History of the British canal system facts for kids

The canal network in the United Kingdom was super important during the Industrial Revolution. These canals helped Britain become rich and powerful, leading to the British Empire in the Victorian Era. The UK was the first country to build a huge network of canals, which grew to almost 4,000 miles (6,400 kilometres) long! Canals made it much faster and cheaper to move raw materials to factories. They also helped transport finished products to people who wanted to buy them. This was a big improvement over slow and expensive land travel.

Before canals, some rivers were made deeper for boats. The Exeter Ship Canal was finished in 1567. The Sankey Canal was the first important canal of the Industrial Revolution, opening in 1757. The Bridgewater Canal followed in 1761 and made a lot of money. The "Golden Age" of canals happened between the 1770s and 1830s. Most of the canal network was built during this time. After 1840, canals started to decline. This was because the new railway network was a faster way to move goods. By the 1900s, roads became more important. Canals became too expensive to use and were left empty. Because of this, in 1948, the government took over many canals. Since the late 1900s, canals have become popular again for fun activities and tourism.

Different kinds of boats used the canals. The most common was the traditional narrowboat. These boats were often painted with special "Roses and Castles" designs. At first, horses pulled the boats. Later, boats used diesel engines. Today, people are working to fix up old canals. There are also museums about canals. The canal network was huge and included amazing engineering feats. Some examples are the Anderton Boat Lift, the Manchester Ship Canal, the Worsley Navigable Levels and the Pontcysyllte Aqueduct.

Contents

History of Canals in the UK

Early Waterways and Why Canals Were Needed

After the Middle Ages, some natural rivers were improved for boats. This happened in the 1500s. For example, the city of Canterbury got permission in 1515 to make the River Stour easier to navigate. In 1539, the River Exe was improved, leading to the Exeter Ship Canal in 1566. Simple flash locks were used to control water flow. These allowed boats to pass through shallow areas by releasing a rush of water. However, these were not like the canals we know today.

Before canals, people moved goods using ships along the coast. They also used horses and carts on muddy roads. Most roads were not paved and became unusable after heavy rain. Only a small amount of goods moved on rivers. In the 1600s, as industries grew, this transport system was not good enough. Horses and carts could only carry one or two tons of cargo at a time. This made important goods like coal and iron ore expensive. It also slowed down economic growth. One canal boat pulled by a horse could carry about thirty tonnes. This was much faster than roads and cost half as much.

About 29 river improvements happened in the 1500s and 1600s. In 1605, King James I's government started to improve the locks and weirs on the River Thames. By 1635, boats could travel between Oxford and Abingdon. In 1635, Sir Richard Weston worked on the River Wey Navigation. This made Guildford reachable by boat by 1653. The Stamford Canal opened in 1670. It looked just like canals built in the 1700s, with a special cut and double-door locks.

By the early 1700s, river navigations like the Aire and Calder Navigation were becoming very advanced. They had pound locks and longer "cuts." Cuts were new channels built to avoid difficult parts of rivers. Building these long, multi-level cuts with their own locks gave people an idea. Why not build a "pure" canal? This would be a waterway designed exactly where goods needed to go, not just where a river happened to be.

Canals and the Industrial Revolution

The UK was the first country to build a nationwide canal network. Canals changed Britain's economy a lot. They helped industries grow, making Britain the world's first industrial power. This created wealth that led to the British Empire in the Victorian Era. Canals were built because they were the cheapest and most reliable way to move large amounts of goods. The network of waterways grew quickly and became almost fully connected. New canals were built, and old ones were improved. They got new embankments, tunnels, aqueducts, and cuttings. However, people often strongly opposed building them.

The Sankey Canal was the first British canal of the Industrial Revolution. It opened in 1757. It connected St Helens with Spike Island in Widnes. This canal helped the chemical industry grow in Widnes. Widnes then became a major center for this industry in England. In the mid-1700s, the 3rd Duke of Bridgewater built the Bridgewater Canal. He wanted to move coal from his mines to the growing city of Manchester. He hired engineer James Brindley to build the canal. The design included an aqueduct that carried the canal over the River Irwell. This aqueduct was an amazing engineering feat and attracted tourists.

The Duke paid for the Bridgewater Canal himself. It opened in 1761 and was the longest canal built in Britain at that time. Canal boats could carry thirty tons at once. One horse could pull more than ten times the amount of cargo a cart could carry. The Bridgewater Canal cut the price of coal in Manchester by almost two-thirds within a year. The canal was a huge financial success. It paid back its building cost in just a few years.

The 1800s saw some big new canals like the Caledonian Canal and the Manchester Ship Canal. These new canals were very successful. Horses pulled the boats on the canals. There was a special path called a towpath alongside the canal for the horse to walk on. This horse-drawn system was very cheap and became standard across the British canal network. Commercial horse-drawn canal boats were used in the UK until the 1950s. By then, diesel-powered boats, often pulling a second unpowered boat, were common. In the late 1800s, the "Roses and Castles" boat decoration started to appear. During this time, whole families lived on the boats.

The "Golden Age" of Canals

The time between the 1770s and the 1830s is called the "Golden Age" of British canals. During this period of "canal mania," huge amounts of money were invested in building canals. The canal system grew to almost 4,000 miles (6,400 kilometres) long.

At the start of this age, groups of private individuals built canals. They wanted to improve transport. In Staffordshire, the potter Josiah Wedgwood saw a chance to bring heavy clay to his factory. He also wanted to reduce how many of his fragile finished goods broke on the way to market. In just a few years, a basic national canal network began to form.

Acts of Parliament were needed to allow construction. Financial investors proposed canals, hoping to make money. Industrial businesses also wanted to move their raw materials and finished goods. There was often a lot of financial speculation. People would buy shares in new canal companies, hoping to sell them for a profit. They didn't care if the canal ever made money or was even built. Rival canal companies were formed, and competition was fierce. For many years, a disagreement about tolls meant goods traveling through Birmingham had to be moved from boats in one canal to boats in another.

On most British canals, the companies that owned the canals did not own or run boats. The laws that set them up usually prevented this. This was to stop one company from having a monopoly. Instead, they charged private operators tolls to use the canal. These tolls were controlled by the laws. From the tolls, the owners tried to maintain the canal, pay back loans, and pay money to their shareholders.

Canals Face Railway Competition

Around 1840, the railway network became more important. Trains could carry more goods and people. They were also much faster than the walking pace of canal boats. Most of the money that used to go into building canals now went into building railways. By the late 1800s, many canals were owned by railway companies or were competing with them. Many canals were declining. They lowered their prices to try to stay competitive. After this, the less successful canals, especially narrow ones that could only carry about thirty tons, failed quickly.

Canal companies could not compete with the speed of the new railways. To survive, they had to cut their prices. This ended the huge profits canal companies had made before railways. It also affected the boatmen, who faced lower wages. Fast "flyboat" services almost stopped. They couldn't compete with railways on speed. Boatmen found they could only afford to keep their families by taking them on the boats. This became normal practice. Families with several children often lived in tiny boat cabins. This created a large community of boat people.

By the 1850s, the railway system was well-established. The amount of cargo carried on canals had dropped by almost two-thirds. Most of this cargo was lost to railway competition. In many cases, struggling canal companies were bought by railway companies. Sometimes, this was a smart move by railways to gain control in their rivals' areas. But sometimes, canal companies were bought just to close them down and remove competition. Or, a railway might be built along the canal's path. The Croydon Canal is a good example of this. Larger canal companies survived independently and continued to make money. Canals survived through the 1800s by finding special jobs the railways missed. They also supplied local markets, like factories in big cities that needed coal.

In the 1800s, many countries in Europe, like France and Germany, made their canal systems wider for much larger boats. This modernization didn't happen much in the UK. This was mainly because railway companies owned most canals. They saw no reason to invest in a competing type of transport. The only big exception was the Grand Union Canal, which was modernized in the 1930s. So, unlike most of Europe, many UK canals are still like they were in the 1700s and 1800s. They mostly use narrowboats. The Manchester Ship Canal was an exception. It was newly built in the 1890s using the River Irwell and River Mersey. It allowed ocean-going ships to reach the center of Manchester.

Road Competition and Nationalization

The 1900s brought competition from road transport. The canal network declined even more. In the 1920s and 1930s, many canals in rural areas were abandoned. This was because there was less traffic. The main canal network saw short increases in use during World War I and World War II. Most of the canal system was taken over by the government in 1948. It came under the control of the British Transport Commission. Their group, the Docks and Inland Waterways Executive, managed them into the 1950s. A report in 1955 put canals into three groups: those to be developed, those to be kept, and those not worth keeping for business.

In the 1950s and 1960s, freight transport on canals quickly declined. This was due to the rise of mass road transport. Coal was still delivered to factories by water if they had no other easy access. But many factories that used coal switched to other fuels. This was often because of the Clean Air Act 1956. Or, they closed completely. Under the Transport Act of 1962, canals were moved to the British Waterways Board (BWB) in 1963. This later became British Waterways. In the same year, the BWB decided to stop most of its narrowboat operations. They transferred them to a private company. By this time, the canal network had shrunk to 2,000 miles (3,000 kilometres). This was half its size at its peak in the early 1800s. However, the basic network was still there. Many closures were of duplicate routes or branches. By the mid-1960s, only a tiny amount of commercial traffic was left.

The Transport Act 1968 said the British Waterways Board must keep commercial waterways fit for business. It also said cruising waterways must be fit for cruising. But these rules had a catch: it had to be done in the cheapest way. There was no rule to keep them in a condition for boats. They were to be treated in the most economic way possible, which could mean abandoning them. British Waterways could also change how a waterway was classified. All or part of the canals could be given to local authorities. This allowed roads to be built over them, avoiding expensive bridges. The last regular long-distance narrowboat commercial contract ended in 1971. This was for a jam factory near London. Lime juice was carried until 1981. Large amounts of aggregates were carried on the Grand Union Canal until 1996.

Canals for Fun and Recreation

In 1946, a group called the Inland Waterways Association was started by L. T. C. Rolt and Robert Aickman. This group helped people become interested in UK canals again. Now, canals are a major place for leisure activities. In the 1960s, the new canal leisure industry was just enough to stop the remaining canals from closing. Then, the demand to keep canals for fun increased. Even if they weren't used for business or leisure, many canals survived. This was because they were part of local water supply and drainage systems. From the 1970s, volunteers started to restore more and more closed canals.

The Canal & River Trust keeps a list of what it thinks are the most important canal sites. It's called the Seven Wonders of the Waterways. This list includes:

- Standedge Tunnel, the longest, deepest, and highest canal tunnel in the UK.

- The Caen Hill Flight of locks, one of the longest continuous lock flights.

- Barton Swing Aqueduct, the world's only swinging aqueduct, on the Bridgewater Canal.

- The Anderton Boat Lift, the world's first successful boat lift and the only one in the UK.

- Bingley Five Rise Locks, a staircase lock that is the steepest in the country.

- Burnley Embankment, a clever way to cross a wide valley with a canal.

- The Pontcysyllte Aqueduct, the longest and highest aqueduct in the UK.

Canals and the Slave Trade

The Canal and River Trust says that canals were partly built using money from the human slavery trade. Canals regularly carried goods like cotton, tobacco, and sugar that were produced by enslaved people. Many individuals made money from slavery. For example, Moses Benson, a slave trader from Liverpool, invested in the Lancaster Canal. This canal then had a big effect on the economy of Preston.

Other people involved in the slave trade, like Lowbridge Bright, were on the board of the Thames and Severn Canal Company. George Hyde Dyke owned shares in the Peak Forest Canal Company. William Carey owned shares in the Grand Junction Canal.

How Canals Were Built and What They Include

Locks are the most common way to move a boat up or down between different water levels. A lock is a special chamber where the water level can be changed. Early canals were built narrow to save money and because of the engineering limits in the 1700s. James Brindley set the standard for narrow canal locks with his first locks on the Trent and Mersey Canal in 1776. These locks were about 72 feet 7 inches (22.1 meters) long and 7 feet 6 inches (2.3 meters) wide. The narrow width might have been because his Harecastle Tunnel could only fit boats 7 feet (2.1 meters) wide. His next locks were wider. He built locks 72 feet 7 inches (22.1 meters) long by 15 feet (4.6 meters) wide when he extended the Bridgewater Canal to Runcorn. There, the canal's only locks lowered boats to the River Mersey.

The narrow locks on the Trent and Mersey limited the width of the boats (which became known as narrowboats). This also limited how much cargo they could carry, to about thirty tonnes. This decision later made the canal network less competitive for moving goods. By the mid-1900s, it was no longer profitable to move a thirty-tonne load.

Where there is a big height difference, locks are built close together in a flight. An example is at Caen Hill Locks. If the slope is very steep, a set of staircase locks might be used, like Bingley Five Rise Locks. At the other extreme, stop locks have little or no change in level. They were built to save water where one canal joined another. An interesting example is King's Norton Stop Lock, which had special guillotine gates.

Canal aqueducts are structures that carry a canal over a valley, road, railway, or another canal. Dundas Aqueduct is made of stone in a classic style. Pontcysyllte Aqueduct is an iron trough on tall stone pillars. Barton Swing Aqueduct opens to let ships pass underneath on the Manchester Ship Canal. Three Bridges, London is a clever design that lets the Grand Junction Canal, a road, and a railway line cross each other.

Boat lifts are machines that raise a canal boat straight up in one go. This is different from using a series of locks. Examples include the Anderton Boat Lift, Falkirk Wheel, and Combe Hay Caisson Lock. Inclined planes lift a canal boat up a hill on a track. They are powered by a pulley system. Examples include the Hay Inclined Plane, Foxton Inclined Plane, and Worsley Underground Incline. Tunnels take canal boats horizontally through rock. In winter, special icebreaker boats with strong hulls would break the ice.

Some of the engineers who designed and built the canals were Henry Berry, James Brindley, William Jessop, Thomas Telford, and John Rennie the Elder.

Canal Boats

The boats used on canals usually came from local coastal or river boats. But on the narrow canals, the 7-foot (2.1-meter) wide narrowboat was the standard. Their 72-foot (21.9-meter) length came from boats used on the Mersey estuary. Their width of 7 feet (2.1 meters) was chosen as half the width of existing boats. Packet boats carried packages up to 112 pounds (51 kg) and passengers. They traveled relatively fast, day and night. To compete with railways, "flyboats" were introduced. These were cargo boats that worked day and night. Three men crewed these boats. They worked in shifts, so two men worked while one slept. Horses were changed regularly. When steam boats were introduced in the late 1800s, crews grew to four. Individual carriers or carrying companies owned and operated the boats. They paid the captain based on the distance traveled and the amount of cargo.

Many different types of boats were used on the canals. They include: Cabin Cruisers, Fly-boats, Humber Keels, Mersey Flats, Narrowboats, Trows, Sloops, and Tub boats.

Bringing Canals Back to Life: Restoration

Waterway restoration groups have brought hundreds of miles of abandoned canals back into use. Work is still ongoing to save many more. Many restoration projects have been led by local canal groups. These groups first formed to fight the closure of a waterway or to save an abandoned canal from falling apart. Now, they work with local governments and landowners. They develop restoration plans and get money for them. The physical work is sometimes done by contractors. Other times, volunteers do the work. In 1970, the Waterway Recovery Group was formed. It helps organize volunteer efforts on canals and rivers across the UK.

British Waterways started to see the economic and social benefits of developing areas along canals. They changed from being against restoration to being neutral, then supportive. While British Waterways generally supported restoration, their official rule was that they would not take on new restored waterways unless they came with enough money to pay for their ongoing care. This meant either reclassifying the waterway or having another group agree to maintain it. Today, most canals in England and Wales are managed by the Canal & River Trust. Unlike its predecessor, British Waterways, this trust has a more positive view of canal restoration. In some cases, it actively supports ongoing restoration projects. Examples include the Manchester Bolton & Bury Canal and the Grantham Canal.

There has also been a movement to redevelop canals in inner-city areas. Cities like Birmingham, Manchester, Salford, and Sheffield have many waterways and old, run-down areas. In these cities, waterway redevelopment helps create successful business and housing projects. Examples include Gas Street Basin in Birmingham, Castlefield Basin and Salford Quays in Manchester, and Victoria Quays in Sheffield. However, these developments are sometimes debated. In 2005, environmentalists complained that new housing along London's waterways threatened the canal system's lively atmosphere.

Volunteer groups continue to work on restoration projects. Now, there is a large network of connected, fully navigable canals across the country. In some places, the Environment Agency and the Canal & River Trust have serious plans to build new canals. These plans aim to expand the network, connect isolated sections, and create new opportunities for leisure boating. Examples include the Fens Waterways Link and the Bedford and Milton Keynes Waterway. The Rochdale Canal, the Huddersfield Narrow Canal, and the Droitwich Canals have all been restored for navigation since 2000.

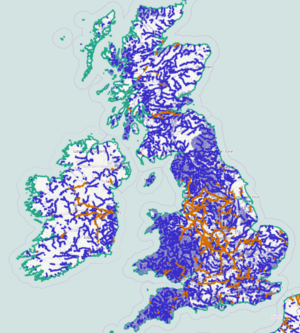

Where Canals Are Located

Most of the canal system was built in the industrial Midlands and the north of England. This is where rivers most needed extending and connecting. It's also where heavy goods like manufactured products, raw materials, or coal most needed to be moved. The big manufacturing cities of Manchester and Birmingham were major economic drivers. Most of the traffic on the canal network was within the country. However, the network connected with coastal port cities like London, Liverpool, and Bristol. Here, cargo could be traded with seagoing ships for import and export. In the 1800s, Manchester's merchants were unhappy with the poor service and high prices from Liverpool docks. They also disliked the railways' near-monopoly. They decided to bypass Liverpool by turning a section of the Irwell into the Manchester Ship Canal. This opened in 1894, making Manchester its own inland port.

The Industrial Revolution saw Yorkshire towns and cities like Leeds, Sheffield, and Bradford develop large textile and coal mining industries. These needed an efficient transport system. As early as the late 1600s, the Aire and Calder and Calder and Hebble navigations were made into canals. This allowed boats to travel from Leeds to the Humber Estuary. The River Don Navigation connected Sheffield to the Humber. Later in the 1700s, the Leeds and Liverpool Canal was built. This created an east-west link, giving access to the port at Liverpool for exporting finished goods.

London is a port city. As early as 1790, London was linked to the national network through the River Thames and the Oxford Canal. A more direct route between London and the national canal network, the Grand Junction Canal, opened in 1805. Relatively few canals were built in London itself.

The South West of England had several east-west canals. These connected the River Thames to the River Severn and the River Avon. This allowed the cities of Bristol and Bath to be connected to London. These canals were the Thames and Severn Canal (which linked to the Stroudwater Navigation), the Kennet and Avon Canal, and the Wilts and Berks Canal. These linked to the three rivers.

In Scotland, the Forth and Clyde Canal and the Union Canal connected the major cities in the industrial Central Belt. They also provided a shortcut for boats to cross between the west and east without a sea journey. The Caledonian Canal did a similar job in the Highlands of Scotland.

Canal Museums to Visit

- National Waterways Museum, Ellesmere Port, Cheshire

- Foxton Canal Museum, Harborough, Leicestershire

- Galton Valley Canal Heritage Centre, Smethwick, West Midlands

- Gloucester Waterways Museum, Gloucestershire

- Kennet & Avon Canal Museum, Devizes, Wiltshire

- Linlithgow Canal Centre, Scotland

- Llangollen Canal Museum, North Wales

- London Canal Museum, Kings Cross, London

- Portland Basin Museum, Manchester

- Stoke Bruerne Canal Museum, Northamptonshire

- Tapton Lock Visitor Centre, Chesterfield

- Yorkshire Waterways Museum, Goole, East Yorkshire