Chesterfield Canal facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Chesterfield Canal |

|

|---|---|

Drakeholes Tunnel in 2007

|

|

| Specifications | |

| Length | 45.5 miles (73.2 km) |

| Maximum boat length | 72 ft 0 in (21.95 m) |

| Maximum boat beam | 7 ft 0 in (2.13 m) (Locks are 14 feet (4.3 m) wide from Stockwith to Retford) |

| Status | part open, part under restoration |

| Navigation authority | Canal & River Trust, Derbyshire County Council |

| History | |

| Principal engineer | James Brindley |

| Other engineer(s) | John Varley; Hugh Henshall |

| Date of act | 1771 |

| Date completed | 1777 |

| Date closed | 1908, 1968 |

| Geography | |

| Start point | Chesterfield |

| End point | West Stockwith |

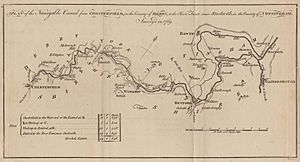

The Chesterfield Canal is a narrow canal in the East Midlands of England. People sometimes call it 'Cuckoo Dyke'. It was one of the last canals designed by James Brindley, a famous engineer. He passed away while it was still being built.

The canal opened in 1777. It stretched for about 46 miles (74 km) from the River Trent at West Stockwith, Nottinghamshire, all the way to Chesterfield, Derbyshire. It even went through the Norwood Tunnel, which was one of the longest tunnels on British canals at the time. The canal was built to move important goods like coal, limestone, and lead from Derbyshire. It also carried iron from Chesterfield and brought in things like corn and timber. Even the stone for the Palace of Westminster was moved using this canal!

The canal was quite successful and started making money by 1789. When railways became popular, some of the canal owners started a railway company. The canal became part of the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway company. Even though there were ideas to turn parts of it into a railway, it kept working well as a canal. In 1907, a part of the Norwood Tunnel collapsed because of nearby coal mining. This split the canal into two main sections. After that, the Chesterfield end was mostly used to supply water to iron factories. The section from Worksop to West Stockwith continued to carry goods until the late 1950s.

The canal was officially closed in 1961. However, many people wanted to save it. The section from Worksop to Stockwith was kept open for fun activities like boating. Other parts were sold off, and houses were even built over some of the old canal route. In 1978, the Chesterfield Canal Society was formed to help bring the canal back to life. They later became the Chesterfield Canal Trust in 1997. By 2017, over 5 miles (8 km) of the canal, including five old locks and a new one, were open for boats near Staveley. The eastern part, from Worksop to the Norwood Tunnel, was restored between 1995 and 2003. This work was paid for by grants and funds like the Heritage Lottery Fund.

Less than 9 miles (14 km) of the canal still need to be restored to connect the two open sections. This will involve building new parts of the canal. These new sections will go around the houses built at Killamarsh and replace most of the Norwood Tunnel, which cannot be fixed. The Canal & River Trust manages the eastern part of the canal. Derbyshire County Council manages the western part. This western section includes the Tapton Lock Visitor Centre and the Hollingwood Hub, which has offices for the Trust and a cafe.

Contents

History of the Canal

For a long time, moving lead mined in Derbyshire was very difficult. Workers used pack horses to carry heavy lead to Bawtry. From there, small boats took it to the River Trent, where it was moved to bigger ships. Roads were not well kept, so carts could not be used. The River Idle, which was part of the route, was also unreliable due to floods or dry spells. Despite these problems, the lead industry kept growing.

Important people, including lead and coal mine owners, started looking for better transport ideas. The towns of Chesterfield, Worksop, and Retford strongly supported building a canal. In 1769, a group published a leaflet explaining the benefits of a new canal. They hoped to get support from powerful landowners and politicians.

Planning the Route

Engineers James Brindley and John Varley surveyed the canal's path. They estimated it would cost about £94,908. Brindley shared his plans in August 1769. Another engineer, John Grundy, suggested a shorter, cheaper route. However, his route would have missed Worksop and Retford. The investors had already decided on Brindley's route because it served more towns.

On March 28, 1771, Parliament approved the plan. This allowed the canal to be built from Chesterfield, through Worksop and Retford, to the River Trent. A group of 174 people, including important figures like the Duke of Devonshire, formed a company. They raised £100,000 to pay for the construction.

Building the Canal

Construction started right away under Brindley's guidance. When he died in 1772, John Varley became the main engineer. Hugh Henshall, Brindley's brother-in-law, also helped as a consultant. By 1773, parts of the canal were almost finished. The company even started building boats to help with construction and deliver coal.

The canal opened in sections. By April 1774, it was open to Worksop, and to Retford by August. This made coal much cheaper for people in Retford. The Norwood Tunnel opened in May 1775. The canal was originally planned to be narrow. However, some shareholders paid extra to make the section from Retford to Stockwith wide enough for bigger boats. The entire canal officially opened on June 4, 1777.

How the Canal Worked

The canal was nearly 46 miles (74 km) long. It had 65 locks, which are like water elevators for boats. There were also two tunnels: a short one near Gringley Beacon and the very long Norwood Tunnel. At the time, the Norwood Tunnel was the second longest canal tunnel in Britain. The canal followed the natural shape of the land to avoid expensive digging and building. This made the route a bit winding in some places.

The canal company also built a short branch canal to a coal mine. This helped transport coal. Water for the canal came from several reservoirs. There were also other small private branches built over the years to serve quarries or other industries.

By 1789, the canal company had spent over £152,400. They started making a profit and paid their first dividend (a share of the profits) to investors. That year, over 74,000 tons of goods were carried, mostly coal. The canal continued to be profitable for many years. There were ideas to connect the Chesterfield Canal to other canals, but these plans never happened.

The Railway Era

In the 1840s, railways became very popular. Instead of being replaced by railways, some canal owners decided to join in. They formed a railway company to build new lines and even thought about turning parts of the canal into a railway. Eventually, the canal company joined with the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway. The agreement stated that the entire canal must be kept open and well-maintained.

After joining the railway company, the canal was repaired and improved in 1848. This immediately led to more traffic. Over 200,000 tons of goods were carried that year, the highest ever! The railway company even started using boats on the canal. Water levels were kept up by making the reservoirs bigger.

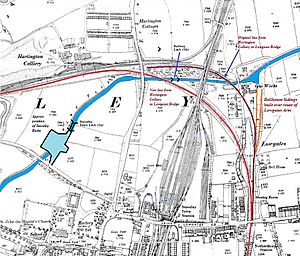

Even though railways were strong competitors, the canal continued to be used. The railway company considered turning parts of the canal into a railway several times, but these plans were always put aside. In 1889, a new railway line was built that changed parts of the canal's route. This made the canal slightly shorter. The railway stopped carrying goods on the canal soon after.

Parts of the canal near Worksop were damaged by land sinking due to coal mining. By 1905, traffic had dropped a lot. The canal was losing money. A big problem was the Norwood Tunnel, where a lot of money had been spent trying to fix damage. On October 18, 1907, a large part of the tunnel collapsed, and it was closed. This meant the canal above Worksop could no longer be used for through traffic.

The canal later became the responsibility of the London and North Eastern Railway (LNER). They kept up regular maintenance. During World War II, the canal was used to carry important supplies. The last regular commercial boats carried bricks until 1955. Some parts of the canal that were cut off by the tunnel collapse were filled in and built over.

Bringing the Canal Back to Life

After World War II, the government took over railways and canals. They wanted to close canals that weren't used for carrying goods. By 1961, the Chesterfield Canal was officially closed. People were not allowed to use it for fun. Much of it became filled with trash and dirty water.

However, a businessman named Cliff Clarke started a campaign to save the canal. The authorities agreed to keep it open for two more years. Even though some lock gates were removed, people started unofficial clean-up parties. This became more organized when the canal was managed by the British Waterways Board. The government's view changed, and in 1968, the section from the Trent to Worksop was kept open for leisure use. The rest of the canal was left as "remainder."

Restoration Efforts Begin

In 1976, the Chesterfield Canal Society was formed. They wanted to restore the canal beyond Worksop. In 1977, they held a big boat rally in Worksop to celebrate the canal's 200th birthday. Many boats and thousands of people attended. This event helped launch the Society and gain support for the canal's restoration.

In 1995, a large project began to restore the canal between Worksop and the River Ryton aqueduct. More funding came from the Heritage Lottery Fund. This big project cost £19 million. By November 2002, boats were able to use the Turnerwood lock flight again for the first time in over 70 years. Thirty locks were restored, and three bridges were rebuilt to allow boats to pass underneath. A new lock was also needed because the ground had sunk in some places. The old colliery loading basin at Shireoaks was turned into a marina for boats.

Restoring the Western Part

At first, restoration focused on the eastern part of the canal, which was easier to fix. But then, attention turned to the western part, west of the Norwood Tunnel. This section had more damage, with parts filled in or built over. Houses were even built over the canal in Killamarsh in the 1970s. However, some parts of the canal had survived well because they were used to supply water to iron factories.

Volunteers started regular work parties in 1988. The first lock, Tapton Lock, reopened in 1990. Derbyshire County Council helped by getting grants to dredge the canal and fix the towpath. By 2002, four more locks were restored, and a 5-mile (8 km) section from Chesterfield was open for boats.

In 1992, a private owner restored a section of the canal near Killamarsh. This part is now used as fishing ponds. In 1997, the Chesterfield Canal Trust was officially formed as a charity.

In 2007, a culvert (a tunnel for water) collapsed, causing a breach in the canal. This temporarily closed part of the canal. Later, a section of the canal near the old Renishaw Iron Foundry was dug out again. This work included a new footbridge.

In 2010–11, the Canal Trust got its first permanent home at Hollingwood Lock. The old lock house was renovated and expanded to become the Hollingwood Hub. It has offices, a meeting room, and a coffee shop.

A big step forward happened in early 2012 when a new mooring basin was opened at Staveley. This allowed boats to go further along the canal. The work won an award for its excellent engineering. New road construction also helped by raising bridges, making it easier for boats to pass.

North from Staveley

Moving past Staveley Basin was tricky because of an old railway bridge. This area had sunk over time. To fix this, engineers built a "dropped pound" section. This means the canal level is lowered by a new lock, Staveley Town Lock, just north of the basin. Another lock, Railway Lock, was built beyond the railway bridge. This allows boats to pass under the low bridge. Staveley Town Lock opened in May 2016.

Chesterfield Waterside Project

The southern end of the canal in Chesterfield is part of a huge £300 million project called Chesterfield Waterside. This project will create new homes and facilities in an area that was once unused land. It involves building a new section of canal to create an island. The project will also restore a part of the river for boats and create a new basin. The basin opened in October 2009. It will eventually connect to the River Rother with a lock.

Closing the Gap

By 2017, less than 9 miles (14 km) of the canal still needed to be restored to connect the two open sections. This part is challenging because new canal sections need to be built. This is to go around the houses in Killamarsh and to replace the Norwood Tunnel. The Chesterfield Canal Partnership has detailed plans for this work.

Engineers have looked at different routes for the canal through Killamarsh. The preferred route would be more attractive for boaters and cheaper to build. Both routes would go down into Nethermoor Lake and then climb back up to the original canal path.

The Norwood Tunnel cannot be reopened because parts of it have collapsed or been filled in. Engineers have proposed a new route that would go mostly on the surface. It would cross the site of an old colliery. This new route would involve building more locks and passing under the M1 motorway. However, plans for the new High Speed 2 (HS2) railway might change these ideas. One new idea is a shorter tunnel at the western end, going under both HS2 and the M1. This would save the need for several locks.

In 2020, the Trust submitted a plan for the remaining section within Chesterfield. HS2 initially opposed it, but in February 2021, an agreement was reached. This means both the canal restoration and the HS2 railway can be built.

Cool Canal Features

The boats that used to travel on the Chesterfield Canal were quite special. They were different from other canal boats because the canal was a bit isolated. Their cabins were below deck, and the boatmen always had homes on land. These boats didn't have the colorful decorations seen on other canals. They also didn't use engines; horses pulled them even into the 1950s! None of the original "cuckoo" boats survived. However, the last one was carefully measured before it was taken apart. This allowed the Canal Trust to build a new boat, called the Dawn Rose, using traditional methods. It was launched in April 2015.

Norwood Tunnel was a very long tunnel, about 2,884-yard-long (2,637 m). It was 9.25-foot-wide (2.82 m) and 12-foot-high (3.7 m). Most of it will remain closed because of damage and fill-ins.

Drakeholes Tunnel is a shorter tunnel, 154-yard (141 m) long. It also didn't have a towpath. It was built wider and higher than Norwood Tunnel to allow bigger boats to pass. Most of it was cut through solid rock.

Hollingwood Common Tunnel was a disused tunnel that led from a coalmine to the Chesterfield Canal. It was about 1+3⁄4 miles (2.8 km) long. Boats loaded with coal underground would travel through this tunnel.

There are early ideas for a new link from Killamarsh to the Sheffield and South Yorkshire Navigation along the River Rother. This would be called the Rother Link. It would let boats reach the Chesterfield Canal without using the tidal River Trent. It would also create a new circular route for boaters.

The towpath next to the canal has become a long walking and cycling path. It stretches for 46 miles (74 km) from Chesterfield to West Stockwith. It's called the "Cuckoo Way," named after the old canal boats. Parts of the towpath are also part of the Trans Pennine Trail cycle route.

The Chesterfield Canal made international news in 1978. A maintenance team was cleaning the canal when they pulled up a large chain with a wooden plug. Later, a whirlpool formed, and water started draining from the canal! It turned out the plug was an original feature designed to drain sections for repairs. The water drained safely into a nearby river. This event became a big story, even reported in Lloyd's List. These plugs were actually common on canals built at that time.

Images for kids

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |