Stroudwater Navigation facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Stroudwater Navigation |

|

|---|---|

Nutshell Bridge on the Stroudwater Navigation

|

|

| Specifications | |

| Maximum boat length | 70 ft 0 in (21.34 m) |

| Maximum boat beam | 15 ft 6 in (4.72 m) |

| Locks | 12 |

| Status | Active restoration project |

| History | |

| Original owner | Proprietors of the Stroudwater Navigation |

| Principal engineer | John Priddy, Edmund Lingard |

| Date of act | 1730, 1776 |

| Date completed | 1779 |

| Date closed | 1954 |

| Geography | |

| Start point | Wallbridge, near Stroud |

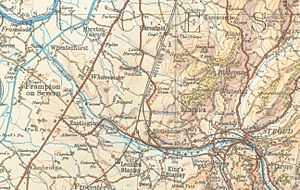

| End point | Framilode, River Severn |

| Connects to | River Severn, Thames and Severn Canal |

The Stroudwater Navigation is a special waterway, or canal, in England. It was built to connect the town of Stroud to the River Severn. This canal was officially approved in 1776. However, some parts were already built because people thought an older law from 1730 allowed them to start.

The canal opened in 1779 and quickly became a big success for trade. Its main job was to carry coal. It was about 8 miles (13 km) long. Boats had to go up 102 feet (31 meters) using 12 locks. Locks are like water elevators that help boats move between different water levels.

In 1789, the Thames and Severn Canal opened. This meant the Stroudwater Navigation became part of a long route from Bristol to London. But in 1810, the Kennet and Avon Canal offered a shorter way. This made some of the Stroudwater's trade disappear. Even with new railways, the canal kept making money for its owners until 1922. It was finally closed in 1954.

Even before it closed, people wanted to keep the canal for fun and beauty. The Stroudwater Canal Society started in 1972. This group later became the Cotswold Canals Trust. At first, the canal owners were not happy about this. But they eventually agreed, and work began to bring the waterway back to life.

The project became very popular. In 2003, a big request for £82 million was made. This money was for restoring both the Stroudwater Navigation and the Thames and Severn Canal. The project was too big for one go. So, it was split into smaller parts. The first part received £11.9 million in 2006. This money helped reopen the section from 'The Ocean' at Stonehouse to Wallbridge. It also reopened the Wallbridge to Hope Mill part of the Thames and Severn.

A second request for funding was made in 2007. This was for connecting Stonehouse to the Gloucester and Sharpness Canal at Saul. But this request was turned down. This section is tricky to restore. The M5 motorway and the A38 road were built over parts of it. For example, a roundabout was built over Bristol Road Lock. Also, flood control work for the River Frome destroyed some of the route.

In 2019, the Heritage Lottery Fund gave another £8.9 million for the section from Ocean to Saul. Highways England also gave £4 million. This money will help build the canal under the A38 roundabout. People expect the Stroud section to connect to the main canal network by late 2023. The Cotswold Canals Trust is also working to restore other parts of the canal. Their big goal is to link the River Thames and the River Severn again.

Contents

History of the Canal

Building the Stroudwater Canal

People first thought about making the River Frome (also called the Stroudwater) easier for boats to use in the late 1600s. The idea was to help the woollen industry. They wanted to bring coal from the Severn to Stroud. They also wanted to send finished cloth to markets. But mill owners did not like the idea, so nothing happened.

The idea came back in 1728. John Hore, who had made the River Kennet navigable, suggested a canal. It would be about 8.2 miles (13.2 km) long with 12 locks. It would be big enough for 60-ton boats. A law was passed in 1730 to allow this. Cloth workers supported it, but some millers were still against it. The law seemed to ignore Hore's ideas. It was still about making the river navigable. Millers were given powers that could close the canal for two months each year. Also, the fees for using the canal were too high. So, no more work was done.

In 1754, a new plan was made by engineer Thomas Yeoman. His plan was for a canal from Wallbridge to the Severn. It would cost about £8,145 and need 16 locks. To keep the millers happy, water for the locks would come from a reservoir. This reservoir would fill on Sundays when the mills were not using water. The fees were also set at a better level.

Another idea came up in 1759. It used cranes at each mill weir to move cargo in boxes from one boat to another. A new law was passed in 1759. It allowed this crane system to avoid building locks. This was to save water for the mills. They had two years to finish, but it was too expensive. After about 5 miles (8 km) of river were improved, the work stopped.

By 1774, people understood canal building much better. A new attempt was made. This time, the plan was led by William Dallaway. Engineers Thomas Dadford Jr. and John Priddy surveyed the route. They estimated a canal that avoided the river would cost £16,750. Soon, £20,000 was raised. They thought the 1730 law was still valid. So, they asked Yeoman to survey the route again. A route with 12 locks was chosen.

Work began with Samuel Jones as engineer, but John Priddy soon took over. Landowners and millers challenged the work in 1775. A court ruled that the 1730 law did not cover the new work. So, a new law was passed on March 25, 1776. This law allowed them to raise £20,000, plus an extra £10,000 if needed.

Work started again with Priddy, but then Edmund Lingard became the engineer. The canal opened in parts as it was finished. It reached Chippenham Platt in late 1777. It got to Ryeford in January 1779. The whole canal opened to Wallbridge on July 21, 1779. It cost £40,930 in total. This money came from shares, loans, and fees from the parts of the canal already open. About 16,000 tons of goods were carried each year. This helped the company pay off its debts. In 1786, they paid their first profit share to owners.

How the Canal Worked

The locks were built for Severn Trows. These boats were about 72 feet (22 m) long and 15.5 feet (4.7 m) wide. They could carry 60 tons of goods. The canal did not have a special path for horses to pull boats. Some boats sailed, but most were pulled by men.

Framilode lock at the canal's entrance was a tide lock. It had many gates to handle different tide levels. When a boat arrived, a rope was used with a capstan (a turning post) to pull the boat into the lock. After the canal opened, the owners worked to make things better. Many warehouses were built.

Many owners also helped with the Thames and Severn Canal project. This canal was finished in 1789. It created a direct route between Wallbridge and the River Thames at Lechlade. The Stroudwater Navigation was mainly for business. Pleasure boats were not encouraged. They had to pay £1 (a lot of money back then) for each lock they used.

Coal was the main cargo. In 1788, some owners started a coal business. At first, coal came from Staffordshire or Shropshire. Later, it came from south Gloucestershire and the Forest of Dean. This business was very profitable until 1833. Boats like Severn Trows, which were sailing boats, worked on the canal. Many were later changed into barges by removing their masts.

In 1794, a basin was built above Framilode lock. Boats could wait there for the right tide in the Severn. The Thames and Severn Canal company asked for a horse towpath in 1799 and 1812. But this was seen as too expensive. They finally built one after the Gloucester and Sharpness Canal was built. The Stroudwater was the only part of the waterway from Shrewsbury to Teddington without a towpath. It was finished in August 1827.

When the Gloucester and Berkeley Canal opened in 1825, it crossed the Stroudwater at Saul. A new lock was built on the Stroudwater to make sure neither company lost water. The new company paid for this lock. After the Gloucester and Berkeley Canal opened to Sharpness in 1827, the link between Saul and Framilode was used less. But coal from the Forest of Dean still used that route.

Traffic, money earned, and profits steadily grew. Fees rose from £1,468 in 1779 to £6,807 in 1821. The first profit share was 3.75 percent in 1786. It reached 15.78 percent by 1821. In 1821, 79,359 tons of goods were carried.

There was a small drop in trade in 1810. This was when the Kennet and Avon Canal opened. It offered a more convenient route from Bristol to London. But trade picked up again after 1819. This was when the North Wilts Canal opened. It provided an easier link from Latton to Abingdon. The highest profit share was in 1833, at 26.33 percent. After that, money earned and profits slowly dropped. In 1859, two locks were made wider for a coal boat called the Queen Esther.

The Canal's Decline

The first railway threat came in 1825. There was a plan for a railway from Framilode Passage to Brimscombe Port. The canal owners lowered their fees to try and stop it. But the railway builders went ahead. The Stroudwater Company fought against it, and the railway plan was defeated in Parliament.

The Great Western Railway opened a line from Swindon to Gloucester in 1845. This line went through Stroud. It affected the Stroudwater Canal less than it affected the Thames and Severn. However, in 1863, the Stonehouse and Nailsworth Railway Act was passed. This allowed a railway to be built from Stonehouse to Dudbridge and Nailsworth. This railway directly competed with the canal.

Profits for the canal fell below 5 percent after 1880. But they did not stop completely until 1922. Around the same time, the connection to the Severn at Framilode became blocked. This left the connection to the Gloucester and Sharpness Canal as the only link to the River Severn. The last fee was paid in 1941. Most of the canal was officially closed by a law passed in 1954.

Even though the canal closed, the Company of Proprietors (the original owners) still existed. They kept most of their powers. Today, it includes those who own the original shares. More than half of the shares were moved to a Trust in the 1950s. This helps make sure the company always works for the good of the communities along the canal. After closing, the canal company still made money for many years. They sold water and earned money from their properties.

Bringing the Canal Back to Life

People wanted to keep the canal for fun even before it closed. The Inland Waterways Association started a campaign in 1952 to save it. They were already planning to bring back the Thames and Severn Canal. This canal needed the Stroudwater to connect to the River Severn. In 1954, the National Parks Commission said the canal should be kept for its beauty. But it closed anyway.

In 1972, a book called Lost Canals of England and Wales was published. This book led to many canal restoration groups forming. It talked about 78 old canals and suggested restoring the Stroudwater and Thames and Severn Canals. In 1974, the BBC interviewed a local person, Michael Ayland. He suggested restoring the waterway. A newspaper article then appeared, saying "Exclusive: canal to be reopened to Stroud." Many people offered to help. An early public meeting had to be moved to a bigger room because so many people showed up. About 300 people met, and The Stroudwater Canal Society was formed.

This group changed its name to the Stroudwater, Thames and Severn Canal Trust in 1975. This was because their plans grew bigger. In 1990, it became the Cotswold Canals Trust. At first, the original canal owners were not friendly to the Trust. But this slowly changed. In 1979, they allowed the Trust to start work on a section from Pike Bridge to Ryeford. This meant a trip-boat could be used there. As attitudes improved, the owners even bought back parts of the waterway that had been sold.

How Restoration is Funded

In 2001, the Cotswold Canals Partnership was created. This group brought together the original owners, the Cotswold Canals Trust, local councils, and other interested groups. This helped push the restoration forward. In 2002, the canal was named a top priority for restoration in a report. It was also highlighted at a conference in March. The estimated cost to restore both the Stroudwater Navigation and the Thames and Severn Canal was £82 million.

The Cotswold Canals Trust raised £100,000. They put this money with the Waterways Trust. They hoped it could be used to get matching funds for grants. Andy Stumpf became the full-time manager for the project. He worked on a big request to the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF) for money. Charles, Prince of Wales (now King Charles III) visited the canal. He was a supporter of the Waterways Trust.

Surveys and plans were made, costing a lot of money. These were needed for the HLF request. By late 2003, the HLF was under pressure for funds. They asked British Waterways, who led the application, to split the project into smaller parts. At the end of 2003, a first grant of £11.3 million was given by the HLF. This was to restore the Stroudwater Navigation between Stonehouse and Wallbridge. It also covered the Thames and Severn Canal between Wallbridge and Brimscombe Port. An extra £2.9 million came from a European fund for this first part. When the grant was officially given in January 2006, it had grown to £11.9 million. Another £6 million in matching funds came from a regional agency.

In 2005, the original owners leased the canal to British Waterways. But British Waterways had money problems and left the project in 2008. Stroud District Council then took over leading the project. After this change, the Stroud Valleys Canal Company was set up in March 2009. This company holds the canal's assets. Because it is a charity, it does not have to pay certain taxes. This company will manage and maintain the canal once it reopens.

In 2013, Stroud District Council asked for £1.5 million from a new transport board. This money was to replace the Ocean railway culvert with a bridge. They also asked for £650,000 to create part of the Thames and Severn Way footpath. But these requests were not successful.

The effort to connect the restored section to the main canal network at Saul Junction was called Stroudwater Navigation Connected. Another request was made to the Heritage Lottery Fund. This was partly successful. They received £842,800 to plan the project. This money paid for surveys and detailed planning. It also helped get approval from the Environment Agency. If this work showed the project was possible and the costs were real, another £9 million would be given in early 2020.

The Connected Project

The second part of the restoration, called Phase 1b, was for the section from Stonehouse to the Gloucester and Sharpness Canal at Saul. This part was blocked by both the M5 motorway and the A38 road. A request for £16 million was made in August 2006. They received £250,000 to develop the plan, but the main request was rejected in November 2007. Even with this setback, money to buy land around the M5 and A38 was part of the first grant.

Current plans for the A38 involve building a tunnel under the Whitminster roundabout. The Bristol Road Lock was buried by the roundabout. A new lock will be built east of it. There are two ideas for going under the M5 motorway. One is a new channel next to the River Frome through an existing tunnel. The other is a new, wider tunnel closer to the canal's original path. Below this, the canal used to cross the Frome at Lockham Aqueduct. But this was taken down in the 1970s. The canal and river channel were combined for flood control.

Earlier requests for Heritage Lottery funding were rejected in 2012 and 2015. A new request was made in November 2017. This time, it had strong support. Stroud District Council promised £3 million. Gloucestershire County Council promised £700,000. The Canal & River Trust promised £675,000 and practical help. The Cotswold Canals Trust also offered money and volunteer help. Their volunteers work about 15,000 hours a year. They started clearing the channel and doing surveys on the Phase 1b section in early 2017. This was before any funding was available.

By 2017, the restoration of the section from Stonehouse to Stroud had brought in about £117 million of private money. This money was invested along the canal since work started in 2006. Also, another £3 million is being invested in improvements at Brimscombe Port. This was the original end point for the first part of the project.

In early 2016, work began on a £210,000 project to restore Junction Lock at Saul. This was thanks to a £75,000 grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund. The lock was not made usable for boats. But new lock gates were put in, and signs were added. Access to the area was also improved. The lock was on a list of "Buildings at Risk" before the work began.

By 2018, Phase 1b was renamed the Cotswold Canal Connected project. This is because it will connect the restored section to the main canal network at Saul Junction. The Cotswold Canal Trust received £872,000 in 2018 from the Heritage Lottery Fund. This money was for planning the project, which was estimated to cost about £23.4 million. The Heritage Lottery Fund was ready to give a large part of this. But the Trust needed to raise an extra £1 million to cover a gap in the total funding.

The Connected project includes bringing back the missing mile of canal. This part was destroyed by the M5 motorway and the A38 roundabout. The roundabout buried Bristol Road Lock. In a surprise move, Highways England agreed to help pay for this part of the work. This will involve two tunnels, a large cut in the ground, and two new locks. Their contribution of £4 million helped speed up the project. This money came from a special fund to leave a positive legacy. It will also fund about 90 acres (36 ha) of wildlife habitats. This will increase different types of plants and animals. It will also improve flood protection and create routes for cycling and walking.

Progress was fast. By late 2020, the channel under the roundabout was built and filled with water. The final steps of putting the roundabout back were well underway. The next big project was the railway embankment at Ocean. With an £8.9 million grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund and other money, this was expected to be replaced by a bridge in May 2021. The whole Connected project, which includes restoring eight more locks and a road bridge near Saul Junction, is expected to be finished by late 2023. By early 2021, a large area was set up near the railway bridge. Here, concrete parts for the bridge were being made.

Later checks of the ground showed that the bridge would need deeper foundations than first thought. So, the bridge replacement was moved to between Christmas 2021 and New Year.

Canal Connections

The Stroudwater Navigation connected to two other important canals:

- The Thames and Severn Canal at Wallbridge.

- The Gloucester and Sharpness Canal at Saul.

Places of Interest

| Point | Coordinates (Links to map resources) |

OS Grid Ref | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Framilode Junction with River Severn | 51°47′33″N 2°21′42″W / 51.7925°N 2.3616°W | SO751104 | |

| Jn with Gloucester and Sharpness Canal | 51°46′56″N 2°21′16″W / 51.7821°N 2.3545°W | SO756093 | |

| A38 obstruction | 51°45′55″N 2°19′52″W / 51.7652°N 2.3310°W | SO772074 | |

| M5 obstruction | 51°45′31″N 2°19′29″W / 51.7586°N 2.3246°W | SO776067 | |

| Ocean railway culvert | 51°44′39″N 2°17′43″W / 51.7441°N 2.2954°W | SO797050 | |

| A419 bridge, Dudbridge | 51°44′32″N 2°14′22″W / 51.7421°N 2.2394°W | SO835048 | |

| Jn with Thames and Severn Canal | 51°44′38″N 2°13′38″W / 51.7440°N 2.2273°W | SO844050 |

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |