Beeching cuts facts for kids

The Beeching Axe was a plan in the 1960s to close many railway lines in Britain. The government wanted to save money because the railway system was losing a lot of money. They decided to close lines that were not used very much or were not making a profit.

Contents

Why the Railways Changed

In the 1950s, a plan to make the railways more modern didn't work well. A lot of money was spent on new locomotives (train engines). But the railway system still had old ways of working and too many staff. This caused the railways to lose a lot of money.

In the early 1960s, the government, led by Harold Macmillan, thought that roads were the future for transport. They believed railways were old-fashioned. Some people thought this idea was linked to the transport minister, Ernest Marples, who used to work for a big road-building company.

In 1961, the government asked Dr Richard Beeching to be in charge of British Rail. His main job was to stop the railways from losing so much money.

Dr Beeching believed the railway system should be run like a business. He thought that if parts of the railway that didn't make money were closed, the rest of the system could become profitable.

He studied how much traffic each railway line carried. He found that 80% of all train journeys happened on only 20% of the railway lines. The other lines carried very little traffic and were losing money.

On March 27, 1963, Dr Beeching released his report called "The Reshaping of British Railways". It suggested a huge plan to close many lines. The newspapers called it the "Beeching Bombshell" or "Beeching Axe". Many communities were very upset because they would lose their train services.

The report suggested closing 6,000 miles of Britain's 18,000 miles of railway. Most of these were smaller, rural lines. It also said that many other lines should only carry freight (goods) and not passengers. Many smaller train stations would also close. The government agreed to this plan.

Dr Beeching's plan also included ideas to make some main lines electric and use modern containers for freight. But politicians were more interested in saving money by closing lines. However, some improvements, like making the West Coast Main Line electric, did happen.

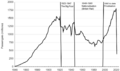

At its busiest in 1950, the British railway system had about 21,000 miles of track.

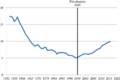

It's important to know that Beeching didn't start railway closures. Some lines had already closed in the 1950s. Between 1950 and 1963, about 3,000 miles of track were closed. But after Beeching's report, the closures happened much faster and on a larger scale.

How Many Miles Closed Each Year

Here's how many miles of railway track were closed each year:

- 1950....150 miles closed

- 1951....275 miles closed

- 1952....300 miles closed

- 1953....275 miles closed

- 1954 to 1957....500 miles closed

- 1958....150 miles closed

- 1959....350 miles closed

- 1960....175 miles closed

- 1961....150 miles closed

- 1962....780 miles closed

- 1963....324 miles closed

- 1964....1,058 miles closed

- 1965....600 miles closed

- 1966....750 miles closed

- 1967....300 miles closed

- 1968....400 miles closed

- 1969....250 miles closed

- 1970....275 miles closed

- 1971....23 miles closed

- 1972....50 miles closed

- 1973....35 miles closed

- 1974....0 miles closed

Not all the lines Beeching suggested were closed. Some stayed open for different reasons, including political ones. For example, lines in the Scottish Highlands were not making money, but they stayed open because of strong local pressure. Some lines also stayed open if they were in areas where elections were very close.

Some lines were also kept open because the local roads couldn't handle all the extra traffic if the railway closed.

So, even after Beeching, some rural railway lines still exist in Britain, but far fewer than before.

In total, 2,128 stations were closed on lines that stayed open. A few major intercity lines were also closed, like the Great Central Railway which connected London to the north of England.

In 1964, Dr Beeching released a second report, often called "Beeching II". This report suggested closing almost all railway lines except for major routes between big cities and important commuter lines around them. If this plan had happened, Britain would have had only 7,000 miles of railway, leaving large parts of the country without any trains.

The government rejected this second report. Dr Beeching left his job in 1965.

Even though politicians were ultimately responsible for the closures, Dr Beeching's name is still linked to them.

Changes in Thinking About Railways

In 1964, a new Labour government was elected, led by Prime Minister Harold Wilson. They had promised to stop the railway closures. But once they were in power, the closures continued until the end of the decade.

However, in 1965, Barbara Castle became the transport minister. She started to look at all of Britain's transport problems together. Mrs Castle decided that Britain would need at least 11,000 miles of railway for the future. She wanted to keep the railway system at about this size.

By the late 1960s, it was becoming clear that closing lines was not saving as much money as promised. The railway system was still losing money.

Barbara Castle said that some train services, even if they didn't make a profit, should get money from the government if they were important for people and communities. However, by the time this rule was put into law in 1968, many such lines had already closed. Still, this rule did help save some branch lines.

What Happened After the Closures

The main goal of the closures was to make the railways profitable, but this didn't happen. The promised savings didn't appear. This was mainly because the smaller branch lines fed passengers and goods onto the main lines. When the branch lines closed, the main lines lost this traffic, which made their financial problems worse.

The closures stopped in the early 1970s. It became clear that they weren't helping much. The small amount of money saved by closing railways was less important than the pollution and traffic jams caused by more people using cars.

The last major railway line to close was the 80-mile-long Waverly Route between Carlisle and Edinburgh in 1969. There are now plans to reopen parts of this line. Today, like most railway systems around the world, Britain's railways still need money from the government to run.

In the early 1980s, under Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, there was talk of more Beeching-style cuts. In 1983, a civil servant named David Serpell, who had worked with Dr Beeching, wrote a report suggesting more closures. But many people strongly disagreed, and the report was quickly dropped.

Most people now agree that the Beeching plan went too far. While some closures made sense, many of Beeching's cuts seem like bad decisions now. Many people regret them.

People who support the Beeching cuts say they were needed to save the railway network from financial disaster. They believe that if the cuts hadn't happened, even bigger closures would have been needed later.

One main criticism of the Beeching report was that it didn't think about future changes. For example, it didn't consider that populations in many towns would grow. So, towns that lost their railways in the 1960s now need them more than ever. Sadly, many old railway lines have been built over, making it hard to reopen them.

In recent years, a few railway closures have been reversed. Many closed stations have reopened, and passenger services have returned to lines where they were stopped. Several lines have also reopened as heritage railways, which are often run by volunteers. You can find more about them at List of British heritage and private railways.

In 1955, the British railway system had 20,000 miles of track and 6,000 stations. By 1975, it had shrunk to 12,000 miles of track and 2,000 stations. It is still roughly this size today (2003).

Images for kids

-

What's left of Rugby Central Station from the old Great Central Railway.

See also

In Spanish: Plan Beeching para niños

In Spanish: Plan Beeching para niños

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |