De re metallica facts for kids

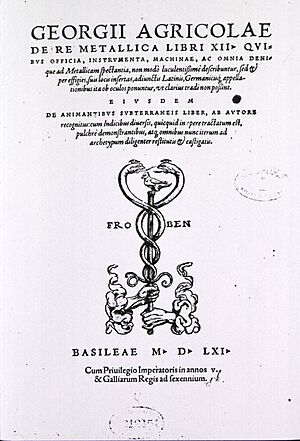

Title page of 1561 edition

|

|

| Author | Georgius Agricola |

|---|---|

| Translator | Herbert Hoover Lou Henry Hoover |

|

Publication date

|

1556 |

|

Published in English

|

1912 |

| ISBN | 0-486-60006-8 |

| OCLC | 34181557 |

De re metallica is a famous book from 1556. Its name is Latin for On the Nature of Metals or Minerals. This book was like a super detailed guide to everything about mining, refining, and smelting metals. It was written by Georg Bauer, who used the Latin pen name Georgius Agricola. (Both "Bauer" and "Agricola" mean "farmer" in German and Latin!)

The book was published a year after Agricola passed away. This was because it took a long time to create all the amazing woodcut pictures for the text. For 180 years after it came out, De re metallica was the most important book about mining. It was also a key book for chemistry at the time.

Before this book, mining knowledge was often kept secret. It was passed down by word of mouth among a small group of experts. These experts were like the master builders of huge cathedrals. They didn't share their secrets with just anyone. But during the Renaissance, things started to change. With better travel and the invention of the printing press, knowledge could spread much faster. In 1500, the first printed book about mining came out. But the most important work was De Re Metallica by Georgius Agricola.

Agricola spent nine years in a mining town called Joachimsthal (now in the Czech Republic). Later, he lived in Chemnitz in Saxony, another big mining area.

Contents

- Why This Book Was So Important

- The Hoover Translation

- What's Inside the Book?

- Book 1: Why Mining is Good

- Book 2: Finding Metal Veins

- Book 3: Types of Veins

- Book 4: Mining Rules and Officials

- Book 5: Digging for Ore

- Book 6: Mining Tools and Machines

- Book 7: Testing Ore (Assaying)

- Book 8: Preparing Ore for Smelting

- Book 9: Smelting Metals

- Book 10: Separating Gold and Silver

- Book 11: Separating Silver from Copper

- Book 12: Making Other Useful Materials

- Publication History

- Different Editions of the Book

- See also

Why This Book Was So Important

De Re Metallica was incredibly influential. For over a hundred years, it was the main textbook used across Europe. The German mining methods it showed were the most advanced back then. Many other European countries were jealous of the metal wealth from German mines.

The book was printed in Latin, German, and Italian. Being in Latin meant that any educated person in Europe could read it. The book had 292 fantastic woodcut illustrations. These detailed pictures showed machines and processes. This made it a very practical guide for anyone wanting to use the latest mining technology.

The original drawings for the woodcuts were made by an artist named Blasius Weffring. Then, skilled craftsmen prepared the woodcuts for printing.

The Hoover Translation

In 1912, the first English translation of De Re Metallica was published. It was translated by a married couple: Herbert Hoover and Lou Henry Hoover. Herbert Hoover was a mining engineer who later became a President of the United States. Lou Henry Hoover was a geologist and knew Latin very well.

Their translation is famous for being clear and easy to understand. It also had many helpful notes. These notes explained old references to mining and metals. Later translations into other languages often used the Hoovers' notes. This was because Agricola had invented hundreds of new Latin words for mining terms that didn't exist in old Latin! The Hoovers' notes helped explain these tricky words.

What's Inside the Book?

The book has a preface (an introduction) and twelve chapters, called "books." Each book covers a different topic. It also has many woodcuts. These pictures show diagrams of the equipment and processes.

Book 1: Why Mining is Good

This part of the book talks about arguments against mining and Agricola's answers. Some people thought mining was bad because it was dangerous or ruined the land. Agricola argued that metals are essential for building and farming. He also said that most mining accidents happen because of carelessness. He believed mining was an honorable and profitable job. He also said that a good miner needs to know about many subjects, like philosophy, medicine, astronomy, surveying, arithmetic, architecture, drawing and law.

Book 2: Finding Metal Veins

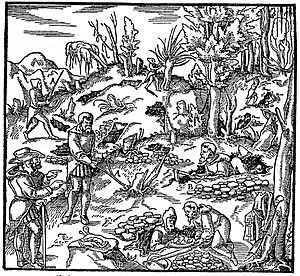

This book explains how to find metal veins. Agricola suggests that mine owners should live near their mines. He also advises investing in both new and old mines to balance risks. He describes where miners should look for metals, usually in mountains with wood for fuel and plenty of water. He talks about searching streams for metals that have washed down. He also mentions looking for veins that show on the surface. Agricola even describes dowsing (using a forked stick to find water or minerals), but he didn't believe it worked himself!

Book 3: Types of Veins

This book describes the different kinds of metal veins found in rocks. It has 30 illustrations showing these veins. Agricola also talks about using a compass to find the direction of veins. He explains that gold found in streams comes from veins that water has broken apart.

Book 4: Mining Rules and Officials

This book explains how mining areas are managed. An official called the Bergmeister (mine master) was in charge. He would mark out areas for mining when a new vein was found. This book also covers mining laws. It explains how mines could be divided into shares for owners. It also lists the jobs of different officials who regulated mines and collected taxes on the metal produced.

Book 5: Digging for Ore

This book describes how to dig for ore underground. When a vein is found, a shaft is dug, and a wooden shed with a windlass (a machine for lifting) is placed over it. Tunnels are dug to follow the vein. Agricola explains that gold, silver, copper, and mercury can be found as pure metals. He also describes how to tell if metal ores are present by looking at different minerals and colors of earth. The way miners dig depends on how hard the rock is. Soft rock can be dug with a pick, while hard rock might need fire to break it. He also talks about dangerous gases and water flooding mines. The book ends with a detailed section on surveying, which helps miners follow veins and avoid digging into other mines.

Book 6: Mining Tools and Machines

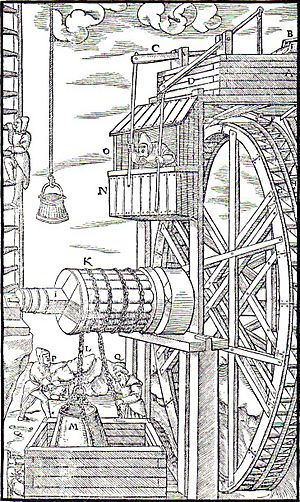

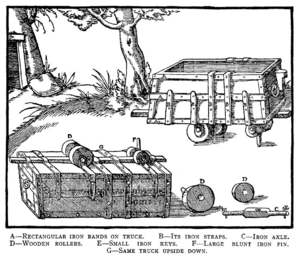

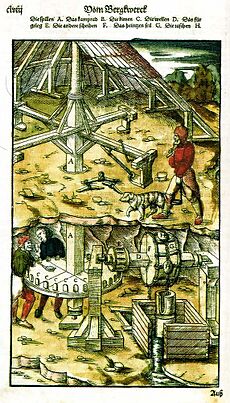

This book is full of illustrations showing all the tools and machines used in mining. It describes hand tools, different kinds of buckets, and wheelbarrows. It also shows early minecarts on wooden tracks. Agricola details various machines for lifting heavy weights. Some were powered by people, some by up to four horses, and some by waterwheels. He also describes machines that used chains of buckets or piston pumps to lift water out of mines. Because pumps could only lift water a certain height, many pumps were needed for deep mines. The book also shows designs for ventilating shafts with wind scoops or fans.

Book 7: Testing Ore (Assaying)

This book explains how to test ore to see how much metal it contains. This process is called assaying. Agricola describes different types of furnaces and tools like crucibles. He explains how to prepare the ore and add other substances (called fluxes) to help the metal melt. He details how to separate gold and silver from other metals using a process called cupellation. He also describes how to separate gold using mercury. The book includes math examples to show how to calculate the amount of metal from the test.

Book 8: Preparing Ore for Smelting

In this book, Agricola describes how to prepare ores before they are melted down. This includes sorting the ore, roasting it (heating it to remove impurities), and crushing it. He talks a lot about using water to wash ores, explaining different methods and machines for crushing and washing.

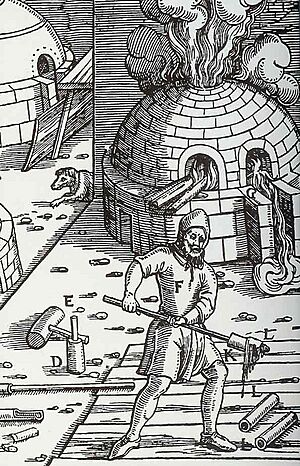

Book 9: Smelting Metals

This book describes smelting, which is melting ore to get pure metal. Agricola explains how to design furnaces. These furnaces were usually made of brick or stone with bellows (to blow air) at the back. Molten metal would collect in a pit at the front. He describes how to load the furnace with ore and charcoal. For gold and silver, a lot of waste material (slag) was produced. The book also covers making crucible steel and distilling mercury and bismuth.

Book 10: Separating Gold and Silver

This book explains how to separate silver from gold using acids. He also describes other methods, including using mercury to separate gold. It also covers large-scale cupellation, a process to separate precious metals from lead.

Book 11: Separating Silver from Copper

This book describes how to separate silver from copper or iron. This is done by adding a lot of lead at a certain temperature. The lead mixes with the silver and separates from the copper. This process might need to be repeated several times. Then, the lead and silver can be separated using cupellation.

Book 12: Making Other Useful Materials

This book describes how to make other important materials that Agricola called "juices." These include salt, soda, alum, vitriol, sulphur, and bitumen. Finally, it covers glass making. Agricola seemed less sure about making glass from scratch but was clearer about melting glass to make objects.

Publication History

Even though Agricola died in 1555, the book's publication was delayed until 1556. This was because of the time it took to finish all the detailed woodcut illustrations.

A German translation was published in 1557. A second Latin edition came out in 1561. A Spanish version, which was more than just a translation, was made in 1569. This was later translated into French in 1743.

The famous English translation by Herbert Hoover and Lou Henry Hoover was published in London in 1912. This edition was very high quality, with fine paper and binding, trying to match the original 16th-century book. Because of this, copies of the 1912 edition are now rare and valuable. Luckily, the translation has been reprinted by Dover Books.

The Hoovers' translation was very important. Their detailed footnotes helped later translators in other languages. This was especially true because Agricola had invented many new Latin words for mining terms that didn't exist in classical Latin.

Different Editions of the Book

- Agricola, Georg. De re metallica. 1st ed. Basil: Hieronymus Froben & Nicolaus Episcopius, 1556.

- Agricola, Georg. De re metallica. 2nd ed. Basil: Hieronymus Froben & Nicolaus Episcopius, 1561.

- Agricola, Georg. De re metallica. Basil: Ludwig König, 1621.

- Agricola, Georg. De Re Metallica. Basil: Emanuel König, 1657.

- Agricola, Georg. Vom Bergkwerck. Translated by Philipp Bech. Basel: Hieronymus Froben & Nicolaus Episcopius, 1557.

- Agricola, Georg. Bergwerck Buch. Translated by Philipp Bech. Basil: Ludwig König, 1621.

- Agricola, Georg. Zwölf Bücher vom Berg- und Hüttenwesen. Edited by Carl Schiffner and others. Translated by Carl Schiffner. Berlin: VDI-Verlag, 1928.

- Agricola, Georg. Opera di Giorgio Agricola de L’Arte de Metalli. Basil: Hieronymus Froben & Nicolaus Episcopius, 1563.

- Agricola, Georg. De Re Metallica. Translated by Herbert Clark Hoover and Lou Henry Hoover. 1st English ed. London: The Mining Magazine, 1912.

- Agricola, Georg. De Re Metallica. Translated by Herbert Clark Hoover and Lou Henry Hoover. New York: Dover Publications, 1950. Reprint of the 1912 edition.

- Agricola, Georg. De Re Metallica. Translated by Herbert Clark Hoover and Lou Henry Hoover. New York: Dover Publications, 1986. Reprint of the 1950 reprint of the 1912 edition.

See also

- De la pirotechnia

- Naturalis Historia

- Pliny the Elder

- Scientific literature

- Theophrastus