Mahdist War facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Mahdist War |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

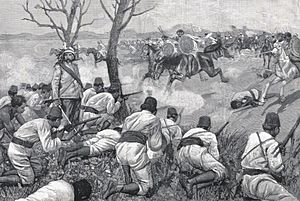

Depiction of the Battle of Omdurman |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

* |

|||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

The Mahdist War (Arabic: الثورة المهدية, romanized: ath-Thawra al-Mahdiyya) was a big conflict that happened between 1881 and 1899. It was fought between the Mahdist Sudanese people and the forces of Egypt, and later Britain.

The war was led by a religious leader named Muhammad Ahmad, who said he was the "Mahdi" (the "Guided One") of Islam. After 18 years of fighting, Britain and Egypt took control of Sudan together. This was called the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan (1899–1956). Even though it was supposed to be joint rule, Britain mostly controlled Sudan.

The Sudanese also tried to invade nearby countries. This made the war bigger, involving not only Britain and Egypt, but also Italy, the Congo Free State, and the Ethiopian Empire. The part of the war involving Britain is often called the Sudan campaign. Other names for this war include the Mahdist Revolt or the Anglo–Sudan War.

Contents

Why the War Started

After Muhammad Ali invaded in 1819, Sudan was ruled by Egypt. The Sudanese people did not like this rule. They especially disliked the high taxes and the harsh way Egypt started its control.

Many Sudanese people faced hard times because of these taxes. Farmers and small traders had to pay a fixed tax. This tax was collected by tax collectors from the Sha'iqiyya tribe. During bad years, like droughts, farmers could not pay. Many farmers left their villages near the Nile Valley. They moved to faraway areas like Kordofan and Darfur. These people became small traders.

By the mid-1800s, Egypt was deeply in debt. This was because of the spending of its ruler, Khedive Ismail. When his plans for the Suez Canal ran into trouble, Britain helped pay his debts. In return, Britain gained control of parts of the canal. The Suez Canal was very important for Britain. It was the fastest way to India.

Because of Egypt's debt and problems, Britain became more involved. In 1873, Britain helped set up a group to manage Egypt's money. This group eventually made Khedive Ismail step down in 1879. His son, Tawfiq, took over. This caused political unrest.

Also in 1873, Ismail had appointed General Charles "Chinese" Gordon to govern parts of Sudan. Gordon fought against a local leader in Darfur for three years. When Ismail stepped down, Gordon lost support. He resigned in 1880. His policies were soon changed, and the anger of the local people grew. Even though Egypt was worried, Britain did not want to get involved in Sudan at first.

How the Conflict Developed

The Mahdi's Uprising

Many things led to the uprising. Sudanese people were angry at their foreign Egyptian rulers. Some Muslims were upset that Egypt's religious rules were not strict enough. They also disliked that non-Muslims, like Charles Gordon, held high positions. Another reason for anger was Egypt stopping the trade of enslaved people. This trade was a major source of income in Sudan.

In the 1870s, a Muslim religious leader named Muhammad Ahmad began to preach. He called for a renewal of faith and freedom for the land. He soon gained many followers. He openly rebelled against the Egyptians. Muhammad Ahmad declared himself the Mahdi, the promised savior of the Islamic world.

In August 1881, the governor of Sudan, Raouf Pasha, sent soldiers to arrest him. Two companies of infantry, each with a machine gun, were sent. They approached the Mahdi's village on Aba Island from different directions. They arrived at the same time and accidentally fired at each other. This allowed the Mahdi's few followers to attack and defeat both groups at the Battle of Aba.

The Mahdi then moved to Kordofan. This put him far from the government in Khartoum. This move was seen as a great success. It encouraged many Arab tribes to join the Jihad (holy war) the Mahdi had declared against the Egyptian rulers.

In November 1881, the Mahdi and his followers, called the Ansar, arrived in the Nuba Mountains. Another Egyptian group was sent from Fashoda a month later. This group was ambushed and destroyed on December 9, 1881. The commander and all his main leaders died.

The Mahdi made his movement stronger by comparing it to the life of the Prophet Muhammad. He called his followers Ansar, like those who welcomed the Prophet in Medina. He called his move away from the British the hijrah, like the Prophet's flight. He also chose commanders to represent important early Islamic leaders. For example, he said Abdallahi ibn Muhammad, who would later take over, represented Abu Bakr, the Prophet's successor.

The Egyptian government in Sudan was very worried. They gathered 4,000 troops under Yusef Pasha. In mid-1882, this force approached the Mahdist group. The Mahdists were poorly dressed and armed only with sticks and stones. But the Egyptian army was too confident. They camped near the Mahdist 'army' without guards. The Mahdi led a surprise attack at dawn on June 7, 1882. The Egyptian army was completely defeated. The rebels gained many weapons, ammunition, and supplies.

Hicks' Expedition

As the Egyptian government came under British control, European countries noticed the problems in Sudan. British advisors in Egypt agreed to another military trip. In the summer of 1883, Egyptian troops gathered in Khartoum. They had about 7,300 infantry (foot soldiers), 1,000 cavalry (horse soldiers), and 300 artillery (big guns) personnel.

This force was led by William Hicks, a retired British officer, and twelve European officers. Winston Churchill later called this army "perhaps the worst army that has ever marched to war." The soldiers were unpaid, untrained, and undisciplined.

The city of El Obeid, which Hicks wanted to help, had already fallen. But Hicks continued his march. The Mahdi gathered an army of about 40,000 men. He trained them well and gave them weapons captured from earlier battles. On November 3 and 4, 1883, Hicks' forces fought the Mahdist army. The Mahdists completely defeated Hicks' army at the Battle of El Obeid. Only about 500 Egyptians survived.

Egyptians Leave Sudan

At this time, the British Empire was getting more involved in Egypt's government. Egypt owed a huge amount of money to European countries. To avoid more problems, Egypt had to pay its debts on time. So, the British put Egypt's money matters almost entirely under the control of a British financial advisor. This advisor had the power to stop any financial decision.

The British advisors wanted Egypt to spend as little money as possible. Keeping soldiers in Sudan cost Egypt over 100,000 Egyptian pounds a year. This was too expensive. So, the Egyptian government decided to pull its soldiers out of Sudan. They would leave the country to govern itself, probably under the Mahdi.

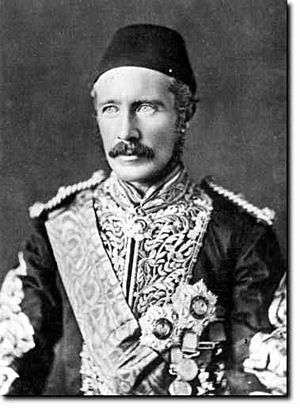

Egypt asked for a British officer to help with this withdrawal. They hoped that the Mahdist forces would not attack a British person, allowing the soldiers to leave safely. Charles 'Chinese' Gordon was chosen. Gordon was a skilled officer. He was famous for leading Chinese forces during the Taiping Rebellion. But he was also known for being aggressive and very honorable. Some British officials thought he was not right for the job.

Sir Evelyn Baring, the British Consul-general in Egypt, was against Gordon's appointment. But the British newspapers and public wanted Gordon. So, Gordon was given the mission. He was joined by Colonel John Donald Hamill Stewart, who was supposed to keep Gordon calm and ensure a quick, peaceful exit from Sudan.

Gordon left England on January 18, 1884. He arrived in Cairo on January 24. Gordon helped write his own orders. These orders clearly stated Egypt's plan to leave Sudan.

Gordon arrived in Khartoum on February 18. He quickly realized how difficult the task was. Egypt's soldiers were spread out across the country. Three garrisons (military posts) were under attack. Most of the land between them was controlled by the Mahdi. There was no guarantee that the soldiers could leave safely without being attacked.

Khartoum had many Egyptians and Europeans, including 7,000 Egyptian soldiers and 27,000 civilians. Gordon felt it would be dishonorable to leave any Egyptian soldiers behind. He also worried that the Mahdi could cause trouble in Egypt if he controlled Sudan. So, Gordon believed the Mahdi had to be "crushed," even if it meant using British troops. It is still debated if Gordon stayed in Khartoum on purpose, wanting to be surrounded.

In March 1884, the Sudanese tribes north of Khartoum joined the Mahdi. These tribes had been friendly or neutral before. On March 15, the telegraph lines between Khartoum and Cairo were cut. Khartoum was now cut off from the outside world.

Siege of Khartoum

Gordon's position in Khartoum was strong. The city was surrounded by the Blue Nile and White Nile rivers. To the south were old forts facing a large desert. Gordon had enough food for about six months. He had millions of rounds of ammunition and could make more. He also had 7,000 Egyptian soldiers.

But outside the walls, the Mahdi had gathered about 50,000 Dervish soldiers. As time passed, it became harder for Gordon to break out. Gordon wanted to bring back a former trader, Pasha Zobeir, from exile. He hoped Zobeir could lead an uprising against the Mahdi. The British government said no to this idea. Gordon then suggested other ways to save his situation. All his ideas were rejected. Some of his ideas included:

- Breaking out south along the Blue Nile towards Ethiopia. This would let him gather other soldiers along the way.

- Asking for Muslim soldiers from India.

- Asking for thousands of Turkish troops to stop the uprising.

- Visiting the Mahdi himself to find a solution.

Eventually, it became clear that Gordon could only be saved by British troops. A relief expedition was sent under Sir Garnet Wolseley. But as the White Nile's water level dropped in winter, muddy areas appeared at the base of the city walls. With hunger and disease spreading in the city, and the Egyptian soldiers losing hope, Gordon's position became impossible. The city fell on January 26, 1885, after being under siege for 313 days.

Nile Campaign

The British Government sent a relief force under Sir Garnet Wolseley. This was done reluctantly and late, but under strong public pressure. This was called the 'Gordon Relief Expedition' by some newspapers. Gordon did not like this name. After beating the Mahdists at the Battle of Abu Klea on January 17, 1885, the force reached Khartoum. But they were too late. The city had fallen two days earlier. Gordon and his soldiers had been killed.

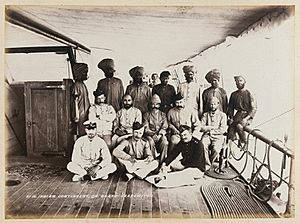

Suakin Expedition

The British also sent soldiers to Suakin in March 1885. This force included soldiers from India. They won two battles but did not change the overall war situation. The force was then pulled out. These events temporarily ended British and Egyptian involvement in Sudan. Sudan then came completely under the control of the Mahdists.

Muhammad Ahmad died soon after his victory, on June 22, 1885. He was replaced by the Khalifa Abdallahi ibn Muhammad. Abdallahi was a strong, but harsh, ruler of the Mahdist state.

Ethiopian Campaigns

In a treaty on June 3, 1884, Ethiopia agreed to help Egyptian soldiers leave southern Sudan. In September 1884, Ethiopia took back the province of Bogos, which Egypt had held. Ethiopia then began a long fight to help the Egyptian soldiers trapped by the Mahdists. Emperor Yohannes IV and Ras Alula led these tough campaigns. The Ethiopians won a victory at the Battle of Kufit on September 23, 1885.

Between November 1885 and February 1886, Yohannes IV was stopping a revolt in Wollo. In January 1886, a Mahdist army invaded Ethiopia. They took Dembea, burned a monastery, and moved towards Chilga. King Tekle Haymanot of Gojjam led a successful counter-attack into Sudan in January 1887. A year later, in January 1888, the Mahdists returned. They defeated Tekle Haymanot and looted Gondar. This part of the war ended at the Battle of Gallabat.

Italian Campaign and British-Egyptian Reconquest

Over the next few years, Egypt still claimed Sudan. The British leaders saw these claims as right. With strict British control, Egypt's economy got better. The Egyptian army was also reformed. It was now trained and led by British officers. This made it possible for Egypt, both politically and militarily, to take back Sudan.

Since 1890, Italian troops had defeated Mahdist forces in battles like Battle of Serobeti and the First Battle of Agordat. In December 1893, Italian colonial troops and Mahdists fought again at the Second Battle of Agordat. The Italians won again. This was seen as the first big victory by Europeans against the Sudanese rebels. A year later, Italian colonial forces took Kassala after the Battle of Kassala.

In 1891, a Catholic priest, Father Joseph Ohrwalder, escaped from being held captive in Sudan. In 1895, Rudolf Carl von Slatin, a former governor of Darfur, also escaped from the Khalifa's prison. Both men gave important information about the Mahdists. They also wrote detailed stories about their time in Sudan. These stories, written with Reginald Wingate, who wanted to reconquer Sudan, showed the Mahdists as savage. This helped turn public opinion in Britain in favor of military action.

In 1896, Italy suffered a big defeat by the Ethiopians at Adwa. This weakened Italy's position in East Africa. The Mahdists then threatened to take back Kassala, which they had lost to the Italians in 1894. The British government decided to help Italy by showing military strength in northern Sudan. This also matched the growing threat of French expansion in the Upper Nile areas. Lord Cromer, thinking the government would want to attack, turned this show of force into a full invasion. In 1897, the Italians gave Kassala back to the British.

Herbert Kitchener, the new commander of the British-Egyptian Army, received his orders on March 12. His forces entered Sudan on March 18. Kitchener's force started with 11,000 men. They had the most modern weapons, including Maxim machine-guns and modern artillery. They were also supported by gunboats on the Nile.

Their advance was slow and careful. They built fortified camps along the way. Two separate narrow-gauge railways were quickly built from Wadi Halfa. The first rebuilt an old line to supply the 1896 Dongola Expedition. The second, built in 1897, went straight across the desert to Abu Hamad. They captured Abu Hamad in the Battle of Abu Hamed on August 7, 1897. This railway helped supply the main force moving towards Khartoum. The first major battle of the campaign happened on June 7, 1896. Kitchener led 9,000 men who wiped out the Mahdist soldiers at Ferkeh.

In 1898, Britain decided to take back Sudan for Egypt. An expedition led by Kitchener was organized in Egypt. It had 8,200 British soldiers and 17,600 Egyptian and Sudanese soldiers. These soldiers were led by British officers. The Mahdist forces, also called Dervishes, had more than 60,000 warriors. But they did not have modern weapons.

After defeating a Mahdist force in the Battle of Atbara in April 1898, the British-Egyptians reached Omdurman, the Mahdist capital, in September. Most of the Mahdist army attacked. But they were cut down by British machine-guns and rifle fire.

The remaining Mahdist soldiers, with the Khalifa Abdullah, ran away to southern Sudan. During the chase, Kitchener's forces met a French force at Fashoda. This led to the Fashoda Incident, a diplomatic crisis. They finally caught Abdullah at Umm Diwaykarat, where he was killed. This effectively ended the Mahdist rule.

The losses for this campaign were:

- Sudan: 30,000 dead, wounded, or captured.

- Britain: Over 700 British, Egyptian, and Sudanese dead, wounded, or captured.

What Happened Next

The British set up a new system called the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan. This gave Britain control over Sudan. This control ended when Sudan became independent in 1956.

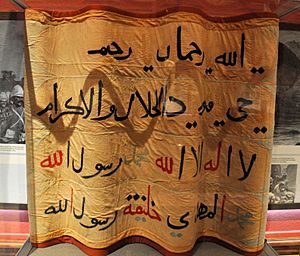

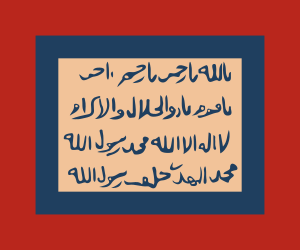

Military Textiles of the Mahdiyya

Clothes and fabrics were very important for the Mahdist forces. The flags, banners, and patched tunics (called jibba) worn by the anṣār had both military and religious meaning. Many of these items were taken back to Britain after the British won the Battle of Omdurman in 1899.

Mahdist flags and jibbas were based on traditional clothes used by followers of Sufi religious groups in Sudan. As the Mahdist war went on, these textiles became more standard. They were color-coded to show military rank and different units.

Mahdist Flags

Sufi flags usually have the Muslim shahada (a declaration of faith). They also have the name of the group's founder. The Mahdi changed this flag style for military use. He added a quote from the Koran and a strong statement: "Muḥammad al-Mahdī is the successor of Allah’s messenger."

After Khartoum fell, a "Tailor of Flags" was set up in Omdurman. Flags were made in a standard way. Rules were set for the color and words on the flags. As the Mahdist forces became more organized, the word "flag" (rayya) came to mean a group of soldiers or a unit under a commander. The flags were color-coded to show the three main parts of the Mahdist army: the Black, Green, and Red Banners.

The Mahdist Jibba

The patched muraqqa'a, and later the jibba, was a traditional garment. It was worn by followers of Sufi religious groups. This patched garment showed that the wearer rejected material wealth. It showed a commitment to a religious life. Muhammad Ahmad al-Mahdi ordered all his soldiers to wear this garment in battle.

Wearing this religious garment as military uniform helped unite his forces. It removed old visual differences between tribes that might have fought each other. During the war, the Mahdist military jibba became more styled. Patches were color-coded to show the wearer's rank and military unit.

See also

In Spanish: Guerra mahdista para niños

In Spanish: Guerra mahdista para niños

- History of Sudan (1884-1898)

- Northern Africa Railroad Development

- List of journalists killed during the Sudan campaign

- Category:People of the Mahdist War

- Millennarianism in colonial societies

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |