Harecastle Tunnel facts for kids

|

|

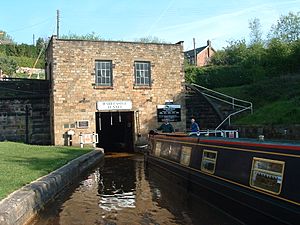

| Northern end of Telford's Harecastle Tunnel (left) next to the disused Brindley tunnel (right). | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Location | Kidsgrove to Tunstall, Staffordshire, England |

| Coordinates | 53°4′27″N 2°14′11″W / 53.07417°N 2.23639°W |

| OS grid reference | SJ843529 |

| Status | Open |

| Waterway | Trent and Mersey Canal |

| Start | 53°3′46.62″N 2°13′35.64″W / 53.0629500°N 2.2265667°W |

| End | 53°5′4.44″N 2°14′39.24″W / 53.0845667°N 2.2442333°W |

| Operation | |

| Owner | British Waterways |

| Technical | |

| Design engineer | Thomas Telford |

| Construction | 1824–1827 |

| Length | 2,675 metres (2,926 yards) |

| Towpath | No (removed) |

| Boat-passable | Yes |

The Harecastle Tunnel is a long canal tunnel. It is found on the Trent and Mersey Canal in Staffordshire, England. The tunnel connects the towns of Kidsgrove and Tunstall. It is about 1.6 miles (2.6 km) long. This made it one of the longest tunnels in the country.

The tunnel was built to help transport coal. This coal was used in the kilns of the Staffordshire Potteries. The canal goes under Harecastle Hill, which is 195 meters (640 feet) high. This hill is near Goldenhill, a high area in Stoke-on-Trent.

Even though it's called "Harecastle Tunnel," there are actually two separate tunnels. They run side-by-side and were built almost 50 years apart. The first tunnel was built by James Brindley in the late 1700s. The second, larger tunnel was designed by Thomas Telford. It opened in the late 1820s.

Today, only the Telford tunnel can be used by boats. The Brindley tunnel partly collapsed before the First World War and was closed. Since the Telford tunnel is only wide enough for one boat, boats take turns. They go through in groups, first northbound, then southbound. Big electric fans at the south end help keep fresh air flowing through the tunnel.

Contents

Brindley Tunnel: The First Passage

The first tunnel through Harecastle Hill was planned by a canal engineer named James Brindley. Building started in 1770. Workers first marked the tunnel's path over the hill. Then, they dug fifteen vertical shafts down into the ground. From the bottom of these shafts, workers dug outwards to create the canal path.

However, the ground was tricky. It changed from soft earth to hard rock called Millstone Grit. This caused many problems for the engineers. The tunnel sites also often filled with water. To fix this, Watt steam engines were brought in to power pumps. Stoves were also put at the bottom of special pipes to help with air flow.

Brindley died in 1772, but the tunnel was finished in 1777. It was about 2,880 yards (2.6 km) long. When it opened, it became the longest tunnel on Britain's canal network. It was even longer than the Norwood Tunnel, which Brindley also built.

How Boats Traveled Through Brindley's Tunnel

This tunnel had no towpath. A towpath is a path next to a canal where horses would pull boats. So, boatmen had to "leg" their way through the tunnel. Legging meant lying on the roof of the boat. Then, they would use their feet to push against the tunnel walls. This was very slow and hard work. It took about three hours to get through the tunnel.

While the narrowboats went through the tunnel, their horses were led over Harecastle Hill. They used a path called "Boathorse Road." A special lodgekeeper watched the horses. Often, children from the boats would lead the horses across the hill between Kidsgrove and Tunstall.

Why a Second Tunnel Was Needed

Soon after the Brindley tunnel opened, its problems became clear. The Industrial Revolution was happening. This meant there was a huge demand for coal and other materials in the Potteries. But the tunnel was too small. It was only 12 feet (3.7 meters) high and 9 feet (2.7 meters) wide. This limited how much traffic could pass through.

By the early 1800s, it was decided that a second tunnel was needed. This new tunnel would be built by Thomas Telford. The Brindley tunnel was used for the rest of the 1800s. But in the early 1900s, it started to sink in places. In 1914, it was closed for good after part of it collapsed.

Engineers stopped checking the old Brindley tunnel in the 1960s. Since then, no one has explored much of its inside. Both entrances are now blocked by gates. Water from the Brindley tunnel flows into the canal. This water has a lot of iron in it. This makes the canal water look rusty. There are plans to use reed beds at the northern entrance to help filter this water.

Telford Tunnel: The Modern Passage

By the early 1800s, Brindley's tunnel was causing big delays. It was a major bottleneck on the Trent and Mersey Canal. In the 1820s, a group decided that a second tunnel was necessary. They hired the famous Scottish engineer, Thomas Telford, to do the job.

Thanks to new engineering methods, the larger Telford tunnel was finished quickly. It took only three years to build, opening in 1827. This tunnel had a towpath. This meant horses could now pull boats through the 2,926-yard (2.6 km) tunnel. This made journeys much faster. For a while, both tunnels were used. Each tunnel carried boat traffic in opposite directions.

Side Tunnels and Modern Use

Inside the Telford tunnel, you can still see where smaller tunnels once connected. These tunnels led to coal mines around Goldenhill. This meant coal could be loaded directly onto boats underground. It saved the effort of bringing it to the surface. These side tunnels also helped drain water from the mines. Only small narrowboats, carrying about 10 tonnes, could use these side tunnels.

Over time, parts of the Telford tunnel also sank. This lowered the height inside and made the towpath uneven. So, in 1914, an electric tug boat was introduced. This tug could pull up to 30 boats at once through the tunnel. A second tug was added in 1931. The tugs were used until 1954.

In 1954, large fans were built at the south entrance. These fans help move air through the tunnel for boats powered by diesel engines. When boats are inside, a special airtight door closes. This helps fresh air flow constantly. The fans protect boaters from harmful diesel fumes. Today, a trip through the tunnel takes about 30 to 40 minutes.

In the late 1900s, the Telford tunnel had more sinking problems. It was closed temporarily between 1973 and 1977. During this time, the old towpath was removed. This made the tunnel wider and improved air flow even more.

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |