John Kay (flying shuttle) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Kay

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait, said to be of John Kay in the 1750s, but probably of his son, "Frenchman" John Kay.

|

|

| Born | 17 June (N.S 28 June) 1704 Walmersley, Bury, Lancashire, England

|

| Died | c. 1779 France

|

| Nationality | English |

| Occupation | Inventor |

| Known for | Flying shuttle |

| Spouse(s) | Anne Holte |

| Children | Lettice, Robert (drop box inventor), Ann, Samuel, Lucy, James, John, Alice, Shuse, William, (and two other children who died in childhood) |

| Parent(s) | Robert Kay and Ellin Kay, née Entwisle |

John Kay (born June 17, 1704 – died around 1779) was an English inventor. His most important invention was the flying shuttle. This machine was a huge step forward for the Industrial Revolution. Sometimes, people confuse him with another inventor named John Kay, who invented a different machine called the "spinning frame."

Contents

Early Life and Inventions

John Kay was born on June 17, 1704, in a small village called Walmersley in Lancashire, England. His father, Robert, was a farmer who owned land. Sadly, John's father died before John was born.

John was the fifth of ten children. He was supposed to receive money and an education until he was 14. His mother taught him until she got married again.

Learning a Trade

John started learning to make parts for hand-looms, which are machines used for weaving cloth. He quickly learned the trade. He even designed a new metal part to replace the old natural ones. This new part became very popular.

After traveling around England selling his metal parts, he returned home. In 1725, John married Anne Holte. They had many children, including a daughter named Lettice and a son named Robert.

Back in his hometown, John kept inventing. In 1730, he patented a machine for making special threads used in weaving.

The Flying Shuttle Invention

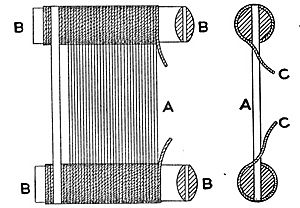

In 1733, John Kay received a patent for his most important invention. He called it a "wheeled shuttle" for the hand loom. Today, we know it as the "flying shuttle."

This invention made weaving much faster. It allowed the shuttle, which carries the thread, to move quickly across the loom. Before this, weaving wide cloth needed two workers. With the flying shuttle, only one person was needed.

Kay called it a "wheeled shuttle," but others called it the "fly-shuttle" or "flying shuttle." This was because it moved so incredibly fast. People said it moved "at a speed which cannot be imagined."

Facing Challenges

In 1733, Kay tried to start making his flying shuttles in a town called Colchester. He thought people would be happy about his invention. However, the weavers there worried about losing their jobs. They even asked the King to stop Kay's inventions.

The flying shuttle made weaving twice as fast. But the machines that made thread (spinning machines) couldn't keep up. This caused problems because there wasn't enough thread for all the fast looms.

Kay tried to improve his invention. He spent two years making the flying shuttle stronger and better. This was important because he faced many legal problems later on.

In 1738, Kay moved to Leeds. His biggest problem was collecting money from people who used his invention. They were supposed to pay him a small fee each year for each shuttle.

The Shuttle Club

Many manufacturers copied Kay's invention without paying him. Kay tried to sue them, but it was expensive. Instead of paying, the manufacturers formed a group called "the Shuttle Club." This club helped pay the legal costs for any member who was sued. Their plan was to copy his invention and avoid paying him. This almost made John Kay go broke.

In 1745, Kay and a partner patented a machine for weaving ribbons. They hoped to power it with a water wheel. But Kay's legal problems used up all his money. Poor and troubled, Kay had to leave Leeds and return to his hometown of Bury.

Kay kept inventing. He worked on a new way to make salt and improved spinning machines. But this made him unpopular with spinners in Bury. Also, as more people used the flying shuttle, the demand for cotton thread went up, and so did its price. People blamed Kay for this.

Life in France

John Kay had a difficult time in England. He couldn't make money from his inventions because people kept copying them. So, in 1747, he decided to move to France. He had never been there before and didn't speak French.

Government Support

In Paris, Kay talked with the French government. He wanted to sell them his invention. He eventually agreed to a payment of 3,000 French livres and a yearly payment of 2,500 livres. In return, he would give them his patent and teach them how to use the shuttle.

Kay kept the only rights to make the shuttles in France. He brought three of his sons to Paris to help him. He was careful about going to the areas where weaving was done, remembering the angry weavers in England. But he was convinced to go.

By 1753, the flying shuttle was widely used in France. Most of these new shuttles were copies, not made by Kay or his sons. John Kay tried to stop people from copying his work, but he wasn't successful. He started having arguments with the French authorities.

He briefly returned to England in 1756. It's said that his home in Bury was attacked by a mob in 1753, but he was probably in France at that time.

Kay found that things hadn't improved for him in England. By 1758, he was back in France, which became his new home. He did visit England at least two more times. In 1765, he asked the Royal Society of Arts in England to reward him for his inventions. But no award was ever given. He was in England again in 1773 but returned to France in 1774. He had lost his yearly payment from the French government.

Later Years

Kay offered to teach others if his payment was restored, but his offer was not accepted. He spent his last years developing and building machines for cotton makers in other French towns. He was busy with engineering and writing letters until 1779. However, he received very little money from the French government during these years. He became very poor.

His last known letter was in June 1779. In it, he listed his latest achievements and suggested more inventions. Since nothing more was heard from the 75-year-old Kay, it is believed he died later that year.

Legacy and Recognition

In Bury, John Kay is now seen as a local hero. There are pubs and gardens named after him. In 1908, a memorial sculpture to John Kay was put up in Bury town center. People felt that Bury "owed John Kay's memory an atonement" for how he was treated.

John Kay's son, Robert, stayed in England. In 1760, he invented the "drop-box." This allowed looms to use many flying shuttles at once, making it possible to weave cloth with different colored threads.

Another of John's sons, also named John, lived with his father in France. In 1782, he told Richard Arkwright about his father's problems. Arkwright used this story to show how difficult it was to protect inventions in England.

The artist Ford Madox Brown painted a picture of Kay and his invention in a famous mural in Manchester Town Hall.

See also

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |