Erasmus facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Erasmus

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Portrait of Erasmus of Rotterdam (1523)

by Hans Holbein the Younger |

|||||||

| Born | c. 28 October 1466 |

||||||

| Died | 12 July 1536 (aged 69) Basel, Old Swiss Confederacy

|

||||||

| Other names |

|

||||||

| Academic background | |||||||

| Education | Queens' College, Cambridge University of Paris University of Turin (DD, 1506) |

||||||

| Academic advisors | Paulus Bombasius and Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples (epistolary correspondents) | ||||||

| Influences | |||||||

| Academic work | |||||||

| Era | Renaissance philosophy 16th-century philosophy |

||||||

| School or tradition |

|

||||||

| Institutions | University of Leuven | ||||||

| Notable students | Damião de Góis | ||||||

| Main interests |

|

||||||

| Notable works |

|

||||||

| Notable ideas |

|

||||||

| Influenced |

|

||||||

|

|||||||

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus (born October 28, 1466, died July 12, 1536), known as Erasmus of Rotterdam, was a famous Dutch thinker and Catholic priest. He is known as one of the most important scholars of the Renaissance. This was a time of great new ideas in Europe.

Erasmus was called the "Prince of the Humanists." Humanists studied old Greek and Roman texts. He used these skills to create new Latin and Greek versions of the New Testament. These new versions helped start important discussions during the Protestant Reformation. He also wrote many books, including In Praise of Folly and Handbook of a Christian Knight.

Erasmus lived when Europe was going through big religious changes. He stayed a member of the Catholic Church his whole life. He wanted to fix problems within the Church. He believed people had "free will" to choose good or bad. This idea was different from what some other reformers believed. His balanced approach sometimes made people on both sides unhappy.

Erasmus died in Basel in 1536. He was getting ready to go back to his home region. He was buried in the main church of Basel.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Desiderius Erasmus was born around October 28, 1466. He was likely born in Rotterdam or Gouda, in what is now the Netherlands. He was named after Saint Erasmus. His parents were not married when he was born. His father was Gerard, and his mother was Margaretha Rogerius. She was the daughter of a doctor.

Erasmus and his older brother Peter were cared for by their parents. Sadly, both parents died from the plague in 1483. This made Erasmus feel that his birth was a "stain" on his life.

He received the best education available at the time. He went to monastic schools. In 1475, he went to a good Latin school in Deventer. Here, he started learning Greek. This was unusual for a school that was not a university. He also learned about having a personal connection with God. However, he did not like the strict rules of the religious teachers. His schooling ended around 1483 when the plague hit. His mother, who had moved to be near her sons, also died.

Becoming a Priest

Around 1487, Erasmus was poor. This led him to join a religious group called the Augustinian canons in Stein, South Holland. He took his vows in 1488. He became a Catholic priest on April 25, 1492. He did not seem to work as a priest for very long. He later spoke out against some problems he saw in religious orders. He wanted to reform the Church from the inside.

Soon after becoming a priest, he got a chance to leave the monastery. He was offered a job as a secretary to the Bishop of Cambrai. He was chosen because he was very good at Latin. He got special permission to leave his vows temporarily. This was because of his health and his love for studying. Later, Pope Leo X made this permission permanent. This was a big deal at the time.

Studies and Travels

In 1495, Erasmus went to study at the University of Paris. He did not like the strict rules there. He became good friends with an Italian humanist named Publio Fausto Andrelini.

In 1499, he was invited to England. He made many important friends there. These included John Colet and Thomas More. Through John Colet, Erasmus became more interested in theology. He taught at the University of Cambridge from 1510 to 1515. He stayed at Queens' College. He often complained about the food and weather in England. He wanted to learn Greek better to study Christian history.

Erasmus had poor health. He said Queens' College did not have enough good wine. Wine was used as medicine for gallstones, which he had. Today, Queens' College has an Erasmus Building and an Erasmus Room. Many of his first books are still in the college library.

He taught at the University of Oxford during his first visit to England in 1499. He was very impressed by John Colet's Bible teaching. This made him want to learn Greek well. He wanted to study theology more deeply. He also wanted to prepare a new edition of the Bible. He studied Greek day and night for three years. He often asked friends for books and money for teachers.

Erasmus wanted to be an independent scholar. He avoided jobs that would limit his freedom. He turned down important offers in England. He helped his friend John Colet by writing Greek textbooks. In 1506, he went to Italy. He earned his Doctor of Divinity degree from the University of Turin. He then traveled to Venice. There, a larger version of his book Adagia was printed.

He taught at the University of Leuven. Here, he faced criticism from people who did not like his ideas. In 1517, he supported starting a new college there. It was called the Collegium Trilingue. It taught Hebrew, Latin, and Greek. But he felt unwelcome in Leuven. So, he moved to Basel, Switzerland. There, he could express his ideas freely. He became good friends with the publisher Johann Froben. Together, they published over 200 of his works.

Erasmus's New Testament

Creating a New Bible Text

In Spain, Cardinal Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros started a project in 1502. He wanted to create a Bible in four languages: Greek, Hebrew, Aramaic, and Latin. His team finished the New Testament in 1514. They even made special printing types for Greek.

Erasmus was also working on his own new Latin New Testament. He also wanted to make a new Greek text. He got permission to publish his work first. In 1516, his Novum Instrumentum omne was published. This was the first published Greek New Testament. Pope Leo X approved it. The Spanish team's Bible was approved in 1520 but not released until 1522.

Erasmus rushed his work to be first. This caused some mistakes and typos. He had to print more editions later to fix them.

Erasmus's Latin Translation

Erasmus worked for years on two projects. One was collecting Greek texts. The other was creating a new Latin New Testament. He started his Latin New Testament in 1512. He gathered old Latin Bible copies to make a better version. He wanted to improve the language. He said, "It is only fair that Paul should address the Romans in somewhat better Latin."

He included the Greek text so scholars could check his Latin translation. He called his work Novum Instrumentum omne (All of the New Teaching). Later, he called it Novum Testamentum omne (All of the New Testament). This showed he believed both Greek and Latin versions were important.

His Impact on the Bible

Erasmus helped bring together the Greek and Latin Bible traditions. He made sure both were present and similar in content. He even changed some Greek text to match his Latin version. For example, the last six verses of the Book of Revelation were missing from his Greek copy. So, Erasmus translated them from the Latin Bible back into Greek.

Published Editions

Erasmus said his first edition was "rushed into print rather than edited." It had many errors. His friend Johann Froben published it in 1516. This was the first published Greek New Testament. Erasmus used several Greek manuscripts. But he did not have a single complete one. He also did not use some older, better manuscripts.

In the second edition (1519), he used the more common word Testamentum. Martin Luther used this edition for his German Bible translation. The first two editions sold 3,300 copies. The Spanish Bible only printed 600 copies. These early editions did not include a specific Bible verse (1 John 5:7–8). Erasmus could not find it in any Greek manuscript. It was added in the third edition (1522). This verse is rarely in modern Bibles today.

The third edition (1522) was used by William Tyndale for the first English New Testament. Erasmus published a fourth edition in 1527. It had Greek, Latin Vulgate, and Erasmus's Latin texts side-by-side. His fifth and final edition came out in 1535. Later Greek New Testaments, based on Erasmus's work, became known as the Textus Receptus.

Erasmus dedicated his work to Pope Leo X. He saw it as his most important service to Christianity. He also wrote Paraphrases of the New Testament. These were popular versions of Bible books. They were published in Latin and quickly translated into other languages.

Erasmus and the Reformation

Staying Neutral in Disputes

The Protestant Reformation began soon after Erasmus published his Greek New Testament in 1516. This was a big challenge for Erasmus. The arguments between the Catholic Church and the new Protestant movement became very strong. Everyone was asked to pick a side. Erasmus was very famous, but he did not like taking sides.

People had laughed at his book In Praise of Folly. But few had bothered him. He believed his work was good for smart people and religious leaders. Erasmus wrote in Greek and Latin. These were the languages of scholars. So, his ideas reached a small, educated group.

Disagreements with Luther

Martin Luther believed that humans could not choose good on their own. He said sin made them unable to reach God. Erasmus saw Luther as a "mighty trumpet of gospel truth." He agreed that many of Luther's ideas for reform were needed. Erasmus respected Luther, and Luther admired Erasmus's learning. Luther hoped Erasmus would join his side.

But Erasmus refused to commit. He said it would hurt his role as a leader in scholarship. He believed he could only help reform religion as an independent scholar. Luther became angry when Erasmus hesitated. He thought Erasmus was avoiding responsibility. However, Erasmus's hesitation might have been because he worried about the growing disorder and violence of the reform movement.

In 1529, Erasmus wrote about the Reformers. He complained about their beliefs and actions. He also worried about changes to Church teachings. He believed the Church's long history protected it from new, wrong ideas.

Erasmus tried to stay neutral in these religious arguments. But both sides accused him of being with the other. This was probably because he would not pick a side.

In his book Explanation of the Apostles' Creed (1533), Erasmus disagreed with Luther. He said that Church traditions were as important as the Bible. He also listed more books in the Bible than Luther did. He supported the seven sacraments. He also said that questioning the perpetual virginity of Mary was wrong. However, he did support ordinary people being able to read the Bible.

Luther called Erasmus names, like "viper" and "liar." He even said Erasmus was "the very mouth and organ of Satan."

The Idea of Free Will

Erasmus entered the debate about "free will." This was a very important question. In his book De libero arbitrio diatribe sive collatio (1524), he discussed Luther's view on free will. He presented both sides of the argument fairly. This book did not push for one side. This was good for Erasmus's supporters but bad for Luther's. Luther responded with his own book, On the Bondage of the Will (1525). He attacked Erasmus and his book. He even said Erasmus was not a Christian. Erasmus replied with a long two-part book called Hyperaspistes (1526–27).

In this debate, Erasmus showed he believed more in free will than Luther did. For Erasmus, the main point was that humans can make choices. Erasmus used ideas from many famous thinkers. These included early Church leaders like Origen and Augustine. He also used ideas from later scholars like Thomas Aquinas.

As Luther's ideas grew, social problems began to appear. These included peasant wars and other disturbances. Erasmus was worried by these events. He was glad he had stayed out of the extreme parts of the reform. But Catholics still blamed him for starting the "tragedy" of Protestantism.

When the city of Basel became Protestant in 1529, Erasmus left. He moved to Freiburg im Breisgau. He left because he feared losing his neutral position.

Religious Tolerance

Some of Erasmus's writings helped create the idea of religious tolerance. For example, in De libero arbitrio, he said that people arguing about religion should use calm language. He believed this would help them find the truth. He thought that truth is found when people talk together peacefully. Erasmus did not oppose punishing heretics, but he usually argued for moderation. He was against the death penalty. He wrote, "It is better to cure a sick man than to kill him."

Important Writings

Erasmus wrote about Church topics and general human interests. By the 1530s, his books made up 10 to 20 percent of all book sales in Europe.

He helped create a collection of Latin proverbs called Adagia. He is known for saying, "In the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king." He is also often given credit for the phrase "Pandora's box." This came from a mistake in his translation of an old Greek story.

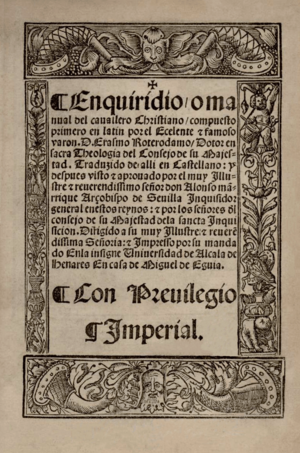

His serious writings include Enchiridion militis Christiani, the "Handbook of the Christian Soldier" (1503). In this book, Erasmus described how a normal Christian should live. He said the biggest problem was just following traditions without understanding them. He believed that religious forms could help people worship God. But they could also hide or stop the true spirit of faith. He talked about problems in monasteries, saint worship, and war. The Enchiridion was like a sermon. Erasmus challenged common ideas. He said priests should share their knowledge with everyone. He stressed personal spiritual practices. He called for a reform that would return to the early Church leaders and the Bible. He believed reading the Bible was very important. It could change people and make them loving. He wrote that the New Testament is Christ's law, and people should obey it. They should also try to be like Christ.

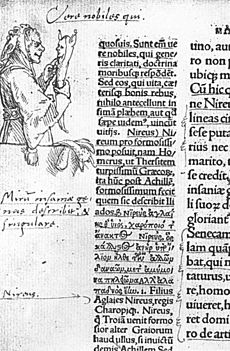

Erasmus's most famous work is The Praise of Folly. He wrote it in 1509 and published it in 1511. It is a funny attack on superstitions and traditions in European society. It also criticized the Western Church. He dedicated it to his friend Thomas More.

The Education of a Christian Prince (1516) was written as advice for the young King Charles of Spain. Charles later became Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor. Erasmus said a prince should be honest and serve his people. This book was published three years after Niccolò Machiavelli's The Prince. Machiavelli said it was safer for a prince to be feared than loved. Erasmus believed a prince should be loved. He thought a good education would help a prince rule fairly and kindly. This would prevent him from becoming a harsh ruler.

Erasmus often argued with people who were sympathetic to his ideas. One was Ulrich von Hutten. He was a smart but unpredictable person who supported Luther. Hutten said Erasmus should do the same. In his reply in 1523, Erasmus said Hutten had misunderstood him. He repeated that he would never leave the Church.

Erasmus was always interested in language. In 1525, he wrote a whole book about it called Lingua. This book and others helped start ideas about the philosophy of language.

His book Ciceronianus came out in 1528. It criticized a Latin writing style that only copied Cicero.

Erasmus's last big work was Ecclesiastes (1536). It was a huge guide for preachers, about a thousand pages long. It gave advice on almost every part of being a preacher. It used many examples from old Greek and Roman writings and the Bible.

Sileni Alcibiadis (1515)

Erasmus's Sileni Alcibiadis is one of his most direct calls for Church reform. It was published in 1515. The word Sileni refers to a figure that looks plain or ugly on the outside but is beautiful or wise on the inside. Alcibiades was a Greek politician.

Erasmus used this idea to say that true wisdom is not found in fancy titles or clothes. He said that people with grand titles are often far from true wisdom. He listed several examples of "Sileni." He even wondered if Christ was the most important Silenus. The Apostles were also Sileni because others made fun of them.

Erasmus believed that the simplest things can be the most important. He said the Church is all Christian people. He criticized leaders who spent the Church's money on themselves. He believed the Church's real purpose was to help people live Christian lives. He said priests should be pure. He criticized the wealth of the popes. He thought the Gospel should be the most important thing.

Death and Legacy

When Erasmus became weak, he planned to move to Brabant. But in 1536, he suddenly died from dysentery while visiting Basel. He had stayed loyal to the Pope. But he did not receive the last rites of the Catholic Church. Reports of his death do not say if he asked for a priest. This fits with his belief that outward signs were not as important as a person's direct connection with God. His last words were "Dear God." He was buried with a big ceremony in the Basel Minster.

His books were very popular. They have been printed and translated many times since the 1500s. He translated or edited works by many famous writers. These include Saint Augustine and Saint Jerome.

In his hometown of Rotterdam, the Erasmus University Rotterdam is named after him. The city's metro line was also named Erasmuslijn for a time. In 2003, the Foundation Erasmus House was started. It celebrates Erasmus's life. Three days each year celebrate him. April 1 celebrates his book The Praise of Folly. July 11 is the Night of Erasmus, celebrating his lasting influence. His birthday is celebrated on October 28.

People's opinions of Erasmus have changed over time. Moderate Catholics saw him as a leader in Church reform. Protestants saw his early support for Luther. They also saw how he helped prepare for the Reformation through his Bible studies. But after his death, many Protestants criticized him. They did not like that he criticized Luther. They also did not like that he supported the Catholic Church his whole life.

However, Erasmus wanted to heal the divide in Christianity. He left his works to his friend Sebastian Castellio. Castellio worked to bring together Catholics, Anabaptists, and Protestants.

Later, during the Age of Enlightenment, Erasmus became a respected symbol again. He was seen as an important figure by many groups. He once wrote that it is "wiser to treat men and things as though we held this world the common fatherland of all." His ideas about everyone sharing the world are still important today.

Several schools and universities are named after him. These include Erasmus Hall High School in New York, USA.

Erasmus is known for saying, "When I get a little money I buy books; and if any is left, I buy food and clothes."

The European Erasmus Programme is named after him. This program helps students study in another European country.

Clothing Style

After leaving the monastery around 1517, Erasmus chose his own clothes. He liked warm, soft clothes. He wore a changed version of the Augustinian religious habit. He had it lined with fur to keep him warm. It had a fur collar that covered his neck. His hat was also unusual. It was padded at the back. This might have been because of the shape of his head. His skull was examined in 1928. His own writings and drawings also suggest this.

Personal Symbol and Motto

Erasmus chose the Roman god of borders, Terminus, as his personal symbol. He had a signet ring with a carving he thought was Terminus. His student Alexander Stewart gave him the ring in Rome. The carving was actually of the Greek god Dionysus. This ring was shown in a portrait of Erasmus by Quentin Matsys.

His personal motto was Concedo Nulli, which means "I concede to no-one." In the early 1530s, Hans Holbein the Younger painted Erasmus as Terminus.

Portraits of Erasmus

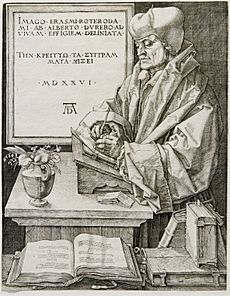

- Hans Holbein the Younger painted Erasmus at least three times in 1523. Erasmus used these portraits as gifts for friends. He spoke well of Holbein as an artist. But he later criticized him for seeking money more than art.

- Albrecht Dürer also made portraits of Erasmus. He met Erasmus three times. Dürer made an engraving in 1526. Erasmus was not impressed with it. He said it did not look like him. But Erasmus and Dürer were good friends. Dürer even asked Erasmus to support Luther. Erasmus politely said no. Erasmus wrote a glowing praise of Dürer. He compared him to a famous Greek painter. Erasmus was very sad when Dürer died in 1528.

- Quentin Matsys made the earliest known portraits of Erasmus. These included an oil painting in 1517 and a medal in 1519.

- In 1622, Hendrick de Keyser made a bronze statue of Erasmus. It replaced an older stone one from 1557. It is in the public square in Rotterdam. It is the oldest bronze statue in the Netherlands.

Works

- Adagia (1500)

- Enchiridion militis Christiani (1503)

- Stultitiae Laus (Praise of Folly (1511)

- De Utraque Verborum ac Rerum Copia (1512)

- Sileni Alcibiadis (1515)

- Novum Instrumentum omne (1516)

- Institutio principis Christiani (1516)

- Querela pacis (1517)

- Colloquia (1518)

- Lingua, Sive, De Linguae usu atque abusu Liber utillissimus ("Language, or the uses and abuses of language, a most useful book") (1525)

- Ciceronianus (1528)

- De recta Latini Graecique sermonis pronuntiatione (1528)

- De pueris statim ac liberaliter instituendis (1529)

- De civilitate morum puerilium (1530)

- Consultatio de Bello Turcis Inferendo (1530)

- De praeparatione ad mortem (1533)

- A Playne and Godly Exposition or Declaration of the Commune Crede (1533)

- Ecclesiastes (1535)

- De octo orationis partium constructione libellus (1536)

- Apophthegmatum opus (1539)

- The first tome or volume of the Paraphrase of Erasmus vpon the newe testamente (1548)

Images for kids

-

Erasmus censored by the Index Librorum Prohibitorum

See also

In Spanish: Erasmo de Róterdam para niños

In Spanish: Erasmo de Róterdam para niños

- Erasmus House, a museum in Anderlecht (Brussels) dedicated to the humanist's life and work

- Erasmus Student Network

- List of Erasmus's correspondents

- Mammotrectus super Bibliam

- Rodolphus Agricola

- Textus Receptus