Movable type facts for kids

Movable type is a clever way of printing that uses small, separate pieces to make words and sentences. Imagine tiny blocks, each with a letter or a symbol on it. You can arrange these blocks to form any text you want, then use them to print on paper. This invention changed how books and information were shared around the world!

Contents

How Movable Type Works

The first movable type for paper books was invented in China around 1040 AD by a person named Bi Sheng. He used pieces made of porcelain, a type of ceramic. Later, in 1161, China also used movable metal type to print special codes on paper money to prevent fakes. The oldest book still existing today that was printed with movable metal type is called Jikji. It was printed in Korea in 1377.

Movable type systems didn't spread much beyond East Asia at first. But some ideas about this technology might have reached Europe through travelers.

Around 1450, a German goldsmith named Johannes Gutenberg invented a metal movable-type printing press. He also found a new way to make the type pieces using a special mold. Gutenberg was the first to use an alloy (a mix of metals) of lead, tin, and antimony for his type. This mix worked so well that it was used for over 550 years!

For languages that use an alphabet (like English), setting up pages with movable type was much faster than carving entire pages into wooden blocks. The metal type pieces lasted longer, and the letters looked more uniform and neat. The famous Gutenberg Bible, printed in 1455, showed how good movable type was. Because of this, printing presses quickly spread across Europe and then around the world. Many people think the printing press was a key invention that helped start the Renaissance, a time of great learning and art.

Later, in the 1800s, new machines called "hot metal typesetting" took over, and movable type became less common in the 1900s.

Early Printing Ideas

Before movable type, people used other methods to make copies of symbols or texts.

Seals and Stamps

Long ago, around 3000 BC in ancient Sumer (now Iraq), people used hard metal punches to imprint symbols. These were like early versions of letter punches. They also used cylinder seals in Mesopotamia, rolling them over wet clay to create patterns.

Seals and stamps might have been early steps toward movable type. Some old brick stamps from Mesopotamia, dating back to 2000 BC, show uneven spacing. This makes some experts wonder if they were made using separate, movable pieces. Even the mysterious Phaistos Disc from ancient Crete (around 1800-1600 BC) might have been made by pressing pre-made "seals" into soft clay.

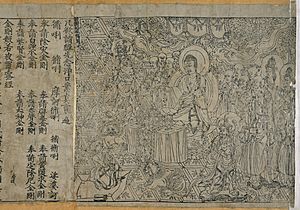

Woodblock Printing

Before paper, people wrote on bones, shells, bamboo, metal, stone, or silk. But when paper was invented in China during the Han dynasty, writing became easier and cheaper. Still, copying books by hand took a lot of work.

Around the 8th century, in China's Tang dynasty, woodblock printing was invented. Here's how it worked:

- First, a handwritten text was glued onto a smooth wooden board. The paper was so thin you could see the letters through it, but backward.

- Then, skilled carvers cut away all the wood around the letters, leaving the characters raised (in relief).

- To print, ink was spread on the raised characters, and paper was placed on top. Workers gently rubbed the back of the paper, and the characters would print.

Woodblock printing was very important for sharing culture, especially during the Song dynasty. However, it had problems: carving each printing plate took a lot of time, effort, and wood. It was also hard to store all the plates, and fixing mistakes was difficult.

History of Movable Type

Ceramic Movable Type

Bi Sheng (990–1051) developed the first known movable-type system in China around 1040 AD, during the Northern Song dynasty. He used ceramic materials. A Chinese scholar named Shen Kuo described Bi Sheng's method:

When Bi Sheng wanted to print, he put an iron frame on an iron plate. He placed the ceramic type pieces close together inside the frame. Once the frame was full, it became one solid block of type. He would warm it near a fire to melt the paste holding the types. Then, he pressed a smooth board over the surface to make sure all the types were perfectly even.

For common characters, he had many copies (sometimes twenty or more!) so he could print them multiple times on the same page. When the characters weren't being used, he organized them with paper labels in wooden cases.

This method wasn't easy for printing just a few copies. But for hundreds or thousands of copies, it was incredibly fast! He often worked on two forms at once: while one was printing, he was setting up the next. This way, printing was very quick.

Some people thought Bi Sheng's clay types were too "fragile," but later tests showed they were actually very strong after being baked. They were as hard as horn and wouldn't break even if dropped from a height.

Wooden Movable Type

Bi Sheng also tried using wooden movable type around 1040 AD. However, this wasn't as successful as ceramic type because wood grains could cause problems, and the wood pieces could become uneven after soaking up ink.

In 1298, Wang Zhen, a Chinese official, re-invented a way to make wooden movable types. He made over 30,000 wooden types and printed 100 copies of a book with more than 60,000 Chinese characters. He even wrote a book about his invention! Wooden types were more durable than clay, but they still wore down after repeated printing.

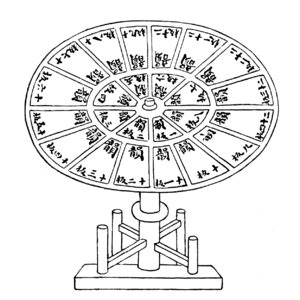

Wang Zhen improved the system by using two spinning circular tables to hold his type pieces. One table had 24 sections for types based on rhyming patterns, and the other held other characters. This made it easier to find and arrange the types.

Wooden movable types continued to be used in China. As late as 1733, a huge 2300-volume encyclopedia was printed using over 250,000 wooden movable types!

Metal Movable Type

China

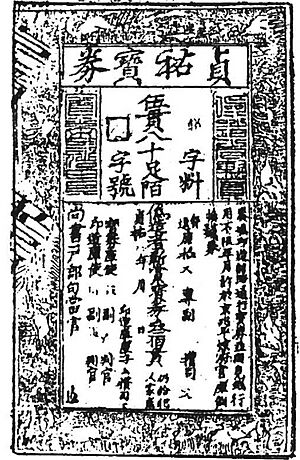

Evidence shows that bronze movable type printing was invented in China by the 1100s. China used large bronze plates to print paper money and official documents. These documents often had small bronze metal types embedded in them as anti-counterfeit markers. For example, some old paper money had two square holes where special bronze characters were inserted. Each note had a different combination of these characters to make it harder to copy.

Later, during the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), Wang Zhen also mentioned using tin movable type, but it didn't work well with the ink. However, by the late 1400s, bronze type was widely used in Chinese printing.

During the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), a person named Hua Sui used bronze type to print books in 1490. In 1574, a massive 1000-volume encyclopedia was printed with bronze movable type.

In 1725, the Qing dynasty government made 250,000 bronze movable-type characters! They used them to print 64 sets of a huge encyclopedia, with each set having over 5,000 volumes. That's a lot of printing!

Korea

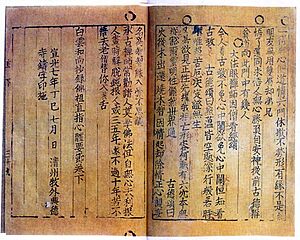

In 1234, the first books known to be printed with metal type were published in Goryeo dynasty Korea. While those specific books are gone, the oldest existing book printed with metal movable type in the world is the Jikji, printed in Korea in 1377.

Korean scholars used techniques for bronze casting, which they already used for making coins and statues, to create metal type. A scholar named Seong Hyeon described the process: First, they carved letters into beech wood. Then, they pressed these wooden letters into fine sandy clay to create negative molds. Molten bronze was poured into these molds, and when it cooled, it formed the metal type pieces. Finally, they cleaned up the pieces and arranged them for printing.

In the early 1400s, a generation before Gutenberg, King Sejong the Great created a simpler alphabet called hangul for common people. This could have made typecasting and printing much easier. However, the educated elite in Korea didn't want to lose hanja (Chinese characters), which they saw as a sign of their status. This, along with rules against selling printed books, limited how much movable type spread in Korea. It was mostly used by the government for official books.

Europe

Johannes Gutenberg of Mainz, Germany, invented the printing press using a metal movable type system. As a goldsmith, Gutenberg knew how to cut punches for making coins from molds. Between 1436 and 1450, he developed the tools and methods for casting letters from special molds using a device called the hand mould. Gutenberg's hand mould was a key invention because it was the first practical way to make many cheap copies of letter punches, which was needed to print whole books.

Before Gutenberg, people copied books by hand or printed texts from hand-carved wooden blocks. Both methods took a very long time. Gutenberg and his team also created oil-based inks that worked perfectly with the printing press and paper.

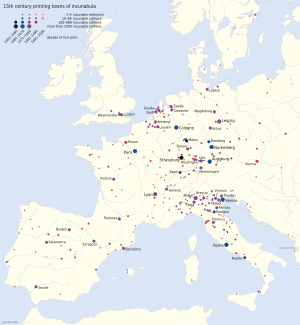

Gutenberg's movable-type printing system quickly spread across Europe. In just a few decades, from 1457 to 1480, the number of printing presses jumped from one in Mainz to 110 across Europe! Venice, Italy, quickly became a major center for printing.

Gutenberg's system had many advantages. The lead-antimony-tin alloy he used melted at a lower temperature than bronze, making it easier to cast the type. The antimony also made the type harder and more durable. With the reusable metal mold, one skilled worker could make 4,000 to 5,000 individual type pieces a day! This was much faster than the two years it took artisans to make 60,000 wooden types for Wang Zhen in China.

Making the Type Pieces

Making movable type pieces, especially in Europe, involved three main steps:

- Punchcutting: First, a skilled craftsman carved the design of each letter onto the end of a steel bar. This carved piece was called a "punch." They would check their work by making "smoke proofs," which were temporary prints made by holding the punch over a candle flame to get a thin layer of carbon. Each letter or symbol in a font needed its own punch.

- Matrix: The finished punch was then used to strike a blank piece of soft metal. This created a negative mold of the letter, called a "matrix."

- Casting: The matrix was placed at the bottom of a device called a "hand mould." Molten metal alloy (mostly lead and tin, with some antimony to make it hard) was poured into the mold. Antimony is special because it expands as it cools, which helps the cast letter have sharp, clear edges. Once the metal cooled, a rectangular block, about 4 cm long, was removed. This block was called a "sort." Any extra metal was trimmed off to make the sort the exact height needed for printing.

Setting the Type

In a printing shop, movable type pieces were kept in a special drawer called a "job case." This drawer had many small sections for different letters and symbols. The most popular design in America was called the California Job Case.

You might wonder why we call capital letters "upper case" and small letters "lower case." It's because, traditionally, the capital letters were stored in a separate drawer or case that was placed above the case holding the other letters!

The job case also held blank blocks called "spacers." These were used to separate words and fill out lines of text. For example, an "em space" was as wide as a capital "M," and an "en space" was half that width.

Individual letters were put together to form words and lines of text using a tool called a composing stick. Once a whole page of text was assembled, it was tightly bound together to create a "forme." All the letter faces in the forme had to be exactly the same height to create a flat surface for printing. The forme was then placed on a printing press, inked, and pressed onto paper to make the print.

Sometimes, special characters not usually found in the typical type case, like the "@" symbol, were called "sorts."

Combining Metal Type with Other Methods

It's sometimes thought that metal type completely replaced older printing methods, but that's not quite true. In the industrial age, printers chose the best method for the job. For example, printing very large letters for posters would have made metal type too heavy and expensive. So, large letters were often made from carved wood blocks or ceramic plates.

Also, if images were needed alongside text, they could be printed together if they were made as woodcuts or wood engravings, as long as these blocks were the same height as the metal type. However, if images were made using intaglio methods (like copper plates, which print from carved lines), then the images and text would have to be printed separately on different machines.

See also

In Spanish: Tipos móviles para niños

In Spanish: Tipos móviles para niños

- History of printing in East Asia

- History of Western typography

- Letterpress printing

- Odhecaton – the first sheet music printed with movable type

- Spread of European movable type printing

- Type foundry

- Typesetting

- Style guides

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |