Anderton Boat Lift facts for kids

The Anderton Boat Lift is an amazing machine that helps boats move between two different waterways: the River Weaver and the Trent and Mersey Canal. It's located near the village of Anderton in Cheshire, North West England. This special lift acts like a giant elevator for boats, raising or lowering them about 50 feet (15 meters) – that's like a five-story building! It's so important and unique that it's known as one of the "Seven Wonders of the Waterways."

The lift was built way back in 1875 and worked for over 100 years. However, it had to close in 1983 because parts of it had rusted. After a big effort, restoration work began in 2001, and the lift was reopened in 2002. Today, the Canal & River Trust looks after the lift and its visitor center. It's one of only two working boat lifts in the United Kingdom, the other being the Falkirk Wheel in Scotland.

Contents

Why Was the Boat Lift Needed?

For a very long time, people in Cheshire have been digging up salt from underground. By the late 1600s, there was a huge salt mining business around towns like Northwich, Middlewich, and Winsford.

To move all this salt, the River Weaver was made easier for boats to travel on in 1734. This allowed salt to be transported from Winsford all the way to Frodsham, where the Weaver river meets the River Mersey. Later, in 1777, the Trent and Mersey Canal opened. This canal also ran close to the Weaver river for a while, but it stretched further south to areas with coal mines and pottery factories near Stoke-on-Trent.

Instead of competing, the owners of the river and the canal decided it would be better to work together. In 1793, they dug a special basin (a small harbor) on the River Weaver at Anderton. This basin brought the river right up to the foot of a steep hill where the canal was, about 50 feet higher! At first, workers had to unload goods from boats on one waterway and then load them onto boats on the other. They used cranes, salt chutes, and even a sloping ramp to move things.

How the Boat Lift Was Designed

By 1870, the Anderton Basin was a very busy place for moving goods between the river and the canal. But moving everything by hand was slow and costly. The people in charge of the Weaver Navigation decided they needed a direct link so boats could simply pass from one waterway to the other. They thought about building a series of locks, but that would have used too much water and there wasn't a good spot for them. So, in 1870, they suggested building a boat lift.

They asked their main engineer, Edward Leader Williams, to design the lift. He came up with a clever idea: two water-filled boxes, called caissons, that would balance each other. This way, it would take very little power to lift boats up and down. He decided to use powerful water-filled cylinders, called hydraulic rams, to support the caissons. These rams would be buried underground, meaning the structure above ground could be much lighter. He might have gotten this idea from seeing a similar lift in London.

Edwin Clark, an expert in hydraulic systems, was chosen as the main designer. The lift was built on a small island in the Anderton Basin. The caissons were made of strong iron and were about 75 feet (23 meters) long, 15 feet (4.7 meters) wide, and 9.5 feet (2.9 meters) deep. Each caisson could hold two narrowboats or one wider barge. When empty, a caisson weighed about 90 tons, but when full of water (with or without boats), it weighed about 252 tons.

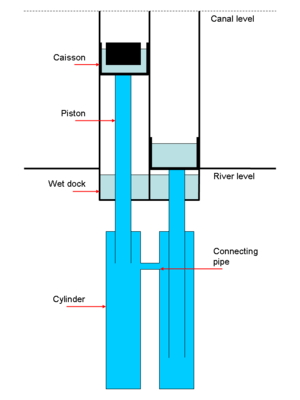

Each caisson was supported by a single hydraulic ram. This ram was a hollow iron piston, 50 feet (15 meters) long and 3 feet (0.9 meters) wide, sitting inside a buried iron cylinder. At the river level, the caissons rested in a water-filled chamber. Above ground, there were seven hollow iron columns that guided the caissons and supported a platform and stairs. At the top, the lift connected to the Trent and Mersey Canal through a 165-foot (50-meter) long iron bridge, called an aqueduct.

Normally, the two hydraulic cylinders were connected by a pipe. This allowed water to flow between them, so the heavier caisson would go down and push the lighter one up. To make small adjustments, or if only one caisson needed to move, a steam engine and a pressure tank at the top of the lift could power either ram on its own. This was slower, taking about 30 minutes instead of three minutes for a full lift.

Building the Lift

In October 1871, the Weaver Navigation Trustees decided to build the boat lift. In July 1872, the government officially approved the , which gave permission for the lift to be built.

Quick facts for kids Weaver Navigation Act 1872 |

|

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

|

|

| Long title | An Act to enable the Trustees of the River Weaver Navigation to make a Communication at Anderton between their Navigation and the Trent and Mersey Canal, and for other purposes with respect to the same Trust. |

| Citation | 35 & 36 Vict. c. xcviii |

The company Emmerson, Murgatroyd & Co. was hired to build it. Work began in late 1872 and took two and a half years. The Anderton Boat Lift officially opened on July 26, 1875. The total cost was about £48,428, which would be millions of pounds today!

Problems with the Hydraulic System

For five years, the boat lift worked well, only closing when the canal froze in cold weather. But in 1882, a big problem happened: one of the cast iron hydraulic cylinders burst while a caisson with a boat in it was at the top. The caisson dropped quickly, but the escaping water slowed it down, and the water at the bottom softened the landing. Luckily, no one was hurt, and the main structure wasn't damaged. As a safety check, they tested the other cylinder, and it also failed! The lift had to close for six months while new parts were installed and the pipes were redesigned.

Even after repairs, the hydraulic system continued to have issues. The main problem was that the pistons, which moved up and down, started to rust and get grooves in them. This happened because they used canal water in the system, and the pistons were always wet at river level. Attempts to fix the grooves with copper actually made the problem worse because of a chemical reaction with the slightly acidic canal water. In 1897, they switched to using distilled water (very pure water) to slow down the rust, but it didn't stop it completely. Over the next few years, the lift needed more and more repairs, sometimes closing completely or running slowly with only one caisson.

Changing to Electrical Power

By 1904, the Weaver Navigation Trustees knew they would have to close the lift for a long time to fix the hydraulic rams properly. They asked their Chief Engineer, Colonel J. A. Saner, to find a different way to power the lift.

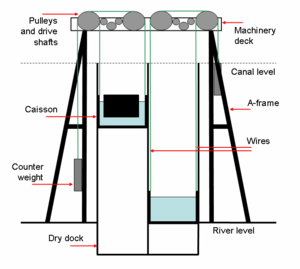

Saner suggested using electric motors and a system of counterweights and pulleys. This new system would allow each caisson to work on its own. Even though it had more moving parts, these parts would be above ground, making them easier and cheaper to fix. Saner also said it would need fewer workers and avoid expensive boiler repairs. He promised to make the change with only three short closures, which was important to keep traffic moving and avoid losing money.

With the new system, the weight of the caissons and counterweights would be held by the lift's main structure, not the underground rams. So, the structure was made much stronger and given new foundations. The new steel framework was built around the old one to avoid taking the lift out of service for too long. This new structure had ten large steel A-frames that supported a machinery deck 60 feet (18 meters) above the river. Here, electric motors, drive shafts, and large pulleys were installed. Strong wire ropes were attached to both sides of each caisson, went over the pulleys, and connected to 36 heavy cast iron counterweights. Each counterweight weighed 14 tons, and there were 18 on each side to balance the 252-ton weight of a loaded caisson. A 30-horsepower electric motor was installed, but it usually only needed about half that power to operate.

Besides the new structure, the wet dock at river level was turned into a dry dock, and the aqueduct connecting the lift to the canal was also made stronger. The original caissons were kept but changed to hold the new wire ropes.

The conversion happened between 1906 and 1908. Just as Saner promised, the lift was only closed for three short periods, totaling 49 days. The electrically powered lift officially opened on July 29, 1908.

How the Lift Worked After the Change

After being converted to electrical power, the boat lift worked successfully for 75 years. It still needed regular maintenance, especially replacing the wire ropes because they would get tired from bending over the pulleys. However, fixing things was much easier because all the machinery was above ground. It was also cheaper because the caissons could now run independently. This meant most repairs could be done while one caisson was still working, so the lift didn't have to close completely.

In the early 1940s, the old hydraulic rams, which had been left underground, were removed to reuse their iron. By the 1950s and 1960s, fewer commercial boats used British canals. By the 1970s, the lift was mostly used by pleasure boats and hardly at all in winter.

The new steel structure was prone to rust, so the entire lift was painted with a special protective solution every eight years. In 1983, during one of these repainting jobs, a lot of rust was found in the structure. It was declared unsafe and had to close.

Bringing the Lift Back to Life

In the 1990s, British Waterways started looking into how to restore the lift. At first, they planned to restore it to electrical operation. But after talking with English Heritage, they decided in 1997 to bring back the original hydraulic system, but using hydraulic oil instead of water.

To raise the £7 million needed for the restoration, many groups worked together, including the Waterways Trust and the Inland Waterways Association. The Heritage Lottery Fund gave £3.3 million, and over 2,000 people donated money, raising another £430,000.

Restoration began in 2000, and the lift reopened to boats in March 2002. Today, there's a two-story visitor center with a coffee shop and films about the lift's history. The visitor center also houses the new control room for the lift. Even though the original hydraulic system was brought back, the old steel frame and pulleys from the 1906-08 conversion were kept. They don't work anymore, but they are still part of the lift's look. The heavy counterweights that used to balance the caissons were not put back up; instead, they were used to build a maze in the visitor center's grounds!

More restoration work is planned to start in mid-2025 and will last for about 12 to 18 months. During this time, the lift will be closed.

Images for kids

See also

- List of Scheduled Monuments in Cheshire (post-1539)

- List of waterway societies in the United Kingdom

- Strépy-Thieu boat lift – the world's second-tallest boat lift, in Le Rœulx, province of Hainaut, Belgium

- Falkirk Wheel

- Peterborough lift lock – the world's tallest hydraulic boat lift, in Peterborough, Ontario, Canada

- Foxton Inclined Plane – former inclined plane on the Grand Union Canal

- Canals of the United Kingdom

- Canals in Cheshire

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |