Georgius Agricola facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Georgius Agricola

|

|

|---|---|

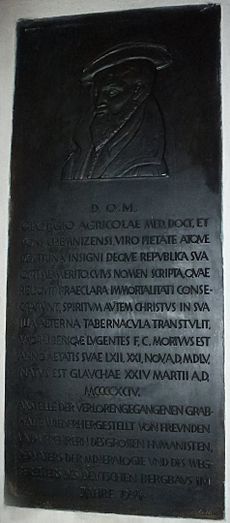

Georgius Agricola (fictive 1927 portrait)

|

|

| Born |

Georg Bauer

24 March 1494 Glauchau, Electorate of Saxony, Holy Roman Empire

|

| Died | November 21, 1555 (aged 61) Chemnitz, Electorate of Saxony, Holy Roman Empire

|

| Nationality | German |

| Citizenship | Holy Roman Empire |

| Alma mater | Leipzig University |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mineralogy |

Georgius Agricola (born Georg Bauer; 24 March 1494 – 21 November 1555) was a German scholar, mineralogist, and metallurgist during the Renaissance. He was born in Glauchau, a small town in what was then the Holy Roman Empire.

Agricola studied many subjects, but he was especially interested in mining and how to get metals from ores. He is often called the "Father of Mineralogy" because of his important book, De Natura Fossilium, published in 1546.

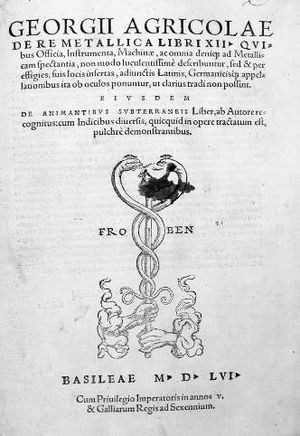

His most famous work is De re metallica libri XII, which came out in 1556, a year after he died. This book has 12 volumes and is a complete guide to mining, mining sciences, and metallurgy. Agricola studied these topics by watching them directly in nature. His book was very detailed and accurate, and it was used as the main reference for mining for 200 years. He wrote that he only included things he had seen, read, or heard about very carefully.

As a Renaissance scholar, Agricola believed in learning about everything. He published over 40 scholarly works on many topics, including medicine, geology, and history. His new ways of studying and observing helped change how science was understood during his time.

Contents

Understanding Georgius Agricola's Name

Georgius Agricola's birth name was Georg Pawer. The name Pawer is an old German word that means "farmer." His teacher, Petrus Mosellanus, suggested he change his name to a Latin version, which was common for scholars during the Renaissance. So, "Georg Pawer" became "Georgius Agricola." It's interesting that "Georgius" also comes from a Greek word meaning "farmer."

Some people call him the "Father of Mineralogy" and the founder of geology as a science. A poet named Georg Fabricius once called him "the distinguished ornament of the Fatherland."

Agricola's Early Life and Education

Youth and First Studies

Georg Pawer was born in 1494. He was the second of seven children. His father was a cloth maker and dyer. When he was 12, he went to a Latin school.

From 1514 to 1518, he studied at Leipzig University. He studied theology, philosophy, and languages like Greek and Latin. His first Latin teacher was Petrus Mosellanus, a famous humanist who followed the ideas of Erasmus.

Becoming a Humanist Scholar

Agricola was very smart. At just 24 years old, he became a special teacher of Greek at the Zwickau Greek school in 1519. In 1520, he published his first book, which was a Latin grammar guide for teachers.

In 1522, he went back to Leipzig to study more. His old teacher, Peter Mosellanus, supported him. Agricola also started studying medicine, physics, and chemistry.

In 1523, he traveled to Italy to continue his medical studies at the University of Bologna and possibly Padua. It's not clear where he got his medical degree. In 1524, he worked at the Aldine Press in Venice. This was a famous printing company that published many classic books. Agricola helped edit a large work about the ancient physician Galen until 1526.

Agricola's Professional Career

Working as a Town Physician

In 1527, Agricola returned to Germany and settled in Joachimsthal. This town was in the Ore Mountains and was a busy mining center because a lot of silver ore had been found there in 1516. Agricola worked as a town physician and pharmacist, but he also wanted to study mining.

His job as a doctor wasn't too demanding, so he spent most of his free time studying mining. Starting in 1528, he compared what others had written about minerals and mining with his own observations of the local mines and how they treated materials. He created a system to describe the rocks, minerals, and ores in the area. He also wrote about mining methods and processes he learned from miners.

For the first time, he explored how ores and minerals formed. He tried to understand the reasons behind these processes and put his findings into a clear system. He published his ideas in a book called Bermannus, sive de re metallica dialogus (Bermannus, or a dialogue on metallurgy) in 1530. The famous scholar Erasmus praised this book. Agricola also suggested that minerals and their effects on human health should be studied more.

Becoming Mayor of Chemnitz

In 1533, Agricola moved to Chemnitz to become the town physician. This was a very productive time for him. He soon became the lord mayor of Chemnitz and also worked as a diplomat and historian for George, Duke of Saxony. The Duke asked Agricola to write a large history book about the rulers of Saxony, which took 20 years to finish and was published in 1555.

In 1533, he published De Mensuris et ponderibus, a book about ancient Greek and Roman systems of measures and weights. At that time, there were no standard weights and measures in the Holy Roman Empire, which made trade difficult. This book helped Agricola become known as an important humanist scholar. He supported the idea of using standard weights and measures, which was a political stance.

In 1544, he published De ortu et causis subterraneorum (On Subterranean Origins and Causes). In this book, he criticized older ideas and laid the groundwork for modern physical geology. He discussed how wind and water shape the Earth, where groundwater and minerals come from, and how ore channels form.

In 1546, he published De natura eorum quae effluunt e terra (The nature of the things that flow out of the earth's interior). This book looked at the properties of water and air underground. Agricola believed that air underground caused earthquakes and volcanoes.

His book De Natura Fossilium (On the Nature of Fossils), also published in 1546, was a complete guide to minerals, ores, metals, gemstones, and rocks. He also wrote De animantibus subterraneis (On Subterranean Animals) in 1548 and other smaller works about metals. Agricola served as Burgomaster (lord mayor) of Chemnitz in 1546, 1547, 1551, and 1553.

Agricola's Famous Work: De re metallica

Agricola's most famous book, De re metallica libri xii, was published in 1556, the year after he died. It was probably finished around 1550, but it took time to print because it had many detailed woodcut illustrations. This book is a systematic and illustrated guide to mining and how to get metals from ores.

Before Agricola's book, Pliny the Elder's Historia Naturalis was the main source of information on metals and mining. Agricola learned from ancient writers like Pliny and Theophrastus. He made many references to Roman works.

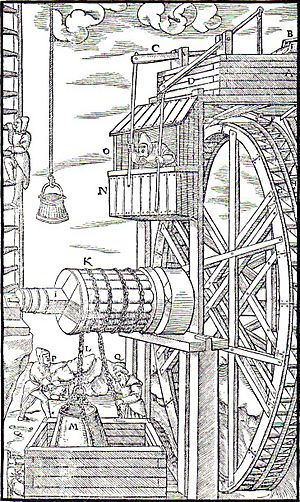

In geology, Agricola explained and showed how ore veins are found in the ground. He described how to search for ore veins and how to survey mines in great detail. He also explained how to wash ores to collect valuable minerals like gold and tin. The book shows water mills used in mining. These mills were used to lift people and materials out of mine shafts. They also crushed ores to get fine particles of gold and other heavy minerals. Water mills were also used to power giant bellows that forced air into underground mine tunnels.

Agricola described mining methods that are no longer used today, such as fire-setting. This method involved building fires against hard rock faces. The hot rock was then quickly cooled with water, which caused it to crack and become easier to remove. This was a dangerous method underground and was later replaced by explosives.

The book includes an appendix that lists the German words for the technical terms used in the Latin text. Some modern words, like fluorspar (from which fluorine was later named) and bismuth, come from his work. Agricola also gave the name basalt to a black rock he found, which became a common term in geology.

In 1912, an English translation of De re metallica was published. It was translated by Herbert Hoover, an American mining engineer, and his wife Lou Henry Hoover. Herbert Hoover later became the President of the United States.

Agricola's Death

Georgius Agricola died on November 21, 1555. His friend, the poet Georg Fabricius, wrote that Agricola had been healthy his whole life but died after a four-day fever.

Agricola was a strong Catholic. Because of his religious beliefs, he was not allowed to be buried in the main church in Chemnitz, even though he had been the lord mayor. The Protestant leader in Chemnitz, Tettelbach, asked Prince August to refuse the burial.

So, four days later, Agricola's body was taken to Zeitz, which was over 50 kilometers (30 miles) away. His childhood friend, Bishop Julius von Pflug, buried him in the Zeitz cathedral. Agricola's wife had a memorial plate placed inside the cathedral, but it was removed in the 17th century.

See also

In Spanish: Georgius Agricola para niños

In Spanish: Georgius Agricola para niños

- List of mineralogists

- Shen Kuo, 11th-century Chinese author on land formation and mineralogy

- Theophrastus

- Mineral collecting