Galen facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Galen

|

|

|---|---|

| Κλαύδιος Γαληνός | |

An 18th century engraving by Georg P. Busch.

|

|

| Born | AD 129 |

| Died | c. AD 216 (aged c. 87) Unknown

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Anatomy Medicine Philosophy |

| Influences | Hippocrates Plato Aristotle Herophilos |

| Influenced | Hunain ibn Ishaq Giovanni Battista Monte Andreas Vesalius William Harvey |

Galen (born September 129 AD, died around 216 AD) was a very important Greek physician, surgeon, and philosopher. He lived during the time of the Roman Empire. Many people consider him one of the greatest medical researchers from ancient times.

Galen's ideas greatly influenced many areas of science. These included anatomy (the study of body structure), physiology (how the body works), pathology (the study of diseases), pharmacology (the study of medicines), and neurology (the study of the nervous system). He also influenced philosophy and logic.

Galen was born in Pergamon, an ancient city now in Turkey. His father was a rich architect who loved learning. Galen received an excellent education. He traveled widely to learn about different medical ideas. Later, he settled in Rome. There, he became a doctor for important Roman citizens and even for several emperors.

Galen's understanding of the body was based on the idea of the four humors. This theory said that the body had four main fluids: black bile, yellow bile, blood, and phlegm. He believed that these humors affected a person's health and mood. Galen's medical ideas were followed in the Western world for over 1,300 years.

Since dissecting human bodies was not allowed back then, Galen studied the anatomy of animals, especially apes. He believed that animal bodies were similar enough to human bodies. His ideas about anatomy were accepted for a very long time. They were only seriously challenged in 1543 when Andreas Vesalius published his work based on human dissections. Galen's ideas about how blood moved in the body were also believed for centuries. However, in the 1200s, a scholar named Ibn al-Nafis discovered how blood flows through the lungs.

Galen saw himself as both a doctor and a philosopher. He even wrote a book called That the Best Physician Is Also a Philosopher. He used direct observation, animal dissection, and even vivisection (studying living animals) in his research. Many of his writings have survived, showing his complex approach to medicine.

Contents

Biography

Galen's Greek name, Galēnós, means 'calm'. His Latin name, Aelius or Claudius, suggests he was a Roman citizen.

Galen wrote about his early life in a book. He was born in September 129 AD. His father, Aelius Nicon, was a wealthy and kind architect. He was interested in many subjects like philosophy, math, and astronomy. Pergamon, Galen's hometown, was a major center for learning. It had a famous library and a large temple dedicated to Asclepius, the god of healing. Galen started learning about philosophy at age 14. His father wanted him to become a philosopher or politician. However, Galen said that his father had a dream around 145 AD. In this dream, Asclepius told his father to send Galen to study medicine.

Medical education

At 16, Galen began studying medicine at the local healing temple, called an Asclepeion. He spent four years there as an attendant. These temples were like ancient spas or hospitals. Sick people would come to seek healing from the priests. Many important Romans visited the temple in Pergamon.

When Galen was 19, his father died, leaving him wealthy. He then traveled widely to study medicine, following the advice of Hippocrates. He visited cities like Smyrna, Corinth, and Alexandria, which had a great medical school. He learned from many different medical teachers.

In 157 AD, at age 28, Galen returned to Pergamon. He became the doctor for the gladiators. These were fighters who entertained crowds. Galen claimed he got the job after showing his surgical skills on an ape. He challenged other doctors to fix the damage, and when they couldn't, he did it himself. For four years, he learned a lot about diet, fitness, hygiene, and treating severe injuries. He called the gladiators' wounds "windows into the body." During his time, only five gladiators died, compared to sixty under the previous doctor. This success was likely due to his careful attention to their wounds.

Rome

Galen moved to Rome in 162 AD and quickly became a well-known doctor. His public demonstrations and strong opinions often led to disagreements with other doctors in the city. When his philosophy teacher, Eudemus, fell ill, Galen treated him. Other Roman doctors criticized Galen for using a prognosis (predicting the course of an illness). They preferred methods based on divination or mysticism. Galen defended his approach, saying doctors must "observe and reason."

However, Eudemus warned Galen that these conflicts could be dangerous. He even suggested that some doctors might try to poison him. Because of these serious disagreements, Galen feared for his safety and left Rome.

In 169 AD, a great plague spread through Rome. The emperor Marcus Aurelius called Galen back to serve as the court physician. Galen was asked to go with the emperors to Germany, but he was later allowed to stay in Rome. He became the doctor for the emperor's son, Commodus. During this time, Galen wrote many important medical books. Sadly, both Emperor Lucius Verus and Marcus Aurelius later died from the plague.

Galen was Commodus's doctor for many years, treating his common illnesses. He also served Septimius Severus as a physician.

The Antonine Plague

The Antonine Plague was a major epidemic named after Emperor Marcus Aurelius's family. It's also known as the Plague of Galen because he saw it firsthand. He was in Rome when it started in 166 AD and also during an outbreak among soldiers in 168–69 AD. Galen described the symptoms and his treatments for this long-lasting disease.

The plague was very deadly, causing millions of deaths across the Roman Empire. Although Galen's description is not complete, it helps experts identify the disease as smallpox.

Later years

Galen continued to work and write in his later years. He finished books on medicines and a guide for diagnosing and treating illnesses. These writings became very influential in medicine for centuries.

Some sources say Galen died at age 70, around 199 AD. However, other sources, especially Arabic ones, say he lived to be 87, dying around 216 AD. These sources claim his tomb in Palermo, Sicily, was still well-preserved in the 10th century. Many experts now believe the Arabic sources are more accurate.

Medicine

Galen greatly improved our understanding of how diseases work. He supported the Hippocratic theory of the four bodily humors: blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm. He believed that imbalances in these fluids caused different human moods and temperaments. For example, too much blood meant a "sanguine" (optimistic) temperament, while too much black bile meant a "melancholic" (sad) temperament.

Galen was also a skilled surgeon. He performed operations on people, including on brains and eyes. To treat cataracts, he used a needle-shaped tool to remove the affected lens of the eye, similar to modern procedures. He also experimented by tying off arteries in living animals. Galen knew that the eye's lens was at the front, not in the exact center as some later historians thought.

At first, Galen was hesitant, but then he strongly promoted Hippocratic ideas like bloodletting. This practice involved removing blood from a patient. Some doctors in Rome disagreed, but Galen defended it in his books and public debates. His work on anatomy remained unmatched in Europe until the 16th century.

Anatomy

Galen was very interested in human anatomy. However, Roman law around 150 BCE made it illegal to dissect human bodies. Because of this, Galen studied the anatomy of animals, especially primates, through both dissection (studying dead animals) and vivisection (studying living animals). He believed that animal bodies were very similar to human bodies.

Galen made important discoveries about the trachea (windpipe) and was the first to show that the larynx (voice box) produces sound. In one experiment, he used bellows to inflate the lungs of a dead animal. His research was influenced by earlier thinkers like Plato, Aristotle, and Hippocrates. He was one of the first to use experiments to research medical findings.

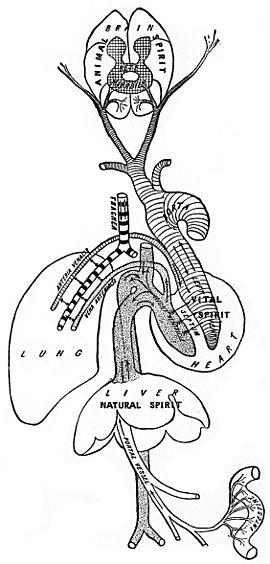

One of Galen's biggest contributions was his work on the circulatory system. Before him, people thought arteries carried air, not blood. He was the first to realize that venous (dark) and arterial (bright) blood were different.

Galen had many ideas about how the circulatory system worked. He believed blood was made in the liver from digested food. This blood then flowed into the right side of the heart. He also thought that the venous artery (now known as the pulmonary vein) carried air from the lungs to the left side of the heart. He believed this air mixed with blood from the right side, which passed through tiny holes in the wall (septum) between the heart's two sides. This mixed blood then went out to the body. He also thought waste products went back to the lungs to be exhaled.

While his animal experiments helped him understand many body systems, his ideas about circulation had some errors. Galen thought there were two separate one-way systems for blood, not one unified system. He believed blood was used up by the organs and then regenerated. These ideas were later proven wrong, starting with the work of Ibn al-Nafis around 1242.

Galen also made important discoveries about the human spine. His animal studies helped him accurately describe the spine, spinal cord, and vertebral column. He also played a big role in understanding the Central Nervous System. He described the nerves coming from the spine. Galen was the first doctor to study what happens when the spinal cord is cut at different levels. He worked with pigs, cutting different nerves to see how it affected their bodies. He also studied diseases affecting the spinal cord and nerves. In one of his books, he explained the difference between motor (movement) and sensory nerves (feeling).

Through his vivisection experiments, Galen also proved that the voice is controlled by the brain. In a famous public experiment, he would cut open a squealing pig. Then, he would tie off the nerves to its vocal cords, showing that this stopped the sound. He used similar methods to study how kidneys and the bladder work.

Galen believed the human body had three connected systems:

- The brain and nerves, for thought and sensation.

- The heart and arteries, for providing life energy.

- The liver and veins, for nutrition and growth.

He thought blood was made in the liver and then sent throughout the body.

Localization of function

One of Galen's important books, On the Doctrines of Hippocrates and Plato, tried to show how the ideas of these two thinkers were connected. Using their theories, along with Aristotle's, Galen developed a theory of a three-part soul. He used Plato's terms: rational, spiritual, and appetitive.

Galen believed each part of the soul was located in a specific part of the body. This idea is called "localization of function."

- The rational soul was in the brain, controlling thinking, memory, and voluntary movement.

- The spiritual soul was in the heart, controlling growth, life, and strong emotions like anger.

- The appetitive soul was in the liver, controlling basic urges like hunger and pleasure.

To connect these ideas, Galen used the theory of pneuma (a kind of vital spirit). He said there was vital pneuma in the arteries and psychic pneuma in the brain and nervous system. He believed the vital pneuma was in the heart and the psychic pneuma in the brain. He did many animal studies, like on an ox, to understand how vital pneuma changed into psychic pneuma. Even though he was criticized for comparing animal anatomy to human anatomy, Galen was confident in his knowledge.

In his book On the usefulness of the parts of the body, Galen argued that the perfect design of each body part showed that an intelligent creator must exist.

Philosophy

Even though he focused on medicine, Galen also wrote about logic and philosophy. His ideas were shaped by earlier Greek and Roman thinkers like Plato, Aristotle, and the Stoics. Galen believed that medicine should combine philosophical thinking with practical work. He thought the best doctors used theory, observation, and experiments together.

Galen combined his observations from dissections with Plato's ideas about the soul. Plato believed the body and soul were separate. Galen thought that the soul had to be "acquired" because it didn't always stay within the human body. Plato's influence is seen in Galen's idea of arterial blood. He thought it was a mix of nutritious blood from the liver and the "vital spirit" (the soul) from the lungs. This vital spirit was needed for the body to work and was eventually used up, so the process had to repeat.

During Galen's time, there were different schools of thought in medicine:

- Empiricists focused on practical experience and experiments.

- Rationalists (or Dogmatists) valued studying established teachings to create new theories.

- Methodists were a middle group, using pure observation and studying how illnesses naturally progressed.

Galen's education exposed him to all these ideas. He learned from both Rationalist and Empiricist teachers.

Opposition to the Stoics

Galen was known for his medical advances, but he also cared about philosophy. He created his own three-part soul model, similar to Plato's. Galen also developed a personality theory based on his understanding of body fluids. He believed mental problems had a physical cause. Galen connected many of his theories to the pneuma (vital spirit) and disagreed with the Stoics' ideas about it.

Galen believed the Stoics couldn't explain where the mind's functions were located. Through his medical studies, he was convinced the brain was the answer. The Stoics thought the soul had only one part, the rational soul, and that it was in the heart. Galen, following Plato, added two more parts to the soul.

Galen also rejected the Stoics' logic system. Instead, he used a type of logic influenced by Aristotle.

Psychology

Mind–body problem

Galen believed there was no clear separation between the mind and the body. This was a debated idea at the time. Galen agreed with some Greek philosophers who thought the mind and body were connected. He believed he could prove this scientifically. This was a key point where he disagreed with the Stoics. Galen suggested that different organs in the body were responsible for specific functions. He argued that the Stoics lacked scientific proof for their idea of a separate mind and body.

Psychotherapy

Another important work by Galen, On the Diagnosis and Cure of the Soul's Passion, discussed how to approach and treat psychological problems. This was an early form of what we now call psychotherapy. His book gave instructions on how to counsel people with mental issues. The goal was to help them reveal their deepest feelings and secrets, and then heal their mental problems. Galen believed that strong emotions caused these psychological issues. He suggested that the counselor should be an older, wise man who was free from strong emotions himself.

Published works

Galen may have written more than any other ancient author. It is said he had twenty scribes writing down his words. He might have written as many as 500 books, totaling about 10 million words. Even though only about 3 million words survive, this is still a huge amount. In 191 AD, a fire in the Temple of Peace in Rome destroyed many of his works, especially his philosophy books.

Because Galen's works were not translated into Latin early on, and because the Roman Empire in the West declined, the study of Galen almost disappeared in Western Europe during the Early Middle Ages. However, in the Eastern Roman Empire, his works continued to be studied. Later, after 750 AD, Arab Muslims became interested in Greek science and medicine. They had many of Galen's texts translated into Arabic, often by Syrian Christian scholars. Because of this, some of Galen's writings only exist today in Arabic translations. For some ancient sources, we only know about their work because Galen wrote about them.

Even in his own time, fake or poorly edited versions of his works were a problem. This led him to write On his Own Books. Fake versions continued to appear until the Renaissance. Some of Galen's books have also appeared under many different titles over the years. It can be hard to find and study all his works. There is no single complete collection of his writings, and experts still debate if some works truly belong to him.

Many attempts have been made to organize Galen's vast writings. The most complete collection was put together by Karl Gottlob Kühn between 1821 and 1833. This collection has 122 of Galen's books, translated from Greek into Latin. It is over 20,000 pages long and fills 22 volumes.

Legacy

Late Antiquity

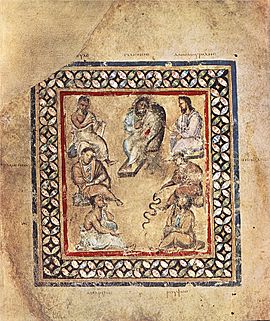

In his time, Galen was famous as both a doctor and a philosopher. Emperor Marcus Aurelius called him "first among doctors and unique among philosophers." Other writers of the time also praised him. A poet in the 7th century even called Christ a "second and neglected Galen." Galen's ideas continued to strongly influence medicine until the mid-17th century in the Byzantine, Arabic, and European worlds.

Galen brought together and explained the work of earlier doctors. His writings, known as "Galenism," were how Greek medicine was passed down through generations. He restated and reinterpreted many ideas. The full importance of his contributions was not understood until long after his death. Galen's powerful writing made it seem like there was little more to learn in medicine. The term "Galenism" can mean both a positive change in ancient medicine and a negative one, as it sometimes stopped further progress.

After the Western Roman Empire fell, the study of Galen's works almost disappeared in the Latin West. However, in the Greek-speaking Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantium), many scholars copied and spread Galen's works. This made them more accessible. In later times, medical writing became more theoretical, with many authors just debating Galen's ideas. Other medical groups slowly disappeared because Galen's influence was so strong.

Greek medicine was part of Greek culture. Syrian Christians learned about it when the Byzantine Empire ruled Syria and Mesopotamia. After 750 AD, these Syrian Christians began translating Galen's works into Syriac and Arabic. From then on, Galen's ideas became part of medicine in the medieval Islamic Middle East.

Medieval Islam

Galen's approach to medicine became very important in the Islamic world. The first major translator of Galen into Arabic was Hunayn ibn Ishaq, an Arab Christian. He translated 129 of Galen's works into Arabic between 830 and 870 AD. Arabic sources continue to help us discover new or hard-to-find writings by Galen. One of Hunayn's Arabic translations, Kitab ila Aglooqan fi Shifa al Amrad, is considered a masterpiece. This 10th-century manuscript describes different types of fevers and inflammations. It also lists over 150 plant and animal-based remedies. This book helps us understand ancient Greek and Roman treatment methods.

Galen's works were not accepted without question in the Islamic world. Scholars like Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi wrote books like Doubts on Galen. Doctors like Ibn al-Nafis also challenged his ideas. Islamic scholars focused on experiments and observations. They compared their new findings with Galen's. For example, Ibn al-Nafis's discovery of how blood flows through the lungs went against Galen's theory about the heart.

Galen's writings, including his humorism theory, are still important in modern Unani medicine. This system is closely linked to Islamic culture and is practiced in places like India and Morocco. Maimonides, a famous Jewish scholar, was also influenced by Galen. He often quoted Galen in his medical works and thought he was the greatest doctor ever.

Middle Ages

From the 11th century onwards, Latin translations of Islamic medical texts began to appear in Western Europe. These were soon added to the courses at universities like Naples and Montpellier. From that time, Galen's ideas gained new, strong authority. He was even called the "Medical Pope of the Middle Ages." Constantine the African was one of the people who translated both Hippocrates and Galen from Arabic.

Galen's books on anatomy and medicine became the main part of a medieval doctor's university studies. They were studied alongside Ibn Sina's The Canon of Medicine, which expanded on Galen's works. Unlike ancient Rome, Christian Europe did not completely ban the dissection of human bodies. Such examinations were done regularly from at least the 13th century. However, Galen's influence was so great that when dissections showed differences from Galen's anatomy, doctors often tried to make them fit his system. Some even said that human anatomy had changed since Galen's time.

Renaissance

The Renaissance and the Fall of Constantinople (1453) brought many Greek scholars and manuscripts to the West. This allowed people to compare the Arabic translations with Galen's original Greek texts. This "New Learning" and the Humanist movement helped make Galen's works part of the Latin scientific studies. Debates about medical science now had two traditions: the more traditional Arabic and the more open Greek. Some extreme movements began to challenge the idea of authority in medicine. For example, Paracelsus famously burned the works of Avicenna and Galen at his medical school.

However, Galen's importance among great thinkers is shown by a 16th-century painting in a monastery. It shows ancient wise men, with Galen placed between a prophetess and Aristotle.

Galenism was finally overcome by the ideas of Paracelsus and the work of Italian Renaissance anatomists like Andreas Vesalius in the 16th century. In the 1530s, Vesalius began translating many of Galen's Greek texts into Latin. Vesalius's most famous work, De humani corporis fabrica, was greatly influenced by Galen's writing style. However, Vesalius showed that Galen's descriptions of anatomy were sometimes based on monkeys, not humans. He showed Galen's limitations through books and demonstrations, despite strong opposition from doctors who still believed in Galen. Since Galen himself said he used monkey observations (because human dissection was forbidden), Vesalius could present himself as following Galen's method of direct observation, but on human bodies, which was now allowed. Vesalius's examinations also disproved some medical theories of Aristotle. One famous example was Vesalius showing that the wall between the heart's chambers was not permeable, as Galen had taught.

Another important step beyond Galen's ideas came from studies of human circulation by Andrea Cesalpino and William Harvey. However, some of Galen's teachings, like using bloodletting for many illnesses, remained influential until the 19th century.

Contemporary scholarship

Studying Galen's work is still an active and important field today. There has been renewed interest in his writings.

Copies of his works translated by Robert M. Green are kept at the National Library of Medicine in Bethesda, Maryland.

In 2018, the University of Basel discovered a mysterious Greek papyrus with writing on both sides. It was found to be an unknown medical document by Galen or a commentary on his work. The text describes a condition called 'hysterical apnea'.

See also

In Spanish: Galeno para niños

In Spanish: Galeno para niños

- Abascantus

- Galenic formulation

- Timeline of medicine and medical technology

- History of medicine

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |