Mersey and Irwell Navigation facts for kids

The Mersey and Irwell Navigation was an important waterway in North West England. It allowed boats to travel from the Mersey estuary all the way to Salford and Manchester. This was done by making the River Irwell and the River Mersey easier to navigate.

Workers built eight locks between 1724 and 1734. They also made new cuts in the rivers many times to improve the route. People used the navigation less and less from the 1870s. It was eventually replaced by the Manchester Ship Canal. Building the Ship Canal destroyed most of the Irwell part of the old navigation.

Contents

Building the Waterway

The idea to make the River Mersey and River Irwell navigable was first suggested in 1660. It was brought up again in 1712 by Thomas Steers. In 1720, plans for a special law were put forward. This law, called an Act of Parliament, was approved in 1721.

The Mersey & Irwell Navigation Company started building work in 1724. By 1734, medium-sized boats could travel from quays (docks) in Water Street, Manchester, to the Irish Sea. However, the navigation was only good for smaller ships. Sometimes, during dry spells or strong winds, there wasn't enough water for fully loaded boats.

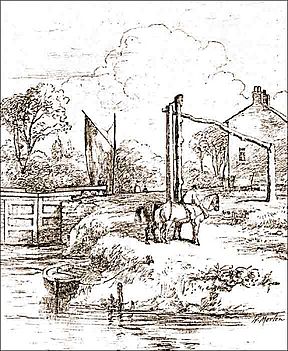

To help boats travel, eight weirs were built along the route. Weirs are like small dams that control water levels. Workers also made short cuts around shallow parts of the river. These cuts had locks, which are special gates that raise or lower boats between different water levels. Some tricky bends in the river were also straightened out.

The navigation was changed and improved many times. For example, a canal section called the Runcorn and Latchford Canal was added in 1804. This helped boats avoid a difficult part of the lower river. In 1740, the company built quays and warehouses along Water Street in Manchester. These were places for boats to load and unload goods.

In 1779, a group of business people from Manchester and Liverpool bought the navigation. They started making more improvements. They built a basin at Runcorn where boats could wait for the tide. An aqueduct was also built from Woolston Cut. This helped replace water that was lost from the locks.

Competition and Changes

Other new ways to transport goods soon appeared. The Bridgewater Canal was finished in 1776. Then, in 1830, the Liverpool & Manchester Railway opened. Both of these offered faster ways to move goods. This meant more competition for the Mersey and Irwell Navigation.

In 1844, the Bridgewater Canal Company bought the navigation for £550,800. By 1846, the Canal Company officially owned it. The company that ran the navigation was known by several names. These included "The Old Navigation," "Old Quay Company," and "Old Quay Canal."

Decline of the Waterway

In 1872, the navigation was sold again to the new Bridgewater Navigation Company for £1,112,000. But by this time, it was in bad shape. In 1882, people said it was "hopelessly choked with silt and filth." This means it was filled with so much mud and dirt that boats could barely use it. It was only open for 50-ton boats on 47 days out of 311 working days.

Economic problems grew worse in the mid-1870s. This period is sometimes called the Long Depression. The fees charged by the Port of Liverpool were very high. Also, the railway costs from Liverpool to Manchester were expensive. It was often cheaper to bring goods into England through Kingston upon Hull, on the other side of the country. This was even though Liverpool was only about 35 miles away.

To help Manchester's economy, people suggested building a ship canal. This would give the city direct access to the sea for its imports and exports.

The building of the Manchester Ship Canal destroyed large parts of the older Mersey and Irwell Navigation. Almost the entire Irwell section of the old route was removed. Only a short part upstream of Pomona Docks still exists today.

Further downstream, the Ship Canal followed a different path than the old navigation. The old navigation was still used as late as 1950 from Rixton Junction downstream.

The lower parts of the Ship Canal also destroyed a big section of the Runcorn to Latchford Canal. Only a short piece remains, connecting the navigation to the Canal near Stockton Heath. The Woolston New Cut, dug in 1821, can still be seen today, but it is completely dry. Woolston Old Cut, built in 1755, also still exists, but its lock is gone.

Design and Construction Details

Locks Along the Route

The Mersey and Irwell Navigation originally had eight locks. Each lock chamber was 13 feet wide and 65 feet long.

Throstles Nest Lock was the highest lock on the navigation. Mode Wheel lock came next. Lock 3 was at Barton upon Irwell, near James Brindley's first Barton Aqueduct. The remains of the lock island seem to be in the same spot as the island used for the swing aqueduct today. Stickins Lock followed, in a 600-yard cut. There were also locks named Holmes Bridge, Calamanco, Holmes Bridge, and finally Howley Tidal.

More locks were added as the route was improved over time. These included a new Stickins Lock and Sandywarps Lock. Butchersfield Locks were on a short cut called the Butchersfield Canal. Woolston New Lock was at the upper end of Woolston New Cut. Paddington Lock was at the lower end of Woolston New Cut. There were also Woolston Old Lock, Latchford, and Old Quay Sea Locks.

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |