaked up by special bone ash containers. The litharge could then be re-heated to get the lead back. The pure silver was poured into moulds, and once cooled, it formed ingots that were sent all over the Roman Empire to be made into coins. Places like Silchester, Wroxeter, and Hengisbury Head are known for having Roman cupellation remains.

Later, in the third century A.D., when money problems hit the Roman Empire and official coins were made of bronze with just a silver coating, two fake coin factories popped up in Somerset. These factories used silver from the Mendip Hills to make coins that actually had more silver than the official ones! You can see samples of these coins and their moulds at the Museum of Somerset in Taunton Castle.

Copper Mining and Uses

Copper alloy was mainly used in Roman Britain for making things like brooches (pins), spoons, coins, small statues, and parts for armor. It was rarely used in its purest form; instead, it was mixed with other metals like tin, zinc, or lead to create different properties. Pure copper has a pinkish color, but adding other metals can change its color to pale brown, white, or yellow.

The mix of metals in copper alloys varied across the Roman Empire. For most objects, they added about 5% to 15% tin to copper to make bronze. However, mirrors needed a special silvery-white alloy called speculum, so they used bronze with about 20% tin.

Another copper alloy, brass, was harder to make and wasn't widely used until a special process called cementation was developed. In this process, zinc ore and pure copper were heated together in a sealed container. The zinc ore would turn into zinc gas, which would then mix with the copper to create brass. The Roman government controlled brass production because it was used for coins and military equipment, like parts of the lorica segmentata (Roman armor).

Gold Mining in Wales

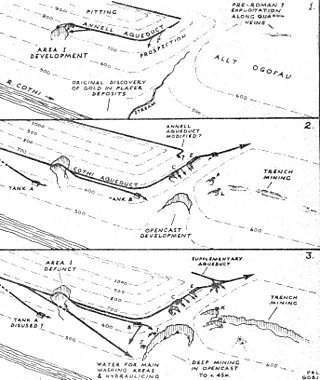

Britain's main gold mines were in Wales at Dolaucothi. The Romans found the gold veins (streaks of gold-bearing rock) there soon after their invasion. They used clever hydraulic mining methods to search the hillsides. This involved using water to wash away the top layers of soil and rock to find the gold.

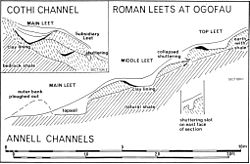

You can still see the remains of several aqueducts and water tanks above the mine today. These tanks held water for a technique called hushing. This meant releasing a huge wave of water to wash away dirt and expose the bedrock. If they found a gold vein, they would use fire-setting. This involved building a fire against the rock, then quickly cooling the hot rock with water. This sudden change in temperature would crack the rock, making it easier to break apart. Another wave of water would then wash away the broken pieces. This method created many open pits that are still visible in the hills above Pumsaint today. The Romans also built a fort, a settlement, and a bath-house nearby in the Cothi Valley.

When the open pits were no longer effective, the Romans dug long tunnels called adits into the hills at Dolaucothi. Once the gold ore was removed, it was crushed into a fine dust using heavy hammers, possibly powered by a water wheel. Then, the dust was washed in a stream of water to remove rocks and other debris. The gold dust and flakes were collected and melted into ingots (gold bars). These ingots were then sent across the Roman world to be made into coins or stored in vaults.

Iron Mining and Its Importance

Iron was one of the most important metals because it was used for armor, construction tools, farm tools, and many other building materials. There was always a need for iron, and many parts of the Roman Empire had their own iron supplies.

Roman Britain had many iron mines. The Romans built many underground mines. Once the raw iron ore was dug out, it was crushed and washed. The lighter rocks would wash away, leaving behind the heavier iron oxide. This iron oxide was then heated using a method called the bloomery method. They mixed the iron ore with charcoal and heated it in a low furnace. This process turned the ore into a spongy mass of iron called a bloom, without fully melting it. The waste material, called slag, was removed in large amounts. Archaeologists can often find old Roman iron sites by looking for these large piles of slag, which were sometimes even used to build roads! The bloom iron was then hammered and likely sold to blacksmiths for further refining and use.

Roman iron was considered very valuable because of the hard work involved in making it. A tablet found at Vindolanda (a Roman fort) shows that a man named Ascanius bought 90 Roman pounds of iron for 32 denarii (Roman coins). This shows how much iron was worth back then.

Coal: A Roman Fuel

Coal was a very important fuel for both homes and industries in Roman Britain. It provided warmth, helped with metal-working (though not for smelting iron, it was great for forging), and was used to make bricks, tiles, and pottery. We know this from archaeological finds at places like Bath (where coal was used for heating systems in homes and temples), military camps along Hadrian's Wall (where coal was dug up near the surface), forts on the Antonine Wall, lead mines in North Wales, and tile factories.

Excavations at Heronbridge, a port on the River Dee, show that the Romans had a good system for distributing coal. Coal from the East Midlands was carried along canals like the Car Dyke to places like Cambridge, where it was used in forges and for drying grain. The Romans didn't just dig coal from the surface; they also dug shafts and tunnels deep underground to follow the coal seams (layers).

Working Conditions in Roman Mines

Some miners might have been slaves, but skilled workers were definitely needed to build the aqueducts and channels that brought water to the mines. They also needed skilled people to build and operate the machinery used to remove water from the mines and to crush the ore. Large water wheels were used to lift water out of the mines, and parts of these wheels have been found in Spanish mines. A big piece of a wheel from the Rio Tinto mines can be seen in the British Museum, and a smaller piece found at Dolaucothi shows similar methods were used in Britain.

Working conditions in the mines were very tough. This was especially true when using fire-setting underground. This old mining method, used before explosives, involved building a fire against a hard rock face. Then, they would quickly pour water on the hot rock, causing it to crack from the sudden temperature change. This allowed them to extract the minerals. Writers from ancient times, like Diodorus Siculus, described this method in Egyptian gold mines. Later, Georg Agricola also wrote about it in his 16th-century book De Re Metallica. Miners tried their best to ventilate the deep mines by digging many long tunnels, which also helped drain water from the workings.

The Decline of Metal Production

The Roman economy relied heavily on the large amounts of metals mined in many regions. For example, about 100,000 tons of lead, 15,000 tons of copper, and 2,250 tons of iron were produced each year across the empire. This huge production of metal even contributed to pollution that can be seen in Greenland ice!

However, the production and availability of metals started to slow down in the late fourth century as the Roman-British economy began to struggle. People who needed metals for their jobs had to start looking for metal scraps instead. We know this from metal items found during excavations in places like Southwark and Ickham. By the end of the fourth century, Britain couldn't keep up with the demand for metals, and many metal-working sites were abandoned, leaving skilled workers without jobs.

See also

- Mining in ancient Rome

- Derbyshire lead mining history

- Dolaucothi Gold Mines

- Metal mining in Wales

- Roman engineering

- Roman technology

- Roman metallurgy

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |