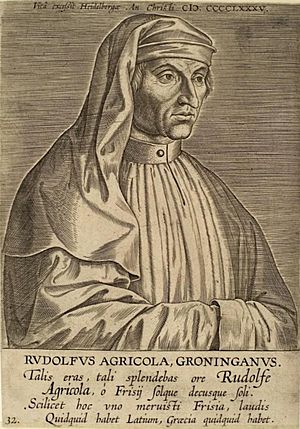

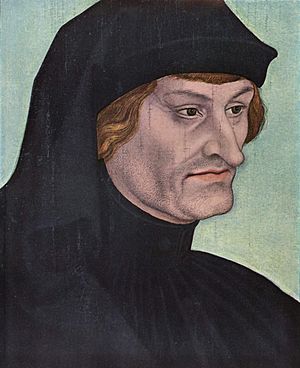

Rodolphus Agricola facts for kids

Rodolphus Agricola (born August 28, 1443, or February 17, 1444 – died October 27, 1485) was a famous Dutch humanist. He was known for his deep knowledge of Latin and Greek. Agricola was many things: an educator, a musician who built church organs, a poet, and even a boxer. Towards the end of his life, he also became a Hebrew scholar.

Today, he is best remembered for his book De inventione dialectica. He is also called the "father of Northern European humanism." He was a strong opponent of scholasticism, which was a way of thinking popular in universities during the late 1400s.

Contents

About Rodolphus Agricola

Rodolphus Agricola was born in Baflo, a place in the Dutch province of Groningen. His birth name was Roelof Huesman. The name Phrisius shows he was from Frisia.

He first went to school in Groningen. Then, he studied at the University of Erfurt and later at Louvain University. He earned his master's degree in 1465. People admired his perfect Latin and his skill in debates. He studied famous Roman writers like Cicero and Quintilian. He also learned French and Greek. Later in life, he learned Hebrew to read the Old Testament, especially the Psalms, in its original language.

Travels and Studies

In the 1460s, Agricola traveled to Italy. There, he met important humanist teachers and leaders. From about 1468 to 1475, he studied law at the University of Pavia. After that, he went to Ferrara (1475–1479). In Ferrara, he became a student of Theodor Gaza and attended lectures by Battista Guarino. He spent his time studying old classical texts. He became famous for his elegant Latin writing style and his knowledge of philosophy.

While in Ferrara, Agricola also worked as an organist for the duke's chapel. He held this job until 1479. Then, he returned north and became a secretary for the city of Groningen. He became a central figure among scholars and humanists. He exchanged many letters with people like the musician Jacobus Barbirianus and the scholar Johannes Reuchlin.

Teaching and Writing

In 1470, Agricola taught a deaf child how to speak and write. This was a very early and important effort in education for deaf people. His book, De inventione dialectica, talks about this work.

After returning to Germany, he spent time in Dillingen. He continued to write letters to his humanist friends across Europe. In these letters, he promoted the study of classical learning. Agricola chose to be an independent scholar. This meant he didn't work for a university or a religious group. This independence became a key feature of humanist scholars.

In 1479, Agricola finished his book De inventione dialectica (On Dialectical Invention). In this book, he explained how to use loci (common topics or points) precisely in scholarly arguments.

From 1480 to 1484, he worked as the secretary for the city of Groningen.

In 1481, Agricola spent six months in Brussels at the court of Archduke Maximilian. Friends tried to tell him not to accept the archduke's support. They worried it would change his philosophical ideas. He also turned down an offer to lead a Latin school in Antwerp.

In 1484, Agricola moved to Heidelberg because Johann Von Dalberg, the Bishop of Worms, invited him. They had met in Pavia and became close friends in Heidelberg. The bishop was very generous in supporting learning. At this time, Agricola started studying Hebrew. He is said to have published his own translation of the Psalms.

In 1485, Dalberg was sent as an ambassador to Pope Innocent VIII in Rome. Agricola went with him. On their journey, Agricola became very ill. He died shortly after they returned to Heidelberg.

Rodolphus Agricola's Impact

Agricola's book De inventione dialectica was very important. It helped make a place for logic in the study of rhetoric (the art of speaking or writing effectively). It was also significant for the education of early humanists. The book looked at ideas and concepts related to dialectics (the art of discussing and reasoning).

Agricola believed that people born deaf could express themselves by writing down their thoughts. His statement that deaf people can be taught a language is one of the earliest positive statements about deafness ever recorded.

Agricola's letter De formando studio was about a personal education program. It was printed as a small booklet and influenced how people taught in the early 1500s.

Agricola also had a big personal influence on others. Erasmus, a very famous scholar, admired Agricola greatly. Erasmus called him "the first to bring a breath of better literature from Italy." Erasmus saw him as a father or teacher figure. He might have met Agricola through his own teacher, Alexander Hegius, who was likely one of Agricola's students. Another student of Agricola was Conrad Celtis.

Erasmus made it his goal to make sure several of Agricola's important works were printed after his death.

Writings by Rodolphus Agricola

- Letters: Agricola's letters, with 51 still existing, show interesting details about the humanist group he belonged to.

- A Life of Petrarch (Vita Petrarcae / De vita Petrarchae, 1477)

- De nativitate Christi

- De formando studio (a letter to Jacobus Barbireau from 1484 about education)

- Other works: His smaller works include speeches, poems, translations of Greek dialogues, and comments on works by Seneca, Boethius, and Cicero.

See also

In Spanish: Rodolphus Agricola para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |