Dolaucothi Gold Mines facts for kids

Roman workings at Dolaucothi mine

|

|

| Location | |

|---|---|

| County | Carmarthenshire |

| Country | Wales |

| Coordinates | 52°02′41″N 3°56′59″W / 52.0446°N 3.9498°W |

| Production | |

| Type | gold |

| Owner | |

| Company | National Trust |

| Website | http://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/dolaucothi-gold-mines |

The Dolaucothi Gold Mines are ancient Roman gold mines in Wales. They are found in the valley of the River Cothi, near a village called Pumsaint in Carmarthenshire. These mines are special because they are the only known Roman gold mines in Britain.

The mines are part of the Dolaucothi Estate, which is now looked after by the National Trust. They are also the only place to find Welsh gold outside the Dolgellau area. This site is very important for showing how clever the Romans were. It is also a Scheduled Ancient Monument, meaning it is a protected historical site.

Contents

Roman Gold Mining Methods

Experts believe people might have started looking for gold here in the Bronze Age. They probably washed gold from the river gravels. This is the simplest way to find gold.

Around AD 74, a Roman leader named Sextus Julius Frontinus came to Roman Britain. He helped control the local tribes in Roman Wales. He likely set up a fort at Pumsaint to help mine the gold at Dolaucothi.

In the 1700s, a collection of gold items was found here. These included a wheel brooch and snake bracelets. These items are now in the British Museum. In 1844, a sample of gold ore was found, proving gold was present.

The Roman fort, called Luentinum, was used from about AD 78 to 125. However, pottery found at the mines shows that mining continued until at least the late 200s AD. This means the mines were active for a long time after the Roman army left the fort.

How Romans Used Water for Mining

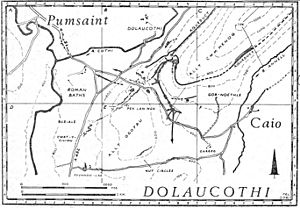

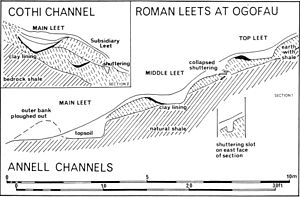

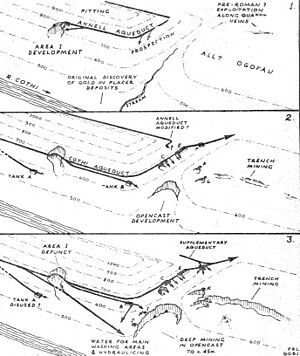

The Romans were very smart with water. They built several aqueducts and channels, called leats, to bring water to the mines. The longest one was about 7 miles (11 km) long. They used this water to find gold veins hidden under the ground.

Small streams were first used to find gold. There are still large tanks visible today that held this water. The water was released suddenly in a big wave. This wave would wash away the soil, showing the bedrock and any gold veins. This method is called hushing. It was used for centuries, even up to the 1900s in some places.

A similar method used today for mining is called hydraulic mining. The water was also used to wash crushed gold ore. It might have even powered machines to crush the ore.

One of the first aqueducts was built high up on a hill. It brought water from a small stream about 2 miles (3 km) away. There is a large tank at its end, with a big open pit below it. This shows that gold was found there. A larger aqueduct, about 7 miles (11 km) long, was built later. It crosses the same open pit, so it must have been built after the first one.

Some water tanks built by the Romans did not find gold, so they were left empty. The tank shown in the picture (Tank A) was likely used to find the edges of a gold deposit. It didn't find any, so it was abandoned.

Open-Pit Mining

The Romans were successful in finding gold. You can still see several large open pits where they dug for gold. These pits are below the large water tanks. The very last and largest tank was probably used for washing powdered ore to collect the gold dust.

More channels and tanks can be found around the edge of the very large open pit. The tank shown in the picture (Tank C) was built on the main aqueduct. It helped find a gold vein, as there is an open pit below it. This tank was likely changed later to wash crushed ore.

Most of the open pits you see today were dug by the Romans. One of the aqueducts has been proven by carbon 14 dating to be older than any modern mining work. Near the road, there is a large mound called Carreg Pumsaint. It is thought to be a pile of waste rock from the Roman mining.

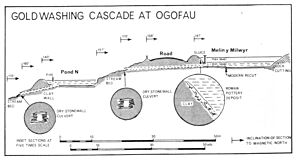

The ponds near the road from Pumsaint to Caeo were probably part of a system for washing ore. The upper pond, called Melin-y-Milwyr (soldiers' mill), contained many Roman pottery pieces from AD 78 to at least 300. This suggests that watermills might have been used here by the Romans. Or, it could have been a series of washing tables for the crushed gold ore.

Melin-y-Milwyr: The Soldiers' Mill

The pond at the start of the small road from Pumsaint to Caio was thought to be modern. But in 1970, when the water level was low, many Roman pottery pieces were found. This showed it was built by the Romans. It was connected to a smaller tank below the road by a stone channel.

The pottery found was from over 100 different pots, dating from the late 1st century AD to the end of the 4th century. Since the Roman fort at Pumsaint closed in the mid-2nd century, this means mining continued long after the soldiers left. This suggests there might be a large Roman mining village near Pumsaint that hasn't been found yet.

This water system was likely used to get the last bits of gold from the crushed ore. There were probably washing tables between the two tanks. A gentle stream of water would wash the ore, and the gold would get caught in the rough surfaces of the tables. This system was probably built around the end of the 1st century when underground mining began.

Carreg Pumsaint: The Five Saints' Stone

This site has some of the earliest proof that Romans used water-powered hammers to crush ore. The ore was probably crushed on the famous Carreg Pumsaint. This large stone block has hollows in it, made by a hammer powered by a water wheel.

As one hollow became too deep, the hammer would be moved to a new spot, creating many overlapping hollows. The hammer head must have been very big. This stone is the only one found at Dolaucothi, but similar ones exist at other Roman mines in Europe. When one side of the stone was worn out, it was simply turned to use another side.

Years later, in the Dark Ages, people found the stone and created a legend about five saints who left the marks of their heads in the stone after falling asleep.

Deep Mining: Going Underground

The Romans followed the gold veins deep underground with shafts and tunnels. Some of these tunnels still exist today. In the 1880s and 1920s, parts of Roman machines used to remove water from mines were found at the Rio Tinto mines in Spain.

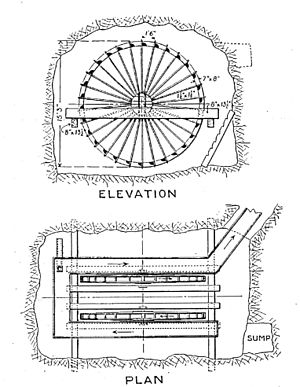

At Dolaucothi, a similar discovery was made in 1935. A piece of a water wheel was found, which is now in the National Museum of Wales. It was found with burnt wood, suggesting that fire-setting was used. This method involved heating the rock with fire and then quickly cooling it with water to make it crack.

The water wheel found at Dolaucothi was a "reverse overshot" wheel. This type of wheel was used to lift water out of the mine. A similar, larger system of 16 such wheels was found at Rio Tinto in Spain. These wheels were arranged in pairs, lifting water about 80 feet (24 meters) from the bottom of the mine.

The fragment of the water wheel at Dolaucothi was found 160 feet (49 meters) below any known entrance. This means it was part of a similar system of wheels. The gold mining at Dolaucothi was very advanced for its time. This suggests that the Roman army, with its engineering skills, was likely involved in setting up the mines.

At another part of the mine, called Penlan-wen, water was scarce. The gold vein continues for a long way there. The Romans dug a long trench to follow it. To help with air flow, especially when using fire-setting, they dug three long tunnels from the hillside. These tunnels were wider than normal to allow air to move through the trench.

Other Similar Mines

While Dolaucothi is unique in Britain for its large water systems, there are other Roman mines. These include lead mines at Charterhouse and Halkyn. Dolaucothi is most like the Roman gold mines in Transylvania (modern Romania) and in north-west Spain, like the huge site of Las Médulas.

The Romans might have used slave labour from the local area to work the mine. However, the Roman army was probably very involved, especially for their engineering skills in building aqueducts and water tanks.

Some gold was likely processed at the site, as shown by finished jewelry found there. This would have needed skilled workers, not slaves. No workshops or furnaces have been found yet, but they likely existed. Gold ingots (bars) would have been easier to transport than gold dust. Melting gold needs a very hot furnace, which the Romans knew how to build. A workshop would have been important for building and fixing mining tools.

After the Roman army left, civilian contractors might have taken over the mine.

Later History of the Mines

After the Romans left Britain in the 400s AD, the mine was abandoned for many centuries. There were attempts to restart mining in the 1800s and early 1900s, but they stopped before World War I.

In the 1930s, a shaft was dug 430 feet (131 meters) deep to find new gold veins. The mine eventually closed in 1938 because it was falling apart and flooding. It was during this time that ancient Roman underground workings were found, including the piece of the dewatering wheel. The extensive Roman remains on the surface were only fully discovered in the 1970s through careful study.

From 1975 to 2000, Cardiff University managed the underground parts of the mine. Students helped make the workings safe for visitors. They also explored for gold using drilling and other methods. Cardiff University stopped managing the mine in 2000.

It is likely that more Roman mines will be found in Britain by looking for old aqueducts and reservoirs. These structures can often be seen from the air, especially in certain lighting conditions.

Other Local Mines

The lead mines at Nantymwyn, about 8 miles (13 km) north, might also have been first worked by the Romans. This is suggested by old water tanks and aqueducts found there. These workings are high up on a mountain and are much older than the later, larger lead mine in the area.

Other Local Roman Sites

There are also Roman forts at Llandovery and Bremia near Llanio. Another fort was found in Llandeilo around 2003.

The National Trust and Dolaucothi

The National Trust has owned and managed the Dolaucothi gold mine and the Dolaucothi Estate since 1941. It was given to them by the Johnes family, who had owned the mine since the late 1500s.

University of Manchester and Cardiff University explored the site in the 1960s and 1970s. Now, Lampeter University is involved in studying the archaeology of the site. The National Trust offers guided tours for visitors, showing them the mine and the Roman history.

See also

- Aerial archaeology

- Dolaucothi Estate

- Fire-setting

- Gold mining

- Gold extraction

- Gold prospecting

- Hushing

- Mining archaeology in British Isles

- Mining in Roman Britain

- River Cothi

- Roman aqueducts

- Roman engineering

- Roman mining

- Roman technology

- Welsh gold

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |