Irish issue in British politics facts for kids

The issue of Ireland has been a big topic in British politics for hundreds of years. Britain's efforts to control Ireland, or parts of it, had a huge impact on British politics, especially in the 1800s and 1900s. Even though Ireland was somewhat independent (as the Kingdom of Ireland) until the late 1700s, it became part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in 1801.

In 1844, a future British Prime Minister, Benjamin Disraeli, described what he called the Irish Question:

A dense population, in extreme distress, inhabit an island where there is an Established Church, which is not their Church, and a territorial aristocracy the richest of whom live in foreign capitals. Thus you have a starving population, an absentee aristocracy, and an alien Church; and in addition the weakest executive in the world. That is the Irish Question.

The Great Famine from 1845 to 1851 caused over 1 million Irish people to die. Another million were forced to move, many to the United States. The British government's poor handling of the famine created deep distrust and anger. Many in Ireland felt that the government's policies, which allowed food to be exported from Ireland and kept wheat expensive, made the famine worse. They believed an independent government would have helped more.

In 1884, a law allowed many Catholics in Ireland to vote. Charles Stewart Parnell helped gather Catholic votes so that the Irish Parliamentary Party had a lot of power in the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Parnell wanted to bring back home rule for Ireland, meaning Ireland would govern itself. He used tactics that often caused problems in British politics. William Gladstone and his Liberal Party usually worked with Parnell to achieve Home Rule. However, this caused the Liberal Party to split, with some members forming the Liberal Unionist Party. This led to the Liberal Party becoming less powerful over time.

Home Rule was approved in 1914, but it was put on hold during the First World War. The issue was finally settled in 1921 by dividing Ireland. The larger, mostly Catholic part became the Irish Free State, which was almost independent. The smaller, mostly Protestant part, Northern Ireland, remained part of the United Kingdom. New problems, known as The Troubles, started in the 1960s. Catholics in Northern Ireland felt they were treated unfairly by the local government. This period of almost civil war lasted 30 years and greatly affected British politics. It ended with the Good Friday Agreement in 1998. This agreement set up a power-sharing government in Northern Ireland and was also a treaty between Ireland and the United Kingdom.

From 2017 onwards, Britain's relationship with Ireland caused new political issues, especially because of Brexit. Until late 2019, the British Parliament struggled to find a solution that would allow: an open border on the island of Ireland; no trade borders within the United Kingdom; and no British involvement in the European Single Market or the European Union Customs Union. The government eventually gave up on the second goal. They negotiated and signed the Northern Ireland protocol, which started in early 2021.

Contents

- Ireland in the 1700s: Changes and Rebellions

- Ireland in the Early 1800s: Famine and Political Change

- Ireland from 1868 to 1900: Home Rule and Political Splits

- Ireland from 1900 to 1922: War, Partition, and Independence

- Ireland from 1923 to 2015: Changing Relationships

- Ireland from 2016 to 2019: Brexit and the Border

- Ireland from 2020 Onwards: The Northern Ireland Protocol

- See also

Ireland in the 1700s: Changes and Rebellions

For most of the 1700s, Ireland was fairly calm and didn't play a big role in British politics. Between 1778 and 1793, many laws that limited Catholics were removed. These laws had restricted their worship, land ownership, education, and jobs. Wealthy Irish Catholics were allowed to vote in 1793. The main restriction left was that Catholics could not be members of Parliament. Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger actively supported these changes. However, King George III, a strong Protestant, was worried by the reforms. He refused to allow Catholics into Parliament, which led Pitt to resign in 1801.

Even though the Catholic majority was getting more rights, Ireland's economy, politics, society, and culture were mostly controlled by Anglican landowners. These landowners made up the Protestant Ascendancy. There was also a large Presbyterian population in the north-east. They felt left out by the Anglican established church. After 1790, they began to lead the way in developing Irish nationalism.

The 1798 Rebellion: A Fight for Change

The 1798 Rebellion was a major uprising against British rule in Ireland. The main group behind it was the Society of United Irishmen. This was a republican revolutionary group inspired by the ideas of the American and French revolutions. It was first formed by Presbyterian radicals who were angry about being excluded from power by the Anglican church. Many Catholics later joined them.

After some early successes, especially in County Wexford, the rebellion was put down by government forces and the British Army. Between 10,000 and 50,000 people died. A French army arrived in County Mayo in August to help the rebels. Even though they won a battle at Castlebar, they were eventually defeated too. After the rebellion, the Acts of Union 1800 were passed. This law combined the Parliament of Ireland with the Parliament of the United Kingdom.

Ireland in the Early 1800s: Famine and Political Change

The agreement that led to the Act of Union promised to give Catholics more rights and remove the Penal Laws in Ireland. However, King George III stopped this, saying his coronation oath required him to defend the Anglican Church. A campaign led by Roman Catholic lawyer Daniel O'Connell eventually led to Catholic Emancipation in 1829. This allowed Catholics to sit in Parliament. O'Connell then tried, but failed, to get the Acts of Union repealed.

The Great Famine: A Time of Suffering

When a potato blight hit Ireland in 1846, many poor farmers lost their main food source. This happened because other crops were grown to be sold and sent to Great Britain. People and charities raised a lot of money for help. However, the government did not do enough. They believed in laissez-faire policies, meaning they thought the economy should be left alone. Also, the Corn Laws made wheat too expensive to import. These factors turned the problem into a disaster. Many farm laborers died or moved away, in what became known as 'The Irish Potato Famine' in Britain and the Great Hunger in Ireland.

The famine and its memory forever changed Ireland's population, politics, and culture. Those who stayed and those who left never forgot it. The government's poor handling of the famine became a key reason for Irish nationalist movements. Relations between Irish Catholics and the British Crown became even worse, increasing ethnic and religious tensions. Republicanism, a movement for a fully independent Irish republic, also grew stronger.

Ireland from 1868 to 1900: Home Rule and Political Splits

The first time Benjamin Disraeli was Prime Minister in 1868 was short. It was mostly about the heated debate over the Church of Ireland. This was a Protestant church linked to the Anglican Church of England. Even though three-quarters of Ireland was Roman Catholic and 90% were nonconformist (not Anglican), the Church of Ireland was still the official church. It was paid for by tithes (direct taxes). Catholics and Presbyterians were angry about this. The Irish Church was eventually separated from the state by Gladstone's Irish Church Act 1869. This caused disagreements among the Conservatives.

The Home Rule Movement: A Push for Self-Government

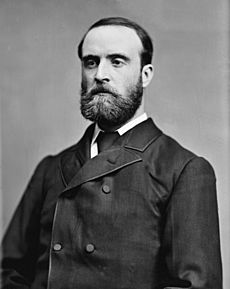

Most Irish people who could vote elected Liberals and Conservatives, who belonged to the main British political parties. A smaller group also elected Unionists, who wanted Ireland to stay part of the United Kingdom. A former lawyer named Isaac Butt started a new, moderate nationalist movement called the Home Rule League in the 1870s. After Butt died, the Home Rule Movement, also known as the Irish Parliamentary Party, became a major political force. This happened under the leadership of William Shaw and especially Charles Stewart Parnell.

Parnell came from a wealthy Anglo-Irish Anglican family. He became a Member of Parliament in 1875. He worked to change land laws and became the leader of the Home Rule League in 1880. Parnell worked independently from the Liberals. He gained a lot of influence by balancing different political and economic issues. He was also very skilled at using parliamentary rules. His party used long speeches to delay the Protection of Persons and Property Act 1881 for seven weeks. He was put in prison in 1882 but was released after he agreed to stop violent actions.

Balance of Power: Irish Influence in Parliament

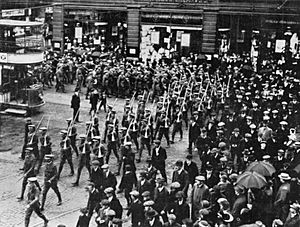

From 1885 to 1915, the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP), led by Parnell, often held the balance of power in the British Parliament. This meant they could decide which of the main parties, Liberal or Conservative, would form the government. They used this power to get benefits for Ireland. For example, the Conservative government of Lord Salisbury passed the Purchase of Land (Ireland) Act 1885 (the "Ashbourne Act") in exchange for the IPP's support.

Parnell's movement wanted "Home Rule." This meant Ireland would manage its own internal affairs while still being part of the United Kingdom. This was different from O'Connell, who wanted complete independence with only the monarch shared. Liberal Prime Minister Ewart Gladstone introduced two Home Rule Bills (1886 and 1893). However, neither became law, mainly because the House of Lords opposed them. The issue divided Ireland. A large unionist minority, mostly in Ulster, opposed Home Rule. They worried that a Catholic-Nationalist parliament in Dublin would be controlled by the Catholic Church and harm Protestantism. They also feared it would hurt the economy, especially industry in Ulster. Gladstone spent the last part of his career trying to pass a Home Rule bill, but he failed both times.

The Liberal Party Splits Over Ireland

In 1886, the ruling Liberal Party split because of Gladstone's Home Rule plans. Some Liberals believed that Gladstone's bill would eventually lead to Ireland becoming fully independent and the breakup of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. They could not accept this. They called themselves "Liberal Unionists" because they wanted to defend the Union. At first, they didn't think their split from the Liberals would be permanent. However, they later joined the Conservative Party, creating the Conservative and Unionist Party. The Liberal Party, which had been very powerful in Britain for many years, became much weaker over time.

Fenianism: A More Radical Path

Some people were not satisfied with Home Rule under British government. From the mid-18th century to the late 19th century, the Fenians carried out violent actions against British rule from time to time. One notable event for British politics was when a group called the Irish National Invincibles, a part of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, assassinated the British Chief Secretary for Ireland Lord Frederick Cavendish and his chief civil servant in 1882. This event is known as the Phoenix Park Murders.

Ireland from 1900 to 1922: War, Partition, and Independence

Passing Home Rule: A Difficult Journey (1910–1914)

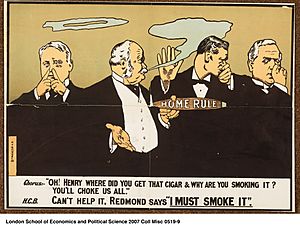

After the 1910 elections, the Liberal Party was a minority party. They needed the support of Irish Members of Parliament, led by John Redmond. To get Irish support for their budget and a new law about Parliament, Prime Minister Asquith promised Redmond that Irish Home Rule would be their top priority. This turned out to be much more complicated and time-consuming than expected.

Supporting self-government for Ireland had been a Liberal Party goal since 1886. However, Asquith had not been very enthusiastic about it. After 1910, though, Irish votes were needed for the Liberals to stay in power. Keeping Ireland in the United Kingdom was the stated goal of all parties. The Irish Nationalists, as part of the group that kept Asquith in office, had the right to push for their Home Rule plans and expect support from the Liberal and Labour parties. The Conservative and Unionist Party, with strong support from the Protestant Orange Order, strongly opposed Home Rule.

The bill for Home Rule, introduced in April 1912, applied to all of Ireland and did not include any special status for Protestant Ulster. Neither dividing Ireland nor giving Ulster special status was likely to satisfy everyone. The self-government offered by the bill was very limited, but Irish Nationalists supported it, hoping Home Rule would come step by step. Conservatives and Irish Unionists opposed it. Unionists began preparing to use force if necessary, which led nationalists to do the same. The Unionists were generally better funded and more organized. In April 1914, the Ulster Volunteers smuggled in 25,000 rifles and bayonets and over 3 million rounds of ammunition from Germany.

As the situation became more serious, with the Ulster Volunteers openly training, Churchill arranged for a Royal Navy squadron to sail near Belfast. This was done without first discussing it with the Cabinet. Unionist leaders thought Churchill and War Secretary John Seely were trying to provoke them into an action that would allow Ulster to be put under military rule. Asquith canceled the move two days later.

The Parliament Act: Limiting the Lords' Power

After the Liberal split in 1886, the House of Lords had a huge Conservative-Unionist majority. When the Liberal Party tried to pass important welfare reforms, disagreements between the two houses of Parliament were sure to happen. Between 1906 and 1909, several important laws were weakened or rejected by the Lords. For example, the Education Bill of 1906 was changed so much by the Lords that it became a different bill, and the Commons dropped it. This led to a resolution in the House of Commons on June 26, 1907, proposed by Liberal Prime Minister Henry Campbell-Bannerman, saying that the Lords' power should be reduced.

In 1909, hoping to force an election, the Lords rejected the "People's Budget" proposed by David Lloyd George. This action, according to the Commons, was "a breach of the constitution and a usurpation of the rights of the Commons." The Lords suggested that the Commons prove in an election that the bill truly represented the will of the people. The Liberal government tried to do this through the January 1910 general election. Their number of MPs dropped a lot, but they still had a majority with the help of the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) and Labour MPs. The IPP saw the Lords' continued power as a problem for getting Home Rule. After the election, the Lords gave in on the budget, and it passed on April 28.

The Lords now faced the possibility of a Parliament Act, which had strong support from the Irish Nationalists. However, Home Rule for Ireland was the main point of disagreement. Unionists wanted to make an exception for "constitutional" or "structural" bills, like Home Rule, so the Parliament Act wouldn't apply to them. The Liberals supported an exception for bills about the monarchy, but not Home Rule.

The government threatened another election if the Parliament Act was not passed. They followed through on this threat when the Lords continued to oppose it. The December 1910 general election showed little change from January. King George V was asked if he would create enough new peers (members of the House of Lords) to pass the bill, which he said he would only do if necessary. This would have meant creating over 400 new Liberal peers. The King did, however, demand that the bill be rejected at least once by the Lords before he would intervene. Two changes made by the Lords were rejected by the Commons, and opposition to the bill showed little sign of stopping. This led Asquith to announce the King's intention to create enough new peers to overcome the majority in the House of Lords. The bill finally passed in the Lords by 131 votes to 114, with many abstentions.

The Government of Ireland Act 1914: Home Rule on Hold

The Parliament Act meant that Unionists in the House of Lords could no longer completely block Home Rule. They could only delay it by two years. Asquith decided to wait until the bill's third passage through the Commons to make any concessions to the Unionists, believing they would then be desperate for a compromise. Historian Roy Jenkins thought that if Asquith had tried for an earlier agreement, it wouldn't have worked, as many of his opponents wanted a fight. Edward Carson, the leader of the Irish Unionists in Parliament, threatened a revolt if Home Rule was passed. The new Conservative leader, Bonar Law, warned Protestants in Ulster against "Rome Rule," meaning domination by the island's Catholic majority. Many who opposed Home Rule felt that the Liberals had broken the Constitution by pushing through major changes without a clear public vote.

The strong feelings about the Irish question were a contrast to Asquith's calm approach. He called the possible division of County Tyrone, which had a mixed population, "an impasse, with unspeakable consequences." As the Commons debated the Home Rule bill in late 1912 and early 1913, unionists in northern Ireland organized themselves. There was talk of Carson declaring a Provisional Government and the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) being built around the Orange Lodges. However, only Churchill in the cabinet seemed worried about this. These forces, who said they were loyal to the British Crown but were getting well-armed with smuggled German weapons, prepared to fight the British Army. But Unionist leaders were confident that the army would not help force Home Rule on Ulster.

As the Home Rule bill waited for its third passage through the Commons, the Curragh incident happened in April 1914. About sixty army officers, led by Brigadier-General Hubert Gough, said they would rather be fired than obey orders to move against Ulster. With unrest spreading to army officers in England, the Cabinet tried to calm the officers. Asquith wrote a statement reminding officers of their duty to obey lawful orders but claiming the incident was a misunderstanding. War minister John Seely then added an unauthorized promise, signed by General John French (the head of the army), that the government had no intention of using force against Ulster. Asquith rejected this addition and demanded Seely and French resign. Asquith took control of the War Office himself until the Great War began in 1914.

On May 12, Asquith announced that Home Rule would pass its third reading in the Commons (which happened on May 25). However, there would also be an amending bill to make special arrangements for Ulster. The Lords made changes to this amending bill that Asquith found unacceptable. Since the Parliament Act couldn't be used on the amending bill, Asquith agreed to meet other leaders at an all-party conference on July 21 at Buckingham Palace, led by the King. When no solution was found, Asquith and his cabinet planned more concessions to the Unionists. But this was stopped when the crisis in Europe led to war. In September 1914, the Home Rule bill became law (as the Government of Ireland Act 1914) but was immediately suspended. It never actually went into effect.

World War, Partition, and Irish Independence

When the First World War started in August 1914, Asquith and Redmond, the leader of the Irish Nationalist Party, agreed that the Home Rule Bill would become law, but it would be put on hold for the war. This was done. Most Irish people supported this solution at the time. Ireland was also at war with Germany, and most Unionist and Nationalist volunteers joined the new British Army. However, Republican newspapers openly supported violence, spoke against joining the army, and strongly promoted the views of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). When one paper was shut down, another took its place. Weapons were smuggled in, paid for by money raised in the United States. The IRB asked Germany to make Irish freedom a war goal. Germany promised to send 20,000 rifles and machine guns, ammunition, and explosives with Sir Roger Casement. London knew trouble was coming but decided to be very careful. They feared that a full crackdown on the IRB would have very negative effects in the United States, which remained neutral until April 1917. Instead, London decided to trust Redmond and the established Irish Parliamentary Party.

The Easter Rising: A Bold Attempt for Freedom

A "Irish Republic" was declared in Dublin at Easter 1916. This event is known as the Easter Rising. British attention was focused on the Western Front, where the Allied armies were struggling. The uprising was very poorly organized and led. It was crushed after six days of fighting. 134 government soldiers and 285 rebels died. When the rebels surrendered, people in Dublin booed them. Newspapers called their actions foolish, useless, cruel, and crazy. Most of the leaders were tried by military court and executed. Historians Clayton Roberts and David Roberts argue that:

the theme of redemption in the absence of socialist dogmas allowed the Catholic hierarchy and its worshipers to see these men as heroically devoted to Ireland.... Militarily the rebellion was foolish, futile, and bungled; theatrically it was brilliant and moving, a tragic act of singular dramatic power. It released the nationalist feeling that forms one of the most powerful forces in modern history.

After the Rising, many Nationalists across Ireland left the Irish Parliamentary Party. They started supporting Sinn Féin, the Republican party that demanded complete independence. In 1917, Prime Minister David Lloyd George tried to introduce Home Rule again. He failed because he also desperately needed soldiers and forced conscription (drafting people into the army) on Ireland. This caused the conscription crisis. As a result, in the 1918 Irish general election, Sinn Féin won most of the Irish seats. However, their MPs refused to take their seats in the British Parliament. Instead, they set up the First Dáil (parliament) in Dublin, announced an independent Irish Republic, and declared war against the British government, which still controlled Ireland.

The government in London had three choices: put the 1914 Home Rule Act into effect with a change to exclude Ulster; cancel it; or replace it with new laws. They chose the third option. The Government of Ireland Act 1920 divided Ireland into Southern Ireland and Northern Ireland. This policy had wide support in Northern Ireland, England, Wales, and Scotland, from both Conservatives and Liberals. The small new Labour Party opposed the division.

The Irish War of Independence and the Anglo-Irish Treaty

The Irish War of Independence was fought between the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and British forces from January 1919 to July 1921. The IRA, led by Michael Collins, had about 3,000 rebels. They used asymmetric warfare (guerrilla tactics) against British forces, which included the Black and Tans and the Auxiliary Division. In 1920, at the height of the war, Prime Minister David Lloyd George introduced the Government of Ireland Act 1920. This law divided Ireland into Southern Ireland and Northern Ireland starting in May 1921.

In December 1921, the Irish Republic and the United Kingdom agreed to the Anglo-Irish Treaty to end the war. This treaty created a largely independent dominion called the Irish Free State, replacing the (failed) Southern Ireland. Meanwhile, Northern Ireland (Ulster), with its own local government, remained part of the United Kingdom. The majority of the Dáil (Irish Parliament) approved the treaty, but De Valera, the President of the Dáil, rejected it. De Valera led a civil war in Ireland but was defeated. The treaty with Britain went into effect, and Northern Ireland remained with the UK.

1921–1922: Northern Ireland and the Irish Free State are Formed

The Irish issue became easier to solve when the Conservative Party became more flexible about keeping all of Ireland united with Great Britain. New factors included Lloyd George's good negotiating skills, new and more flexible Conservative leaders, and less strong opposition after most of Ulster was guaranteed to stay in the UK. Also, people generally disapproved of using force. The Treaty of 1921 was not completely in line with the Labour Party's Irish policy. However, the two Labour MPs supported it in debate, as did the Labour press. Labour wanted the Irish problem to end so Britain could focus on issues related to social classes. With the Irish Free State largely independent and Northern Ireland securely part of the UK, the Irish issue became much less important in British politics.

Ireland from 1923 to 2015: Changing Relationships

Irish Free State Becomes Ireland

In 1937, taking advantage of the Edward VIII abdication crisis and the Statute of Westminster 1931, the Irish Free State moved further away from the United Kingdom. It changed its name to "Ireland" (or, in Irish, "Éire"). A trade war happened in the 1930s. As part of the agreement in 1938, the British were no longer allowed access to three naval ports. Ireland declared itself neutral in the Second World War. In 1948, Ireland declared itself a republic and left the British Commonwealth.

Britain's political interest in this part of the island officially ended when it passed the Ireland Act 1949. However, the two countries worked together, formally and informally, to try to solve the Troubles in Northern Ireland. The (failed) Anglo-Irish Agreement (treaty) of 1985 and the British-Irish treaty part of the Good Friday Agreement of 1998 are the most important examples of this cooperation.

Northern Ireland and The Troubles

The Government of Northern Ireland from 1921 was shaped by Protestant leaders like Sir Edward Carson and Sir James Craig. This government oversaw social, cultural, political, and economic unfairness against the Catholic minority. Northern Ireland became, in the words of David Trimble, a "cold place for Catholics." From the civil rights marches of 1968 through years of violence between communities, known as "The Troubles," until the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, Northern Ireland was in a state of near civil war. This violence sometimes spread to Great Britain, including the assassination of Airey Neave and the attempted assassination of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and her ministers.

Ireland from 2016 to 2019: Brexit and the Border

Balance of Power Again: The DUP's Influence

At the 2017 United Kingdom general election, the Conservative government lost its overall majority. A Northern Irish political party, the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), held the balance of power. They negotiated good financial terms for Northern Ireland in exchange for supporting the government on certain issues. This agreement did not include supporting the Government's Brexit plans. The DUP rejected Prime Minister Theresa May's draft agreement of December 2017. They also voted against the government's 2018 draft withdrawal agreement and the proposal for a UK/EU customs union. (Either of these would have avoided the need for the Northern Ireland Protocol in the 2020 withdrawal agreement, which was negotiated after the DUP lost its balance of power following the 2019 election.)

Brexit and the Irish Border: A Complex Challenge

After Brexit, the Republic of Ireland–United Kingdom border on the island of Ireland would be the only major external EU land border between the United Kingdom and the European Union. This could have serious effects on Northern Ireland if there were a hard border (with customs checks and controls). Both the UK and the EU made avoiding a 'hard border' a top priority in the Withdrawal Agreement. The Irish government, in particular, saw an open border on the island of Ireland as a key part of the Good Friday Agreement.

The British government faced a difficult choice among three goals: (a) an open border on the island; (b) no border between Northern Ireland and Great Britain; and (c) no British participation in the European Single Market and the European Union Customs Union. The 'backstop' plan would have solved this by keeping the UK in the Single Market until a way to have an 'invisible' border in Ireland could be found. Many Brexit-supporting Conservative and DUP MPs opposed the Northern Ireland backstop because it didn't have a clear end date. They worried it could tie the UK to many EU rules forever. The EU, especially the Irish Government, saw a temporary guarantee as useless. They doubted that 'alternative arrangements' for the Irish border would be found soon.

Ireland from 2020 Onwards: The Northern Ireland Protocol

The Northern Ireland Protocol: New Rules and Ongoing Discussions

At the 2019 United Kingdom general election (December 2019), the Conservative Party won a large majority. They no longer needed the DUP's support. In 2020, Prime Minister Boris Johnson finished negotiations on the Brexit withdrawal agreement. This agreement solved the difficult choice by including the Northern Ireland Protocol. This protocol set up controls on goods moving from Great Britain to Northern Ireland, despite DUP opposition. Within six months of signing the agreement, the Johnson government tried to renegotiate it. As of September 2021, the ongoing disagreement over the arrangements for Northern Ireland threatened other parts of the relationship between the UK and the EU.

In 2022, Rishi Sunak became the first prime minister since 2007 to attend a British-Irish Council summit. He repeated his commitment to bringing back the Northern Ireland Executive (the local government) and said he was "determined to deliver" power-sharing. DUP leader Sir Jeffrey Donaldson said that any outcome of UK-EU talks on the protocol must have support from both communities in Northern Ireland.

See also

- All-for-Ireland League, 1906–1918

- Cork Free Press 1910 – 16

- History of Ireland (1801-1923)

- History of Northern Ireland

- Home Rule Act 1914

- Ireland and World War I

- Irish Convention

- Irish Home Rule movement, 1870–1921

- Irish Land Acts, 1870–1901

- Irish Land and Labour Association, 1890s

- Irish Parliamentary Party, IPP, 1874–1918

- Irish Reform Association, `1904-5

- Irish Republican Army

- Irish nationalism

- Land Conference, 1902

- Michael Davitt, 1846–1906

- National Volunteers

- No Rent Manifesto, 1881

- Plan of Campaign, 1886–91

- Unionism in Ireland

- United Irish League, 1898-1920s

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |