Jibba facts for kids

The jibba (say JOO-bah) is a long coat, like a cloak, often worn by Muslim men. This article tells you about a special kind of jibba. It became famous in Sudan in the late 1800s.

Back then, a man named Muhammad Ahmad announced he was the Mahdī. In some Islamic beliefs, the Mahdī is a special leader. He is expected to come and make the world fair. Muhammad Ahmad's followers were called the Anṣār, which means 'helpers'.

The Mahdī asked his followers to join a struggle, or jihad. This was against the government ruling Sudan, which was led by Turkish and Egyptian rulers. He told all his Anṣār to wear a special patched jibba. This was more than just a coat; it was a powerful symbol. It showed they were dedicated to a simple, religious life. They were ready to follow the Mahdī. The patches were like those on clothes worn by Sufi religious people. This showed they didn't care about fancy or worldly things. Mahdists believed wearing the jibba helped bring back what they saw as true Islamic ways to Sudan.

Contents

Why the Jibba Was So Important

The Jibba's Religious History

The idea for the Mahdist jibba came from a special robe called a muraqqa’a. This was a patchwork robe worn by Sufis. Sufis follow a spiritual path in Islam. They often choose to live very simple lives.

Wearing a muraqqa’a was a great honor, not a sign of poverty. A Sufi student usually got one after many years of learning. Their teacher would give it to them when they were ready to live a life of asceticism. This means a simple life focused on spiritual things, not on owning many things.

If these special robes got torn, they were not thrown away. Instead, they were carefully mended with new patches. This showed humility and a focus on spiritual matters. Muhammad Ahmad, the Mahdī, received a patched robe like this. He got it when he finished his Sufi training in 1868. Later, in 1881, when he declared himself the Mahdī, he ordered all his followers, the Anṣār, to wear a similar patched jibba.

How the Jibba Became a Uniform

The Mahdī's followers had two main goals. They wanted to turn away from worldly, fancy things. They also wanted to be dedicated to the jihad (holy struggle) the Mahdī had announced. The jibba's design showed both of these important values.

The patches on the jibba clearly showed their religious dedication. As the war continued, the patches also started to show a soldier's military rank. They also showed which group they belonged to.

Making everyone wear the jibba was a very smart idea. In Sudan, different tribes traditionally wore their own distinct clothes. By having everyone wear the same jibba, it helped unite all the different groups fighting for the Mahdī. It made them feel like one strong, unified force.

Over time, the Mahdist jibba changed. It became less like the randomly patched Sufi robe. It became more like a proper uniform:

- It was designed to be more symmetrical (balanced on both sides) and stylish.

- Two main types of jibba appeared:

- Ordinary soldiers wore simpler jibbas. Their patches were usually only red and blue.

- Military leaders wore fancier jibbas. These were often more detailed, made with brighter colors. They might have a special scrolled patch or pocket on the chest. Embroidery was also used to highlight the neckline. The bright colors and detailed designs of these leaders' jibbas made them easier to see during battles.

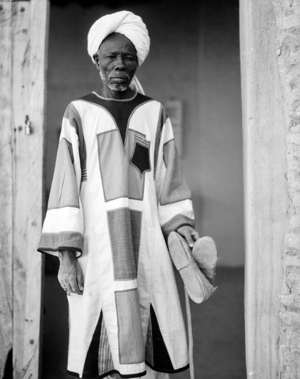

Even after the Mahdist state ended, some Mahdists kept wearing the leader-style jibbas. They wore them for important formal events. The picture here shows a caretaker at the Khalifa House Museum in Omdurman wearing one of these jibbas in 1936.

How Jibbas Were Made

The original Sufi robes, the muraqqa’a, were usually made from wool. Some people even think the word "Sufi" comes from suf, which is the Arabic word for wool. However, the jibbas worn by the Mahdī's followers were made from a rough type of cotton fabric called dammur.

The job of making these jibbas was mostly done by the women of the Mahdist community. The women would:

- Spin cotton threads.

- Weave these threads into fabric using machines called looms.

- Cut and sew the fabric to create the jibba's shape. Jibbas often had a flared (wide at the bottom) skirt and long sleeves.

- Finally, they would sew on the patches. This technique of sewing fabric shapes onto another piece of fabric is called appliqué.

The patches were also usually made of cotton. But sometimes, other materials were used. For example, after the Mahdists won an important battle at the Siege of Khartoum, they found supplies of wool in the city. Much of this wool was then used to make and repair patches on the jibbas. They even used scraps of enemy uniforms found on battlefields to patch their clothes! Most of the production was done by women. But European prisoners were sometimes involved in making the jibbas too.

In a museum in Paris, France (the Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac), there is a jibba with red and black embroidered patches. It even has a message written under the armpits. It says, "This tunic should be put on with pride and wisdom."

Clothes as Messages: A Failed Peace Attempt

Clothes were not just for wearing or for identifying soldiers. They also played a role in diplomacy (communication between leaders) during the Mahdist War. However, these attempts were not successful. The Mahdī and the Governor-General of Sudan, an Englishman named Charles George Gordon, actually sent gifts of clothing to each other. They both hoped this gesture might make their opponent stop fighting.

Gordon sent the Mahdī a Turkish fez (a type of brimless hat) and a rich, red robe of honor. These were meant as respectful gifts. But the Mahdī did not see it that way. He believed in asceticism (a simple life without luxuries). So, he thought these fancy clothes were an insult to his values. In return, the Mahdī sent Gordon a simple, patched jibba. It was made from homespun fabric. He explained that this was 'the clothing we want for Ourself and Our Companions who desire the world to come'. This meant those who focus on the afterlife. The Mahdī hoped Gordon would wear the jibba and maybe even convert to Islam. Sadly, this exchange of clothing did not lead to peace between the two sides.

Jibbas as War Trophies

The Mahdist State was set up in Sudan in 1885. This happened after the Mahdists won the Siege of Khartoum. Sadly, the Mahdī died shortly after this victory. He was succeeded by Khalifa Abdulahi, who continued to rule the Mahdist state. The Mahdist state, also known as the Mahdiyya, lasted until 1898. In that year, an Anglo-Egyptian army (soldiers from Britain and Egypt) won a big victory. This army was led by Lord Kitchener. They defeated the Mahdist forces at the Battle of Omdurman.

After this battle and other Anglo-Egyptian victories, like those at 'Aṭbara and Tūshka, many jibbas were collected from the battlefields. These garments were taken to Britain as war trophies. Trophies are items taken to show victory. Today, many of these historic jibbas are kept in museums and cultural places across the United Kingdom. Rudolf Carl von Slatin, an Austrian, had been a prisoner of the Mahdist forces. He was freed in 1895. He was later photographed dressed as an Anṣār soldier, wearing a patched jibba. The jibba he wore in the photo might have been one taken from a recent battlefield.

Where Did "Jibba" Come From?

The Arabic word jubbā is believed to be the origin of the word "jibba." This Arabic word is also thought to be the source of similar words in other languages:

- In Italian, the word giubba can mean a type of skirt or jacket.

- In French, the word jupe means a skirt.

- In modern English, jupes is an old word, mainly used in Scotland. It means a man's coat, jacket, or tunic.

Going back to the late 1200s, the word "jupe" in Old French meant a man's loose jacket. This type of jacket was often worn under armor for extra protection. So, the idea of a "jibba" or "jupe" as an outer garment has a long history!

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |