John Donne facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Very Reverend

John Donne

|

|

|---|---|

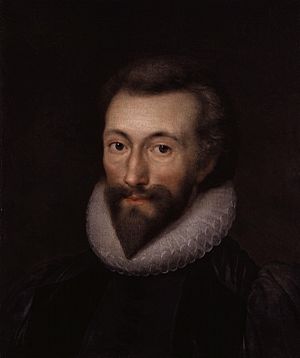

Donne, painted by Isaac Oliver

|

|

| Born | 22 January 1572 London, England |

| Died | 31 March 1631 (aged 59) London, England |

| Occupation |

|

| Nationality | English |

| Alma mater | Hart Hall, Oxford University of Cambridge |

| Genre | Satire, love poetry, elegy, sermons |

| Subject | Love, religion, death |

| Literary movement | Metaphysical poetry |

| Spouse |

Anne More

(m. 1601; |

| Children | 12 (incl. John and George) |

| Relatives | Edward Alleyn (son-in-law) |

John Donne (/dʌn/ dun; 1571 or 1572 – 31 March 1631) was a famous English poet, scholar, and priest. He was born into a family that secretly practiced Catholicism when it was against the law in England. Later in life, he became a priest in the Church of England.

With support from the King, he became the Dean of St Paul's Cathedral in London from 1621 to 1631. He is known as the most important of the "metaphysical poets." His poems are special because they use clever comparisons (called metaphors) and talk about feelings in a very real way. He wrote many types of poems, including love poems, religious poems, and funny poems (satires). He was also famous for his powerful speeches, called sermons.

Donne's writing style was unique. He often started poems suddenly and used surprising ideas. He also wrote in a way that sounded like everyday talk. This was different from the smooth, traditional poems of his time. He was very good at using "metaphysical conceits," which are extended metaphors that link two very different things in a surprising way.

Even though John Donne was very smart and talented, he was poor for many years. He often had to rely on his rich friends for help. In 1601, he secretly married Anne More, and they had twelve children together. In 1615, he became a priest, even though he wasn't sure he wanted to at first. The King actually asked him to do it. He also served as a member of Parliament twice.

Contents

John Donne's Life Story

Growing Up

John Donne was born in London in 1571 or 1572. His family was Roman Catholic, and at that time, practicing Catholicism was against the law in England. John was the third of six children. His father, also named John Donne, was a warden in the Ironmongers Company, a group of metalworkers in London. His father tried to avoid trouble with the government because of their religion.

When John was four, his father died in 1576. His mother, Elizabeth, had to raise the children alone. Elizabeth also came from a Catholic family. Her father was a playwright, and her uncle was a Jesuit priest. She was also related to Thomas More, a famous English lawyer and writer. A few months after her husband died, John's mother married Dr. John Syminges, a rich widower who had three children of his own.

Donne was taught privately at home. In 1583, when he was 11, he started studying at Hart Hall (now Hertford College, Oxford). After three years, he went to the University of Cambridge for another three years. However, he couldn't get a degree from either university because he was Catholic. He refused to take the "Oath of Supremacy," which said the King was the head of the church. This oath was required to graduate. In 1591, he began studying law in London.

In 1593, Queen Elizabeth I made a law against Catholics who didn't attend the Church of England. John's brother, Henry, was arrested that same year for hiding a Catholic priest. Henry died in prison from the bubonic plague. This event made John start to question his Catholic faith.

During and after his studies, Donne spent a lot of his money on books, travel, and fun activities. He traveled across Europe. He also joined the Earl of Essex and Sir Walter Raleigh in battles against the Spanish in 1596 and 1597. He saw the Spanish flagship, the San Felipe, sink.

By age 25, he was ready for a career in diplomacy, which means working with other countries. He became the main secretary to Sir Thomas Egerton, a very important government official. Donne lived in Egerton's London home, York House, Strand, which was close to the Palace of Whitehall, a major social center in England.

His Marriage to Anne More

Over the next four years, Donne fell in love with Anne More, who was Egerton's niece. They secretly got married just before Christmas in 1601. This was against the wishes of both Egerton and Anne's father, George More. When their marriage was discovered, it ruined Donne's career. He was fired and put in Fleet Prison. The priest who married them and Donne's brother, Christopher, were also imprisoned. Donne was released soon after when it was proven that his marriage was legal. He then helped get the others released. When Donne wrote to his wife about losing his job, he famously wrote after his name: John Donne, Anne Donne, Un-done. It wasn't until 1609 that Donne made up with his father-in-law and received Anne's dowry (money or property given by the bride's family).

After being released from prison, Donne had to live a quiet life in the countryside. He lived in a small house in Pyrford, Surrey, owned by Anne's cousin. They lived there until late 1604. In 1605, they moved to another small house in Mitcham, Surrey. Donne struggled to make a living as a lawyer. Anne gave birth to a new baby almost every year. He also helped a bishop named Thomas Morton write pamphlets against Catholics. Even so, Donne was always worried about money.

Anne gave birth to twelve children in sixteen years of marriage. Ten of their children survived: Constance, John, George, Francis, Lucy, Bridget, Mary, Nicholas, Margaret, and Elizabeth. Sadly, three of them (Francis, Nicholas, and Mary) died before they were ten years old.

Anne died on 15 August 1617. Donne was very sad about her death. He wrote about his love and loss in his 17th Holy Sonnet.

His Career and Later Life

In 1602, Donne was chosen to be a member of Parliament (MP) for the Brackley area. This job did not pay money. Queen Elizabeth I died in 1603, and King James VI of Scotland became King James I of England. During this time, writing poems for wealthy friends was a way to get support. Many of Donne's poems were written for rich friends or people who supported him. One important supporter was Sir Robert Drury, an MP, whom he met in 1610. Drury became his main supporter and gave Donne and his family an apartment in his large house in Drury Lane.

In 1610 and 1611, Donne wrote two books against the Catholic Church for Morton. He then wrote two long poems, An Anatomy of the World (1611) and Of the Progress of the Soul (1612), for Drury.

Donne was an MP again in 1614 for Taunton. Even though King James liked Donne's work, he would not give him a job at court. Instead, the King told him to become a priest. Finally, Donne agreed to the King's wishes, and in 1615, he became a priest in the Church of England.

In 1615, Cambridge University gave Donne an honorary degree in divinity. He also became a chaplain to the King that same year. From 1616 to 1622, he taught divinity at Lincoln's Inn. In 1618, he became a chaplain to Viscount Doncaster, who was an ambassador to German princes. Donne did not return to England until 1620. In 1621, Donne was made Dean of St Paul's, a very important and well-paid job in the Church of England. He held this position until he died in 1631.

He also became the rector (head priest) of several churches, including one in Blunham, Bedfordshire. Blunham Parish Church has a beautiful stained glass window in his memory. During his time as dean, his daughter Lucy died at age eighteen. In late 1623, he became very sick, possibly with typhus.

While he was getting better, he wrote a series of thoughts and prayers about health, pain, and sickness. These were published as a book in 1624 called Devotions upon Emergent Occasions. One part of this book, Meditation XVII, has the famous lines: "No man is an Iland" (meaning no one is truly alone) and "...for whom the bell tolls" (referring to a bell ringing for a funeral). In 1624, he became the vicar of St Dunstan-in-the-West. He became known as a very good preacher. About 160 of his sermons still exist, including Death's Duel, his famous sermon given to King Charles I in February 1631.

His Death

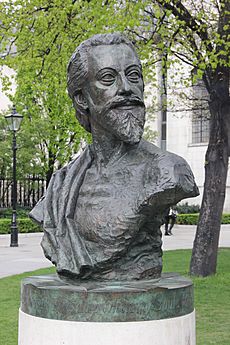

John Donne died on 31 March 1631. He was buried in the old St Paul's Cathedral. A statue of him was put there, with a Latin message that he probably wrote himself. This statue was one of the few things that survived the Great Fire of London in 1666. It is now in the new St Paul's Cathedral. People say Donne posed for the statue himself to show how he would look at the resurrection. In 2012, a bust (head and shoulders statue) of the poet was placed outside the cathedral churchyard.

What John Donne Wrote

Donne's earliest poems showed that he knew a lot about English society and wasn't afraid to criticize its problems. His satires (funny but critical writings) talked about common issues in the Elizabethan era, like unfair legal systems, bad poets, and proud courtiers. His descriptions of sickness and plague showed his strong, critical view of a society full of foolish and dishonest people. However, his third satire focused on the idea of true religion, which was very important to Donne. He believed it was better to carefully think about one's religious beliefs than to just follow traditions without question.

Some people think that Donne's many illnesses, money problems, and the deaths of his friends made his later poems more serious and religious. This change can be seen in "An Anatomy of the World" (1611). Donne wrote this poem to remember Elizabeth Drury, the daughter of his supporter, Sir Robert Drury. This poem talks about Elizabeth's death with great sadness, using it as a symbol for the fall of man and the destruction of the universe.

The increasing seriousness in Donne's writing can also be seen in his religious works that he started writing around the same time. After becoming a member of the Anglican Church, Donne quickly became known for his sermons and religious poems. Towards the end of his life, Donne wrote works that challenged death and the fear it caused. He believed that those who die go to Heaven to live forever. An example of this challenge is his Holy Sonnet X, "Death Be Not Proud".

Even when he was dying in 1631, he got out of bed to give his "Death's Duel" sermon. This sermon was later called his own funeral sermon. "Death's Duel" describes life as a journey towards suffering and death. It says that death is just another part of life. Hope is found in salvation and living forever by embracing God, Christ, and the Resurrection.

His Writing Style

Donne's work has been discussed a lot over the years, especially his "metaphysical" style. He is seen as the most important of the metaphysical poets. This term was first used in 1781 by Samuel Johnson, after a comment by John Dryden. Dryden wrote in 1693 that Donne "affects the metaphysics," meaning he liked to use complex philosophical ideas in his poems, even in love poems where simple feelings should be.

In the early 17th century, a group of writers appeared who were called "metaphysical poets." At first, some poets didn't like Donne's style, thinking his clever comparisons were too much. However, later poets like Coleridge and Browning brought his work back into popularity. In the early 20th century, poets like T. S. Eliot also admired him.

Donne is a master of the metaphysical conceit. This is a long, clever comparison that links two very different ideas into one, often using vivid pictures. For example, in "The Canonization", he compares lovers to saints. Unlike other common comparisons in poems of his time (like comparing a rose to love), metaphysical conceits go much deeper by comparing two completely unlike things. One of Donne's most famous comparisons is in "A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning". Here, he compares two separated lovers to the legs of a compass.

Donne's works are also very witty. He uses surprising ideas, wordplay (puns), and clever comparisons. His writings are often ironic and can be a bit cynical, especially about love and why people do things. Common topics in Donne's poems are love (especially when he was young), death (especially after his wife died), and religion.

John Donne's poetry marked a change from traditional forms to more personal writing. He is known for his poetic metre, which had changing and uneven rhythms that sounded like everyday speech. Because of this, the more traditional poet Ben Jonson once joked that Donne "deserved hanging" for not keeping a regular rhythm.

Some experts believe that Donne's writings show the changes in his life. They think his love poems and satires were from his youth, and his religious sermons were from his later years. However, other experts, like Helen Gardner, question if this is true. Most of his poems were published after he died in 1633. The exceptions are his Anniversaries, published in 1612, and Devotions upon Emergent Occasions, published in 1624. His sermons are also dated, sometimes with specific dates.

What He Left Behind

John Donne is remembered in the Calendar of Saints of the Church of England and other churches. He is honored on 31 March for his life as both a poet and a priest.

Several pictures were made of Donne during his lifetime. The earliest is a portrait from 1594, now in the National Portrait Gallery, London. It shows the poet looking thoughtful. This portrait was mentioned in Donne's will. Other paintings include one from 1616 and another from 1622. In 1911, the artist Stanley Spencer painted a vision called John Donne arriving in heaven.

How people understood Donne was shaped by how his writings were published after his death. Since Donne didn't publish most of his works himself, others did it in the years after he died. These publications often showed a story of Donne changing from a wild young man ("Jack Donne") to a respected priest ("Dr. Donne"). For example, early editions of his poems mixed love poems and religious poems. But after 1635, they separated them into "Songs and Sonnets" and "Divine Poems." This made people think of his life as a transformation.

A similar effort to explain Donne's early writings happened with his prose (non-poetry) works. In 1652, a book combined texts from throughout his life, including funny works and more religious ones. In the introduction, Donne's son said his father's different writings were like Jesus' miracles, showing a journey from fun writings to more spiritual ones.

Donne's first biographer, Izaak Walton, also helped create this idea of Donne as a wild young man who became a preacher. Walton compared Donne's life to the transformation of St. Paul. He wrote that where Donne "had been a Saul… in his irregular youth," he became "a Paul, and preach[ed] salvation to his brethren."

The idea that Donne's writings show two different stages of his life is still common. However, many experts have challenged this view. In 1948, Evelyn Simpson wrote that a close look at his works shows he wasn't like a "Jekyll-Hyde" character. She believed there was a main unity in his personality, despite his many different traits.

In Other Books

After Donne died, many poets wrote tributes to him. One of the most important was his friend Lord Herbert of Cherbury's "Elegy for Doctor Donne." Later editions of Donne's poems also included "Elegies upon the Author" written by other churchmen and court writers. In 1963, Joseph Brodsky wrote "The Great Elegy for John Donne."

Starting in the 20th century, several historical novels (stories based on real history) were written about parts of Donne's life. His secret marriage to Anne More is the subject of Take Heed of Loving Me: A novel about John Donne (1963) by Elizabeth Gray Vining and The Lady and the Poet (2010) by Maeve Haran. Both John and Anne also appear in Mary Novik's Conceit (2007), which focuses on their rebellious daughter Pegge. Other books include Death's Duel: a novel of John Donne (2015) by Garry O'Connor, which is about Donne as a young man.

He also plays a big part in Christie Dickason's The Noble Assassin (2012). This novel is about Donne's supporter, Lucy Russell, Countess of Bedford. Finally, there is Bryan Crockett's Love's Alchemy: a John Donne Mystery (2015). In this story, the poet is forced to work as a spy and tries to prevent political problems while outsmarting a character named Cecil.

Music Inspired by Donne

Even during his lifetime and in the century after his death, some of Donne's poems were set to music. These included songs by Alfonso Ferrabosco the younger, John Cooper, Henry Lawes, and John Dowland.

After the 17th century, there weren't many musical settings until the early 20th century. Some of the first were by Havergal Brian (1905), Eleanor Everest Freer (1905), and Walford Davies (1909). In 1916–18, Hubert Parry set Donne's "Holy Sonnet 7" ("At the round earth's imagined corners") to music in his choral work, Songs of Farewell. In 1945, Benjamin Britten set nine of Donne's Holy Sonnets in his song cycle The Holy Sonnets of John Donne. In 1968, Williametta Spencer used Donne's text for her choral work "At the Round Earth's Imagined Corners." John Adams also used Donne's text in his choral piece Harmonium (1981) and his opera Doctor Atomic.

Donne's work has also appeared in popular music. John Renbourn's 1966 album John Renbourn includes a version of "Go and Catch a Falling Star." In 1992, the band In the Nursery used a reading of Donne's "A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning" for one of their songs.

Donne's prose writings have also been set to music. In 1954, Priaulx Rainier used some in her Cycle for Declamation for solo voice. In 2009, the American composer Jennifer Higdon created the choral piece On the Death of the Righteous, based on Donne's sermons. More recently, the Russian composer Anton Batagov released "I Fear No More, selected songs and meditations of John Donne" (2015).

The singer-songwriter Van Morrison mentions the poet in his song "Rave On, John Donne" from his 1983 album Inarticulate Speech of the Heart.

His Main Works

- The Flea (poem) (1590s)

- Biathanatos (1608)

- Pseudo-Martyr (1610)

- Ignatius His Conclave (1611)

- A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning (1611)

- The Courtier's Library (1611, published 1651)

- The First Anniversary: An Anatomy of the World (1611)

- The Second Anniversary: Of the Progress of the Soul (1612)

- Devotions upon Emergent Occasions (1624)

- The Good-Morrow (1633)

- The Canonization (1633)

- Holy Sonnets (1633)

- As Due By Many Titles (1633)

- Death Be Not Proud (1633)

- The Sun Rising (1633)

- The Dream (1633)

- Elegy XIX: To His Mistress Going to Bed (1633)

- Batter my heart, three-person'd God (1633)

- Poems (1633)

- Juvenilia: or Certain Paradoxes and Problems (1633)

- LXXX Sermons (1640)

- Fifty Sermons (1649)

- Essays in Divinity (1651)

- Letters to severall persons of honour (1651)

- XXVI Sermons (1661)

- A Hymn to God the Father (unknown)

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: John Donne para niños

In Spanish: John Donne para niños

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |