Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Earl Kitchener

|

|

|---|---|

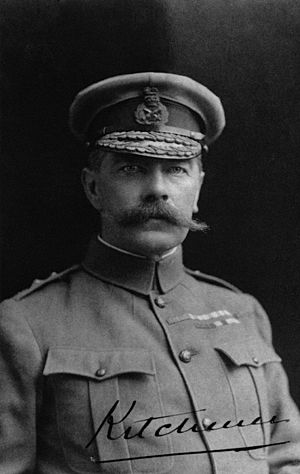

Kitchener in full dress uniform (July 1910)

|

|

| Secretary of State for War | |

| In office 5 August 1914 – 5 June 1916 |

|

| Monarch | George V |

| Prime Minister | H. H. Asquith |

| Preceded by | H. H. Asquith |

| Succeeded by | David Lloyd George |

| Consul-General in Egypt | |

| In office 1911–1914 |

|

| Member of the House of Lords Lord Temporal |

|

| In office 1 November 1898 – 5 June 1916 Hereditary peerage |

|

| Preceded by | Peerage created |

| Succeeded by | The 2nd Earl Kitchener |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 24 June 1850 Ballylongford, County Kerry, Ireland |

| Died | 5 June 1916 (aged 65) HMS Hampshire, west of Orkney, Scotland |

| Cause of death | Killed in action (drowning) |

| Relations | The 2nd Earl Kitchener (brother) Sir Walter Kitchener (brother) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Branch/service | British Army |

| Years of service | 1871–1916 |

| Rank | Field marshal |

| Commands | Commander-in-Chief, India (1902–1909) British Forces in South Africa (1900–1902) Egyptian Army (1892–1899) |

| Battles/wars | Franco-Prussian War Mahdist War Second Boer War First World War |

| Awards | Complete list |

Field Marshal Horatio Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener, (24 June 1850 – 5 June 1916) was a very important British Army officer and a colonial administrator. He became famous for his military campaigns in different parts of the British Empire. He played a big role in the Second Boer War and was central to the early part of the First World War.

In 1898, Kitchener was praised for winning the Battle of Omdurman. This victory helped Britain control the Sudan. After this, he was given the title of Baron Kitchener. During the Second Boer War (1900–1902), he was Chief of Staff. He helped in the British takeover of the Boer Republics. Later, he became the commander-in-chief. At this time, Boer forces fought using guerrilla tactics.

From 1902 to 1909, Kitchener was the Commander-in-Chief of the Army in India. He had disagreements with Lord Curzon, who was the Viceroy. Curzon eventually resigned. After India, Kitchener returned to Egypt as a British representative.

In 1914, when the First World War began, Kitchener became the Secretary of State for War. This was a very important government job. He was one of the few people who believed the war would last a long time, maybe three years or more. He organized the largest volunteer army Britain had ever seen. He also made sure Britain produced many more weapons and supplies for the war on the Western Front. Even though he warned about the difficulties of supplying a long war, he was blamed for a shortage of shells in 1915. This led to him losing some control over military supplies and strategy.

On 5 June 1916, Kitchener was traveling to Russia on HMS Hampshire. He was going to meet with Tsar Nicholas II for talks. In bad weather, his ship hit a German mine about 1.5 miles (2.4 km) west of Orkney, Scotland, and sank. Kitchener was one of 737 people who died. He was the highest-ranking British officer to die in action during the entire war.

Contents

Early Life and Military Beginnings

Horatio Herbert Kitchener was born on 24 June 1850. His birthplace was Ballylongford in County Kerry, Ireland. His father, Henry Horatio Kitchener, was an army officer. His mother was Frances Anne Chevallier.

Both sides of Kitchener's family came from Suffolk, England. His mother's family had French roots. His father had recently bought land in Ireland. Later, his family moved to Switzerland. Young Kitchener went to school in Montreux. Then he studied at the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich in England.

Joining the French Army

During the Franco-Prussian War, Kitchener wanted to see action. He joined a French field ambulance unit. His father brought him back to Britain. This was after Kitchener got sick while trying to see the French army from a balloon.

He officially joined the Royal Engineers on 4 January 1871. His service with the French army had gone against British neutrality. He was told off by the Duke of Cambridge, who was the commander-in-chief. After this, he worked as a surveyor in Palestine, Egypt, and Cyprus. He learned to speak Arabic. He also made detailed maps of these areas.

Mapping the Holy Land

In 1874, when Kitchener was 24, he was asked to help map the Holy Land. This was for the Palestine Exploration Fund. He took over from another officer who had died. Kitchener joined fellow officer Claude R. Conder.

From 1874 to 1877, they surveyed Palestine. They only returned to England briefly in 1875. This was after an attack by local people in Safed, Galilee.

The Survey's Impact

Conder and Kitchener's work became known as the Survey of Western Palestine. It mainly covered the area west of the Jordan River. They collected information about the land and place names. They also noted local plants and animals.

The results of their survey were published in eight books. Kitchener wrote parts of the first three books. This survey had a lasting impact on the Middle East.

- It created the basis for the grid system used in modern maps of Israel and Palestine.

- The information they gathered is still used by experts today.

- The survey helped define the borders of the southern Levant. For example, the modern border between Israel and Lebanon is where their survey stopped.

In 1878, after finishing the Palestine survey, Kitchener went to Cyprus. He surveyed this new British area. In 1879, he became a vice-consul in Anatolia.

Service in Egypt

On 4 January 1883, Kitchener was promoted to captain. He was also given the Turkish rank of binbasi (major). He was sent to Egypt to help rebuild the Egyptian Army.

Egypt had become a British protectorate. Its army was led by British officers. Kitchener became second-in-command of an Egyptian cavalry group in February 1883. He then took part in an attempt to rescue Charles George Gordon in the Sudan in late 1884. This rescue mission was not successful.

Kitchener's Personality and Skills

Kitchener spoke Arabic very well. He preferred the company of Egyptians over other British people. He once wrote in 1884 that he was "happier alone." He could even speak the different dialects of the Bedouin tribes.

He was promoted several times. In September 1886, he became Governor of the Egyptian Provinces of Eastern Sudan. He also became a Pasha that year. In January 1888, he led his forces against the followers of the Mahdi at Handub. He was injured in the jaw during this fight.

Kitchener was promoted to colonel in April 1888. He became a major in July 1889. He led the Egyptian cavalry at the Battle of Toski in August 1889. In 1890, he became Inspector General of the Egyptian police. Later that year, he became Adjutant-General of the Egyptian Army. In April 1892, he became Sirdar (Commander-in-Chief) of the Egyptian Army.

Kitchener was tall, about 6 feet 2 inches (1.88 m). He seemed to tower over most people. His appearance added to his mysterious image. Sir Evelyn Baring, the British ruler of Egypt, thought Kitchener was "the most able (soldier) I have come across."

Conquering Sudan and Khartoum

In 1896, the British Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury, wanted to stop France from taking control of the Horn of Africa. A French group was trying to conquer the Sudan. Salisbury feared that if Britain did not act, France would control the Nile.

Salisbury ordered Kitchener to invade northern Sudan. The official reason was to distract the Ansar (whom the British called "Dervishes") from attacking the Italians.

Key Victories and Building a Railway

Kitchener won battles at Battle of Ferkeh in June 1896 and the Battle of Hafir in September 1896. These victories made him famous in the United Kingdom. He was promoted to major-general in September 1896. Kitchener was known for being tough on his men.

He had been part of an earlier expedition to rescue General Gordon in Khartoum. Kitchener believed that expedition failed because supplies were brought by boats. He wanted to build a railway to supply the Anglo-Egyptian army. He put Percy Girouard, a Canadian, in charge of building the Sudan Military Railroad.

Kitchener had more successes at the Battle of Atbara in April 1898. Then came the Battle of Omdurman in September 1898. He arranged his army in a crescent shape with the Nile behind them. This allowed them to use their strong firepower against any attack.

On 2 September 1898, a large force of Ansar attacked. Kitchener's army opened fire with artillery, then machine guns, and finally rifles. A young Winston Churchill, who was an officer there, described the fierce fighting. By 8:30 am, many of the Dervish army were dead. Kitchener ordered his men to advance.

After Omdurman

After the battle, Kitchener rode into Omdurman. He immediately ordered that thousands of Christians enslaved by the Ansar were now free. Kitchener lost fewer than 500 men. About 11,000 of the Ansar were killed and 17,000 wounded. Kitchener ordered the Mahdi's tomb to be blown up. He did this to stop it from becoming a rallying point for his followers.

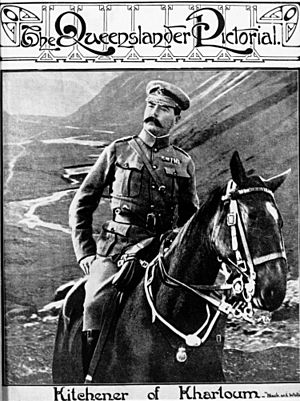

The victory at Omdurman made Kitchener a popular war hero. He gained a reputation for being very efficient. He was given the title Baron Kitchener, of Khartoum and of Aspall.

The Fashoda Incident

After Omdurman, Kitchener received a secret letter. It said the real reason for conquering Sudan was to stop France. Salisbury ordered Kitchener to go south to remove a French group led by Jean-Baptiste Marchand.

On 18 September 1898, Kitchener reached the French fort at Fashoda. He told Marchand to leave Sudan, but Marchand refused. This led to a tense situation known as the Fashoda Incident. British and French soldiers aimed their weapons at each other. Britain and France almost went to war.

Kitchener spoke French fluently. He was diplomatic in his talks with Marchand. They agreed that both flags would fly over the fort. In November 1898, the crisis ended. France agreed to leave Sudan.

Kitchener became Governor-General of the Sudan in September 1898. He worked to restore good government. He focused on education, building Gordon Memorial College. He rebuilt mosques and made Friday the official day of rest. He also protected religious freedom for all citizens.

The Anglo-Boer War

During the Second Boer War, Kitchener arrived in South Africa in December 1899. He came with Lord Roberts and many British soldiers. Kitchener was Roberts' second-in-command. He was present at the relief of Kimberley. He also led an attack at the Battle of Paardeberg in February 1900, which was not successful.

Taking Command and Difficult Tactics

Kitchener took over as overall commander in November 1900. He was promoted to lieutenant-general and then to general. He continued and expanded strategies to make the Boer fighters surrender. These included using concentration camps and burning farms.

Conditions in the concentration camps became very bad. Many Boer civilians, especially women and children, were held there. The camps lacked space, food, and medicine. This led to many deaths from disease. About 26,370 women and children died in these camps. Emily Hobhouse, a British humanitarian, criticized the camps. She published a report about the terrible conditions.

Historians have described Kitchener's war actions as a "scorched earth policy." This means his forces destroyed homes, poisoned wells, and targeted women and children.

Ending the War

The Treaty of Vereeniging, which ended the war, was signed in May 1902. Kitchener wanted a peace treaty that would be fair to the Afrikaners (Boers). He wanted them to have some rights and future self-government. However, Sir Alfred Milner and the British government wanted a harsher peace.

Kitchener was promoted to the full rank of general on 1 June 1902. He left South Africa in July 1902. He received a very warm welcome when he arrived in the United Kingdom. He was given the title Viscount Kitchener.

Service in India

In late 1902, Kitchener was appointed Commander-in-Chief, India. He arrived in November and immediately began to reorganize the Indian Army. His plan was to prepare the army for any potential war. He wanted to reduce fixed garrisons and organize the army into two main forces.

Kitchener's reforms were supported by the Viceroy, Lord Curzon. However, the two men eventually disagreed. They clashed over how the military should be managed. Kitchener wanted more control over military decisions. He won the support of the government in London. Lord Curzon chose to resign because of this disagreement.

Later Years in India

Kitchener oversaw the Rawalpindi Parade in 1905. This was to honor the Prince and Princess of Wales's visit to India. That same year, Kitchener founded the Indian Staff College at Quetta. His time as Commander-in-Chief in India was extended by two years in 1907.

Kitchener was promoted to the highest Army rank, Field Marshal, on 10 September 1909. He then toured Australia and New Zealand. He hoped to become the Viceroy of India, but this did not happen. The Prime Minister, H. H. Asquith, was sympathetic but would not go against the Secretary of State for India. So, Kitchener was not given the Viceroy position in 1911.

From 22 to 24 June 1911, Kitchener took part in the Coronation of King George V and Mary. He was in charge of the escort, protecting the royals. He also commanded 55,000 British and imperial soldiers in London. During the ceremony, he held one of the four swords guarding the monarch. In November 1911, Kitchener hosted the King and Queen in Port Said, Egypt.

Return to Egypt and World War I

In June 1911, Kitchener returned to Egypt. He served as the British Agent and Consul-General. This meant he was the de facto administrator of Egypt.

He was given the title Earl Kitchener, of Khartoum and of Broome, on 29 June 1914. During this time, he became a supporter of Scouting. He famously said, "once a Scout, always a Scout."

Becoming Secretary of State for War

When the First World War started, Prime Minister Asquith quickly made Kitchener the Secretary of State for War. Kitchener was in Britain on leave and was about to return to Cairo when he was called back to London. War was declared the next day.

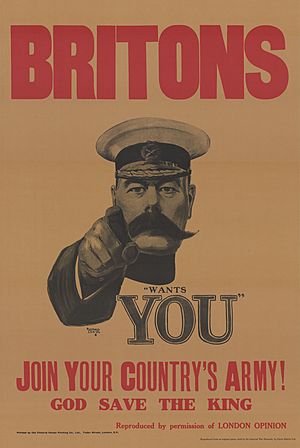

Against the opinion of others, Kitchener correctly predicted a long war. He believed it would last at least three years. He also knew it would need huge new armies to defeat Germany. He said the conflict would use up manpower "to the last million." A massive recruitment campaign began. It featured a famous poster of Kitchener, saying "Your country needs you!" This image became one of the most lasting symbols of the war.

Kitchener built the "New Armies" as separate units. He did this because he did not trust the existing Territorials.

Deploying British Forces

At the War Council on 5 August 1914, Kitchener argued that the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) should be placed at Amiens. He thought it could launch a strong counterattack there. Kitchener believed that deploying the BEF in Belgium would lead to a quick retreat. He was proven right.

Kitchener decided that the first BEF would have only 4 infantry divisions. This was fewer than promised. He wanted to save resources for a long war. This decision may have saved the BEF from disaster.

Kitchener gave orders to the BEF commander, Sir John French. He told French to work with the French army but not to take direct orders from them. Kitchener also told French to avoid too many losses. This was because the BEF was Britain's only field army.

Meeting with Sir John French

Sir John French, the BEF commander, thought about pulling his forces back. This was after heavy British losses at the Battle of Le Cateau. French leaders and Kitchener urged him not to. Kitchener went to France to meet with Sir John on 1 September.

They met with the French Prime Minister and War Minister. Kitchener was described as "calm, balanced, reflective." Sir John was "sour, impetuous." After their private meeting, Kitchener told the Cabinet that the BEF would stay in the line. He told French this was an "instruction."

French was upset that Kitchener wore his field marshal's uniform. French felt Kitchener was acting as his military superior, not just a government official. By the end of the year, French thought Kitchener had "gone mad."

World War I: Strategy and Challenges

In January 1915, Field Marshal Sir John French wanted the New Armies to join existing divisions. He thought the war would end soon. But Kitchener disagreed. He refused to be overruled by the Prime Minister. This made relations between French and Kitchener worse.

Kitchener warned that the Western Front was like a siege line. It would be hard to break through. He tried to find ways to relieve pressure on the Western Front. He suggested an invasion of Alexandretta in the Ottoman Empire. This area was important for railways. However, he was persuaded to support Winston Churchill's difficult Gallipoli Campaign in 1915–1916.

The failure of the Gallipoli Campaign and the Shell Crisis of 1915 hurt Kitchener's reputation. The public still liked him, so Asquith kept him in the government. But a new ministry, led by David Lloyd George, took over responsibility for munitions. Kitchener was also doubtful about the tank. So, its development was handled by the Admiralty.

Changing Plans and Reduced Powers

With Russian forces retreating, Kitchener thought Germany might send more troops west. He also worried about a possible invasion of Britain. He told the War Council in May 1915 that he would not send the New Armies overseas. He wanted to save them for a big attack in 1916–17. However, by summer 1915, he realized that heavy casualties and a major commitment to France were unavoidable.

At a meeting in Calais in July, Kitchener agreed to send New Army divisions to France. An Allied conference in Chantilly agreed on coordinated attacks. Kitchener then supported the upcoming Loos offensive. New Army divisions first fought at Loos in September 1915.

Kitchener continued to lose favor with politicians and soldiers. He found it hard to discuss military secrets with many people he barely knew. He was blamed for opposing conscription (which was later introduced). He was also blamed for civilians having too much influence over strategy.

In January 1916, an agreement was made. Sir William Robertson would give strategic advice to the Cabinet. Kitchener would be responsible for recruiting and supplying the Army. They would both sign military orders.

1916: Final Months

Early in 1916, Kitchener visited Douglas Haig, the new Commander-in-Chief of the BEF in France. Kitchener had helped remove Haig's predecessor, Sir John French. Haig valued Kitchener's military opinion against civilian "folly." However, Haig thought Kitchener looked "pinched, tired, and much aged."

Kitchener was pressured by the French Prime Minister to attack on the Western Front. This was to help relieve pressure from the German attack at Verdun.

On 2 June 1916, Kitchener answered questions from politicians. He explained why only a small number of rifles and shells had arrived from US manufacturers. He received a strong vote of thanks from the Members of Parliament. They thanked him for his honesty and efforts to arm the troops.

Kitchener's Death

Mission to Russia

Kitchener had been paying close attention to the difficult situation on the Eastern Front. He helped provide war materials to the Russian armies. In May 1916, the Chancellor of the Exchequer suggested Kitchener lead a secret mission to Russia. He was to discuss supply shortages, military strategy, and money problems with the Russian government and military leaders. Both Kitchener and the Russians wanted face-to-face talks. The Tsar sent a formal invitation on 14 May.

Kitchener left London by train for Scotland on the evening of 4 June. He traveled with officials, military aides, and personal servants.

Lost at Sea

Kitchener sailed from Scrabster to Scapa Flow on 5 June 1916. He had lunch with Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, commander of the Grand Fleet. Kitchener was eager to discuss the recent Battle of Jutland. He also looked forward to his three-week diplomatic mission to Russia.

He then set out for Russia on board the armoured cruiser HMS Hampshire. Admiral Jellicoe changed Hampshire's route at the last minute. This was based on a misunderstanding of the weather forecast. It also ignored recent reports of German U-boat activity.

Shortly before 7:30 pm that same day, Hampshire hit a mine. The mine was laid by the German U-boat U-75. The ship sank west of the Orkney Islands during a strong gale. About 737 people died on board Hampshire. Only twelve men survived. All ten members of Kitchener's group died. Kitchener himself was seen standing on the ship's deck as it sank. His body was never found.

The news of Kitchener's death shocked the entire British Empire. People were very upset. King George V wrote in his diary that it was a "heavy blow" and a "great loss." He ordered army officers to wear black armbands for a week.

Kitchener's Legacy

Kitchener is officially remembered in a chapel at St Paul's Cathedral in London. A memorial service was held there in his honor.

In Canada, the city of Berlin, Ontario, was renamed Kitchener in 1916. This was done to honor him.

Since 1970, new historical records have been opened. These have helped improve Kitchener's reputation. Some historians now praise his strategic vision in the First World War. They highlight his work in expanding munitions production. They also note his key role in raising the British army in 1914 and 1915. This provided a force ready to fight in Europe.

His powerful image on recruiting posters, saying "Your country needs you!", is still famous today. It has been copied and parodied many times.

Memorials

- As a British soldier lost at sea in World War I, Kitchener is remembered on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission's Hollybrook Memorial. This is at Hollybrook Cemetery in Southampton, Hampshire.

- Blue plaques mark where Kitchener lived in Carlton Gardens, Westminster, and at Broome Park near Canterbury.

- The northwest chapel of All Souls at St Paul's Cathedral, London, was rededicated as the Kitchener Memorial in 1925.

- A month after his death, the Lord Kitchener National Memorial Fund was set up. It helped war casualties. After the war, it helped soldiers and their children get university educations.

- The Lord Kitchener Memorial Homes in Chatham, Kent, provide affordable housing for servicemen and women.

- A statue of Kitchener on a horse is on Khartoum Road in Chatham, Kent.

- The Kitchener Memorial on Mainland, Orkney, is a stone tower. It is on the cliff edge at Marwick Head, near where he died.

- In the early 1920s, a road in Dudley, West Midlands, was named Kitchener Road in his honor.

- The east window of the chancel at St George's Church, Eastergate, West Sussex, has stained glass remembering Kitchener.

- In December 2013, the Royal Mint announced plans for commemorative two-pound coins in 2014. They featured Kitchener's "Call to Arms."

- A memorial cross for Kitchener was unveiled at St Botolph-without-Bishopsgate church in 1916.

- One of the three houses of the Rashtriya Indian Military College, India, was named after Kitchener.

- A memorial tree was dedicated to Kitchener a month after his death in Eurack, Victoria.

Honours and Decorations

Kitchener received many awards and honors from the British government. He also received medals from allied nations. His other decorations included: British

- Knight of the Order of the Garter (KG) – 3 June 1915

- Knight of the Order of St Patrick (KP) – 19 June 1911

- Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath (GCB) – 15 November 1898

- Member of the Order of Merit (OM) – 12 July 1902

- Knight Grand Commander of the Order of the Star of India (GCSI) – 25 June 1909

- Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George (GCMG) – 29 November 1900

- Knight Grand Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire (GCIE) – 1 January 1908

Foreign

- Order of Osmanieh (Ottoman Empire) first class – 7 December 1896

- Order of the Medjidie (Ottoman Empire) first class – 18 November 1893

- Order of Karađorđe's Star with swords, Kingdom of Serbia – 1918

Honorary Regimental Appointments

- Honorary Colonel, Scottish Command Telegraph Companies (Army Troops, Royal Engineers) – 1898

- Honorary Colonel, East Anglian Divisional Engineers, Royal Engineers – 1901

- Honorary Colonel, 5th (7th Royal Lancashire Militia) Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers – 11 June 1902

- Honorary Colonel, 4th, later 6th Battalion, Royal Scots – 1905

- Colonel Commandant, Royal Engineers – 1906

- Honorary Colonel, 7th Gurkha Rifles – 1908

- Honorary Colonel, 1st County of London Yeomanry – 1910

- Colonel-in-Chief, Corps of New Zealand Engineers – 1911

- Regimental Colonel, Irish Guards – 1914

Honorary Degrees and Offices

- Freedom of the borough, Southampton, 12 July 1902

- Freedom of the borough, Ipswich, 22 September 1902

- Freedom of the city, Sheffield, 30 September 1902.

- Freedom of the borough, Chatham, 4 October 1902

- Honorary Freedom of the City of Liverpool, 11 October 1902

- Honorary Freeman of the Worshipful Company of Fishmongers

- Honorary Freeman of the Worshipful Company of Grocers, 1 August 1902.

See also

In Spanish: Herbert Kitchener para niños

In Spanish: Herbert Kitchener para niños

- Anglo-Egyptian conquest of Sudan – a reconquest of territory lost by the Khedives of Egypt in 1884 and 1885 during the Mahdist War

- Kitchener's Army – an all-volunteer army formed in the United Kingdom from 1914

- Kitchener, Ontario – Canadian city renamed from Berlin after Kitchener's death

- Statue of the Earl Kitchener, London

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |