Wey and Godalming Navigations facts for kids

Quick facts for kids River Wey and Godalming Navigations |

|

|---|---|

Catteshall Lock, the southernmost lock on the Navigations at Farncombe, Godalming, Surrey.

|

|

| Specifications | |

| Length | 19.5 miles (31.4 km) |

| Maximum boat length | 73 ft 6 in (22.40 m) |

| Maximum boat beam | 13 ft 10.5 in (4.23 m) |

| Locks | 16 |

| Status | open |

| Navigation authority | National Trust |

| History | |

| Principal engineer | Sir Richard Weston |

| Other engineer(s) | John Smeaton |

| Construction began | 1651 |

| Date of first use | 1653 |

| Date extended | 1764 |

| Geography | |

| Start point | River Thames |

| End point | Godalming (originally Guildford) |

| Connects to | Basingstoke Canal Wey and Arun Junction Canal |

The River Wey Navigation and Godalming Navigation are two waterways in Surrey, England. Together, they create a continuous route about 20 miles (32 km) long. This route goes from the River Thames near Weybridge all the way to Godalming, passing through Guildford. People often call the whole route the Wey Navigation.

Both waterways are owned by the National Trust, a charity that looks after historic places and natural beauty spots. The River Wey Navigation connects to the Basingstoke Canal at West Byfleet. The Godalming Navigation links up with the Wey and Arun Canal near Shalford. These navigations are a mix of man-made canal sections and parts of the River Wey that have been improved. The river sections were made deeper and straighter for boats.

The River Wey was one of the first rivers in England to be made easy for boats to use. The River Wey Navigation opened in 1653. It had 12 locks between Weybridge and Guildford. The Godalming Navigation, which added four more locks, was finished in 1764. Large boats stopped using the waterways for trade in 1983. The Wey Navigation was given to the National Trust in 1964, and the Godalming Navigation in 1968.

Contents

The River Wey starts from two main branches, which meet at Tilford. The river then flows through Godalming and cuts through the chalk hills of the North Downs at Guildford. It continues through the Surrey Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty before joining the River Thames at Weybridge. Small boats had used the river since medieval times. Some improvements were made to the river channel starting in 1618.

Sir Richard Weston owned land along the river. He had already dug a 3-mile (5 km) channel through his land between 1618 and 1619. This channel went from Stoke Mills to Sutton Green. It included a path for horses to pull boats (a towing path) and several bridges. It also had special gates called sluices. These sluices allowed him to flood 150 acres (61 ha) of his land in a controlled way. This created "water-meadows" which were good for farming.

Because he was a Catholic and supported the King, his property was taken away (this is called sequestration) during the English Civil War. He had to flee to the Netherlands. There, he learned about inland waterways and how "pound locks" worked. Pound locks are like water elevators that lift or lower boats between different water levels.

Weston returned to England in the late 1640s. He suggested a plan to make the Wey navigable to Guildford using these new locks. Guildford town leaders had asked Parliament in 1621 and 1624 for a plan using "flash locks." Flash locks were simpler gates that just released a rush of water to help boats over shallow spots. But nothing came of these earlier ideas.

To move his plan forward, Weston needed his property back. He also needed someone important to support his idea. He found an ally in James Pitson, a former Major in Cromwell's army. Pitson was now a Commissioner for Surrey. He helped Weston get his property back. Pitson then presented a bill (a proposed law) to Parliament in December 1650. This bill became an Act of Parliament on 26 June 1651.

The Act allowed the people building the canal, called "undertakers," to raise £6,000. They did this by selling 24 shares. Weston bought 12 shares, and Pitson, Richard Scotcher, and another person bought four shares each. The Act also set a maximum price, or "toll," for carrying goods along the navigation. This was set at four shillings (20p). This was cheaper per mile than other waterways at the time. There was also a charge for passengers and for goods if the undertakers used their own barges.

Work started in August 1651. Weston was the engineer, and about 200 men worked on the project. Weston died on 17 May 1652. But by then, he had already finished 10 miles (16 km) of the 15-mile (24 km) route. He had also put in an extra £1,000 and timber worth £2,000 from his own land. His son, George, took over his role. Scotcher managed the money and the workers. Pitson found others to help pay for the project.

The work was finished in November 1653, costing £15,000. It included about 9 miles (14 km) of new cuts, four new weirs, twelve bridges, and a wharf (a loading area) at Guildford. The water level dropped by 72 feet (22 m) between Guildford and Weybridge. Some records say 10 new locks were built, others say 12. The new locks were made with earth sides and timber frames.

The navigation was a success, bringing in £1,500 in tolls each year. However, there were many arguments and lawsuits about money for several years. These involved Weston's older son John, Scotcher, Pitson, and other people who had contributed money. A second Act of Parliament was passed in 1671 to try and sort things out. This Act put the river under the control of six "trustees" and set up a board to settle disputes. It took another six years to resolve everything. By then, the navigation needed thousands of pounds for repairs because it had been neglected and damaged.

Another bill was presented to Parliament in 1759. This was to allow the navigation to be extended another 4.5 miles (7.2 km) up to Godalming. This bill did not pass, but another Act of Parliament was approved the next year. John Smeaton and then Richard Steadman worked as engineers. This extension involved building four more locks and cost £6,450. The Godalming Navigation opened for trade in 1763. It was managed by "Commissioners," who were a separate group from those managing the navigation below Guildford.

The waterways were used to transport heavy goods by barge to London. Things like timber, corn, flour, wood, and gunpowder from the Chilworth mills went north along the canal and then down the Thames to London. Coal was brought back, mainly for making gunpowder and for blacksmiths. Other goods brought back included sugar and bark, which was used for tanning leather.

The trade in timber for shipyards on the Thames started long before the river was made into a canal. In 1664, 4,000 loads of timber were reported to have gone down the river. Much of the timber used to rebuild London after the Great Fire was moved this way. Stone for rebuilding St Paul’s Cathedral also came from quarries at Guildford.

Daniel Defoe, a famous writer, noted that huge amounts of timber used the river. This timber came to Guildford from forests in Sussex and Hampshire, up to 30 miles (48 km) away, during the summer. The Rev. W Gilpin wrote in 1776 that timber was floated down the river. Each load was steered by a man with a pole. There was also a lot of trade in hoops (for making barrels) and paper. Defoe also said that corn was bought at Farnham market, taken to mills on the river by boat, and then shipped to London after being processed into flour.

Trade grew during the American War of Independence (1780-1783). War supplies were moved from London to Godalming and then taken by land to Portsmouth. The navigation also earned extra money from traffic using the first 3 miles (4.8 km) to reach the Basingstoke Canal, which opened in 1794. During the Napoleonic Wars, people feared the French. So, trade between London and the south and west was not sent by sea, and the navigation benefited again.

The Wey and Arun Canal connected the Godalming Navigation to the River Arun in Sussex in 1816. This was part of a big plan to link London to Portsmouth. But it opened just as the war with France ended. Coastal trade by sea started again, so the new canal never became as busy as expected. People thought the new canal would make coal cheaper at Guildford. But improvements to the Thames and lower coal prices meant Guildford still got its coal from London. Coal traffic continued south along the Wey and Arun as far as Loxwood.

Profits for the navigation increased. They averaged £2,046 from 1794 to 1798, and rose to £4,079 from 1809 to 1813. In 1780, 24,006 tons of goods were carried. By 1830, this had increased to 55,035 tons. In 1831, 827 loaded boats went upstream, carrying 31,544 tons. Of this, coal was 12,859 tons, corn 6,155 tons, and groceries 5,719 tons. Going downstream, 867 loaded boats carried 25,645 tons. Timber, in various forms, made up 9,632 tons. Most of the hoops for barrels and bark for tanning came from the Wey and Arun Canal. Processed flour from the mills along the river contributed 5,593 tons. The rest was mostly manufactured goods.

After 1677, the shares in the Wey Navigation were split into two halves, called "moieties." George Langton eventually owned all the shares in one half by 1699. He managed the navigation until 1715. Then, Winifred Hodges, who inherited shares from another owner, gained joint control. Her shares were sold to Lord Portmore in 1723. The Portmore and Langton families continued to manage the navigation into the 1800s. However, when a shareholder died, their shares were often split among many heirs. This made management more complicated.

The Stevens family became involved with the navigation in 1812. The first William Stevens started as the lock-keeper at Trigg Lock. He moved to Thames Lock in 1820. In 1823, he became the "wharfinger" at Guildford. A wharfinger is someone who manages a wharf, where boats load and unload goods. He also built a successful business selling coal. His son, William Stevens II, took over in 1856. William II became the general manager of the Godalming Navigation in 1869. He bought the Portmore family's shares in 1888. When he died two years later, his son, William Stevens III, became the manager of both navigations. He bought most of the Langton shares to ensure his family owned most of the navigation.

The arrival of railways from the 1840s caused many canals to decline. The Wey and Arun Canal lost most of its trade by the 1850s and closed in 1871. This did not affect the Wey Navigation much, as corn mills still sent their goods by boat. But it severely impacted the Godalming Navigation, which had little other business.

The amount of goods carried fell from a high of 86,003 tons in 1838 to 24,581 tons in 1890. However, the Stevens family worked hard to keep the navigation going. Traffic rose again to over 30,000 tons from 1890 to 1910, reaching 51,115 tons in 1918. In 1912, Stevens went to court to transfer the Trustees' powers to his family. The Stevens family also owned boats and carried goods themselves. Their fleet helped keep trade healthy between 1918 and 1939. The connection to the London Docks via the Thames and the many corn mills on the river also helped. Leisure boat traffic also steadily increased, bringing in £371 as early as 1893.

Decline and Restoration

Harry Stevens took over running the navigations in 1930. At this time, industries were closing or moving their transport to roads. Also, a major project to improve flood control in the Wey valley was starting. This involved building new weirs and channels, like the Broad Mead Cut.

By the 1940s, the Godalming Navigation was almost unused. Trade declined when Newark Mill closed during the Second World War. When traffic from Coxes Mill stopped in the 1960s, the navigation was no longer making enough money. Harry Stevens gave it to the National Trust in 1964. Ownership officially passed to them in 1971 after Stevens' wife died. The Commissioners of the Godalming Navigation gave their rights to Guildford Corporation in 1968, who then passed them to the National Trust. For the first time, both parts of the river were owned by the same group. The last commercial barge ran in 1969, though there was some commercial traffic in the early 1980s.

The National Trust had some experience managing waterways, having looked after the Stratford Canal since 1960. Early restoration work was done by volunteers. These volunteer groups were organized through a newsletter called Navvies Notebook. The Trust has set up a visitor centre at Dapdune Wharf. Eleven barges were built there for the navigation. Two of them are on display. Reliance was built in 1931-1932. It was found abandoned in mud flats after sinking in London in 1968. It was rescued in 1996 and restored as a display. Perseverance IV was built in 1935 and was used for trade until 1982. It was partly restored in 1998.

Towpath Collapse

On 2 November 2019, the bridge for the towpath over the Tumbling Bay Weir collapsed. A temporary barrier was placed upstream by Guildford Rowing Club. The section between the barrier and Millmead lock was drained for repairs. The river flow was sent through another gate opposite the club. Metal poles were put up around the weir to allow work to continue. The emptied section of the river was refilled to allow boats to pass again. Refilling started on 15 June 2020, and by the end of that week, boats could use the navigation again. Workers also took the chance to install new sluice gates and a planned fish ladder. As of September 2020, the towpath was still closed at that spot.

Features Along the Canal

Here are some interesting places you can see along the navigation, starting from the River Thames and going upstream.

Between Town Lock (or Weybridge Lock) and Coxes Lock is the Blackboys footbridge. After a railway bridge, you'll see Coxes Mill, which has three old, listed buildings. Coxes Lock is the deepest lock without a lock-keeper on the navigation. It lifts boats 8 feet 6 inches (2.59 m). It has a small island and a weir that helps drain the mill pond.

Between New Haw Lock and Pyrford Lock, you'll find one end of the Basingstoke Canal. Just before the Woodham footbridge, there's the Byfleet boat club, built in the 1900s. You'll also see Grist Mill, Parvis Wharf, Murray's footbridge, and Dodds footbridge.

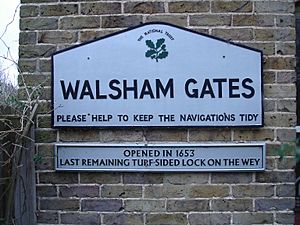

Between Pyrford Lock and Newark Lock are the Walsham Gates and the old, broken walls of Newark Priory on its own grassy island. Between Papercourt Lock and Triggs Lock, you'll find Tanyard footbridge, High Bridge (for walkers), Cartbridge Wharf, Cart Bridge, and Worsford Gates. The special gear on the Worsford gates, used to open and close them, is very old and probably unique now.

Between Triggs Lock and Bowers Lock are the Send Church footbridge and Broad Oak Bridge. Between Stoke Lock and Millmead Lock, you'll see Stoke Mill, Dapdune Wharf, and Guildford Town Wharf with its old crane. Finally, between Millmead Lock and Unstead Lock are the Guildford boathouse, a footbridge for the North Downs Way walking path, and Broadford Bridge.

| Number | Name | Change in level |

|---|---|---|

| – | Stop lock | – |

| 1 | Thames lock | 8 ft 6 in (2.59 m) |

| 2 | (Weybridge) Town lock | 5 ft 6 in (1.68 m) |

| 3 | Coxes lock | 8 ft 6 in (2.59 m) |

| 4 | New Haw lock | 6 ft 8 in (2.03 m) |

| 5 | Pyrford lock | 4 ft 9 in (1.45 m) |

| 6 | Walsham flood gates | – |

| 7 | Newark lock | 5 ft 3 in (1.60 m) |

| 8 | Papercourt lock | 8 ft 0 in (2.44 m) |

| 9 | Worsfold flood gates | – |

| 10 | Triggs lock | 6 ft 6 in (1.98 m) |

| 11 | Bower’s lock | 7 ft 0 in (2.13 m) |

| 12 | Stoke lock | 6 ft 9 in (2.06 m) |

| 13 | Millmead lock | 6 ft 3 in (1.91 m) |

| 14 | St Catherine’s lock | 2 ft 9 in (0.84 m) |

| 15 | Unstead lock | 6 ft 6 in (1.98 m) |

| 16 | Catteshall lock | 5 ft 6 in (1.68 m) |

The total drop in water level through all the locks from Godalming to the Thames is 88 feet 6 inches (27.0 m).

The "pound gate" below Thames Lock is used when the Thames water level is low. It might have been added because the Thames still had some tides at this point when the navigation was built. Thames Lock was rebuilt with concrete walls in 1863. This was an early use of concrete and greatly reduced maintenance costs compared to older wooden or earth-sided locks. Eventually, all the locks on the navigation were rebuilt this way.

The largest boat allowed on the navigation can be 73 feet 6 inches (22.4 m) long and 13 feet 10.5 inches (4.23 m) wide. The maximum depth a boat can sit in the water (draught) is 4 feet (1.2 m) up to Coxes Lock. Then it's 3 feet 3 inches (0.99 m) to Guildford, and 2 feet 6 inches (0.76 m) to Godalming. The height clearance under bridges decreases from 7 feet (2.1 m) to 6 feet (1.8 m) above Guildford.

Towpath and Footpath Links

The towpath is a public path that runs alongside the canal. It's a free, car-free route that goes from north to south. It connects with the Basingstoke Canal towpath at Byfleet. It also links to many other public footpaths and two National Trails. These are the Thames Path at Weybridge and the North Downs Way at St. Catherines, Guildford. This part of the towpath is even part of the European long-distance path E2. This long path stretches from Galway in Ireland to Nice on the Mediterranean coast of France.

Downs Link

The old railway line between Guildford and Horsham, called the Cranleigh Line, crossed the Wey just south of the entrance to the Wey and Arun Canal. This railway line carried building materials, farm goods, wood, and coal. It competed directly with the canal and helped lead to its closure. However, the railway closed in 1965 because of the Beeching Axe, which shut down many railway lines. The bridge over the river and canal was taken down soon after, leaving only its supports.

To celebrate the 21st anniversary of the Downs Link national trail opening, a new footbridge was built in the same spot. It uses the old railway bridge supports to connect the trails that run along the former railway track. The Unstead Woods Downslink Bridge opened on 7 July 2006. It's a single metal bridge that allows cyclists and walkers to cross the river.

Gallery

-

Part of the house where John Donne lived, Pyrford

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |