Bonar Law facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

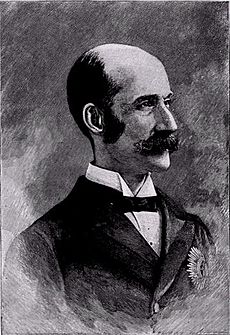

Bonar Law

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

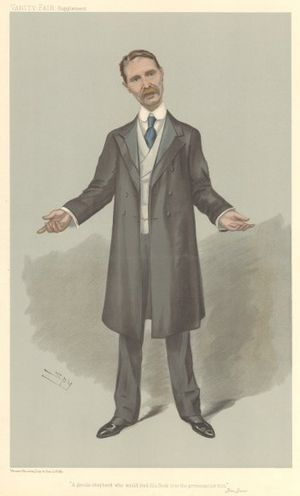

Law c. 1920

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister of the United Kingdom | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 23 October 1922 – 20 May 1923 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | George V | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | David Lloyd George | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Stanley Baldwin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leader of the Conservative Party | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 23 October 1922 – 28 May 1923 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chairman | Sir George Younger, Bt | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Vacant | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Stanley Baldwin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 10 December 1916 – 21 March 1921 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chairman |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Arthur Balfour | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Vacant | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leader of the House of Commons | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 23 October 1922 – 20 May 1923 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | Himself | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Austen Chamberlain | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Stanley Baldwin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 10 December 1916 – 23 March 1921 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | David Lloyd George | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | H. H. Asquith | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Austen Chamberlain | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 10 January 1919 – 1 April 1921 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | David Lloyd George | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | The Earl of Crawford | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Austen Chamberlain | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chancellor of the Exchequer | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 10 December 1916 – 10 January 1919 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | David Lloyd George | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Reginald McKenna | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Austen Chamberlain | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Secretary of State for the Colonies | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 25 May 1915 – 10 December 1916 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | H. H. Asquith | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Lewis Harcourt | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Walter Long | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leader of the Opposition | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 13 November 1911 – 25 May 1915 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | George V | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | H. H. Asquith | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Arthur Balfour | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Sir Edward Carson | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parliamentary Secretary to the Board of Trade | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 11 July 1902 – 5 December 1905 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | Arthur Balfour | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | The Earl of Dudley | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Hudson Kearley | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born |

Andrew Bonar Law

16 September 1858 Rexton,, Colony of New Brunswick (now Canada) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 30 October 1923 (aged 65) London, England |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | Westminster Abbey | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nationality | British | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Conservative | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other political affiliations |

Unionist | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse |

Annie Robley

(m. 1891; died 1909) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 6, including Richard | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Profession | Iron merchant | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

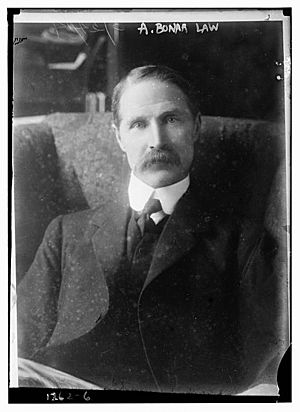

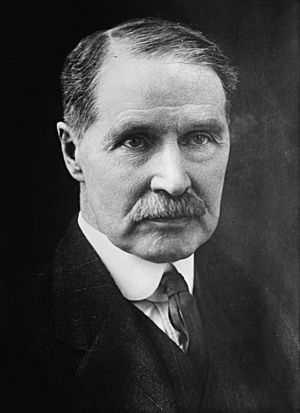

Andrew Bonar Law (born September 16, 1858 – died October 30, 1923) was a British politician from the Conservative Party. He served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from October 1922 to May 1923.

Bonar Law was born in what is now New Brunswick, Canada. His family had roots in Scotland and Northern Ireland. He moved to Scotland in 1870 when he was 12. He left school at 16 to work in the iron business and became quite wealthy by age 30. He entered the House of Commons in 1900, which was a bit late for a top politician.

He became a junior minister in 1902. In 1911, he was chosen to lead the Conservative Party, even though he had never been in the Cabinet before. He became leader when the other main candidates stepped aside to avoid splitting the party.

As the leader of the Conservative Party, Bonar Law focused on changing trade rules (called tariff reform) and opposing Irish Home Rule. His efforts helped turn the Liberal Party's plan for Irish Home Rule into a long struggle. This fight was eventually stopped by the start of World War I.

Bonar Law first joined the Cabinet as Secretary of State for the Colonies in 1915 during World War I. He later became Chancellor of the Exchequer in David Lloyd George's government. He resigned in 1921 due to poor health. In 1922, he became party leader again and then Prime Minister. His short time as Prime Minister included talks with the United States about Britain's war debts. He resigned in May 1923 because he was very ill with throat cancer and died later that year. He was one of the shortest-serving prime ministers in British history.

Contents

Early Life and School

Andrew Bonar Law was born on September 16, 1858, in Kingston (now Rexton), New Brunswick, Canada. His father, James Law, was a minister. His mother, Eliza Kidston Law, had Scottish and Irish family. At the time, New Brunswick was a separate colony, not yet part of Canada.

His mother wanted to name him after a preacher she admired, but his older brother was already named Robert. So, he was named after Andrew Bonar, a writer about that preacher. His family and close friends always called him Bonar, never Andrew. He later started signing his name as A. Bonar Law, and the public also called him Bonar Law.

His father, James Law, was a minister for small towns and traveled a lot. To earn more money, he bought a small farm. Bonar helped on the farm with his brothers and sister. Bonar did well in school and was known for his excellent memory.

After his mother died in 1861, her sister Janet came from Scotland to care for the children. When his father remarried in 1870, Janet decided to return to Scotland. She suggested that Bonar Law come with her because her family was wealthier. This would give Bonar a better chance in life. Both Bonar and his father agreed. Bonar never returned to Kingston.

Bonar Law went to live with his aunt Janet in Helensburgh, near Glasgow. Her brothers owned a family bank called Kidston & Sons. It was expected that Bonar would inherit the business or work there when he grew up.

He first attended Gilbertfield House School in Hamilton. In 1873, at age 14, he moved to the High School of Glasgow. His good memory helped him in languages like Greek, German, and French. He also started playing chess and became a very good amateur player. Even though he was good at school, it became clear he was better suited for business than for university. At 16, Bonar Law left school to work as a clerk at Kidston & Sons.

Business Life

At Kidston & Sons, Bonar Law earned a small salary. The idea was that he would learn about business. In 1885, the Kidston brothers decided to retire and merge their company with the Clydesdale Bank.

This merger would have left Bonar Law without a job. But the brothers found him a position with William Jacks, an iron merchant who was starting a political career. The Kidston brothers lent Bonar Law money to buy a share in Jacks' company. Since Jacks was not very active in the company, Bonar Law became the main manager. He worked long hours and made the company one of the most successful iron merchants in Glasgow.

During this time, Bonar Law continued to learn on his own. He attended lectures at Glasgow University and joined a debating club. This helped him improve his speaking skills, which were very useful in politics later.

By age 30, Bonar Law was a successful businessman. He had time for hobbies like chess, golf, tennis, and walking. In 1888, he moved into his own home with his sister Mary as his housekeeper.

In 1890, Bonar Law met Annie Pitcairn Robley. They married on March 24, 1891. Not much is known about his wife, as most of her letters are lost. She was well-liked, and her death in 1909 deeply affected Bonar Law. He never remarried. They had six children. Sadly, his two eldest sons, Charlie and James, were killed fighting in World War I in 1917. His youngest son, Richard, later became a Conservative politician.

Starting in Politics

In 1897, Bonar Law was asked to become a candidate for the Conservative Party in a parliamentary election. He chose to run for the seat of Glasgow Blackfriars and Hutchesontown. This area usually voted for the Liberal Party.

The election was expected in 1902, but the Second Boer War caused an early election in 1900. This election was known as the "khaki election." The campaign was tough, but Bonar Law impressed people with his speeches. On October 4, he won the election with a majority of 1,000 votes. He then stopped his active work at Jacks and Company and moved to London.

At first, Bonar Law found Parliament slow compared to his fast-paced business life. He later learned to be patient. On February 18, 1901, he gave his first speech. He used his excellent memory to quote past speeches by his opponents, showing how they had changed their views. This speech caught the attention of Conservative leaders.

Trade Rules and Reforms

Bonar Law became known for his views on tariff reform. This was about putting taxes (tariffs) on goods imported into Britain. The idea was to raise money and protect British industries. This issue divided British politics.

Bonar Law gave a major speech on April 22, 1902. He argued that tariffs on goods from outside the British Empire would be a good idea. He used his business experience to explain that tariffs might not necessarily raise the cost of living, as some argued. His strong memory helped him correct opponents who claimed he misquoted them.

Because of his business experience and speaking skills, Bonar Law was offered a position as Parliamentary Secretary to the Board of Trade in August 1902. His job was to help the head of the Board of Trade.

At this time, Joseph Chamberlain, a leading politician, strongly supported tariff reform. He wanted an Empire-wide system of tariffs to protect Imperial economies and unite the British Empire. This idea split the Conservative Party into two groups: those who supported free trade and those who supported Chamberlain's tariffs.

Bonar Law was a strong supporter of tariff reform. He focused on practical goals like reducing unemployment. He worked very hard in Parliament, often speaking in the House of Commons and debating against famous speakers like Winston Churchill. His speeches were known for being clear and sensible. Despite his efforts, the Conservative leader, Arthur Balfour, could not keep the party united. Balfour resigned in December 1905, and the Liberal Party formed a new government.

In Opposition

The new Prime Minister, Henry Campbell-Bannerman, immediately called an election. Bonar Law lost his seat in the 1906 general election. However, he was so important to the Conservatives that they quickly found him another seat in Dulwich. He won a special election there and returned to Parliament.

In 1906, Joseph Chamberlain suffered a stroke and had to retire. His son, Austen Chamberlain, took over as leader of the tariff reformers. Bonar Law joined the Shadow Cabinet as the main spokesperson for tariff reform. The death of his wife in 1909 made him work even harder, using his political career to cope with his loneliness.

The People's Budget and the House of Lords

In 1909, the Liberal government introduced the "People's Budget." This budget aimed to raise money through taxes to fund social programs. Usually, the House of Lords (the upper house of Parliament) does not reject money bills. But in this case, the Lords, who were mostly Conservative, rejected the budget. This caused a major constitutional crisis.

The Liberals called a general election in January 1910. Bonar Law campaigned for other Conservative candidates. He won his own seat with a larger majority. The election resulted in no single party having a clear majority. The Liberals stayed in power with the support of the Irish Parliamentary Party. The budget was passed a second time and then approved by the House of Lords.

However, the crisis showed a problem: should the House of Lords be able to reject bills passed by the House of Commons? The Liberal government introduced a bill to limit the Lords' power. This bill would prevent the Lords from stopping money bills and would force them to pass any bill that the Commons passed three times.

The Conservatives opposed this bill. Bonar Law focused on the issue of tariff reform. Some Conservatives wanted to drop tariff reform, but Bonar Law argued that it was important for the party.

Secret meetings were held to discuss the House of Lords issue. Bonar Law was one of the few people aware of these secret talks. The talks failed, and another general election was called in December 1910.

December 1910 General Election

In the December 1910 election, the Conservatives decided to have a strong supporter of tariff reform run in a difficult seat. Bonar Law was chosen for Manchester North West. He lost this election, but his strong campaign made him a "genuine Conservative hero." He later said that this defeat helped him more in the party than many victories.

In 1911, Bonar Law was elected in a special election for the safe Conservative seat of Bootle. The Liberals passed the Parliament Act 1911, which limited the power of the House of Lords. Bonar Law supported this, as it meant the Lords could still delay bills, which might help against Irish Home Rule.

Leader of the Conservative Party

On June 22, 1911, Bonar Law was made a Privy Councillor. This showed his importance in the Conservative Party. The previous leader, Arthur Balfour, had become unpopular. Many Conservatives felt his leadership was why they lost elections.

Balfour eventually resigned on November 7, 1911. Bonar Law, Walter Long, and Austen Chamberlain were the main candidates to replace him. At first, Bonar Law had less support. But Long and Chamberlain withdrew to avoid splitting the party. So, on November 13, Bonar Law became the leader of the Conservative Party. This was unusual because he had never been in the Cabinet before.

As leader, Bonar Law worked to improve the party. He chose younger, more popular people for important roles. He also used his business skills to reorganize the party, improving relations with the press and local groups. He also raised a lot of money for the next election.

In 1912, he united the Conservative and Liberal Unionist parties. From then on, they were called "Unionists" until 1922.

Bonar Law also introduced a new, tougher style of speaking in Parliament. This was different from the previous leader's style. He didn't always enjoy being so harsh, but it helped unite the divided Conservatives.

Social Policy

When Bonar Law became leader, the party's social policy was complicated. He said the party would stick to its principles. He largely avoided the issue of women's suffrage, letting party members vote as they wished. He was also not very enthusiastic about social reforms (laws to help the poor). He believed this was more of a Liberal issue.

In his first major speech as leader on January 26, 1912, he listed his main concerns:

- Criticizing the Liberal government for not holding an election on Home Rule for Ireland.

- Supporting tariff reform.

- Promising that the Conservatives would not let the Ulster Unionists be forced into an unfair Home Rule bill.

Both tariff reform and the issue of Ulster (part of Ireland) became central to his political work.

More Tariff Reform

After more discussions with his party, Bonar Law decided to support the full tariff reform plan, including taxes on imported food. He argued that avoiding food duties would split the party. He also pointed out that Canada, an important colony, would not agree to tariffs without British support for food duties.

Bonar Law decided to announce the change in policy at a party conference in November 1912. Lord Lansdowne made the announcement. He said that since the government had not held a vote on Home Rule, the promise to hold a vote on tariff reform was no longer valid. He promised that when the Conservatives came to power, they would be free to deal with tariffs as they saw fit. Bonar Law supported this.

However, many party members were not happy about this change. Bonar Law had not consulted them. He believed his approach was correct, but he knew it was causing problems within the party. He even considered resigning if the party could not agree.

Eventually, a compromise was reached, known as the January Memorial. Many Conservative MPs signed it, supporting Bonar Law and his policies. Bonar Law then published an open letter on January 13, 1913. He offered a compromise: food duties would not be voted on in Parliament until after a second election where the public approved them.

Irish Home Rule

The elections in 1910 meant the Liberal government relied on the Irish Nationalists to stay in power. This forced them to consider Home Rule for Ireland. With the Parliament Act 1911 passed, which limited the House of Lords' power to delay bills, the Conservatives knew that a Home Rule Bill would likely become law by 1914.

Bonar Law, whose family had ties to Ulster (a region in Northern Ireland), believed that the differences between Ulster Unionists (who wanted to stay part of the UK) and Irish Nationalists (who wanted self-rule) were too great. He called the Parliament Act an attempt to bring Home Rule "through the back door."

As leader, he used his position to speak out against Home Rule. He argued that if the Liberals wanted to pass a Home Rule Bill, they should hold a general election first. Unlike previous leaders, Bonar Law took a very strong stance against Home Rule, even suggesting he would support resistance to it. He focused on protecting Protestant-majority Ulster from being ruled by a Parliament in Dublin, which would be dominated by Catholics.

Bonar Law was supported by Edward Carson, the leader of the Ulster Unionists. While Bonar Law agreed with their political goals, he did not agree with religious intolerance. The debate over Home Rule became very heated. In January 1912, when Winston Churchill planned to speak in Belfast in favor of Home Rule, the Ulster Unionist Council threatened violence to stop him. Churchill eventually canceled his speech.

Third Home Rule Bill

The 1912 Parliament session began with the Liberal Party planning a new Home Rule Bill. Bonar Law visited Ulster before the bill was introduced. At a large meeting in Belfast, both Law and Carson promised the crowd that they would "never under any circumstances submit to Home Rule."

However, the Parliament Act and the government's majority made it hard to stop the bill unless the government fell or an election was called. Another problem was that not all Unionists agreed on how to oppose Home Rule. Some wanted to stop it completely, while others thought it was unavoidable and just wanted the best deal for Ulster. There was also talk of civil war, as Ulstermen began forming groups like the Ulster Volunteers to fight if needed.

Bonar Law and the Unionists had three main complaints about the Home Rule Bill:

- Ulster would not accept forced Home Rule. If the Liberals tried to force it, military action would be needed. Bonar Law questioned if the British Army would fight against "a million Ulstermen marching under the Union Flag."

- The government refused to hold a general election on the issue.

- The Liberals had not yet created a new second chamber for Parliament, as promised in the Parliament Act. The Unionists argued that the Liberals were changing the constitution while it was incomplete.

In July 1912, Asquith, the Prime Minister, visited Dublin and criticized the Unionists. In response, the Unionists held a large meeting at Blenheim Palace. Bonar Law spoke there, saying that if the government tried to force Home Rule, he would support Ulster in "any length of resistance." He warned that the government would be "lighting the fires of civil war." This speech was widely discussed and criticized.

Despite the strong opposition, the Home Rule Bill continued through Parliament. An amendment was proposed to exclude four Ulster counties from the Irish Parliament. This put Bonar Law in a difficult spot. If he accepted it, he might seem to be abandoning other Irish Unionists. But if the amendment passed, it might cause problems for the government. The amendment failed, but it showed divisions within the Liberal government.

The Unionists in Ulster were determined to stay out of any Irish Home Rule. They planned to set up their own temporary government if Home Rule was passed. On September 28, 1912, Carson led over 237,000 people in signing the Ulster Covenant. This document stated that Ulster would refuse to recognize any Irish Parliament. This was seen as a strong statement of resistance.

When Parliament met again, the Home Rule Bill was passed by the Commons but rejected by the House of Lords. Under the Parliament Act, it would need to be passed two more times by the Commons to become law.

Second Passage

The Home Rule Bill was passed again by the Commons on July 7, 1913, and again rejected by the Lords on July 15. In response, the Ulster Unionists formed a paramilitary group, the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), to fight against the British government if needed.

During this time, Bonar Law was under pressure from some Conservatives to find a compromise. He believed that the British public was "sick of the whole Irish question" and would likely agree to a compromise that excluded Ulster from Home Rule.

The Unionists tried to convince the King to intervene. They suggested he should ask for an election or an all-party meeting to resolve the issue. The King agreed and asked Prime Minister Asquith to consider this.

Asquith and Bonar Law met privately several times. Asquith suggested different ways to handle Ulster, such as giving Ulster partial self-rule within Home Rule, or excluding Ulster for a few years, or excluding Ulster for as long as it wanted. Bonar Law made it clear that only the option of Ulster being excluded for as long as it wished might be acceptable. They also discussed which parts of Ulster would be excluded.

However, these talks failed. From January 1914, Bonar Law returned to the position that the Unionists were "utterly opposed to Home Rule." A "British Covenant" was launched, where people pledged to resist the Home Rule Bill if it passed. Hundreds of thousands signed it.

Critics said Bonar Law's actions were unconstitutional and encouraged civil war. His supporters argued he was trying to force the Liberal government to hold an election, which they had been avoiding.

World War I

On July 30, 1914, just before World War I began, Bonar Law met with Prime Minister Asquith. They agreed to temporarily stop arguing about Home Rule to focus on the war. By the next day, both leaders had convinced their parties to agree. On August 3, Bonar Law promised in Parliament that his Conservative Party would give "unhesitating support" to the government's war policy. On August 4, Britain declared war on Germany.

Over the next few months, the political parties agreed to a truce, stopping their political fights during the war. However, the Conservatives soon became frustrated that they couldn't criticize the government. They started attacking individual ministers instead.

By late 1914, Bonar Law and David Lloyd George discussed the idea of a coalition government (a government formed by multiple parties). Bonar Law supported the idea.

Coalition Government

How it Started

A crisis over a shortage of artillery shells for the army, and the resignation of a top naval officer, forced the creation of a coalition government. Prime Minister Asquith had praised his government's efforts, but a newspaper article blamed the lack of shells for a British military failure. This angered Conservative politicians.

Bonar Law managed to calm his party for a short time. But when the naval officer, Lord Fisher, resigned, it became clear that a coalition was needed. Fisher had disagreed with Winston Churchill over a military campaign. Bonar Law met with David Lloyd George, and they agreed that a coalition government was the only way to keep a united front during the war.

Bonar Law helped the Liberal Party form the new government. They wanted to remove Lord Kitchener from the War Office, but public support for him made it impossible. So, a new Ministry of Munitions was created to handle weapons supply, with Lloyd George in charge.

Bonar Law became Secretary of State for the Colonies, a less important role during wartime. Other Conservatives also joined the new government, including Arthur Balfour and Austen Chamberlain.

Colonial Secretary

As Colonial Secretary, Bonar Law dealt with issues like getting enough soldiers for the army, the situation in Ireland, and the Dardanelles Campaign (a military operation). The Dardanelles Campaign was a priority. Bonar Law disagreed with sending more troops there, but he felt he couldn't stop it. The campaign resulted in heavy losses for little gain.

Bonar Law joined the coalition government in May 1915. After Prime Minister Asquith resigned in December 1916, King George V asked Bonar Law to form a government. However, Bonar Law suggested David Lloyd George instead, believing Lloyd George was better suited to lead a wartime coalition.

Bonar Law served in Lloyd George's War Cabinet, first as Chancellor of the Exchequer and then as Leader of the House of Commons. As Chancellor, he raised a tax on cheques. He and Lloyd George worked well together, and their coalition won a large election victory after the war ended. Sadly, both of Bonar Law's eldest sons were killed during the war. In the 1918 election, Bonar Law was elected to Parliament for Glasgow Central.

After the War and Prime Minister

After the war, Bonar Law took on a less demanding role as Lord Privy Seal, but he remained Leader of the Commons. In 1921, his poor health forced him to resign as Conservative leader. Austen Chamberlain took over.

By 1921–22, the coalition government had become unpopular. There were concerns about how it was run. Also, the government's willingness to get involved in other countries' affairs, like Russia, didn't fit with the new desire for peace. Economic problems and strikes also made the government unpopular.

Lloyd George and others wanted to use military force against Turkey (the Chanak Crisis). But they had to back down when only New Zealand and Newfoundland offered support, not Canada, Australia, or South Africa. Bonar Law wrote to The Times newspaper, supporting the government but stating that Britain could not be "the policeman for the world."

At a meeting, Conservative politicians voted to end the coalition with Lloyd George. Stanley Baldwin led this move. Austen Chamberlain resigned as Party Leader, and Lloyd George resigned as Prime Minister. Bonar Law then took both jobs on October 23, 1922.

Many important Conservatives did not join Bonar Law's new Cabinet. Parliament was immediately dissolved, and a General Election was held. The Labour Party became a major national party for the first time. Despite the confusing political situation, the Conservatives won a comfortable majority.

One challenge for Bonar Law's government was war debts. Britain owed money to the United States, and other Allied countries owed Britain even more. Stanley Baldwin, the new Chancellor of the Exchequer, agreed to repay a large amount to the United States. This deal was announced to the press before the Cabinet had fully discussed it. Bonar Law was very upset but was convinced not to resign.

Resignation and Death

Bonar Law was soon diagnosed with terminal throat cancer. He could no longer speak in Parliament and resigned on May 20, 1923. King George V then asked Stanley Baldwin to become Prime Minister. Bonar Law died later that year in London at age 65. His funeral was held at Westminster Abbey, where his ashes were buried.

Bonar Law was the shortest-serving prime minister of the 20th century. He is sometimes called "the unknown prime minister." This name comes from a remark by Asquith at Bonar Law's funeral, comparing him to the Unknown Soldier.

A small village in Canada, Bonarlaw, Ontario, is named after him. The Bonar Law Memorial High School in his birthplace, Rexton, New Brunswick, Canada, is also named in his honor.

Bonar Law's Government, October 1922 – May 1923

- Bonar Law – Prime Minister and Leader of the House of Commons

- Lord Cave – Lord Chancellor

- Lord Salisbury – Lord President of the Council and Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

- Stanley Baldwin – Chancellor of the Exchequer

- William Clive Bridgeman – Secretary of State for the Home Department

- Lord Curzon of Kedleston – Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs and Leader of the House of Lords

- The Duke of Devonshire – Secretary of State for the Colonies

- Lord Derby – Secretary of State for War

- Lord Peel – Secretary of State for India

- Lord Novar – Secretary for Scotland

- Leo Amery – First Lord of the Admiralty

- Sir Philip Lloyd-Greame – President of the Board of Trade

- Sir Robert Sanders – Minister of Agriculture and Fisheries

- Edward Wood – President of the Board of Education

- Sir Montague Barlow – Minister of Labour

- Sir Arthur Griffith-Boscawen – Minister of Health

Changes

- April 1923 – Griffith-Boscawen resigned as Minister of Health after losing his seat and was replaced by Neville Chamberlain.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Andrew Bonar Law para niños

In Spanish: Andrew Bonar Law para niños