Mining archaeology in the British Isles facts for kids

Mining archaeology is a special field that studies how people dug for metals and minerals in the past. It's like being a detective, looking for clues left behind by ancient miners. This field has grown a lot in the British Isles (like the UK and Ireland) because mining history is closely tied to the history of these places.

People like Strabo wrote about mines in the area long ago. But the first real study was done by Oliver Davies in 1935. Later, important researchers like geologist John S. Jackson (who studied Irish mines) and Lewis and Jones (who looked at the Dolaucothi gold mine in Wales) added to our knowledge. Pioneering work was also done by Ronald F. Tylecote. In the 1980s and 1990s, new scientists and enthusiasts explored many sites. These included Duncan James at the Great Orme's Head, Simon Timberlake with the Early Mines Research Group in Wales, and William O'Brien in Ireland.

Contents

Ancient Mining: The Prehistoric Period

Archaeologists have found signs of metal mining from the Bronze Age in many places across the British Isles. We know this thanks to carbon-14 analysis, which helps date ancient materials.

Early Copper and Lead Mines

Oliver Davies did a lot of research in central Wales at Cwmystwyth. He first explored it in 1935. Then, in 1986, the Early Mines Research Group revisited the Copa Hill area, including Cwmystwyth. Even though lead is common there, copper was the first metal dug up.

The main lead deposit is at "Comet lode." Here, a large open pit was dug. Inside its walls, tunnels were found that followed smaller veins of metal. A wooden "pipe" was discovered in one tunnel. Also, many old mining tools like stone hammers and lead ores were found. Charcoal samples from the site show mining happened between 2000–1900 BC and 1400 BC.

Other Important Bronze Age Sites

Two other key sites are Parys Mountain and Nantyreira mine in mid-Wales. Copper was mined early at both, even if Nantyreira mostly had lead. S. Timberlake and the Early Mines Research Group explored these in 1986. They found piles of waste rock (called "dump") at both sites. Charcoal and stone hammers were inside these piles. C14 dating shows these areas were active in the Early Bronze Age, from 2000–1500 BC.

Great Orme Copper Mine

The Great Orme mine in North Wales started in the Bronze Age and was used until the 1800s. Miners dug for copper, especially from a green mineral called malachite. The soft rock made it easy to dig, which explains why so much mining happened here.

In 1976, Duncan James found a deep shaft at Great Orme. Inside, there were signs of "firesetting" (heating rock to crack it), stone hammers, bone tools, and waste rock. Radiocarbon dating showed this activity happened between 1395–935 BC. Andy Lewis continued this research in the late 1980s. It's thought that mining here stopped around 1000 BC.

Miners used open pits on the surface and underground tunnels. The underground tunnels had many openings, which also helped with air flow. Tools found here include pointed bone tools and stone hammers. Other tools like stone mortars and pestles show how ores were processed. Giant hammers, unique for the British Isles, were also found.

Alderley Edge and Irish Mines

Early mining was also found at Alderley Edge. However, much of the ancient evidence was destroyed by large-scale mining in the 1800s.

Ireland also has many ancient mining sites. The two most important are Mount Gabriel and Ross Island mines.

Ross Island is near Killarney. Archaeologists found two ancient mines there. William O'Brien explored the "Danish mines" and found a mine cave and a large pile of waste rock. Another unknown mine appeared after digging. He also found pits in the bedrock that were likely ancient. What makes Ross Island special is finding a Beaker settlement (an ancient village) very close to the mining areas. This settlement had metalworking pits, hammers, and rock waste. These finds, along with early dates around 2400 BC, make Ross Island very important for mining archaeology.

Mount Gabriel, near west Cork, shows how copper was mined in the Early Bronze Age, around 1700 BC. Researchers found 32 areas where mining took place. Shallow pits and large piles of waste rock with charcoal and tools are proof of Bronze Age copper mining. Mount Gabriel is one of the few places where ancient mining sites were not disturbed by later mining in the 1800s. This is because the copper veins there were not very rich.

Iron Age Mining

When the Iron Age began around 700 BC, mining spread across the British Isles. A good example from this time is Puzzlewood's surface mines. This site became very busy during the Roman and late Middle Ages. Miners dug for limonite ores, which are a type of iron ore. The ancient mining remains here are open pits called Scowles Holes. It's also important that homes from 100–400 AD were found very close to these mines.

Roman Mining: The Roman Period

During the Roman period, a lot of mining happened in the Mendips and at Dolaucothi. Large blocks of lead (called "pigs") from the Peak District in Derbyshire have been found, but we don't know exactly where those mines were.

Mendip Mines

It's possible that the Mendip mines were used even in the Late Bronze Age. Some earthworks might be from the British Iron Age. But mining really took off during the Roman era. We don't have many direct clues about the mines themselves. However, we know that the Charterhouse Roman Town was protected by a fort. Similar protection might have been at the Green mines for a time.

Dolaucothi Gold Mines

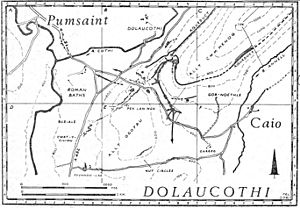

The most famous Roman mining site is the Dolaucothi Gold Mines near Pumpsaint in Wales. Jones and Lewis explored these gold mines in 1969. The mines were used for a very long time, and you can see signs of digging both above and below ground. The Romans were here for about 300 years, starting when they first arrived in Britain.

Signs of mining before the 1800s are found in five main areas: Ogofau, Niagara, Allt Cwmhenog, Pen-lan-wen, and Cwrt-y-Cillion. In the Ogofau area, many pits were found. Even with later digging and waste piles, the Roman open pits are still clear. The main one is at least 24 meters deep. Two other open pits, called the "Roman pit" and the "Mitchell pit," are also from this time.

Another possible Roman mining area is Pen-lan-wen, where a group of tunnels (called adits) was found. You can see marks from chisels and picks on the tunnel walls, but the evidence is not very strong.

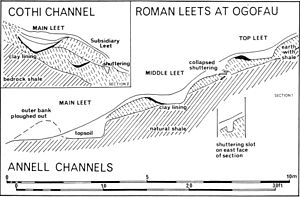

The most amazing thing at Dolaucothi is the structures built for "hushing". Hushing was a Roman mining method where large amounts of water were suddenly released to wash away soil and expose gold veins. Through excavations, Lewis and Jones found four main water channels (called leats), and a complex system of tanks and reservoirs. These were either right next to the mines or near water sources. Another important discovery was a piece of a "drainage wheel." This suggests there was an underground wheel system, much like the famous one at Rio Tinto in Spain, used to remove water from the mines.

Medieval Mining: The Middle Ages

The Middle Ages was a busy time for metal mining. Monasteries often played a big part in digging for minerals. A famous site from this period is the northern Pennines at Brownhill, Cumbria. Here, lead ores were dug from silver-rich veins. The mine was controlled by the King or Queen.

Miners got lead ores from open pits that were shaped like half-eggs, so they were called "bell-pits." Signs of medieval mining are also found at Copa Hill, where small parts of a water channel system were discovered. Further digs at Ross Island showed a place where metal was melted (a smelting site) connected to a nearby village. However, any actual mining from that time is hard to find now. For tin mining, "lode back pits" at Godolphin have been identified as medieval.

How Other Fields Help Mining Archaeology

To truly understand ancient mines, we need to look at more than just the old buildings and tunnels. We also need to think about the "social context." This includes things like:

- Who were the miners?

- How did they live?

- How did they get along with nearby communities?

- What was the special meaning of the metal they dug up?

- How was that meaning shown in the finished objects?

Basically, we try to imagine the past society where mining happened.

Working with experimental archaeology is also very helpful. This is where scientists try to recreate old mining methods. This helps us understand how ancient tools were used and what marks they left behind.

Also, scientific tests can tell us about the chemical makeup of minerals, waste (slag), and old objects. This helps archaeologists connect different sites or figure out where materials came from. Geology and pollen analysis can even show us what the landscape looked like in different eras. Finally, old documents and writings are very useful for understanding mining in historical times.

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |