Theophrastus facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Theophrastus

|

|

|---|---|

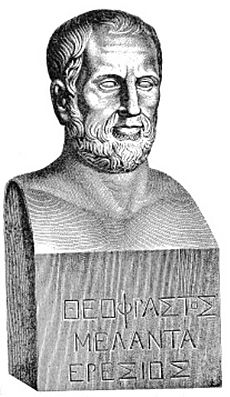

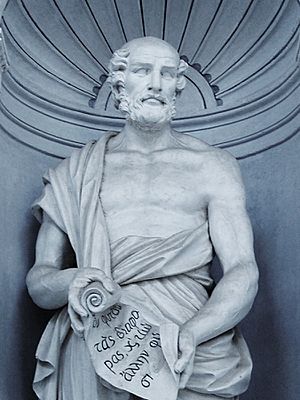

Statue of Theophrastus, Palermo Botanical Garden

|

|

| Born | c. 371 BC Eresos

|

| Died | c. 287 BC (aged 83 or 84) |

| Era | Ancient philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Peripatetic school |

|

Main interests

|

|

|

Notable ideas

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

Theophrastus (/θiːəˈfræstəs/; Greek: Θεόφραστος Theόphrastos; around 371 – 287 BC) was a famous Greek thinker. He followed Aristotle as the leader of the Peripatetic school, a group of philosophers.

Theophrastus was born in Eresos on the island of Lesbos. His real name was Tyrtamus. But his teacher, Aristotle, gave him the nickname "Theophrastus," which means "godly phrased." This was because of his amazing way with words.

He moved to Athens when he was young and first studied at Plato's school. After Plato died, he joined Aristotle. When Aristotle had to leave Athens, Theophrastus became the head of the Lyceum. He led the Peripatetic school for 36 years, and it grew a lot under his care.

Theophrastus is often called the "father of botany" because of his important books about plants. After he died, the people of Athens honored him with a public funeral. His student, Strato of Lampsacus, took over the school after him.

Theophrastus was interested in many subjects. These included biology, physics, ethics (how to live well), and metaphysics (the nature of reality). His two main books about plants, Enquiry into Plants and On the Causes of Plants, greatly influenced science during the Renaissance. Other works that still exist include On Moral Characters, On Sense Perception, and On Stones. He also wrote about grammar and logic.

Contents

His Life Story

Most of what we know about Theophrastus comes from a book called Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers. This book was written more than 400 years after Theophrastus lived.

He was born in Eresos on the island of Lesbos. His birth name was Tyrtamus. But he became known as "Theophrastus" because of his graceful way of speaking. His teacher, Aristotle, supposedly gave him this nickname.

After studying philosophy in Lesbos, he moved to Athens. There, he might have studied with Plato. He became good friends with Aristotle. When Plato died (around 348/7 BC), Theophrastus may have joined Aristotle when he left Athens.

It seems that Aristotle and Theophrastus began their studies of natural science on Lesbos. Aristotle focused on animals, while Theophrastus studied plants. Theophrastus likely went with Aristotle to Macedon when Aristotle became a teacher to Alexander the Great around 343/2 BC.

Around 335 BC, Theophrastus moved with Aristotle back to Athens. There, Aristotle began teaching at the Lyceum. After Alexander the Great died, people in Athens became angry at those connected to Macedon. This forced Aristotle to leave Athens. Theophrastus stayed behind and became the head (scholarch) of the Peripatetic school. He kept this role even after Aristotle died in 322/1 BC.

Aristotle named Theophrastus as the guardian of his children, including Nicomachus. Aristotle also left his library and original writings to Theophrastus. He also chose Theophrastus to lead the Lyceum after him.

Theophrastus led the Peripatetic school for 35 years. He died at the age of 85, according to Diogenes. He is said to have once remarked, "We die just when we are beginning to live."

Under his leadership, the school grew very strong. Diogenes says there were more than 2,000 students at one point. When Theophrastus died, he left his garden, house, and buildings to the school. This made it a permanent place for teaching. The famous comedy writer Menander was one of his students.

His popularity was clear from the respect he received from powerful rulers like Philip, Cassander, and Ptolemy. He was even accused of not respecting the gods, but the charge failed completely. He was given a public funeral, and "the whole population of Athens, honoring him greatly, followed him to the grave." Strato of Lampsacus became the next head of the Lyceum.

His Writings

Lists from Diogenes show that Theophrastus wrote 227 books. This means he wrote about almost every subject known at the time. His writings were likely similar to Aristotle's, but with more details. Like Aristotle, most of his writings are now lost works.

He wrote about logic, including books on Topics and Analysis of Syllogisms. He also wrote about Natural Philosophy, Heaven, and Meteorological Phenomena (things happening in the sky).

Theophrastus also wrote about Warm and Cold, Water, Fire, and the Sea. He wrote about how things freeze and melt. He also explored topics like the Soul and Sense Perception.

He wrote about early Greek philosophers like Anaximenes and Democritus. He also wrote about Plato's political ideas.

He studied history, and his work was used by later writers like Plutarch. But his main focus was continuing Aristotle's work in natural history. This is shown by his books On Stones, Enquiry into Plants, and On the Causes of Plants, which we still have today.

In politics, he followed Aristotle's ideas. He wrote books on the State, Education, Royalty, and the Best State. He also wrote about Laws, which described the laws of different Greek and non-Greek states. This book was meant to go along with Aristotle's Politics. He also wrote about public speaking and poetry.

Theophrastus likely had different ideas from Aristotle in his writings on ethics and metaphysics. Especially when it came to motion, the soul, and God.

Many of his surviving works are only in pieces. His translator, Arthur F. Hort, noted that the style of these works suggests they were notes for lectures. They are not easy to read and can sometimes be unclear.

On Plants

His most important books are two large works on plants: Enquiry into Plants (also known as Historia Plantarum) and On the Causes of Plants. These books were the most important writings on plants in ancient times and the Middle Ages. They were the first to organize the plant world into a system. Because of these works, some people, like Carl Linnaeus, call him the "father of botany".

The Enquiry into Plants originally had ten books, and nine of them still exist. This work classifies plants based on how they grow, where they live, their size, and how they are used (like for food, juices, or herbs).

- The first book talks about the parts of plants.

- The second book discusses how plants reproduce and when to plant seeds.

- Books three, four, and five are about trees, their types, where they grow, and their uses.

- The sixth book covers shrubs and spiny plants.

- The seventh book is about herbs.

- The eighth book describes plants that produce edible seeds.

- The ninth book talks about plants that produce useful juices, gums, and resins.

On the Causes of Plants originally had eight books, and six of them still exist. It discusses how plants grow and what affects how many fruits they produce. It also covers the best times to plant and harvest, how to prepare the soil, and how to use tools. The book also describes the smells, tastes, and properties of many plants. This work mainly focuses on how plants are used for economic purposes, rather than for medicine, though medicine is sometimes mentioned.

Even though these books contain some strange or made-up stories, they also have valuable observations about how plants work. Theophrastus studied how seeds sprout and understood how important climate is for plants.

On Moral Characters

His book Characters (Ἠθικοὶ χαρακτῆρες) describes thirty short types of moral behavior. These are the first known attempts to write systematic character descriptions. Some people think this book was a standalone work. Others believe Theophrastus wrote these sketches over time, and they were collected after he died. The Characters has inspired many writers, including Joseph Hall and Jean de La Bruyère.

On Sensation

A book called On Sense Perception (Περὶ αἰσθήσεων) is important for understanding what ancient Greek philosophers thought about how we sense things. Later, in the sixth century, Priscian of Lydia wrote a commentary on this work. Other fragments related to this topic include writings on Smells, Fatigue, Dizziness, Sweat, Swooning, Palsy, and Honey.

Physics

Parts of a History of Physics (Περὶ φυσικῶν ἱστοριῶν) still exist. This includes sections on Fire, Winds, and signs of Waters, Winds, and Storms.

Metaphysics

The Metaphysics (also called On First Principles), has nine chapters. It was once thought to be just a part of a larger work. But now, many scholars believe it is a complete book.

On Stones

In his book On Stones (Περὶ λίθων), Theophrastus classified rocks and gems. He grouped them by how they behaved when heated and by common properties. For example, he grouped amber and magnetite together because both can attract things. This book was an important source for other books about stones until the Renaissance.

Theophrastus describes different types of marble. He mentions coal, which he says metal-workers used for heating. He also describes various metal ores. He knew that pumice stones came from volcanoes. He also wrote about precious stones like emeralds, amethysts, onyx, and jasper. He described a "sapphire" that was blue with gold veins, which was likely lapis lazuli.

He knew that pearls came from shellfish and that coral came from India. He also talked about the fossilized remains of living things. He discussed the practical uses of different stones. For example, minerals needed to make glass, pigments for paint like ochre, and materials for plaster.

Many rare minerals were found in mines. Theophrastus mentions the famous copper mines of Cyprus. He also talks about the even more famous silver mines, probably those at Laurium near Athens. These mines were the basis of Athens' wealth. Theophrastus wrote a separate book On Mining, but it is now lost.

Pliny the Elder clearly used On Stones for his own book, Naturalis Historia, written in 77 AD. Pliny added new information about minerals. Theophrastus's work is more organized and has fewer myths compared to other writings of his time.

His Philosophy

It's hard to know exactly how much Theophrastus agreed with Aristotle. This is because so many of his writings are lost. We have to piece together his ideas from what later writers like Alexander of Aphrodisias and Simplicius said about him.

Logic

Theophrastus continued to build on the grammatical basis of logic and rhetoric. In his book on the parts of speech, he separated main parts from smaller ones. He also looked at direct words versus metaphorical ones. He discussed the feelings (pathe) expressed in speech.

He wrote a lot about the unity of judgment and different types of negation. He also discussed the difference between things that are always true and things that are true under certain conditions. In his ideas about syllogisms, he showed how to convert universal affirmative judgments. He had some differences from Aristotle in how he set up and proved syllogisms.

Physics and Metaphysics

Theophrastus began his Physics by showing that all natural things need principles. Most importantly, they need motion as the basis for all change. He disagreed with Aristotle about space. He thought space was just the way bodies are arranged and positioned. He called time an accident of motion.

He had different ideas from Aristotle about motion. He thought motion applied to all categories, not just the ones Aristotle listed. He saw motion as something natural to the universe and the sky.

He believed that nothing could be active without motion. So, he thought all activities of the soul were related to motion. Desires and emotions were linked to body motion. Thinking and contemplation were linked to spiritual motion. The idea of a spirit completely separate from the body seemed doubtful to him. Other Peripatetic philosophers, like Strato, further developed these ideas.

Theophrastus often preferred to explore the difficulties of a problem rather than solve them. This is clear in his Metaphysics. He did not always try to find the deepest reasons for things, as Aristotle did. In ancient times, people complained that Theophrastus was not clear about God. He sometimes described God as Heaven, and other times as a life-giving breath (pneuma).

Ethics

Theophrastus did not believe that happiness came only from being virtuous. He thought that happiness also depended on outside influences. He believed that moral rules could sometimes be less important if it helped a friend. Later, people criticized his saying in the Callisthenes: "life is ruled by fortune, not wisdom."

He also had different ideas about pleasure than Aristotle. He preferred a life of thinking (theoretical) over an active (practical) life. But he thought the practical life should be free from family duties, which Aristotle would not have liked.

Theophrastus was against eating meat. He believed it was wrong because it took away the lives of animals. He argued that non-human animals can reason, sense, and feel just like humans do.

Works

- Historia plantarum, 1549.

- [Opere], 1613.

- Metaphysics (or On First Principles).

- Enquiry into Plants: Books 1–5. Translated by A. F. Hort, 1916.

- Enquiry into Plants: Books 6–9; Treatise on Odours; Concerning Weather Signs. Translated by A. F. Hort, 1926.

- De Causis Plantarum. Translated by B. Einarson and G. Link, 1989–1990.

- On Characters.

- On Sweat, On Dizziness and On Fatigue. Translated by W. Fortenbaugh, R. Sharples, M. Sollenberger. Brill 2002.

- On Weather Signs.

- On Stones

Modern editions

- Theophrastus' Characters: An Ancient Take on Bad Behavior by James Romm (author), Pamela Mensch (translator), and André Carrilho (illustrator), Callaway Arts & Entertainment, 2018.

Brill

The International Theophrastus Project started by Brill Publishers in 1992. This project aims to collect and translate all sources about Theophrastus.

- 1. Theophrastus of Eresus: Sources for His Life, Writings, Thought and Influence (two volumes), edited by William Fortenbaugh et al., Leiden: Brill, 1992.

- 1.1. Life, Writings, Various Reports, Logic, Physics, Metaphysics, Theology, Mathematics [Texts 1–264].

- 1.2. Psychology, Human Physiology, Living Creatures, Botany, Ethics, Religion, Politics, Rhetoric and Poetics, Music, Miscellanea [Texts 265–741].

- Other volumes in the series include:

- 1. Theophrastus of Eresus: Sources for His Life, Writings, Thought and Influence — Commentary, Leiden: Brill, 1994

- 2. Logic [Texts 68–136], by Pamela Huby (2007).

- 3.1. Sources on Physics (Texts 137–223), by R. W. Sharples (1998).

- 4. Psychology (Texts 265–327), by Pamela Huby (1999).

- 5. Sources on Biology (Human Physiology, Living Creatures, Botany: Texts 328–435), by R. W. Sharples (1994).

- 6.1. Sources on Ethics [Texts 436–579B], by William W. Fortenbaugh (2011).

- 8. Sources on Rhetoric and Poetics (Texts 666–713), by William W. Fortenbaugh (2005).

- 9.1. Sources On Music (Texts 714-726C), by Massimo Raffa (2018).

- 9.2. Sources on Discoveries and Beginnings, Proverbs et al. (Texts 727–741), by William W. Fortenbaugh (2014).

Images for kids

-

Aristotle, Theophrastus, and Strato of Lampsacus. Part of a fresco in the portico of the University of Athens painted by Carl Rahl, c. 1888.

-

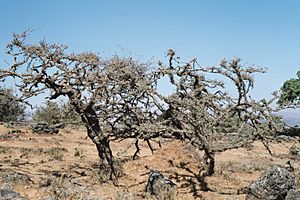

Frankincense trees in Dhufar

-

Cinnamomum verum, from Köhler's Medicinal Plants, (1887)

-

Cut emeralds

See also

In Spanish: Teofrasto para niños

In Spanish: Teofrasto para niños

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |