Charles George Gordon facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Charles George Gordon

|

|

|---|---|

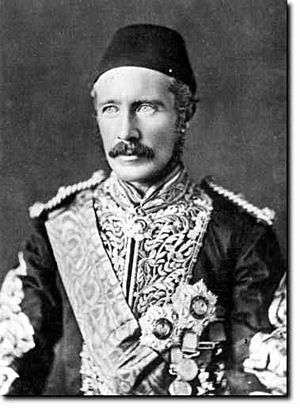

Gordon between 1878 and 1885

|

|

| Nickname(s) | Chinese Gordon, Gordon Pasha, Gordon of Khartoum |

| Born | 28 January 1833 Woolwich, Kent, England |

| Died | 26 January 1885 (aged 51) Khartoum, Mahdist Sudan |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1852–1885 |

| Rank | Major-General |

| Commands held |

|

| Battles/wars |

|

| Awards |

|

| Signature | |

Major-General Charles George Gordon (28 January 1833 – 26 January 1885) was a famous British Army officer and administrator. People knew him by many names, like Chinese Gordon, Gordon Pasha, and Gordon of Khartoum. He fought in the Crimean War and became very well-known for his work in China. There, he led a group of Chinese soldiers called the "Ever Victorious Army" and helped stop the Taiping Rebellion. Because of his success, he received special honors from both the Chinese Emperor and the British.

Later, Gordon worked for the leader of Egypt, called the Khedive. He became the Governor-General of the Sudan. In this role, he worked hard to stop local rebellions and the slave trade. He left in 1880, but a big revolt soon started in Sudan, led by a religious leader named Muhammad Ahmad, who called himself the Mahdi.

In 1884, Gordon was sent back to Khartoum to help evacuate soldiers and civilians. But he decided to stay and defend the city. He organized a strong defense that lasted almost a year. This made him a hero to the British public. However, the government wanted him to leave. A relief force was sent, but it arrived two days after Khartoum fell and Gordon was killed.

Contents

- Early Life and Military Beginnings

- Fighting in the Crimea

- Adventures in China

- Life in Gravesend

- Service in Egypt and Sudan

- Governor-General of Sudan

- New Opportunities and Return to China

- The Mahdist Uprising in Sudan

- Defending Khartoum

- The Siege of Khartoum

- The Fall of Khartoum and Gordon's Death

- Memorials and Legacy

- See also

Early Life and Military Beginnings

Charles George Gordon was born in Woolwich, Kent, England. His father was also a Major General in the British Army. The men in Gordon's family had been army officers for four generations. It was expected that Charles would follow in their footsteps. All his brothers also became officers.

Gordon moved around a lot as a child because of his father's army postings. He went to schools in England and the Ionian Islands. When he was 10, his sister Emily died, which greatly affected him. His older sister, Augusta, who was very religious, helped him find comfort in faith.

As a young army cadet, Gordon was known for being lively and sometimes rebellious. He didn't like rules he thought were unfair. This even delayed his graduation by two years. However, he was very good at making maps and designing forts. This led him to join the Royal Engineers, also known as "sappers." Sappers were elite soldiers who did dangerous jobs like scouting and building defenses.

Gordon became a second lieutenant in 1852 and a full lieutenant in 1854. He was a natural leader and could inspire his men. But his superiors sometimes found him difficult because he would disobey orders if he thought they were wrong.

His first job was building forts in Milford Haven, Wales. Here, he met friends who introduced him to a strong Christian faith. He often quoted a Bible verse: "For to me, to live is Christ, and to die is gain." Gordon was very religious but did not belong to any single church. He believed all churches were like different "regiments" in one army.

Fighting in the Crimea

When the Crimean War began, Gordon was sent to the Russian Empire in January 1855. He was eager to fight against Russia, which was Britain's main enemy at the time. He worked on mapping Russian forts during the Siege of Sevastopol. This was a very dangerous job, and he was wounded for the first time.

Gordon spent over a month in the trenches around Sevastopol. He became known as a brave and skilled officer. People at the British headquarters would say, "If you want to know what the Russians are up to, send for Charlie Gordon." He also took part in the expedition to Kinburn.

After the war, he helped mark the new border between the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire. He traveled through Moldavia (modern Romania) and Armenia, taking many photographs. He was a keen amateur photographer and was honored for his Armenian photos. Gordon returned to Britain in 1858 and became an instructor. He was promoted to captain in 1859.

Adventures in China

Gordon found his work in Britain boring and wanted to be sent where there was action. In 1860, he volunteered to go to China during the Second Opium War. He arrived too late for the main fighting but soon learned about the Taiping Rebellion.

At first, Gordon felt some sympathy for the Taiping rebels, who claimed to be Christians. But after seeing the terrible things they did to local people, he wanted to stop them. He called their army "cruel" and "desolating." He was present when the Old Summer Palace was destroyed. He thought it was "vandal-like" but understood why it happened after Chinese officials killed British and French officers.

British and French forces stayed in northern China to protect European settlements from the Taiping army. Gordon joined their staff as an engineer. They worked with an American-led force to clear rebels from around Shanghai.

The American commander, Frederick Townsend Ward, was killed. His replacement was not liked by the Chinese authorities. So, Li Hongzhang, a Chinese governor, asked for a British officer to lead the force. He chose Gordon, who was known for being honest and fair. Gordon made sure his soldiers were paid on time, which was unusual for the time. He also designed their uniforms.

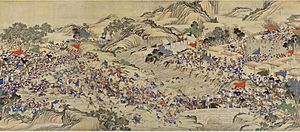

In March 1863, Gordon took command of the force, which was named the "Ever Victorious Army". He quickly led them to help the town of Changsu and earned his troops' respect. Gordon treated prisoners well, which encouraged more Taiping rebels to surrender and even join his army. He also used China's network of canals and rivers to move his troops and supplies, which was a smart new idea.

Gordon preferred to outsmart the enemy rather than attack them head-on, which saved many lives. In May 1863, he used an armored paddle steamer, the Hyson, to break through Taiping defenses. This surprise attack caused the rebels to panic and flee. Local peasants, who had suffered under the Taipings, often attacked the fleeing rebels. Gordon was seen as a hero by the ordinary Chinese people.

Gordon had to keep strict control over his mercenary army, who were often interested in looting. He punished soldiers who stole from civilians. He also defeated another American mercenary who had joined the Taipings.

As he traveled, Gordon was shocked by the poverty and suffering he saw. This strengthened his religious faith, as he believed God would one day end such misery. Gordon was famous for leading battles with only a rattan cane, refusing to carry a gun or sword. His bravery and victories made many Chinese believe he had special powers.

In November, Gordon's forces helped capture the city of Suzhou. Gordon promised that any Taiping rebels who surrendered would be treated kindly. However, the Imperial Chinese forces executed all the Taiping prisoners, which made Gordon furious. He felt his honor was stained and believed it was a "stupid" act that would make other rebels fight to the death.

The Chinese Emperor offered Gordon a huge sum of money and high honors. But Gordon refused the money because of the massacre at Suzhou. He wrote that he was happy to leave China as poor as he came, knowing he had saved many lives. He was promoted to lieutenant-colonel in the British Army and received the Companion of the Order of the Bath.

Gordon's military career in China was very successful. He won 33 battles in a row. He returned to Britain in June 1864. His actions in China made him famous in Britain, and he earned the nickname "Chinese" Gordon.

Life in Gravesend

After China, Gordon returned to Britain and worked on building forts for the defense of the River Thames near Gravesend. He didn't like the forts, thinking they were useless and expensive.

Gordon also spent a lot of time helping homeless boys in Gravesend. He called them "scuttlers" and often let them stay in his home, Fort House. He and his housekeeper set up classrooms for them. He also rented a small house where working boys could learn for free. Gordon was very generous, giving away about 90% of his yearly income to charity.

His friends said his time in Gravesend was the "most peaceful and happy of his life." But Gordon often felt bored and kept asking the War Office for dangerous assignments.

Service in Egypt and Sudan

In 1871, Gordon worked on a commission to maintain navigation on the River Danube. He found the work boring and spent time exploring Romania. He even helped rescue a girl who had been abducted.

In 1872, he was promoted to colonel. He then met the Prime Minister of Egypt, who offered him a job working for the Egyptian leader, Isma'il Pasha. Gordon accepted with the British government's approval and went to Egypt in 1874. Isma'il Pasha was known for spending a lot of money and wanted to make Egypt more like Europe. He was surprised when Gordon refused a very high salary, saying £2,000 a year was enough.

Isma'il Pasha wanted to expand Egypt's empire in Africa. He hired many Westerners to help, including Gordon. Gordon was asked to be the governor of Equatoria province, which is now parts of South Sudan and northern Uganda.

Gordon's main goal in Equatoria was to stop the slave trade. This was a huge challenge because many Egyptian officials were involved in the trade and tried to stop his efforts. Gordon found the Egyptian system of rule unfair and cruel. He wanted to help the local African people, who had suffered greatly from slave traders. He often said, "I taught the natives they had a right to exist."

He worked hard to explore the area and set up stations to fight slavery. He also had to deal with diseases like malaria. Gordon traveled through thick jungles and ravines, exploring Lake Albert and the Victorian Nile. He also acted as a diplomat, dealing with local kings like Muteesa I of Buganda.

Gordon often personally stopped slave convoys and freed the slaves. However, he found that corrupt officials often sold the freed Africans back into slavery. Despite the difficulties, Gordon wrote that he liked the work. His efforts to end slavery made him very popular in Britain.

Gordon clashed with the Egyptian governor of Khartoum over slavery. He eventually left Sudan for London. But the Khedive asked him to return, this time as Governor-General of the entire Sudan. Gordon accepted and was given the title of pasha.

Governor-General of Sudan

As Governor-General, Gordon faced many challenges. He tried to end slavery and stop cruel practices like torture and public floggings. He was known for being very stubborn, joking that he was like a camel with an idea in its head. He wanted to change the system to benefit the people, but many officials were corrupt and ignored his orders.

Gordon traveled constantly across Sudan to make sure his orders were followed. He became very popular with ordinary Sudanese people. They would cheer for him when he arrived.

In the 1870s, efforts to stop the slave trade caused economic problems in northern Sudan, leading to unrest. Egypt also went bankrupt in 1876, which meant there was no money for Gordon's reforms. Gordon tried to convince European financial leaders to help, but they were not interested in his plans.

Slavery was central to Sudan's economy. Gordon had to confront powerful slave traders like Rahama Zobeir. When a rebellion broke out in Darfur, Gordon rode into the rebel camp unarmed to negotiate. He promised jobs to those who surrendered. This brave move worked, and many chiefs pledged loyalty.

Later, Zobeir's son rebelled again. Gordon and his friend Romolo Gessi pursued him. Gessi eventually captured and executed Zobeir's son, as he had broken his promise.

Gordon tried another peace mission to Abyssinia (modern Ethiopia) but was imprisoned for a short time. He then returned to Cairo and resigned from his Sudan job. He was exhausted. Gordon had hoped to change the unfair system in Sudan, but he felt he had failed. The corruption and greed of others had defeated his efforts.

After his resignation, Gordon traveled to Switzerland. He had a religious experience there, which deepened his faith. He believed in reincarnation and thought the Garden of Eden was in the Seychelles islands. Gordon was very religious and gave a lot of money to charity.

New Opportunities and Return to China

In 1880, King Leopold II of Belgium asked Gordon to lead the Congo Free State. Gordon refused, partly because he still cared about Sudan and disliked working for a private company. He also turned down a job in South Africa.

Then, he was invited back to China because there was a risk of war between China and Russia. Gordon felt a strong connection to China and wanted to help. He even said he would give up his British citizenship to fight for China if war broke out.

Gordon went to Beijing and tried to convince Chinese leaders to seek peace. He warned them that Russia's navy was powerful. He even bluntly told them they were being "idiotic" for not compromising. He also advised them to treat the Han Chinese majority better. His directness led to him being ordered out of the court, but he stayed in Tianjin.

Gordon's old friend, Sir Robert Hart, described him as "very eccentric" and "spending hours in prayer." He believed Gordon was "unbalanced" and thought all his ideas came from God. The British government ordered Gordon home, not wanting him to fight for China against Russia.

Back in Britain, Gordon visited Ireland and was shocked by the poverty of Irish farmers. He wrote to Prime Minister Gladstone, urging land reforms to help them. He compared it to ending slavery.

In 1881, Gordon went to Mauritius as Commander of the Royal Engineers. He found the work boring. He visited the Seychelles islands and believed they were the location of the Garden of Eden. He was promoted to major-general in 1882.

Gordon then spent a year in Palestine, exploring biblical sites. He lived with an American family in Jerusalem and suggested a different location for Golgotha, where Jesus was crucified. This site is now known as "The Garden Tomb" or "Gordon's Calvary."

The Mahdist Uprising in Sudan

King Leopold II again asked Gordon to lead the Congo Free State, and Gordon accepted. But soon after, the British government asked him to go back to Sudan. The situation there had become very bad. A new revolt had started, led by Muhammad Ahmad, the self-proclaimed Mahdi. The Mahdi was a religious leader who claimed to be a messianic figure in Islam. He declared a holy war against the Egyptian government, promising to create a new Islamic state.

The Sudanese people were tired of Egyptian rule and high taxes. Many joined the Mahdi's forces. In 1882, Britain took control of Egypt, so they also inherited the problems in Sudan.

Egyptian forces in Sudan were weak. In November 1883, the Mahdi's followers, called the Ansar, destroyed an Egyptian army of 8,000 soldiers. This victory greatly boosted the Mahdi's power. By the end of 1883, Egypt only controlled a few areas in northern Sudan.

The British Prime Minister, William Ewart Gladstone, decided that Britain should leave Sudan. But evacuating thousands of Egyptian soldiers and civilians was difficult.

In early 1884, Gordon was sent to Khartoum. His official orders were to report on the situation and advise on how to evacuate everyone safely. However, Gordon had other ideas. He gave an interview to a newspaper, The Pall Mall Gazette, where he criticized the government's plan to leave Sudan. This caused a public outcry, and many people demanded that Gordon be sent to defeat the Mahdi.

Gordon was a good friend of Garnet Wolseley, a powerful general who wanted Britain to stay in Sudan. Wolseley used the media to pressure the government to send Gordon. On January 16, 1884, the government reluctantly sent Gordon to Sudan.

Gordon arrived in Khartoum on February 18. He was appointed Governor-General with full powers by the Egyptian leader. He immediately started sending out messages, attacking the rebels and saying he would "smash up the Mahdi." He also sent a telegram to Khartoum saying, "Don't be panic-stricken. Ye are men, not women. I am coming. Gordon."

Gordon made a big mistake by telling local tribal leaders that the Egyptians were leaving. This caused many Arab tribes to join the Mahdi. He also tried to negotiate with the Mahdi, offering him a position as a provincial governor. The Mahdi refused, demanding Gordon convert to Islam.

Gordon's actions were often unpredictable. He even suggested that his former enemy, the slave trader Rahama Zobeir, be made the new Sultan of Sudan. This shocked Gladstone and Gordon's supporters in the Anti-Slavery Society.

Defending Khartoum

After arriving in Khartoum, Gordon decided he would not evacuate the city. He announced he would hold Khartoum against the Mahdi. A crowd of 9,000 people welcomed him, chanting "Father!" and "Sultan!" Gordon promised them he would stop the Mahdi.

He began evacuating women, children, and the sick. About 2,500 people left before the Mahdi's forces surrounded the city. Gordon made his personal messages to London public to gain support for his plan. He even suggested bribing the Ottoman Sultan to send troops.

The rebels also attacked in eastern Sudan. British forces had to be sent to fight them. Gordon urged that a road from Suakin to Berber be opened, but his request was refused. In April, the British forces withdrew, leaving Khartoum completely isolated.

Gordon decided to stay and defend Khartoum despite government orders. He wrote in his diary that he was "very insubordinate" but couldn't help it. The government was angry but couldn't fire him because of public support.

Gordon had a strong desire to die fighting. He wrote that he wanted "release" from life. He saw himself as a Christian hero fighting against the Mahdi. He worked tirelessly to turn Khartoum into a fortress. He even put guns on paddle steamers to create his own navy.

Gordon had a low opinion of most of his Egyptian and Turkish troops, calling them "mutinous." But he praised his Black Sudanese soldiers, many of whom were former slaves. They fought bravely, knowing the Mahdi's forces would enslave them again.

The Siege of Khartoum

The siege of Khartoum began on March 18, 1884. At first, it was more of a blockade. Gordon's armored steamers could still get in and out. The British public demanded a relief expedition. Gordon sent defiant telegrams, saying he would hold out and that abandoning the garrisons would be an "indelible disgrace."

Gladstone opposed sending a relief force, calling it a "war of conquest against a people struggling to be free." But public pressure grew. On July 25, the Cabinet voted to send a relief expedition.

Gordon kept a diary during the siege, writing about his thoughts and faith. He led a strong defense, sending out his steamers and making raids on the enemy. He even had a military band play concerts to keep morale high. He built his own telegraph network within the city and used primitive landmines.

The British relief force, led by Gordon's old friend Garnet Wolseley, was not ready until November 1884. Wolseley was slow and cautious, which delayed the expedition.

On September 4, Gordon's forces suffered a major loss when about 1,000 of his best troops were killed in an ambush. On September 9, an armored steamer carrying Gordon's chief of staff and a journalist was captured. Gordon's cipher key was also taken, making it harder for him to communicate.

The British press portrayed Gordon as a saintly Christian hero fighting evil. His defenses were strong, but the Mahdi's artillery slowly broke them down. By the end of 1884, the people of Khartoum were starving. Gordon allowed civilians to leave if they wished, and about half the population left.

Gordon sent a message to Wolseley on December 14, saying, "Khartoum all right. Can hold out for years." But the messenger also carried a secret message: "We want you to come quickly." The Mahdi offered Gordon safe passage out of Khartoum, but Gordon refused.

Gordon and the Mahdi never met, but they respected each other as religious soldiers. Gordon's diary showed the stress of the siege. He swung between wanting to die a martyr and fearing his end. He wrote that he would not obey orders to leave Khartoum.

On January 5, 1885, the Ansar took a fort that allowed them to fire directly on Khartoum's defenses. In his last weeks, Gordon was described as desperate and chain-smoking. He would pace the palace roof, looking for the relief steamers.

The Fall of Khartoum and Gordon's Death

The relief force was still far away. On January 24, two of Gordon's gunboats, carrying a small reconnaissance party, were sent to Khartoum. They were not meant to rescue Gordon or bring supplies.

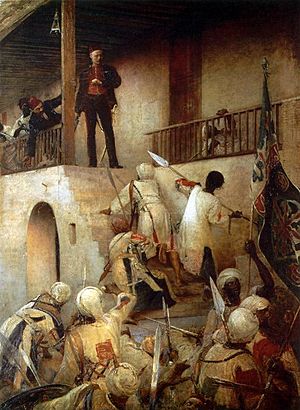

At dawn on January 26, 1885, the Ansar launched their final attack. They stormed the city through a gap in the defenses caused by the low Nile River. After an hour of fighting, the starving defenders gave up. The city fell, and about 7,000 defenders were killed.

When the reconnaissance gunboats arrived on January 28, they found Khartoum had fallen and Gordon had been killed two days earlier.

The exact way Gordon died is not certain. A popular story says he went out unarmed, wearing his ceremonial uniform, and was cut down by the Ansar. This story made him seem like a Christ-like figure. However, his servants later said he fought with a loaded revolver and a sword. He was likely shot and then speared. His body was not found.

News of Gordon's death caused huge sadness in Britain. Queen Victoria sent a strong message to Prime Minister Gladstone, blaming him. Critics called Gladstone the "Murderer of Gordon." People threw stones at 10 Downing Street, Gladstone's home. Gordon was seen as a saintly Christian hero who died resisting the advance of Islam.

Despite calls to "avenge Gordon," the British government did not immediately conquer Sudan. It was too expensive. However, in 1898, a British force under Herbert Kitchener conquered the Mahdi's state. This was mainly to stop the French from taking control of Sudan. But the British public and Kitchener himself saw it as avenging Gordon. Kitchener even blew up the Mahdi's tomb as revenge.

Memorials and Legacy

Many memorials were built for Gordon across Britain and the world. Statues were put up in London, Chatham, Gravesend, and Melbourne, Australia. A school, Gordon's School, was also founded in his memory. The Gordon Hospital in London was renamed in his honor.

Gordon's memory lived on for a long time. Early books about him praised him as a hero. However, later writers, like Lytton Strachey, criticized him, calling him a "deranged egomaniac." But even then, many still admired him.

Some historians now believe Gordon had a "death wish" and that his bravery in battle was partly due to this. However, this is still debated.

Gordon also left a legacy in China and Sudan. In China, his role in stopping the Taiping Rebellion is now seen differently. The Taipings are sometimes viewed as early communists, so Gordon's actions against them are less celebrated. No monuments to him exist in China today.

In Sudan, historians focus more on the Mahdi's rebellion. Gordon is mainly seen as the enemy general at Khartoum, and his work against slavery is often overlooked.

In 1982, a documentary about Gordon's life was made, called "Gordon of Khartoum."

See also

In Spanish: Charles George Gordon para niños

In Spanish: Charles George Gordon para niños